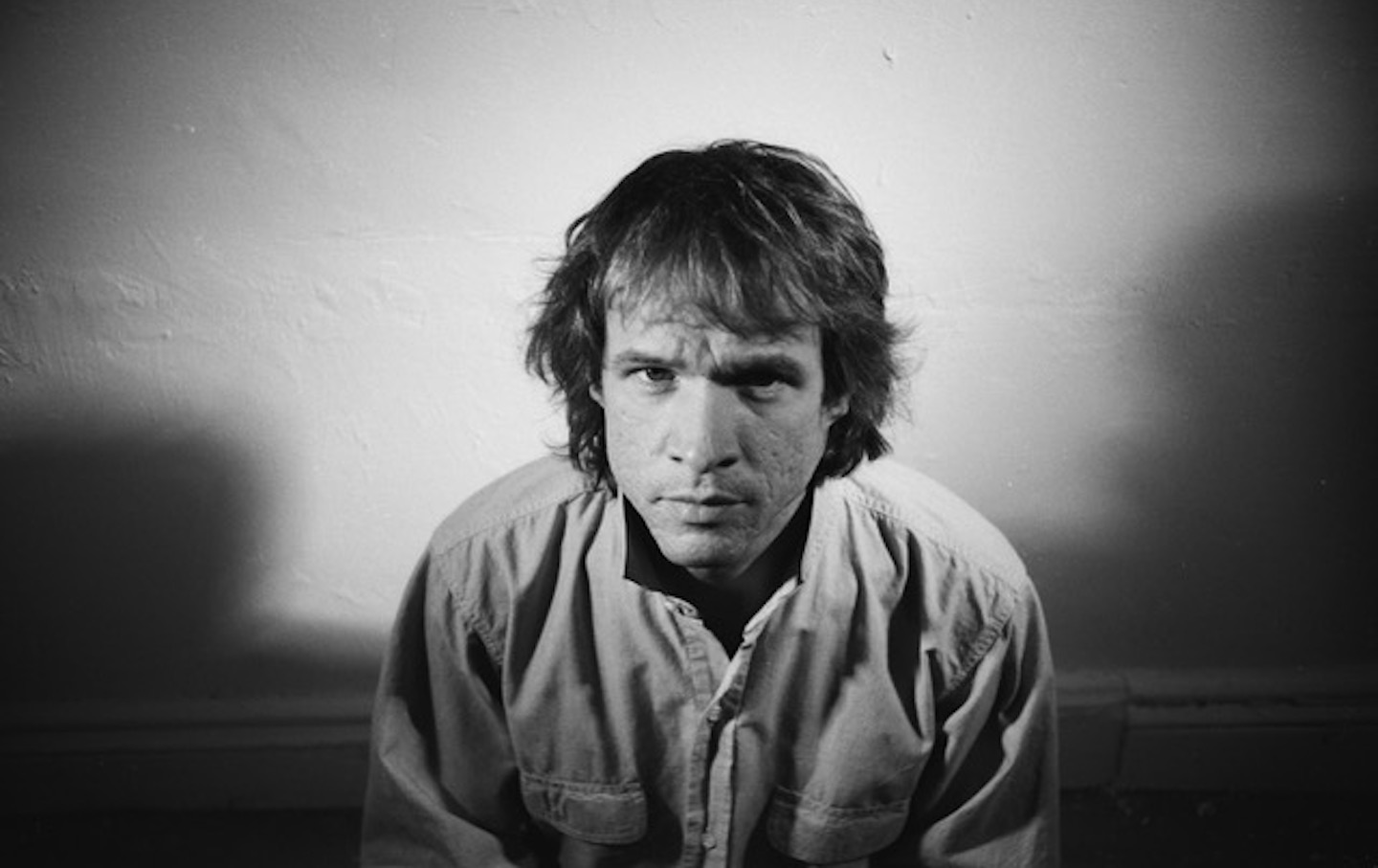

Arthur Russell. (Photo by Tom Lee / Courtesy of Audika Records)

There’s no knowing what the late composer, singer, and multi-instrumentalist Arthur Russell had in mind when he recorded the composition he titled “Picture of a Bunny Rabbit,” an eight-minute piece for electric cello that serves as the title track on the latest collection of his previously unreleased recordings. Still, the songs made me think of something Pete Seeger once said: “The truth is a rabbit in a bramble patch. All you can do is circle around saying, ‘It’s somewhere in there,’ as you point in different directions. But you can’t put your hands on its pulsing, furry little body.” The principle of unknowability that Seeger captured in his folksy parable certainly applies to the elusive work on the new album and, more broadly, to the whole of Russell’s music. Ephemeral, unpredictable, voluminous and yet incomplete, much of it unresolved and perhaps irresolvable, it’s a body of pulsing, furry music, the true nature of which can be awfully hard to grasp.

At the time of his death from AIDS in 1992, at the age of 40, Russell had released only a small portion of the recordings he had been working on compulsively over the last two decades of his life. Since then, awareness of the scale, the variety, the uniqueness, and the extraordinary high quality of his output has been growing steadily, thanks to the ardent stewardship of his recording archive by Steve Knutson, a savvy music-business veteran long associated with the dance and hip-hop label Tommy Boy Records. Working in cooperation with Tom Lee, Russell’s partner during the time of his HIV diagnosis, illness, and death, Knutson founded a new label, Audika Records, devoted primarily to Russell’s legacy. Over the past two decades, Knutson and Lee have packaged 10 full-length albums of Russell’s material, much (though not all) of which had been unheard during the composer’s lifetime.

Picture of a Bunny Rabbit brings together nine pieces in varying stages of gestation, all of which come from the pool of recordings Russell drew from for World of Echo (1986/88), his second studio album and the only one released on a major label while he was alive. The discophile science of parsing such information is complicated and of interest mainly to collectors on the hunt for rarities like Tower of Meaning, the 1983 album of short orchestral pieces Russell composed for a Robert Wilson production of Medea, pressed for a limited release by Chatham Square, a label Philip Glass once owned. Or the 12-inch vinyl records of dance music Russell made for underground-club DJs in the early 1980s. (Russell and Wilson clashed during the rehearsals for Medea, and Russell’s music was dropped from the production.)

The pieces on Picture of a Bunny Rabbit are all works in progress. That is to say, they are exemplary specimens of Russell’s aesthetic in practice. In ways that connect his music to performance art, action painting, and jazz improvisation, Russell’s whole approach was a rejection of the static, finished product as an ideal in art, an argument against the very idea of finality. The process of making was what absorbed Russell, and that process was always ongoing.

Five of the tracks on Picture of a Bunny Rabbit are test pressings for an intended album of vague intentions, and they sound like experiments: On “In the Light of a Miracle,” a scratch-like rhythm pattern, processed with pre-digital electronics, sets up a groove over which Russell sings free-form chant-like phrases in a lovely, glistening tenor. While experimental, even provisional, in spirit, the music is wholly satisfying, a document of a seemingly miraculous moment that wouldn’t be improved by refinement: the spirit of the unaccountable, the light of a miracle.

We know from the version of World of Echo released in 1988 by Rough Trade that Russell chose not to include “In the Light of the Miracle” on it. And we know from the first collection of his unreleased material issued after his death, Another Thought, that he worked on the song again—and probably again and again—at one point creating a dreamy, dance-y version with hand drumming and a staccato melody performed on trombone. To take in two or three of the posthumous collections of Russell’s music is to encounter his ideas in perpetual flux. The same or similar lyrics pop up in different settings. “This Is How We Walk on the Moon,” an avant-garde chamber piece for voice and cello on Another Thought, turns up as a disco number with electric keyboards and drum machine on Corn. The core themes of “Treehouse” and “Keeping Up” reappear on different collections in variations—slowed down, sped up, repeated, extended, or rearranged.

This is partly a function of the fact that we’re hearing work tapes and demos, in many cases. Countless artists try out variations on themes in the workshop stage. Russell’s case is unusual, though, in that variation is a defining quality of his work. In its elemental contingency and provisionality, Russell’s music foreshadows the art experience of today: It’s unstable, like the music and streaming content that comes and goes all day, taking off on the stuff that preceded it as it sets up terms for the stuff to follow. Made in the cassette era, Russell’s music conjures the spirit of the digital age.

In the 2008 documentary Wild Combination: A Portrait of Arthur Russell, directed by Matt Wolf, there’s a shot of the box for a tape reel of demos that Russell had submitted to Warner Records. An A&R exec at the label scrawled on the top, “Who knows what this guy is up to—you figure it out.” As the resolutely varied contents of the many boxes of his tapes make clear, Russell seemed to know perfectly well what he was up to: He was tapping his impulses, which were polygenous, and giving them form through the act of experimentation.

“The things that I like seem to be so different—they’re not the things that everybody likes,” Russell explained in one of his few known interviews, a brief one for the Stony Brook University radio station in 1986.

Indeed, a key quality of Russell’s aesthetic that worked against him in his time but now makes him look prescient is the wide-ranging eclecticism of his music. After a youth steeped in classical music, playing cello and piano in his native Iowa, Russell joined a Buddhist commune in San Francisco and soaked in Tibetan spiritual music. He moved to New York in the early 1970s, an explosive time for the city’s divergent spheres of culture. Russell was attracted to them all and didn’t quite fit into any.

Picture of Bunny Rabbit by Arthur Russell

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

One of the posthumous Russell collections, Iowa Dream, shows him as an artful young singer-songwriter, accompanying himself on acoustic guitar and piano as he croons sensitive laments about the sound of dogs barking and his memories of the Iowa countryside. Several of the tracks were recorded with a pop-rock band Russell played in, the Flying Hearts, under the supervision of the renowned producer John Hammond, who planned to shop the tapes to record labels. According to Flying Hearts guitarist Larry Saltzman (quoted in Tim Lawrence’s 2009 biography, Hold On to Your Dreams: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973–1992), Hammond told Russell, “When they write my legacy, they’re going to say, ‘John Hammond discovered Billie Holiday, Charlie Christian, George Benson, and then Dylan, Springsteen, and Arthur Russell.’” It’s not clear why Hammond failed to launch Russell as he had promised, though the music on Iowa Dream would surely have puzzled a typical record executive of the ’70s: It is simultaneously quietly ruminative, buoyantly pop-ish, musically complex, catchy, and elegant—not quite at home in the Laurel Canyon world of confessional singer-songwriters, but hardly punk or New Wave.

Around the same time, Russell served for nearly a year as the music director of the Kitchen, a leading performance space for avant-garde music in downtown New York. He brought the Modern Lovers into the Kitchen and lost favor with the avant-gardists for disrupting the insular provincialism of the outré elite. He sat in with Talking Heads and played cello on an early recording of “Psycho Killer.” (I bought the 45 single at the time and still have my copy, though I had no idea who Russell was until years later.) He sang and played cello with Allen Ginsberg in concerts and on record. He loved disco and, working under a variety of names (including his own), produced or coproduced a string of spare and pulsing, proto-house records for the dance clubs that were the nexus of the erupting gay-consciousness movement: “Go Bang,” “I Need More,” “Is It All Over My Face,” “Pop Your Funk,” and more.

Singer-songwriter, pop-band leader, avant-gardist, disco prince… Arthur Russell was so many disparate, quasi-contradictory things that he never developed much of a following until the 2000s, when his blithe indifference to genre fell into sync with the times. Now, more than 30 years after his death, he seems trendy. His music, moreover, holds up astoundingly well. Its rhythmic core, contained in repeating electronic beats or funk patterns played on his cello as if it were an electric bass, has striking parallels in contemporary pop. His more intimate recordings of voice and cello songs, quiet and odd but unpretentiously blunt, sound like an adventurous current-day musician such as Mary Halvorson wrote them.

Other better-known artists are famous for having crossed genre barriers, of course. David Bowie made reinvention the very essence of his art, as Bob Dylan did before him and Bobby Darin did, too. All of them are duly celebrated as musical chameleons. Yet Arthur Russell stands apart—not above, but apart—because he was something other than a chameleon. He never altered his persona, his appearance, or his sensibility to make music so diverse, and he often combined elements of varying forms and genres freely, simultaneously, rather than hopping from one to another.

In a short video made for the release of Another Thought in 1994, David Byrne, Allen Ginsberg, and Philip Glass sat together to discuss Russell and his music. “He always felt that he could be a pop star—and that he should be one,” Glass noted. Decades ahead of his time, Russell was far from a pop star in his day. But the music of our own day, pop or otherwise, has a bit of Arthur Russell in it.

David HajduDavid Hajdu is the music critic of The Nation and a professor at Columbia University.