As the collections of Sir Moses Montefiore and David Solomon Sassoon go under the hammer today, what's the future for rare books and historic artifacts in the age of generative AI?

EDITOR’S NOTE:

Author’s Note: I wish to thank Shaul Seidler-Feller of Sotheby’s for the tour he gave of the exhibit that informed large parts of this article.

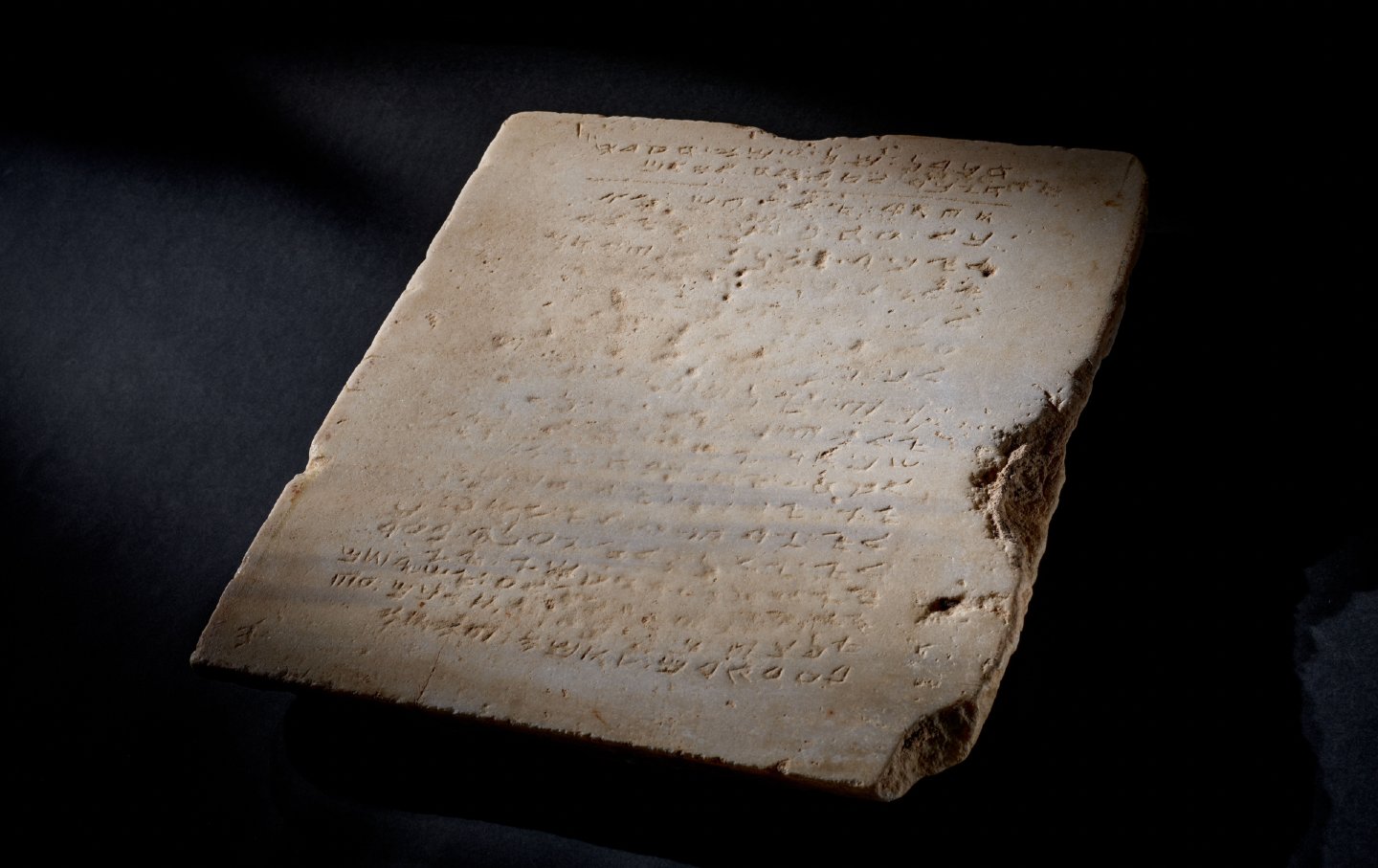

Fifteen hundred years ago, in the town of Yavne—famous as the site where Rabbinic Judaism was reborn in the aftermath of the destruction of the Second Temple—a group of Samaritans (descendants of the northern Kingdom of Israel conquered by the Assyrians over a millennium before) built a synagogue in which they inscribed a tablet with the Ten Commandments in the ancient Paleo-Hebrew script their community still used. Included in this list is the uniquely Samaritan 10th commandment (at the heart of the Jewish/Samaritan schism) to worship God on Mt. Gerizim, the mountain overlooking the city of Nablus in the West Bank—which was the city of Shechem in the ancient Kingdom of Israel, conquered by the Assyrians more than 2,700 years ago. The tablet would later be reused in a church and then a mosque that were built on the same site, before it was found in 1913 when work was being done on a now-defunct railroad connecting Egypt and the Ottoman Vilayet (province) of Syria.

On February 5, 1840, a little over two months before Passover, a Catholic friar and his Muslim servant went missing in Damascus—also in the Ottoman Vilayet of Syria. The Jews of Damascus were immediately suspected of having murdered them to collect their blood for the upcoming holiday in what marked a new export to the Middle East of the old Medieval Christian blood libel. Several Jews were rounded up and tortured so severely that two died, one converted to Islam to end the torture, and “confessions” were pried out of the rest. The situation became so dire for the Jewish community of Damascus that appeals were made to Jews throughout the world to plea their case. Sir Moses Montefiore (1784–1885) of London was arguably the most illustrious member of the Jewish delegation that came to their aid. He would go on to plead the cases of the Jews of Russia, Morocco, and Romania before his death at the age of 100.

David Solomon Sassoon (1880–1942) was the scion of the great Iraqi Jewish Sassoon family, originally from Baghdad. David was born in Bombay, India, where his family had migrated a couple generations before him. The Sassoon family would later move to London, where Moses Montefiore had lived, although not until shortly after he died.

David Sassoon and Moses Montefiore had more in common than just the fact that both lived in London. They were also both great bibliophiles, amassing two of the most important collections of Jewish manuscripts in the world. And both collections are currently on display along with the Samaritan tablet of the Ten Commandments at Sotheby’s, where they are being put up for auction today, December 18.

These two Londoners and their book collections embody much of the diversity that was the Jewish world of the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Montefiores were Sephardic Jews, hailing from Spain before the expulsion in 1492, but having remained in Europe. The Sassoons were Iraqi Jews, a community that traces its origins in Mesopotamia to the Babylonian conquest of the Kingdom of Judah 2,600 years ago. Their book collections overlap in ways that embody the vast shared heritage of Jews the world over—and also reflect the local customs and flavors of their respective Eastern and Western, Southern and Northern Jewish worlds.

The Sassoon collection is rich in Yemenite and Iraqi manuscripts. It includes a scroll of the opening chapter of the Book of Ezekiel with accompanying prayers to be read at the grave of the Prophet Ezekiel in a uniquely Iraqi Jewish rite. It also includes a 17th century Yemenite manuscript of the Pentateuch that contains floral patterns made from Hebrew verses, modeled after similar art from the Islamic world. Nothing could be more universally Jewish than the Pentateuch, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. Yet even here the book shows its uniquely Arabian influences in the way the scribe chose to decorate it. The scribe concluded the book with a colophon telling of the expulsion of the Jews of Yemen in 1679 to the desert where many of them died and where he made this copy. What more universal Jewish experience can one have than taking the Torah into exile on account of antisemitism? Yet how uniquely Yemenite was that experience of being sent off into the desert to starve?

Also in the collection is a 14th century copy of Maimonides’s Mishneh Torah (composed in late 12th century Egypt)— a religious law code studied throughout the Jewish world. And a copy of part of the Jewish legal code of Rabbi Isaac ben Jacob Alfasi (1013–1103), one of the first legal codes compiled from the Babylonian Talmud. The 16th-century Middle Eastern or North African manuscript preserves Alfasi’s more original version, before later changes set in as the text was copied in Europe.

The Montefiore collection includes a festival prayerbook (maḥzor) of the Romaniote Jewish community of Greece (specifically of Candia/Crete) who preceded the Jews who moved there from Spain after the expulsion of 1492, bringing with them their Spanish Jewish customs. A 14th-to-15th century prayerbook of the Western Ashkenazi type shows evidence of self-censorship to evade more significant Christian censorship. Like the Yemenite Pentateuch in the Sassoon collection, what more universal Jewish texts could we have than the prayerbook, the bulk of which is the same throughout the Jewish world, and at the same time, what more particular exemplars could we have than a rare Candia maḥzor or a prayerbook of the Western Ashkenazi tradition evincing the most European of Jewish experiences of self-censorship to avoid the Christian censors?

These manuscripts (and the Samaritan tablet) are invaluable as witnesses not only of the foundational Jewish/Samaritan texts which they comprise but also to the now-lost Jewish/Samaritan communities and worlds that produced them. The movement of the manuscripts of the Sassoon and Montefiore collections in many ways mirrors the movement of the communities that produced them as they were uprooted in the last century from their often millennium-old homes in Europe, Crete, Yemen, North Africa, and Mesopotamia, their surviving descendants having fled to the relatively safer havens of Israel/Palestine and the United States, the former where the current heir to the Sassoon collection now resides and the latter where the collection is being sold.

Yet book collections are so last century. The Jewish Theological Seminary of America in New York City recently downsized its library from what was the greatest Jewish library in the Western Hemisphere to a space not much larger than many New York apartments. Its sister school in Los Angeles, the American Jewish University, recently did the same. It is hard to even give away hard copies of books anymore. Digital books have replaced physical copies in the Jewish world no less than in the world at large. University libraries now have access to vast collections of digitized books and articles, and online collections of Jewish texts like Sefaria, Hebrewbooks.org, the Comprehensive Aramaic Lexicon, and alhatorah.org offer access to an enormous assemblage of ancient, medieval, and modern Jewish texts. Even access to high resolution scans of original Jewish manuscripts can now be had online through the Friedberg Geniza Project, the Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library, among a growing list of others.

On the one hand, the increasing availability of manuscripts online makes the physical copies less important, reducing them to collector’s trophies for the rich and famous. On the other hand, the increasing ability of generative AI to compose, edit, and doctor images makes the original physical copies all the more essential as the final arbiter of the primary sources of our collective historical past. Already we can foresee an all-too-real future when “deep fake” texts will attempt to rewrite our history, when doctored digital copies may claim to preserve the “original” version of a text. If digital copies are all we have, how will we manage to keep the record straight? These physical manuscripts should be treasured for the hard-and-fast record of our past that they embody.

Author’s Note: I wish to thank Shaul Seidler-Feller of Sotheby’s for the tour he gave of the exhibit that informed large parts of this article.

David BrodskyDavid Brodsky is the author of A Bride without a Blessing: A Study in the Redaction and Content of Massekhet Kallah and Its Gemara. He teaches in the Department of Judaic Studies at Brooklyn College.