The Bad Politics of Good Taste

Nathalie Olah’s exploration of the ethics of tastefulness dissects the class-bounded nature of most social and cultural mores.

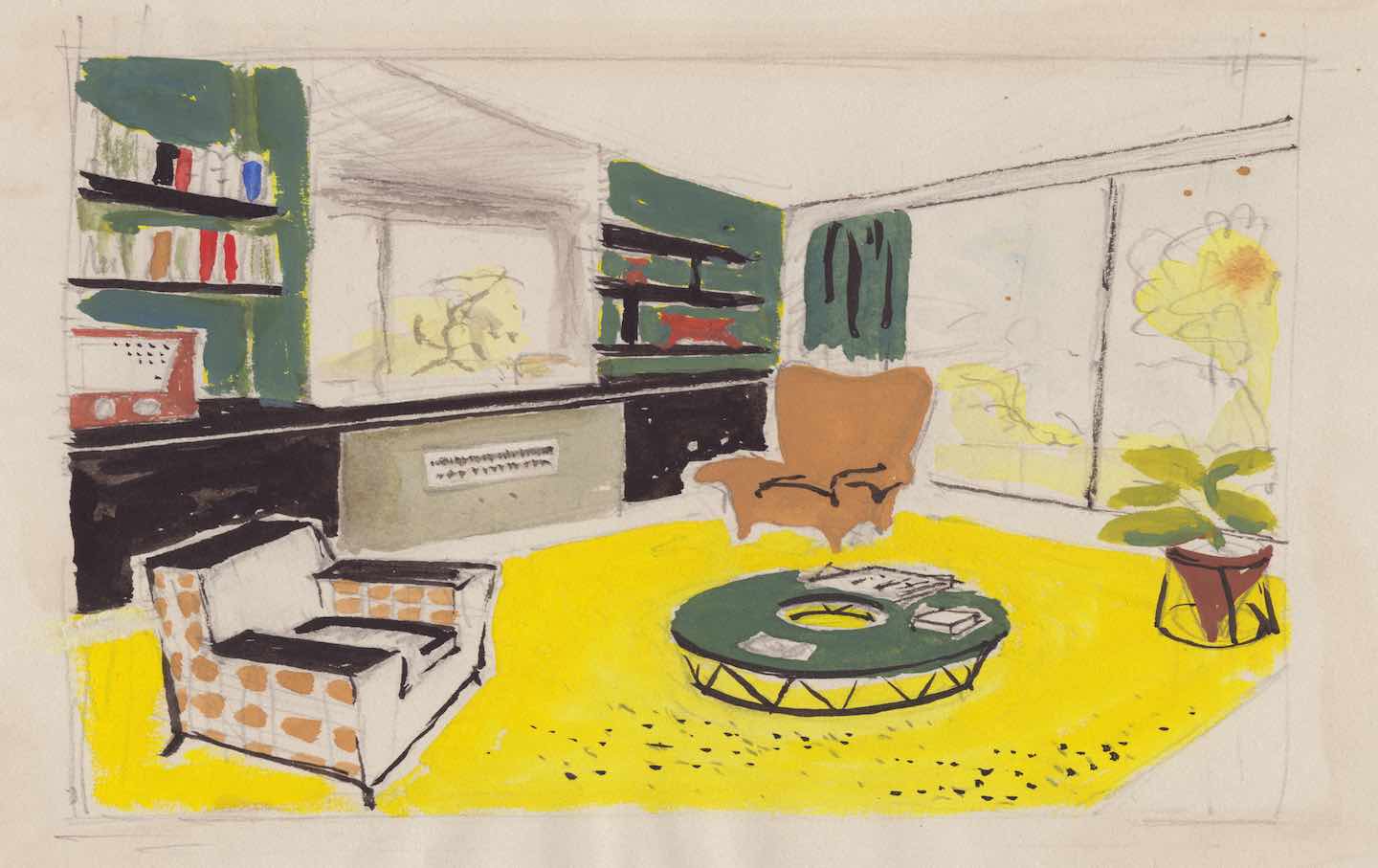

An illustration of interior design, 1951.

(Photo by Amanda Waite / Shirley Markham Collection / Heritage Images / Getty Images)The concept of “taste” is hollow and vain. Made up of rules, codes, and biases that reduce the complexity of preference and desire to the dichotomy of good or bad, the idea imposes a hierarchy of virtue based on consumer decisions and lifestyle choices. To make sense of such a precarious system—sustained by business interests and a desire for social status—seems futile. But taste determines how we live; it is our everyday—bound by class and power, and ripe for exploitation.

Books in review

Bad Taste: Or the Politics of Ugliness

Buy this bookIn Nathalie Olah’s Bad Taste: Or the Politics of Ugliness, the author sets out to examine taste as an expression of power, interrogating the brands, political leaders, celebrities, and cultural workers driving the capricious demands of aesthetic judgment. Taste is presented here as deliberate, a way to justify inequality. By normalizing harmful prejudices, certain regimes of taste benefit some and vilify others. Olah points, for example, to British Prime Minister David Cameron addressing an audience at a conference in 2006 to propose a crime-fighting approach based on instilling “good, honest” values in the homes of deprived children—who could often be seen in the streets wearing hoodies. “We, the people in suits, often see the hoodies as aggressive,” Cameron intoned before elaborating on his plan to bring a new social cohesion to Britain. For Cameron, the hoodie—worn by millions every day—conveyed a distance from the world of school and work, symbolizing menace and lawlessness instead. The popularity of hip-hop in the United States in the 1980s saw the hoodie adopted by the masses, but it is now an emblem of the prejudice and double standards that Black and brown people face daily: At the trial of George Zimmerman for the fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin in 2012, the testimony included mention of a hoodie that the American schoolboy was wearing.

A deeply researched work of cultural criticism, Olah’s book acts as a moving call to break free from the tyranny of the dominant taste. By the logic of such a tyranny, she notes, those with “good taste” are more deserving than those without. Olah proposes that we let go of these superficial judgments, and she compels us to ask: Who gains from conformity to such expectations? Recognizing that stepping outside of consumerism is a somewhat idealistic notion, at least in the short term, she suggests conceiving objects and experiences beyond what they signal socially. This will allay the restrictive forms of approval that we place on both ourselves and others, creating a more fulfilling way of navigating the world.

Bad Taste begins in the home, where a trendy emptiness has come to be regarded as virtuous. A life unencumbered by junk is the fantasy, held up by the authority of websites such as The Modern House—a British online lifestyle magazine founded in 2005—celebrating sparse, mid-century design. Its rise in popularity goes hand in hand with a generation of renters’ being forced into house shares by soaring prices and becoming overwhelmed with clutter. But the e-commerce site has contributed to the very problem from which people are trying to escape, Olah argues, hastening the perception of homes as objects of consumer desire rather than a human right.

Kinfolk, launched in 2011, upholds this style of sparsity. Usually found on coffee tables, the magazine valorizes handcrafted furnishings and espouses the idea that heirlooms, heritage, and tradition can be replicated in any home. Olah compares its ethos to Connaissance de la Campagne, a mid-century French interior and lifestyle guide that the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu argued “presupposes a culture, the privilege of those who have cultural roots,” noting that preserving lineage—whether tradition or knowledge—naturally favors the upper classes. Olah reasons that, in addition to being time-consuming to learn and follow, the rules of social mobility generally require working people to shun their backgrounds and family histories, leading to further division and ostracization.

A chapter on fashion interrogates how the perfect plain white T-shirt became a status symbol. Emphasizing “quality,” subdued, functional brands have exploited consumer anxiety—sustainable and ethical wear is available through mass modes of production—and profited significantly. First observed in the late 2000s, “normcore” is arguably one of the most enduring fashion trends of the century, replacing more overt expressions of style (generally inspired by films, music, and counterculture movements) with conformity. Popularized by influencers opening PR packages on YouTube, the style has reduced the billion-dollar fashion industry to its most basic form and created a new class of young professionals, changing workwear in the process. True frugality would require a change in economic conditions, not minor petty differences in threads: “Plain did not mean…easy and accessible,” Olah writes, “but that which carried a degree of design prestige.”

The commodification of free time, and the streamlining of both domestic and aesthetic concerns, involves denying the pressures of modern life altogether, begging the question of what it is we are trying to escape. No one has pushed this harder than British adventurer turned television personality Bear Grylls, preoccupied with survivalism and pushing himself to his limits. His impact is substantial: In 2015, former US president Barack Obama appeared on the NBC show Running Wild With Bear Grylls keen to test and display his strength of character and fitness. (Some 3.5 million viewers watched the episode live.) The same year, Grylls released a line of survival tools via Walmart. The show has since been criticized after evidence emerged that Grylls occasionally sleeps in a nearby hotel and is given food by the show’s crew. Olah shows that what appears to be earthen and natural is synthetic, exploitative, and prohibitively expensive: “It [survivalism and adventure] was a preoccupation…that had led to the rape and pillage of the Southern Hemisphere,” she writes.

Those in charge insist that taste is fluid, adaptable and pliable by anyone keen enough to study its changing codes. For this reason, many believe that “good taste” can be achieved by hanging around the right people and becoming a well-appointed cultural consumer. Olah, who was not born into wealth but went on to attend Oxford University, recalls understanding “early on” that her security depended on being able to emulate the behaviors and preferences of those in power: schoolteachers, university admissions staff, job recruiters, bank managers, and rental agents. Ideas of taste are ever-changing, differing from person to person, group to group, and situation to situation. Indeed, “tastefulness,” as Olah understands it, refers to the dominant culture, the model set by the most influential.

By manipulating her image and style, perfecting certain mannerisms and changing her accent, the infamous Anna Delvey—or, as she was formally known, Anna Sorkin—was accepted as a member of New York’s elite, conning friends, banks, and hotels. Failing to adhere to such standards is regarded as shameful and wrong, an expectation that excuses bigotry and inequality. In a close reading of one episode of The Sopranos, Olah recalls how Carmela and Tony’s choice of colorful glassware is mocked in a conversation about the family’s criminal convictions, with “Murano Glass (at that time at least) almost constituting a crime worse than murder.” Taste, however, is not to be confused with expertise; “disciplines are not elitist for the fact that they require learning,” she observes.

What all these examples attest to is that Olah’s preferred definition of taste, or at least its expression, is far from coming into being. For Olah, taste ought to be varied, led by personal quirks and preferences, separated from the realm of the culture at large. Our likes and dislikes should come from a deep desire, made up of individual choices that may change and develop over time, without the fear of being judged.

At times, however, Bad Taste succumbs to judgment, the very thing Olah wants to dispel: For example, she describes Tough Mudder, a corporatized adventure race completed by 6 million people across the world, as “an event I can barely bring myself to type.” But generally, her analysis of tastefulness, which most of us have participated in or strived to attain at some point, is well-grounded, despite the tangents.

Crucially, Olah mocks herself. In one story, she recalls the bemusement of her family as they opened the tin cups and herbal toothpaste that she had saved up to buy. In another, she reminisces about a trip to Marseille in the South of France, where she paid £100 for a “close to death” sailboat trip with a local, organized by the house-sharing website Airbnb: The skipper, a Welsh man and recent expat, said he was thankful to finally have people to share his new hobby with.

She has been a victim of taste, too. Olah was once rejected by a company for being a “poor cultural fit,” while another time a man—upon seeing her naked for the first time—mentioned that her ass (“properly big and beautiful and fat”) was incongruous with his impression of her as a writer and all the austere connotations that a life of letters might suggest. Writing advertising copy for juice cleanses, Olah has even played the role of tastemaker: Her words sold a diet product without ever mentioning weight loss, referring to “cleanliness” but also “achievement” and “gratification.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →While defying taste only creates new strains of consumerism, Olah asks us to dispense with the tyrannies that make us miserable, particularly those that require upkeep. “It is the condemnation of merely going out, sunbathing, walking aimlessly, sitting in the park, reading for hours or staring at the sky,” she writes. Seek pleasure instead, she advises. For her, this includes reading Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights, which hinges on a scene in which Catherine and Heathcliff are caught peering through the window of a mansion. But as Catherine later finds out, the world inside is very different from the one outside that window.

Support independent journalism that exposes oligarchs and profiteers

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation