The Problematic Past, Present, and Future of Inequality Studies

Branko Milanović’s century-spanning intellectual history of inequality in economic theory reveals the ideological reasons behind the field’s resurgence in the last few decades.

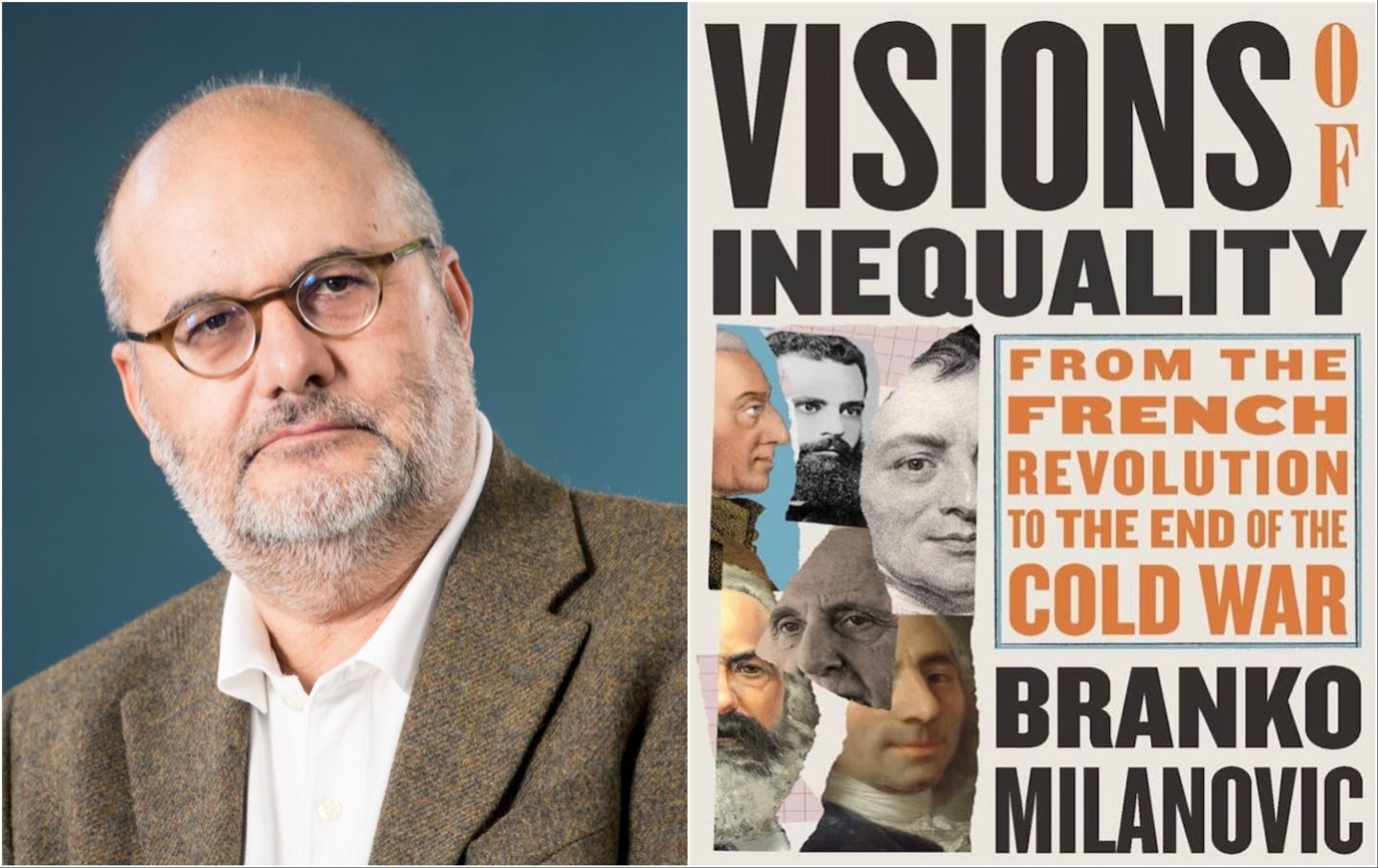

Branko Milanovic, 2017.

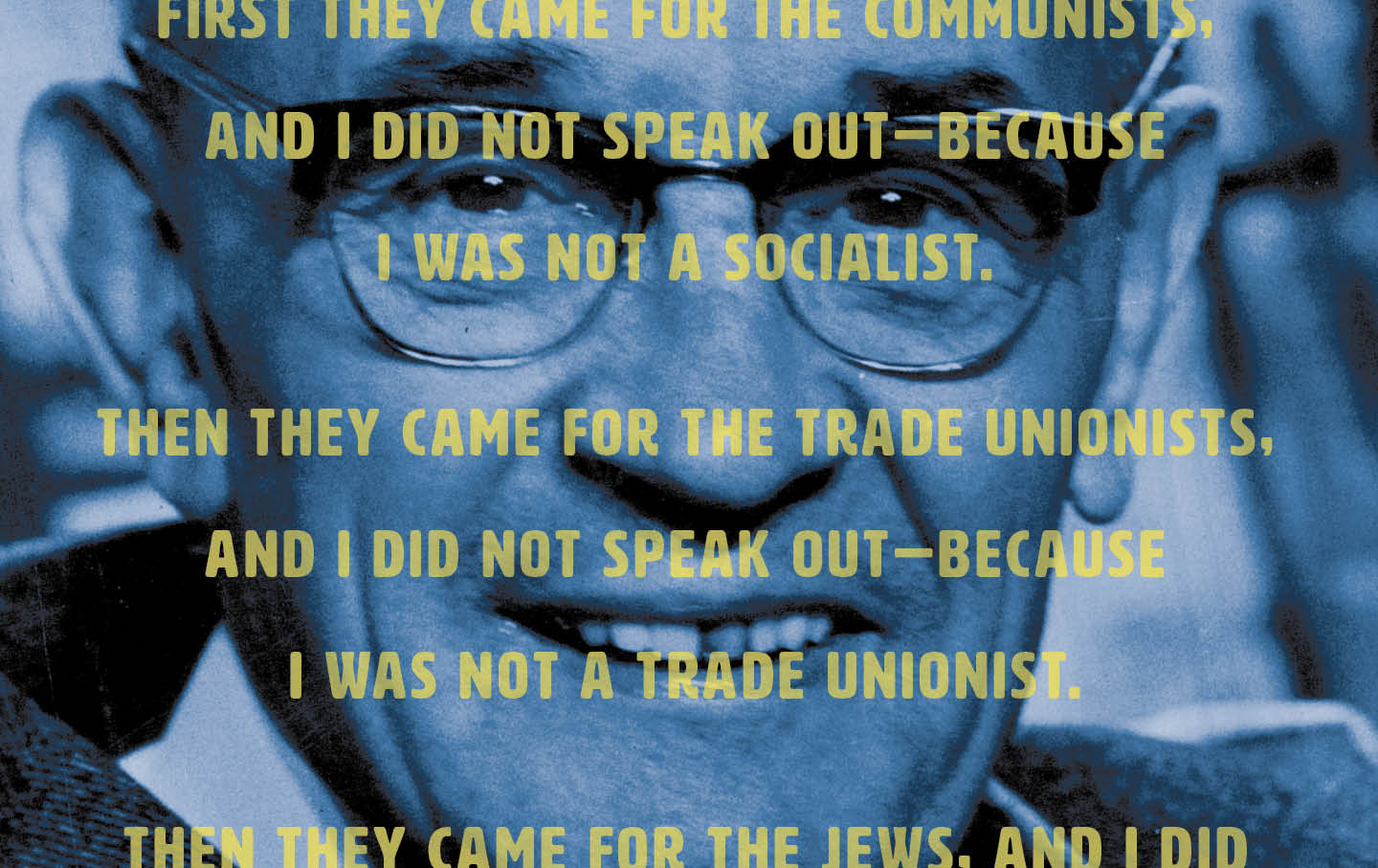

Photo by Roberto Ricciuti/Getty ImagesBranko Milanović’s Visions of Inequality: From the French Revolution to the End of the Cold War is an intellectual history of how leading economists since the 18th century, from Adam Smith to Karl Marx and beyond, have thought about income distribution and inequality.

Milanović, an economics research professor at the CUNY Graduate Center, seeks to explain why studies on inequality suffered a drastic decline during the Cold War, only to return with a vengeance over the last decade or so. His answer suggests that during the Cold War, the ruling elites of both the United States and the Soviet Union sought to deny class differences under their respective regimes, in order to promote the superiority of their own ideology against their rival’s. Yet, despite the US victory in the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet economic system, inequality has not only persisted in the West but grown in the last few decades.

This increasing disparity confounds the attempts by Cold War liberals to downplay or mask the realities of expanding economic inequality. Hence, Milanović argues, the current revival of inequality studies, to which his new book contributes.

The Nation spoke with Milanović about the role that class played in the economic thought of Smith, David Ricardo, and Marx, as well as Vilfredo Pareto’s elite theory and its relevance for today, the idea of “Cold War economics,” and the current state and future of inequality studies. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

—Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins

Daniel Steinmetz-Jenkins: Would it be correct to say that the history that Visions of Inequality chronicles is ultimately a story about the rise and fall of class analysis in thinking about economics? All the thinkers you examine from the 18th to the 19th centuries—François Quesnay, Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Karl Marx—assumed that class was essential for understanding inequality. And as class analysis faded among professional economists in the 20th century, so did studies of economic inequality.

Branko Milanović: To some extent, yes. The class distinctions between landlords, capitalists, and workers that were a key theme for Smith, Ricardo, and Marx have become less salient in modern capitalism. Landlords have, as Marx already noticed, become just ordinary capitalists who own land. So even in the 19th century, in the most advanced countries—this needs to be underlined; it certainly did not apply to Russia and India—the class structure had become simplified. The empirical basis for the distinction between classes was the difference in levels of incomes: Owners of capital were not only, on average, better off than workers, but very few workers could aspire to have incomes like those associated with capitalists. Workers did not, in terms of income, overlap at all with owners of capital. This is no longer the case today. There are very high labor incomes, and as the results of recent work have shown, there are people at the top of the US income distribution who are among both the top 10 percent of capitalists and the top 10 percent of workers. They are both capital- and labor-rich. This is not a development that Marx could have imagined.

But two important features of class analysis do remain. First, capital incomes are still extremely concentrated among the rich. In other words, to be rich still means to have a high income from property. Financial capital is so concentrated that some 90 percent of all financial capital in the United States is owned by the top 10 percent of people. Second, there is an unbridgeable and fundamental difference between income from labor and from ownership of assets. One type of income requires constant physical and mental effort; the other does not. It is not for nothing that, in English statistics, income from capital was called “unearned income.”

Therefore, the disregard of class analysis was and is premature. While the class divisions are nowhere as sharp in modern capitalism as they used to be under “classical” capitalism, they nevertheless still exist. The fading of class analyses can thus be explained not solely by the less salient cleavage between capitalists and workers, but by political pressures to pretend that modern capitalism has entirely overcome that cleavage. This is, simply, empirically not true. And the corollary of such an ignorance of class reality was an unwillingness to study inequality seriously or to take it seriously as an economic topic.

DS: Let’s try to unpack this argument a bit more by first looking at your discussion of Karl Marx. You insist that Marx was uninterested in questions of equality, insofar as any struggle to reduce inequality would lead to mere reformism at best so long as the background institutions of capitalism remained in place. Does this mean, in theory, that once the capitalist system is overturned and replaced by just institutions, high income differentials would no longer matter?

BM: It is very difficult to interpret Marx on this point, because his writings on the future socialist society are so scant. Moreover, the scarcity of such writings is not accidental: It derives from Marx’s profound aversion to “utopian” thinkers who tried to describe such future societies. His dislike of Proudhon and Fourier can largely be seen as related to that. Marx thought that he had discovered impersonal forces of history, the logic of history, that would lead to the abolition of capitalism. It was not up to him to describe in detail the organization of the future society.

But leaving for a moment this (important) issue aside, I will try to answer your question directly: One could say that Marx would be unlikely to believe that income inequality could be high under socialism. Why? First, capital assets would be nationalized and the income from them distributed to everyone. That would obviously reduce inequality. Second, the division between intellectual and manual labor would be lessened and the wage differentials compressed. Using contemporary language, we would say that the skill premium would be reduced, not least because free schooling afforded to all would reduce the need to compensate more skilled labor for the expenses incurred during the period of studies. Third, there would be no unemployment; the state would give jobs to all. Fourth, the absence of private ownership of capital would mean that productive assets could not be transmitted across generations. Perhaps some lucky kids could inherit a nice apartment, but they could never inherit a factory or financial assets that would provide them with income without work. All of these factors, I believe Marx would say, would reduce inequality, and perhaps there would be no need to be unduly concerned with it under socialism.

His attitude, shared by many Marxists, is not dissimilar to Friedrich Hayek’s view that once the fair and just background institutions (in Hayek’s case, of a full market economy) are established, inequality becomes irrelevant. In Hayek’s world, everybody is paid by somebody for whom they have provided some good or service; in Marx’s world, everyone is a worker, and everyone is given the same opportunity. Hayek does allow for some minimum social support of the indigent—that’s where his concern with inequality, or rather with poverty, comes in—but Marx would probably answer that even that may be superfluous in a society where the state is the employer of last resort.

Donate Now to Power The Nation.

Readers like you make our independent journalism possible.

DS: How does this discussion relate to questions of economic inequality in the Soviet Union during the Cold War?

BM: What I just said about Marx’s (probable) view about inequality under socialism was basically shared by the Soviet Union and communist countries more broadly. So I do not think that they departed from Marx. The problem was that in the Soviet Union and other communist countries, another phenomenon not envisaged by Marx, but envisaged by thinkers with such different ideological positions as Vilfredo Pareto and Mikhail Bakunin, happened: the creation of an upper class that was distinguished from the rest of the population not by the ownership of the means of production, but by their position in a bureaucratic hierarchy. Thus a new class society was born where we can say that the income from the nationalized capital was not equally shared, nor used only for the advancement of society, but was, in part, appropriated by the new leaders.

This is how inequality reemerged in socialist societies. And studying that inequality, as it so deeply challenged the view of ideologues that the new society was classless and equal, was discouraged. The data were not collected, or when collected were not made easily available; studies of inequality were considered “subversive” or at least “sensitive,” and the writers of such works were punished.

But, interestingly, there was not much interest in studying inequality among the dissidents either. Why? Because the dissidents’ interest was focused on the lack of political rights, and they tended to be, in terms of economics, right-wing or neoliberal. They too, like the party apparatchiks, were uninterested in issues of inequality; in fact, they often held that there was too much equality under socialism. Most of them, and increasingly so as we move closer to the 1990s, wanted both capitalism and more inequality.

DS: Does your notion of “Cold War economics” suggest a convergence between the two superpowers regarding their economists’ turning away from class analysis during the Cold War? In both, the lack of interest in examining economic inequality based on class difference was inseparable from the elites of these regimes being engaged in a propaganda war over the superiority of their opposing ideologies. To admit class difference would have been to reveal a problem with the ruling elite, and therefore they downplayed real issues of economic inequality.

BM: Yes, that’s absolutely one of the key theses of the book. I became very aware while writing this book that the key definitional relation in both systems—the power of bureaucracy in one and the power of capitalists in the other—was not studied, or was hardly studied at all, empirically. Under Cold War economics, both systems wanted to avoid the real discussion of what makes them unequal, in economic and political terms. Under socialism, political inequality tended to translate into economic inequality; under capitalism, economic inequality enabled political inequality.

The “discouragement” of studies of inequality began in the Soviet Union within a decade after the Bolshevik Revolution. Up to approximately 1927–28, inequalities between town and countryside, between manual and nonmanual labor, etc., were empirically documented and much discussed in the Soviet Union. This gradually waned and then ended with Stalinism.

The situation in Western economics was more confused or chaotic in the interwar period; then Simon Kuznets wrote on inequality during the period of “high optimism” in the United States, when the US enjoyed unchallenged economic superiority, the highest per capita income in the world, and decreasing inequality. It is only later, from the mid-1960s, and most obviously with the ascendance of Reaganomics, that the study of income inequality all but disappeared in the United States.

Of course, there were many individual empirical studies of the skill premium, the effect of trade on labor incomes, and the like, but my point is that what was absent were integrative studies of inequality that combine a clear narrative, theory, and empirics. Such integrative studies by necessity involve politics, because inequality is always a political phenomenon: It deals with the distribution of the “pie” (national income). We did not have such work. Economists either produced largely meaningless theoretical papers that treated everybody as an “agent” (often an “infinitely lived agent with perfect foresight”) despite the obvious differences between capital and labor, or they did über-empirical studies that never came close to nesting income distribution within politics. I criticize myself for doing the latter.

DS: Given all this, there is a way of reading your book that would suggest that the economist Vilfredo Pareto, often deemed a fascist or a pseudo-fascist, is the hero of the story, at least in one particular sense. His famous idea of the circulation of the elites, and their ability to manipulate the masses for their own power, seems to go quite well with your notion of Cold War economics. Would you agree?

BM: My objective was not to rank the economists whom I profiled. Moreover, as I mention, I always tried to take a “sympathetic” position in the sense that I tried to answer in their stead how (I believe) they would have seen the forces of economic inequality in their time and in the future. I abandon that approach only in Chapter VII, which is very critical of the most recent period and the work—or rather lack of work—under Cold War economics.

But I do agree with you that Pareto comes across as an unlikely hero, for two reasons: first, his belief that different political systems are compatible with the same level of economic inequality. This view can in part be validated by the socialist experience. For sure, numerically, income inequality in socialist economies tended to be less than in capitalist countries as a whole—but when you compare it with the advanced capitalist welfare states, the gap disappears. Hungary was not more equal than Austria, nor Poland than Finland.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Second, Pareto’s cynical view that all societies are ruled by elites that try to claim that they are not the elite finds itself confirmed today in everything we observe: in the high share of income appropriated by the top 1 percent (“the new elite”) or in their political influence. Pareto, a student of Machiavelli, would be very much at ease in today’s United States: An elite composed of “foxes” (as opposed to “lions”) is skillfully using propaganda to claim that it is not the elite and that the society is democratic.

DS: The major exception to your notion of Cold War economics would be the Latin America dependency theorists. What allowed these economists to see past the trends of their time?

BM: I wish I wrote more on that—but I was limited by my own lack of full familiarity with the main authors of the dependency school. I was more influenced by Samir Amin, who is very close to the dependency theorists and whom I thought at one point to profile as the seventh great figure (chronologically coming after Kuznets).

Why was the dependencia school important for the study of inequality? Because of the changed focus. For the first time, it was argued that inequality within a society is determined not only by social forces within that society but also by the external environment, where globally powerful forces have an interest in making the distribution in the “periphery” such that the “periphery” continues to play its assigned role. Thus, as Samir Amin argued, the comprador bourgeoisie in Egypt is not maintained in that position by domestic forces only, but by foreign forces too—or perhaps even mostly by the foreign.

What made Latin America special was that high inequality there was impossible to hide. Nobody living in Latin America could argue that capitalism does not reproduce inequality or that economic inequality does not matter. That blinding reality was just impossible to ignore, and people wrote about it and studied it empirically by dividing societies by class, by looking at the rich landowners at one end of the spectrum and the Indigenous population at the other.

Second, Latin America was less “committed” to one or the other side in the Cold War. This made its economists freer to write about the topics, like income and wealth inequality, that were considered politically inappropriate in the United States and then slowly “canceled” from the leading economic journals.

DS: The decline of inequality studies has now reversed itself. Typical answers as to why would include the 2008 financial crisis, the explosion of interest in neoliberalism, trying to imagine what comes after its decline, etc. How, though, do you make sense of this change?

BM: Things have changed dramatically. The chain of events that began with the financial crisis makes any claims that the United States, after the end of the Cold War, was a classless society tenuous. It is impossible to mask the large increases in the top 1 percent’s share by the easy borrowing of the middle classes. It is impossible to mask the absence of good jobs by pointing to a decrease in the relative prices of household gadgets. It is impossible to claim that there is no elite when its spending patterns are so different from those of the rest of the population, and its political power, expressed in campaign contributions, is unrivaled. The rising inequality in many other countries and the much more pronounced political role of plutocrats and oligarchs, in part revealed by the globalization of information, also makes inequality harder to ignore. Thus, only seemingly paradoxically, I believe that inequality studies have a bright future precisely because today’s societies are increasingly plutocratic and ruled by elites.

DS: What is the future of inequality studies as you see it? Where is there work to be done?

BM: We do have a revival in four areas: the reacceptance of class analysis; the reemergence of the idea of an elite, coming now in the form of the top 1 percent; the expansion into new areas of research like global inequality; and, finally, through a much greater use of historical social tables. These are tables that list classes or large groups of people giving their average estimated incomes. This last method is the only way to study inequality in past societies. Economists have used it to estimate inequality in the Roman Empire, Byzantium, the Aztec Empire, medieval Europe and Japan, etc. We are just learning about how unequal we—the human species—have been in the historical past, and that tells us something also about our present and perhaps even about our future.