How Asset Managers Ruined Our Lives

Firms like Blackstone have made investments in real estate, energy, and infrastructure to become the world’s most crooked landlords and bill collectors.

It would be a mistake to dismiss the question “What is an asset?” as a trivial matter. To answer this question in the context of today’s inscrutable global marketplace, one must plunge into a complex realm of legal terminology, financial technology, and corporate strategy. When the focus is narrowed to so-called “real” assets—tangible instruments like housing and infrastructure, as opposed to intangible, purely “financial” assets like bank deposits or a corporation’s share capital—the answers become even more elusive.

Books in review

Our Lives in Their Portfolios: Why Asset Managers Own the World

Buy this bookNot long ago, the provision of housing, for example, in developed countries was largely the purview of state governments, pension funds, and small, individual mom-and-pop landlords renting out a handful of units at most. Now—and it is indeed a relatively recent phenomenon—residential property is big business, as asset managers systematically purchase, operate, and sell (this is a crucial piece of the puzzle) single-family rental units and multifamily apartment blocks at scale, turning housing into a collective investment vehicle. We know who the major players in this space are: Blackstone in the United States, Brookfield Asset Management in Canada, and the Grosvenor Group in the United Kingdom are just three of the largest institutional participants in housing, but there are dozens more. The decisions and transactions of these gargantuan firms—the metric typically used to measure them is “assets under management” (AUM), which is estimated at above $100 trillion globally—are almost entirely shielded from public scrutiny, cloaked behind limited disclosure requirements, in addition to layers upon layers of holding companies, subsidiaries, special-purpose vehicles, general partners, limited partners, and investment funds. Sometimes we are allowed a glimpse into their top-floor, closed-door dealings in announcements and briefs; such was the case with Blackstone’s recent announcement of Blackstone Real Estate Partners X, its biggest real estate fund ever, a war chest positioned to amass $30.4 billion in property.

The metabolism of the urban landscape is increasingly filtered through such private, “alternative” asset-management firms. Their monolithic portfolios include—in addition to large swaths of residential property—the critical infrastructures undergirding major metropolises: Energy, water and wastewater, transportation, telecommunications, schools and hospitals, and farmland are the six major investment areas identified by Brett Christophers in Our Lives in Their Portfolios: Why Asset Managers Own the World. Throughout the book, Christophers nimbly unpacks how the sophisticated corporate strategies deployed by asset managers—devised and streamlined over decades—have immediate and drastic effects on the daily lives of all who depend on their services. Attempting to unravel the intricate workings of those who manage such “alternative” investments reveals the formidable fortresses of opacity built into the very structure of their business model. But by demystifying the management of assets, one can identify woefully underappreciated shifts in the management of contemporary life itself.

At the center of our “asset-manager society”—the term Christophers coins to describe this transformation of everyday necessities into assets—is the investment fund. Investment funds, such as Blackstone Real Estate Partners X, comprise this new society’s core: “The wealth of societies in which the asset-management industry prevails appears as an immense collection of investment funds,” Christophers writes. Single firms like Blackstone manage multiple funds; crucially, it is their funds that make the investments, not the firms themselves. An individual investment fund, which is unlisted on any stock exchange (it requires exclusive invitation or solicitation), focuses on a specific investment area—a particular “asset class” or “sub-class”—for which, once announced, millions or even billions of dollars are raised. It is primarily the money of other people that is pooled into these funds, but rarely that of individual or “household” or “retail” investors. Rather, the money comes from some of the most capital-flush entities on the planet—institutional investors like pension plans, insurance companies, and sovereign-wealth funds—who make “commitments” to the funds, from which managers can draw when the time comes to purchase assets. While managers do typically commit a small portion of their own capital to each fund, this is appropriately seen as a symbolic gesture: To put a little skin in the game is to show shared incentives, palliating third-party investor anxiety. In other words, what these asset managers can buy is determined solely by what they can eke out of their wealthy backers, and so it is to the latter that they are beholden, not the broader public that relies on the assets they manage.

The investment funds of asset managers, Our Lives in Their Portfolios argues, extend to a novel administration of social wealth, which boilerplate critiques of “financialization” fail to adequately appreciate. To illustrate their peculiarity, Christophers makes a somewhat clumsily named—and yet crucial—categorical distinction between asset-manager society and asset-manager capitalism. His distinction rests on the nature of the assets themselves—between “real” and “financial” ones—but it extends to two entirely different organizational forms and managerial regimes.

Many, if not most, of the big-name asset managers invest in financial assets. Firms like Blackstone, Vanguard, and State Street hold immense stakes in companies listed and traded on stock exchanges; indeed, these firms and their kin have powerfully remade the nature of financial markets themselves, to the extent that they now hold between 30 and 40 percent of the average S&P 500–listed company’s equity. This activity—the trading of stocks and bonds and cash and precious metals, even when done by massive brokerages—is subsumed under the category of asset manager capitalism. In that sphere, due to notoriously byzantine securities laws designed to protect retail investors, firms are subject to considerable public scrutiny and regulatory oversight, and they do not own or control outright the physical assets on their portfolio companies’ balance sheets. Under Christophers’s schema, while asset-manager capitalism consists of highly visible actors in financial markets, the more insidious pursuits occur behind the scenes, in asset-manager society.

In asset-manager society, investment funds mediate the coordinated purchase of physical assets. Through funds, asset managers and their “limited partners”—the legal form assumed by investor clients—become goliaths with the power to directly capture the essential material bedrock of everyday life. In exchange for their services, the populace has no choice but to pay rents, fees, tolls, bills, and taxes, usually without full knowledge of the ultimate recipient.

This is due to the complex operational choreography by which investments are circuitously routed: first through the establishment of an armory of diversified funds, then through an array of “general partners”—legal entities, established by managers, that assume liability. But asset managers don’t just buy the stuff; they also must maintain it. General partners are assigned this task, and they are often difficult to tie back to the managers themselves. This is how you might end up sending rent payments to an innocuous management company that are ultimately funneled all the way up to the accounts of Blackstone. The latter is under no legal obligation to report the holdings or dealings of its unlisted funds, so we only know what they tell us, which rarely includes disclosing the identity of their limited partners.

One integral characteristic of asset-manager society is its time horizon. As Christophers emphasizes, the asset managers of real assets buy in order to sell. This feature of their business model is one of many appropriated from the world of private equity; in industry-speak, their investment funds are usually “closed-end,” a term referring to any fund whose capital is tied up in assets until an explicitly stated termination date. This means that, at the inauguration of each fund, managers indicate the precise time at which all assets in the fund will be liquidated and all accumulated profits distributed to the limited partners proportional to their commitments (minus the fees those clients pay to the manager). Managers also outline a plan of action by which they intend to achieve a desired return on investment, known as the “hurdle rate.” So once the fund purchases an asset—such as an apartment block, a highway, a hospital, or an airport—the asset manager’s sole purpose is to prepare that purchase for resale (which will almost certainly be to another asset manager).

While Christophers notes that the average closed-end fund’s lifespan is usually between seven and 12 years, it can be much shorter than that. He cites the remarkable case of Blackstone’s acquisition in 2016 of a majority voting stake in the Swedish property management company D. Carnegie & Co, since renamed Hembla. By 2018—just two years after the deal—Hembla had increased its ownership of housing stock in the Greater Stockholm area from 16,000 to 21,000 apartments, and Blackstone had wagered its majority voting stake into a majority ownership stake. Rent increases swiftly followed across Hembla’s portfolio of properties—by an average of 50 percent per unit over the course of the following year—before Blackstone’s tenure as landlord ended in 2019. In that year, Blackstone sold its stake in the company to the German asset manager Vonovia at a profit of $600 million.

Bracketing the astronomical returns, several aspects of closed-end housing funds must be emphasized. First, they have an immediate impact on rent inflation: Since investments like Blackstone’s in Sweden must be made at scale, asset managers carry significant market power, with the ability to display price-leading behavior in targeted geographic areas. When fund managers, seeking quick and easy profits, strategically raise rents across tens of thousands of densely packed units, rental prices in the surrounding market necessarily follow, as other landlords—corporate and otherwise—ensure that their rents keep pace. Second, the outsize returns of closed-end housing funds are not directly attributable to the monthly rental payments collected from tenants. When asset managers do raise rents on their units, it is merely one weapon wielded to entice prospective buyers: Reliable income streams signal sound investments. The ultimate source of Blackstone’s profits was the sale of its stake in Hembla to Vinovia.

Finally, the methodical short-termism of these “alternative” asset managers is at odds with the intrinsically long-term nature of the assets themselves. In housing, the sole beneficiaries of the fund managers’ objective to condense the time, as much as possible, between purchase and sale are the shareholders—not the tenants. Indeed, such purchases are often made at the expense of tenants, especially during times of financial crisis.

This last point is thrown more sharply into relief in the realm of infrastructure. Economic theory since Adam Smith holds that the state’s role in a capitalist economy is to finance projects that no private-sector actor will rationally pursue. This is because the full monetary return of long-dated infrastructural investments is difficult to measure, let alone appropriate by an individual firm. The state, in Smith’s view, must bear these capital-intensive burdens, which are necessary for the reproduction of the social body but have long gestation periods and high risk profiles at which return-hungry investors inevitably balk. Until the 1990s, private-equity-style forays into infrastructure were either unavailable or seen as radioactive. But the cunning of financial reason soars beyond these worldly particulars, guided as it is toward the lofty heights of the internal rate of return.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The crucial point that Christophers hammers home is that the orthodoxy of urban planning could not have shifted from Smith’s rule of thumb without the enthusiastic participation of the state. On behalf of “alternative” asset managers, states shoulder the risk. If this does not take the form of public-private partnerships (PPPs)—as it often does in the United Kingdom, which Christophers labels the “historic heartland” of these initiatives—then state governments can play a de-risking function for private-sector investors, whether through co-investments, loss absorption, or revenue guarantees. International bodies such as the World Bank now openly encourage such interventions, as government-led risk offsetting has become their favored approach to closing the so-called “infrastructure gap.”

Who benefits from all this? Stephen Schwarzman, the chairman and CEO of Blackstone, would have you believe that it is primarily the mythological “ordinary citizen,” on whose behalf asset managers claim to act—all those “teachers, nurses, and firefighters” whose pension money is committed to closed-end funds. For as long as private equity has existed, this line has served as its principal ideological self-justification.

On the face of it, asset managers certainly do put the retirement savings of regular people to work. They even allocate pension savings to profitable ventures. But when such investments succeed, low-income workers benefit only by accident; the largest gains are realized by a few senior executives atop each fund—this is how the annual salary of the average employee at Blackstone stands at over $2 million—and the distribution of retirement savings mirrors the lopsided distribution of social wealth more broadly.

To boot, workers at the bottom are more likely to have their returns clawed back by the rising rents and utility fees that make fund managers’ assets attractive to other buyers. Importantly, pension funds are only one category of limited partner; their capital is mixed with that of less PR-friendly entities, such as Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund. Further, when investments fail—as they often do—it is ordinary citizens who end up losing, as systematic de-risking, compounded by debt financing, guarantees that all losses are socialized. Reduced to mere customers, Schwarzman’s “ordinary citizens” witness the deformation of their welfare into collateral damage. As long as the state is beholden to asset managers, the question of whose interests take precedence will continue to be answered by magnitudes of capital.

More from The Nation

The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…” The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…”

In his celebrated mea culpa, the German pastor Martin Niemöller blamed his failure to speak out against the Nazis on indifference. Was that the whole reason?

“The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy “The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy

The new show from the creators of The Office reminds us that their comedic style does now work in every “workplace in the world.”

The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme” The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme”

Josh Safdie’s first solo effort, an antic sports movie, revels in a darker side of the American dream.

John Updike, Letter Writer John Updike, Letter Writer

A brilliant prose stylist, confident, amiable, and wonderfully lucid when talking about other people’s problems, Updike rarely confessed or confronted his own.

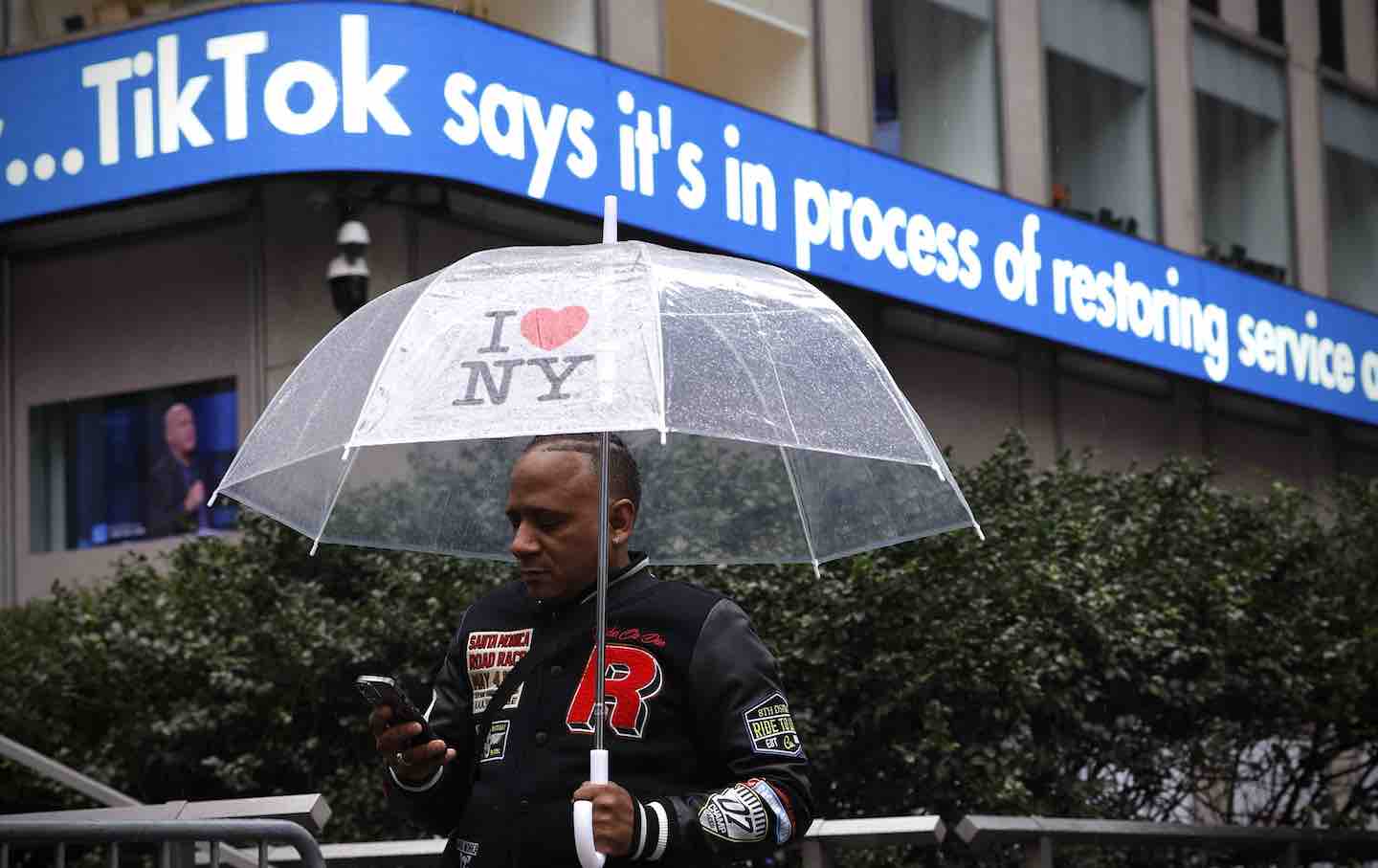

TikTok’s Incomplete Story TikTok’s Incomplete Story

The company has transformed the very nature of social media, and in the process it has mutated as well—from tech unicorn to geopolitical chesspiece.