The Dubious Return of the Brutalists

Why the stark 20th-century architectural style is back in vogue.

The Paul Rudolph-designed headquarters of the Burroughs Wellcome pharmaceutical company in 2020, shortly before its demolition.

(Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)On April 21, 1989, members of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) invaded the headquarters of Burroughs Wellcome, the pharmaceutical behemoth behind AZT, the only approved treatment for HIV. Burroughs Wellcome billed patients $8,000 a year for the drug; to the seasoned New York–based activists, it was a white-collar mugging—literally “your money or your life!” After infiltrating Burroughs Wellcome’s Brutalist concrete ziggurat, which loomed over a highway in North Carolina’s Research Triangle, ACT UP’s self-styled Power Drill Team turned the structure’s harsh materials against it. Driving rivets into steel plates, the activists locked themselves in place to occupy the building.

ACT UP had grown out of the tight-knit queer community in the old tenements and illegal industrial lofts of a depopulated downtown New York where rent was cheap and squatting was possible. Dedicated to winning dignity and equality for the marginalized, the group proved Jane Jacobs’s adage “New ideas need old buildings.”

Corporate America disagreed: For the era’s titans of industry, new ideas needed new buildings. Setting out for the exurban fringe, they commissioned countless sculptural structures that their PR reps invariably proclaimed “iconic.” Among them was Gordon Bunschaft’s American Can Company headquarters in Fairfield County, Connecticut, three layers of low-slung concrete slabs that boasted 1,700 parking spaces, and Eero Saarinen’s Bell Labs Complex in Monmouth County, New Jersey, a black cube set between two fake lakes.

The arresting Burroughs Wellcome headquarters, commissioned in 1969 and opened in 1972, was a classic of the form. It stood as a touchstone of Brutalism, an offshoot of the Modernist movement that shunned smooth metal-and-glass curtain walls in favor of rough-hewn concrete facades. Emerging from the breakneck effort to rebuild European cities after the destruction of World War II, Brutalism embraced poured concrete for its speed and efficiency. With engineering advances in the postwar decades, architects could mount ever more complicated and precariously balanced concrete elements, blurring the line between architecture and sculpture. When the urban crisis of the 1970s induced a bunker mentality among the rich and powerful, the Brutalist style found plenty of patrons: A bunker mentality, after all, needs its bunkers. Burroughs Wellcome’s corporate temple, a pile of beige concrete pods mounted on pilotis and jutting out at odd angles, was one of the movement’s finest creations. It was produced by the leading Brutalist architect, Paul Rudolph.

Anointed the successor to the Modernist master Le Corbusier by The New York Times Magazine, Rudolph’s rise was quick. By age 40, he had become the head of architecture at Yale University and soon after founded his eponymous architecture firm in Manhattan, where he lived uptown, in a studiously private relationship with a man. Rudolph’s landmark Art and Architecture Building at Yale made the cover of all the leading design magazines in 1963 and broke through into the wider culture. Design critic Paul Goldberger recently compared its critical embrace to the fawning reception decades later that greeted Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. Rudolph, with his conservative suits, crew-cut flattop, and White Anglo-Saxon Protestant pedigree, resembled the corporate figures who commissioned his buildings. And his Brutalist works were unignorable: Love ’em or hate ’em, even those who considered them architectural train wrecks couldn’t look away.

But a backlash was already brewing. In 1969, fires tore through the Art and Architecture Building; rumor had it that the spark had been set by Rudolph’s own students. With the Vietnam War raging, the rising generation was turning against the power elite and its court architects. Professor Rudolph’s bespoke campus perch, with its purposefully difficult-to-mount staircases and cold concrete resting-bitch-face turned against the downwardly mobile residents of New Haven, came to symbolize the worst of the older generation’s insular self-regard. After graduation, many of Rudolph’s students joined an architectural countermovement that embraced the traditional elements the Modernists had jettisoned: classical arches, columns, and pediments. Playfully integrating these flourishes into their contemporary structures, they launched Postmodernism. In tandem, critics like Jane Jacobs fostered a newfound appreciation for traditional urban fabric, casting a skeptical eye on the Modernists’ expanses (whose architectural renderings showed great crowds gathering to admire these inhabitable sculptures, but which were invariably windswept dead spaces in real life).

Shortly after his swift ascent, Rudolph found himself all but banished. His major late-career works were almost exclusively built in authoritarian-capitalist Asian locales—Hong Kong, Singapore, and Jakarta. In 1997, amid the yellowing newspaper clippings from his heyday, Rudolph died of mesothelioma, the cancer caused by asbestos inhalation. The architect had been felled by his own building materials.

In the decades after the Yale campus conflagration augured a backlash, Brutalism has never been fully rehabilitated. The Burroughs Wellcome headquarters, notably, was demolished in 2021. To this day, every mention of Brutalism comes with the defensive disclaimer that its name derives from the French term béton brut, for “poured concrete,” the style’s signature material. But that constant caveat is a tell: Most observers find something undeniably brutal in these harshly shelled structures. While Brutalism was celebrated by its adherents for its daring embrace of the new, there is a palpable coldness in the visual stamp it left on the world. And the people encased in these buildings expressed that—sometimes in quiet grumblings about their workspaces but, more worrisomely, also in their work. Can the cynical profiteering of Burroughs Wellcome be fully divorced from the structure itself—harsh and marooned away from society on the side of a highway?

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Yet Brutalism’s boosters are back today. As we increasingly spend our time in an online world of pure image, it is easy to get lost in a compelling picture, mistaking a blueprint or rendering for the building itself. And disillusionment with the contemporary can’t-do American city, where great public-works projects seem a thing of the past, has fostered a rose-tinted view of the old megaprojects.

Today’s movie of the moment is Brady Corbet’s The Brutalist, a three-and-a-half-hour epic starring Adrien Brody as a fictionalized Bauhaus-trained Hungarian Jewish architect struggling to bring the film’s eponymous style to a wary America. Meanwhile, the Metropolitan Museum of Art is currently showing “Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph.” As the Met’s first major show devoted to 20th-century architecture in decades, it’s a tremendous endorsement of Rudolph’s significance. Simultaneously, a quieter, thoughtful, even brooding exhibit, “Capital Brutalism,” is on view at the National Building Museum. It surveys Washington, DC’s extensive Brutalist inventory and ponders whether any of it is even salvageable. This cultural confluence makes clear that Brutalism is once again in the public eye. But is it being reckoned with in the public mind?

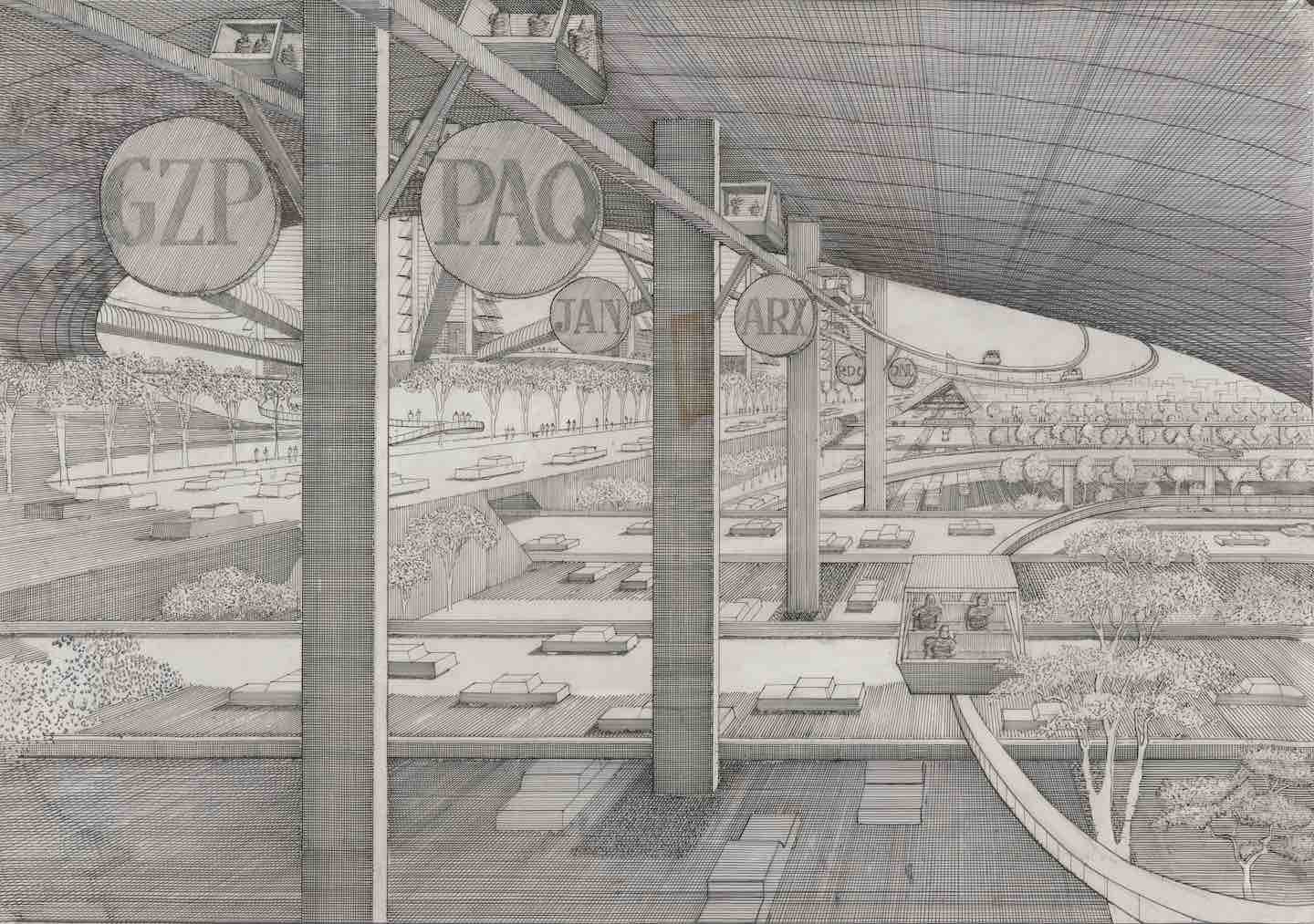

To enter the Rudolph retrospective at the Met is to be seduced. Enveloped in the museum’s 20th-century art galleries, the clean lines and daring spirit of Rudolph’s drawings place him comfortably in the company of the modern masters nearby. His geometric precision and imaginative forms echo Russian Constructivists like El Lissitzky. Exhibition photographs of Rudolph’s built works alluringly capture the interplay between light and shadow that animate the interiors and exteriors of his massive concrete structures. One featured building is a levitating layer cake improbably balanced on fluted columns; in another mock-up, a concrete snake of triangular apartment buildings slithers its way across Manhattan.

But Brutalism’s move from form to function is a journey from utopia to dystopia—a trajectory the curators pointedly ignore. Those photogenic fluted columns are from a parking garage that Rudolph jammed into the once-walkable heart of New Haven. A 1963 Vogue magazine feature, included in the galleries, shows Rudolph, dressed in a snappy suit, standing next to his gas guzzler on the parking garage’s roof. Could there be a more damning artifact of the misguided mid-century faith that the automobile would save the city? (Perhaps the parking lot itself, which still stands.) Even worse, that concrete snake is a sketch for the Lower Manhattan Expressway, Robert Moses’s dark dream of ramming a highway through Greenwich Village, which was only stopped by Jane Jacobs and her grassroots band of neighborhood activists. “Although never realized, the Lower Manhattan Expressway was one of Rudolph’s best-known—and most controversial—projects,” the exhibition text informs visitors, channeling the amoral deadpan of a Burroughs Wellcome annual report.

It is now a commonplace of freshman art-history classes that students learn that the modern museum is not art’s natural habitat. For thousands of years, humans created works to be displayed in other settings. Hauling, say, a statue of the Virgin Mary from a French cathedral or a Buddha from a Chinese cave temple into a museum constitutes a radical decontextualization of the piece, and any full understanding of the work must acknowledge this.

This caveat is even more crucial for architecture. More than any other form, architecture is constrained by external forces—budgets, zoning rules, fickle clients. And buildings, by their nature, must exist in an urban context (or at least, as with the Burroughs Wellcome headquarters, an exurban context). To treat a Rudolph design as a study in pure form—like a Brancusi sculpture—is to engage with it on the most superficial level. There is a temptation to treat Brutalism as an aesthetic without politics, but from New Haven to North Carolina to Singapore, Rudolph’s buildings betray a legible political concept: the technocrat as aristocrat. In so many of his projects, an educated elite hovers above the masses, even as it assures itself that—of course, undoubtedly, and needless to say—it serves the people.

Those fated to live or work in Brutalist structures do not have the luxury of appreciating them as mere sculptures. Disenfranchised until 1973, no Americans were more vulnerable to Brutalist urban renewal schemes than the residents of Washington, DC, before home rule. In the southwestern portion of the city, federal authorities bulldozed blocks by the dozen, uprooting an established working-class African American enclave to erect a full-scale Brutalist neighborhood centered on the newfangled L’Enfant Plaza office district. The smattering of public housing that was included in the renewal plan couldn’t make up for the vast swaths of residential destruction. At the end, 23,000 residents had been displaced and 1,500 businesses destroyed.

Today, Southwest DC is an urban graveyard. Still, a few of its headstones are temptingly stylish. Built under the then-new guidelines authored by Daniel Patrick Moynihan and adopted by the Kennedy administration, leading American architects—many of them European refugees—were tapped for these high-profile federal commissions. At the Department of Housing and Urban Development headquarters, designed by the Hungarian Jewish Bauhaus alumnus Marcel Breuer, metal disks hover over entryways like UFOs. Nearby, Gordon Bunschaft’s concrete doughnut, the Hirschhorn Museum, floats above the National Mall housing a collection of modern sculpture in a building that is itself a modern sculpture.

But a neighborhood of sculptures is a gallery at best—one where the concept of neighborliness doesn’t register. And among those who have to use these buildings, they’ve never been popular. George H.W. Bush’s HUD secretary, Jack Kemp, dismissed Breuer’s building as “ten floors of basement.” Shaun Donovan, who served in the same role under Barack Obama, called his office “among the most reviled buildings in all of Washington—and with good reason.”

In “Capital Brutalism,” the National Building Museum frames these structures as “Washington, DC’s most polarizing architectural landmarks” and mulls what should be done with this largely unloved inventory today. For reasons of cost, historic preservation, and carbon footprint, the curators call for adaptive reuse; as the current saying goes, the greenest building is the one you don’t build. Indeed, Brutalism’s embrace of poured concrete came with harrowing upfront environmental costs from the emissions released during production. And the costs are still accruing today, through the urban heat-island effect that the material exacerbates. As DC’s weather gets hotter, these structures retain more heat, necessitating greater use of energy-gobbling air-conditioning, which releases more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, which raise temperatures even further in a vicious, infernal cycle. In the exhibition, several leading architecture firms present mock-ups of retrofits that make Brutalism less brutal for both humans and the environment. Firms ranging from the daring Studio Gang to the dully corporate Gensler propose softening the buildings with shading greenery, neighborly coffee shops, and windows you can actually open.

Notably, one lone Brutalist megaproject escapes the curators’ call for change: the Washington Metro. It is undeniably a Brutalist masterpiece. An all-encompassing geometric world of hexagonal tile platforms with circular lights overhead and vaulted concrete ceilings made from tessellating polygons, this underground transportation system is the only place where the style fully delivers. With its spartan grandeur, it looks like what the ancient Romans might have built had they decided to build a subway. But the system’s location is key: A Brutalist sculpture gallery can work underground in a way that one at street level never could. Fitting unobtrusively into walkable neighborhoods, with just a few surgical insertions of staircases and escalators at street corners, the Metro is a good neighbor in the way the HUD headquarters never can be.

For all its merits, when the Metro opened in 1976, it proved the ultimate indictment of Brutalist urban renewal. In addition to the morning and evening rush hours, city planners were surprised to find that the new system also experienced a mid-day “lunch crunch.” Around noon, those sentenced to serve at HUD and the other massive federal edifices in Southwest DC were commuting to sections of the city that had been spared urban renewal’s wrecking ball just to meet their daily caloric needs. After the bulldozing of more than 1,000 businesses, Southwest DC’s barren Brutalist expanse was so devoid of corner stores, diners, and lunch spots that the neighborhood had been rendered incapable of supporting human life. It was literally unlivable.

Brutalist structures—even the train wrecks—unfailingly deliver eyeballs on Instagram and Pinterest, in design magazines and coffee-table books, and on innumerable creative-director mood boards. Late last year, the architecture website Dezeen ran the click-bait listicle “Ten striking buildings that draw attention from afar.” Spanning the world from Denmark to Denver, it unabashedly treated architecture as sculpture in the manner of the long-deceased Brutalists. Somewhere, Paul Rudolph is smiling.

In the realm of pure image, Brutalism has stood the test of time. Even at the nadir of his architectural reputation, Rudolph’s interiors remained Hollywood favorites. At the Met, a running video loop shows his structures in use as sets on the silver screen. In The Royal Tenenbaums, Ben Stiller and his fabulously wealthy, fantastically dysfunctional family barrel through Rudolph’s self-designed Manhattan townhouse, a white box of cantilevered stages with so little privacy that the ceiling of one floor was the bottom of the plexiglass bathtub above. In another clip, the Burroughs Wellcome headquarters serves as the set for a dystopian 1983 sci-fi flick, Brainstorm, in which greedy corporate executives turn their idealistic scientists’ breakthrough into a psy-ops torture device for the Pentagon. Surely ACT UP’s Power Drill Team had a bitter laugh at how art imitates life. Rudolph’s spaces, with their gravity-defying overhangs and moody shadows, are a cinematographer’s dream. One can almost forget that these are buildings, not cinematic backlots. But to evaluate them as architecture, one must resist that temptation. Architecture is inescapably political. It is the hidden hand that shapes how we come together in urban spaces—or don’t.

Fittingly, for our building-as-spectacle age, Brady Corbet’s The Brutalist ends not with the triumphant completion of a building but with the champagne-flute opening of a retrospective. At a fictionalized Venice Architecture Biennale, our now-elderly and wheelchair-bound protagonist is feted with a show, “Architecture and Utopia,” featuring photographs and models of his Brutalist works. When the exhibition becomes the highest form of architectural success, the question of whether a building functions on human terms—Can you walk up the stairs? Open the windows? Feed yourself?—becomes an afterthought. And the most crucial question of all—does a building bring out the best in us or our worst?—gets bulldozed entirely.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation