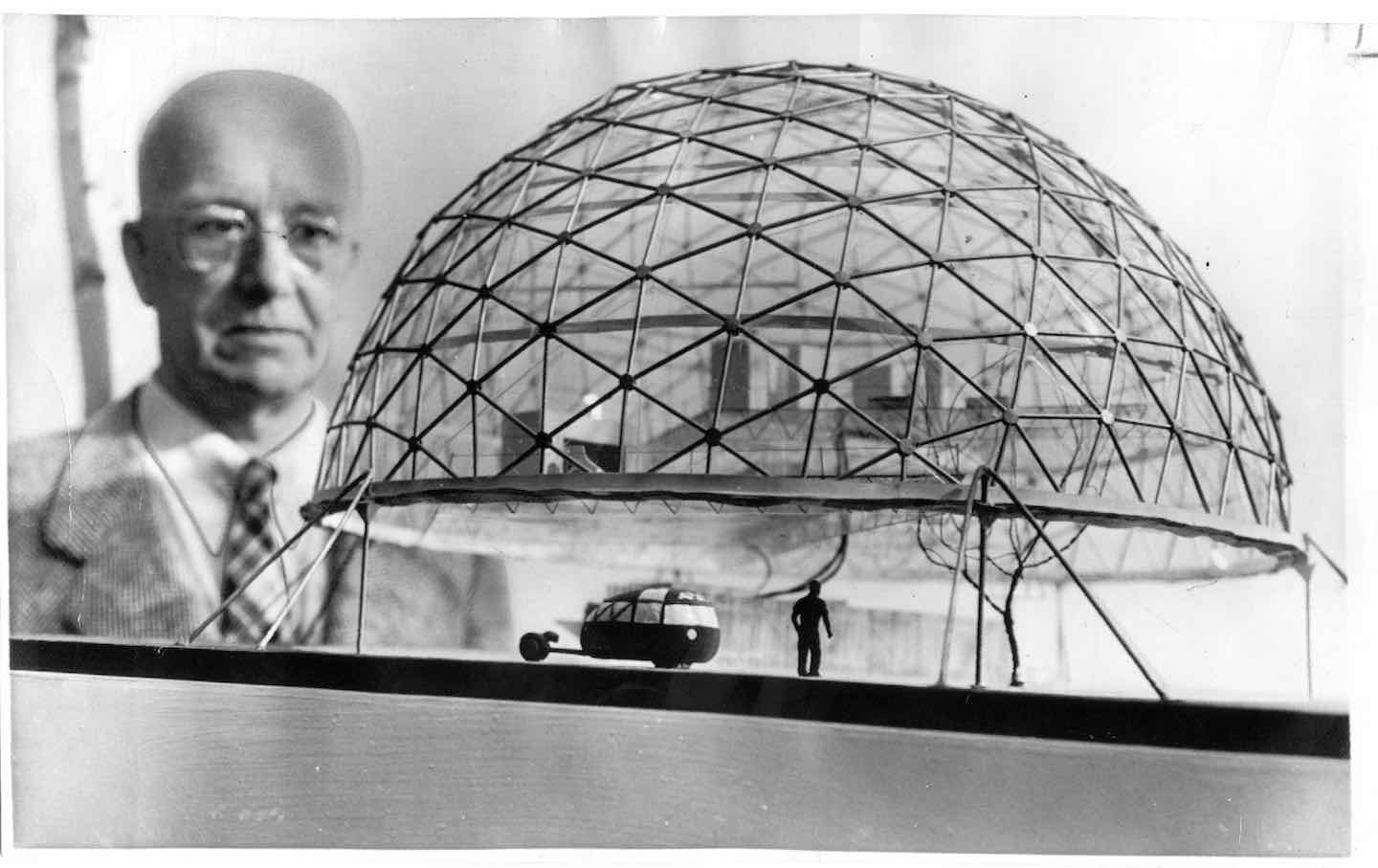

Buckminster Fuller, 1978. (Photo by Frank Lennon/Toronto Star via Getty Images)

Across the St. Lawrence River from downtown Montreal, an ethereal and monumental sphere can be seen rising from the sloping topography of St. Helen’s Island. Originally completed as the US pavilion for the International and Universal Exposition held there in 1967, the design of this geodesic dome has been recognized for decades as the crowning achievement of R. Buckminster Fuller. The dome embodies several of the mathematical principles expounded by the architect and theorist during his lifetime. Its structure is based on the 20-sided icosahedron, an ancient geometric figure that Fuller obsessed over and derived from the close packing of spheres. Having built relatively few buildings during his career compared to architects of similar stature, Fuller established his reputation instead through lectures, publications, and academic studios. He was infamous for speaking hours on end and speculating well beyond building construction in his elaborate attempts to link the underlying patterns of society, technology, and nature. His more than 25 patents and multiple honors were only eclipsed by his status in popular culture: A January 1964 cover of Time depicted Fuller’s head as a geodesic structure surrounded by many of his futuristic inventions, with the article referring to him as the “greatest living genius of industrial-technical realization in building.”

Fuller is the subject of a new biography by Alec Nevala-Lee, titled Inventor of the Future: The Visionary Life of Buckminster Fuller. It is the author’s second foray into biography, following 2018’s Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction. The new book is a natural extension of Nevala-Lee’s interest in 20th-century science fiction and aims for an unsentimental treatment of a lauded intellectual’s life that underscores the potential complications to Fuller’s legacy. As Inventor of the Future reveals, “Bucky” had a penchant for claiming sole authorship over projects within his orbit, even when they were largely realized through the diligent labor and intellectual rigor of others. Expo 67’s great dome turns out to be a perfect example: The project ruined Fuller’s relationship with the architect Peter Chermayeff, who claimed that while “it was a great privilege for all of us to do this magnificent project with” Fuller, “his monumental ego led him to over and over again beat his drum, distort the facts, take all the credit, and ignore many others who played major roles in the work.”

Though Fuller had achieved global prominence by the 1960s, the book highlights many of the personal and professional struggles that plagued him earlier in his life. He was born in Milton, Mass., in 1895 to a prominent family that included his great-aunt Margaret Fuller, the noted author, critic, and women’s rights activist associated with the Transcendentalist movement. He attended Harvard College but was expelled twice and never completed a degree. Instead, Fuller cut his teeth working odd jobs in his 20s, including at a textile mill and a meatpacking plant. He earned a machinist certification working with sheet metal, which surely nourished his nascent fascination with industrial fabrication. He was an erstwhile explorer too, traversing the landscape of Bear Island in Maine, where his family owned a summer home. It became a childhood tradition that would remain with Fuller throughout much of his adult life.

Some of the most fascinating narrative threads of the biography are found in the descriptions of Fuller’s personal relationships, which were often fraught with complications. This is most evident in his nearly 66-year marriage to Anne Hewlett, whom he met in 1916 while working as a cashier and accountant for a meat-packer in Brooklyn. Anne lived in the upscale neighborhood of Columbia Heights with her parents and nine younger siblings. A creative spirit in her own right, she attended the innovative New York School of Applied Design for Women and later designed an attractive clapboard cottage for her family in Noroton, Conn., in the mid-1930s. This apparently gave her bragging rights over Bucky, who had not managed to realize his dream of building an affordable model home using industrial technologies by then, despite several attempts that ended in financial losses for the family. As Nevala-Lee highlights throughout the book, Fuller was a serial philanderer, though he remained married to Hewlett until the end of both their lives in 1983. (He apparently willed himself into a fatal cardiac arrest while she lay unconscious in a hospital out of fear that she was “worried to go” without him.)

Shortly after his marriage to Anne, Fuller joined the US Navy during the First World War and in 1917 commanded a rescue ship named the Wego that patrolled Bar Harbor and Frenchman’s Bay looking for German U-boats. After being transferred to a base in Norfolk, Va., a year later, he took an opportunity to complete a Naval Academy program in Annapolis, Md., that appealed to his desire for a generalist education. Fuller enjoyed his time in the military, which provided circumstances that he eagerly mythologized for the rest of his life. He claimed to have been present for the first transoceanic telephone call made by President Woodrow Wilson and to have invented a “seaplane rescue mast and boom” that saved “hundreds of pilots’ lives.” Unsurprisingly, Nevalee-Lee was unable to find a single credible source to back up either story.

It turns out that Fuller’s innate capacity for exaggeration was both a hallmark of his vivid imagination and a long-standing ethical inadequacy. Fueled by a generalist sensibility, his ideas tended to flow across disciplines, from the sciences and mathematics to the humanities, the social sciences, design, and entrepreneurship as well. This gave him a reputation early on for being a jack of all trades but master of none. The notable exception, perhaps, was his knack for self-promotion, which was well suited to the thing that Fuller enjoyed doing above all else: inventing. The early years of his career after World War I are marked by the constant ups and downs of his proposals for industrial inventions and business models, many of which failed or disappeared into obscurity. One of his earliest ventures led to the patent of a unique brick made from compressed wood fibers that formed the modular unit of the Stockade Building System. Stockade was a joint venture between Fuller and his father-in-law, the architect James Monroe Hewlett, who provided funding and consultation until the company flopped in 1927. As was often the case with Fuller’s investors, Hewlett never recovered his initial investment or garnered any real credit for his involvement.

Outside of family, Fuller surrounded himself with interesting designers and artists throughout his life. The biography sheds light on his close and long-lasting friendship with the Japanese American sculptor Isamu Noguchi. Collaborators on multiple projects, the two were roommates for a while in New York City after meeting in 1929 at the infamous café and bohemian haunt owned by Romany Marie in Greenwich Village. Renowned industrial designer George Nelson was another supporter of Fuller’s early in his career, offering him studio space at his offices after the two met through Noguchi, who eventually worked under Nelson’s direction at the Herman Miller furniture company. Yet some of the noted architects in Fuller’s circle early on were less receptive to his ideas and demeanor. Philip Johnson, for instance, once wrote that “Bucky Fuller was no architect, and he kept pretending he was.” While Frank Lloyd Wright maintained amicable relations with Fuller, he remained skeptical of his push for mass-produced housing.

Architecture only ever occupied a fraction of Fuller’s attention. In fact, he began to focus on transportation after the Stockade debacle and produced a prototype of the Dymaxion automobile in 1933, whose sculptural form was almost certainly indebted to Noguchi’s influence. The name is one of many coined by Fuller throughout his career, a portmanteau of the words “dynamic,” “maximum,” and “tension.” Designed with an ovoid shape to reduce wind resistance, the car’s futuristic body was to be built with lacquered aluminum. It had two fixed wheels at the front and a single wheel centered at the rear used for steering. Fuller claimed it was the first streamlined automobile in history, which the author points out is simply not true, and he apparently boasted to potential inventors that the first prototype had been driven for over 100,000 miles, when in fact it had not yet been built. The story ends in tragedy when a fatal crash in Chicago involving the first Dymaxion prototype took the life of its driver and severely injured two passengers. Fuller refused to acknowledge that flaws in the design had caused the crash and never credited any of his investors or admitted to any failures of the project.

Hubris is a constant theme in Nevala-Lee’s portrait of Fuller. Though this trait was detrimental to his personal and business relationships, it was key to sustaining the intriguing evolution of his thought. Fuller was a prolific and sometimes puzzling writer who leveraged his publications as a space for experimentation. Untethered to the contingencies of funding and feasibility that often grounded his material projects, his written works benefitted from the limitless possibilities of a still unknown future. The importance of speculative writing and graphic design became evident for Fuller as early as 1930, when he assumed a chief editorial role at the Philadelphia-based magazine T-Square and transformed it into the rogue publication Shelter. It served as a forum to disseminate his early ideas about affordable industrialized housing, and his writing supposedly attracted the attention of James Joyce (at least according to an account from one of Fuller’s friends, the Irish writer George William Russell). He also began to evangelize about the geodesic dome, the building type most associated with his legacy, which he believed was the ultimate solution to the need for universal housing. A sphere encloses the maximum amount of space with the minimum amount of surface; thus it was a form that naturally embodied Fuller’s philosophy of “doing more with less.” In a stark and futuristic rendering by his longtime collaborator Shoji Sadao, Fuller even proposed a dome three kilometers in diameter in 1960 to create a controlled environment around most of midtown Manhattan.

In one of his earliest books, Nine Chains to the Moon (1938), Fuller outlined a very subjective history of technological invention—including his own version of a “scientific dwelling machine”—and first laid out his theory of “ephemeralization.” He coined the term to describe the natural tendency of technology to produce more with less, thus logically leading to a state of near-total dematerialization in the future. Though filled with jargon, the book demonstrated Fuller’s capacity to conjure far-reaching social philosophies by speculating on the implications of an increasingly industrial and technological world. Nine Chains was, according to its author, an attempt to “streamline society itself, encouraging mankind to move in the direction of least resistance.”

Living as we are amid the specter of endless automation, digital algorithms that circulate through and facilitate much of daily life, and the emergence of a virtual metaverse, Fuller’s prophecy has only become more eerie. His later books, such as Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (1968), Synergetics: Explorations in the Geometry of Thinking (1975), and Critical Path (1981), would become cult classics among the generation of free-thinking libertarians and early Silicon Valley boosters who subscribed to the ethos of the Whole Earth Catalog. As discussed in Nevala-Lee’s introduction, the influence of Fuller’s ideas were particularly impactful for the young generation of inventive entrepreneurs who would form America’s tech industry, including Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak.

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation

Fuller’s reach as an educator and speaker is also discussed at length in the book. Nevala-Lee essentially credits Fuller’s approach to teaching design studios as the origin of the think tank model eventually popularized by tech start-up culture. Of note are a series of courses taught by Fuller at Black Mountain College in North Carolina in 1948 and ’49. The school’s experimental and multidisciplinary curriculum was influenced by the legacy of the Bauhaus and attracted avant-garde faculty, such as the painter and former Bauhaus instructor Josef Albers and his partner, prominent textile artist Anni Albers. Fuller met choreographer Merce Cunningham and composer John Cage at Black Mountain, who influenced his idea of the architect as a “comprehensive designer” working across multiple scales, platforms, and mediums. Under Fuller’s direction, students successfully constructed the first large-scale geodesic dome from lightweight materials. He shamelessly stole ideas from talented students too: Fuller claimed for decades that he invented the principles of “tensegrity,” which was another specialized term he coined to describe structural systems of isolated components under compression held within a matrix of continuous tension. In reality, he observed and copied this idea from the work of then-student Kenneth Snelson, who went on to have a successful career in his own right as a sculptor. Yet Snelson never fully forgave his mentor for claiming authorship of his discovery.

Today, many disciplines, including architecture and the fine arts, are beginning to reexamine the dominance of canonical figures who are overwhelmingly white and male and who embody the myth of the solitary genius. In this context, I must admit that my first reaction to the release of a new book about Fuller was less than enthusiastic. Nonetheless, Inventor of the Future is a welcome reassessment of Fuller’s contributions to design, science, and mathematics that adeptly frames the merits and failings of his approach and life’s work—whether it was inspiring today’s insipid tech leaders or forcing us to question the slippery bounds of intellectual property and authorship. As Fuller once said: “When you can’t find the logical way, take the most absurd way.” Nevala-Lee proves that Buckminster Fuller certainly lived up to his own words.

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated the ubiquity of one of Buckminister Fuller’s statements.

Daniel Luis MartinezDaniel Luis Martinez is an architectural designer, educator, and co-founder of LAA Office: a multi-disciplinary design studio that explores the intersection of landscape, art, and architecture.