The Crisis in the Care Economy

How was care commodified? And what has that meant for an undervalued but increasingly important workforce.

At the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893, visitors crowded outside a small, white clapboard house with a peaked roof and a wide front porch. Inside was a kitchen, outfitted with a slow-cooking oven, a gas table, and other innovations designed to produce maximally nutritious meals with minimal fuel. Over the course of two months, the kitchen—staffed by experts trained in the science of food preparation—fed 10,000 visitors low-cost, calorie-dense meals: Boston baked beans, pea soup, beef broth, and escalloped fish. Despite its outwardly domestic appearance, the clapboard house was a public kitchen, open to all: The MIT chemist Ellen Swallow Richards imagined that activists might set up such establishments in working-class neighborhoods, serving inexpensive meals to the families of wage-earning women who didn’t have time to cook.

Books in review

-

When You Care: The Unexpected Magic of Caring for Others

Buy this book -

The Last Human Job: The Work of Connecting in a Disconnected World

Buy this book

To Richards and other “material feminists” of her era, writes the historian Dolores Hayden, public kitchens and other forms of collective housekeeping solved two related problems: the overwork of women and the undernourishment of the nation’s poor. At the turn of the 20th century, new technologies had facilitated a shift from the production of goods in households to their mass manufacture in factories. But the work of cooking, cleaning, and childcare remained largely confined to the home, understood not as labor that might contribute to social and economic progress but as the innate functions that women always performed. The remedy to the naturalization of both women’s work and household poverty, the material feminists believed, was technology that would usher essential services out of the home and into the modern industrial world. If household work could be industrialized, it could, many of them believed, ultimately be socialized as well.

Richards’s vision did not come to pass. In the early 20th century, new household technologies such as vacuum cleaners and washing machines promised to lighten housewives’ loads—but they also raised standards for cleanliness as well as women’s emotional investment in homemaking. These new tools of domestic efficiency created “more work for mother,” as Ruth Schwartz Cowan has argued, and more work for the mostly Black and immigrant household workers that some homemakers paid. In the second half of the century, women increasingly resisted the obligations of paid and unpaid domestic labor and fought their way into work outside the household. As they did so, commercial establishments—sometimes buttressed by public spending—emerged to meet demands for the work that women had once performed at home. The number of childcare centers tripled between 1967 and 1990. Hospitals are the largest employers in many states. More than 1 million elderly Americans reside in nursing homes. More recently, these establishments have also sent care labor back into the private home: Agency-hired health aides, cleaners, and nannies—most of them still Black and immigrant women—constitute the new domestic labor force.

Through all of these changes, the care economy has remained structured by an ever-increasing wealth gap: Workers put in long hours for low wages, and yet adequate care remains unaffordable for many who need it. The Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated these pressures, spurring many already overtaxed workers in deliberately understaffed establishments, from hospitals to schools, to go on strike or find other employment. We have called this phenomenon “the care crisis.” Now, many of the same establishments that created this crisis are promising to remedy it with more technology, introducing applications of artificial intelligence that policymakers and companies say will reduce costs and workloads.

How did we get here, and what are we to do? Two new books offer diagnoses of the care crisis that shed light on how feminists’ dream of emancipation from the unequal burdens of housework gave way to the commodification of care. The journalist Elissa Strauss’s When You Care: The Unexpected Magic of Caring argues that cultural narratives—including those of some feminists—have often discounted the value of intimate caregiving, economic and otherwise. The sociologist Allison Pugh’s The Last Human Job: The Work of Connecting in a Disconnected World offers a more materialist explanation. She shows how employers have long sought to standardize the interactive service work that she calls “connective labor,” degrading its quality and disempowering workers in the process.

Together, Strauss and Pugh make a compelling case for valuing care as a societal good and as skilled labor. Yet, even as care has moved into a modernizing commercial economy, the problems that the material feminists identified persist: Those who perform it are still overworked; those who need it are still underserved. So untenable did such inequality seem in the 19th century that feminists were sure a fundamental transformation was on the horizon. “There is wealth enough now to house the whole people in palaces,” one suffragist magazine predicted in 1871. “The Grand Domestic Revolution is going to take place.”

Strauss first wondered what it might mean to value care after she had her oldest son. As the mother of a young child, Strauss feared that caregiving would consume not only her time but also her identity: As a journalist, she warned women not to let motherhood “colonize their otherwise wild and interesting minds.” But as Strauss’s first son grew older and she had a second, she found that caregiving did not diminish her intellectual life but rather fueled new insights into economics, politics, and philosophy. Caregiving has been “a transcendent experience that has challenged me and enlightened me,” Strauss writes. “Why did nobody tell me it could be like this?”

The societal failure to take care seriously, Strauss observes, stems in part from a Western cultural narrative that associates wisdom and heroism with independence. But she also attributes her initial failure to appreciate care to what she sees as the limitations of feminism itself. Strauss’s genealogy of this tradition runs from Virginia Woolf’s novels of domestic confinement to Betty Friedan’s famous characterization of the American suburban home as a “comfortable concentration camp,” to Shulamith Firestone’s vision of a world in which the invention of a mechanical womb would eliminate the need for biological reproduction. As Strauss sees it, these widely divergent thinkers agreed that “care and women’s liberation were in opposition.”

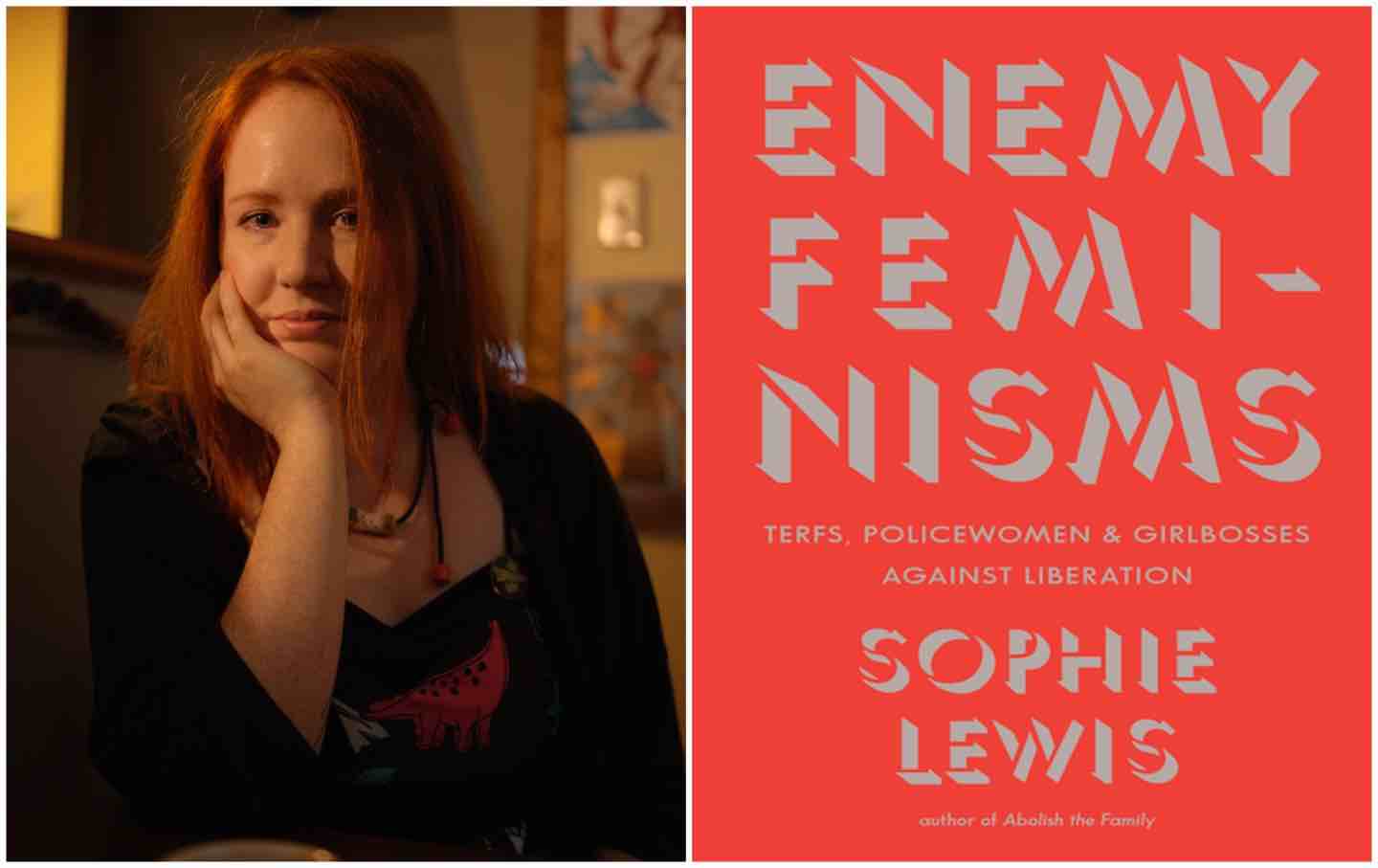

This is a somewhat oversimplified assertion. Firestone, for instance, aimed to eliminate the necessity of biological reproduction not because she hoped to eradicate care but because she hoped it would facilitate the inclusion of people of all genders and ages in the child-rearing process. The “cybernetic socialism” that Firestone imagined in her 1970 manifesto The Dialectic of Sex seemed even more fantastical than the World’s Columbian Exposition, but as the critic Sophie Lewis has written, Firestone had engaged in a serious study of experiments in communal living. In this, she was not alone among second-wave feminists. Even Friedan, as the historian Daniel Horowitz has noted, was a former labor journalist who toyed with the idea of communal living and wrote admiringly about a cooperative daycare in a housing project in Queens. In The Feminist Mystique, Friedan argued that work “serving a real purpose in the community”—not mere waged employment—was the key to psychological fulfillment. The feminism that Strauss really takes issue with, it seems, are Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In and other corporatized, pop-culture variants. “It was Woolf, Beauvoir, Friedan, Sandberg, Carrie, Miranda, Samantha, and Charlotte that I found the most convincing recipes for smashing the patriarchy and living a fuller, more complete, life,” she writes, the latter four names referring to the protagonists of Sex and the City.

Nevertheless, Strauss is right that many feminists, focused on the problem of care’s confinement to the private home, assumed that transformation would occur outside it. As she observes, Black and queer feminists, excluded from both the cultural narratives that valorized domesticity and the public policies that enforced it, were less likely to take this view. Strauss takes particular inspiration from Johnnie Tillmon, a leader of the National Welfare Rights Organization (NWRO), who fought against the imposition of work requirements on aid recipients. As Tillmon and other welfare activists argued, mothers on welfare were already performing essential work; the state simply refused to recognize their unpaid labor in the home as such. Strauss, situating herself within this tradition, writes movingly about the value of intimate care—not only its economic value to society but also its psychological, philosophical, and even spiritual value for those who perform it. She interviews, for instance, a philosopher whose care for her disabled daughter inspires her to research “care ethics,” and a formerly incarcerated man who learns to cope with his PTSD after becoming a father.

Strauss notes that characterizations of care work as inherently oppressive also overlook the perspectives of many paid care workers, who can find real meaning and purpose in their work. This is true, and yet care workers’ ethos of service can also be used to justify their exploitation. The historians Eileen Boris, Jennifer Klein, and Gabriel Winant have described how employers take advantage of the compassion of nurses and health aides for their patients in order to compel them to work punishing hours and extra shifts without pay. In the 2009 Supreme Court case Long Island Care at Home v. Evelyn Coke, which upheld the exclusion of home health aides from the Fair Labor Standards Act, Justice Stephen Breyer argued that requiring companies to pay aides for overtime work would mean depriving needy patients of necessary care. Perversely, declarations of care’s social importance can also function as assertions of entitlement to care workers’ commodified labor, at worst becoming, as the political theorist Ophelia Vedder argues, a kind of modern-day hand-wringing about the “the servant problem.”

The NWRO activists were well aware of these contradictions. As Boris has written, they characterized their workfare assignments as maids, nannies, and “child development associates” for wealthy white women as “slave jobs”—not because they didn’t value care, but because providing it for low wages under coercive conditions offered no intrinsic good. “Wages are the measure of dignity that society puts on a job,” Tillmon said in a 1972 newspaper interview about the NWRO’s work. “Wages. Nothing else. There is no dignity in starvation.” Strauss rightly emphasizes the necessity of better workplace protections, hours, and wages for care workers, but the obstacle to achieving these things is not merely a failure to see care as necessary for its recipients or meaningful to its providers. No one knows the value of care better than the bosses who extract profit from it.

Perhaps it’s no surprise, then, that even in Silicon Valley, Lean In feminism has gone out of style. Among contemporary “care feminists,” Strauss cites a number of tech-adjacent celebrity advocates like Eve Rodsky (the author of the best-selling book Fair Play, which gamifies the division of chores among couples), Reshma Saujani (who founded the Hollywood-endorsed “Moms F1rst” Initiative, which makes the “business case for child care”), and Amy Henderson (whose consulting company TendLab “helps companies unlock the power and potential of parents at work”). There’s nothing wrong with encouraging couples to divide up chores or urging companies to adopt family-friendly policies, but these programs seem as unlikely to help the majority of the paid-care workforce as invocations to women to assert themselves at home and at work.

While motherhood inspired Strauss to reevaluate her assumptions about care, Allison Pugh’s professional experience sparked her interest in what she calls “connective labor”: the interpersonal service work characteristic of (though not exclusive to) the care economy. Like Pugh’s highly regarded previous books, The Last Human Job draws on deep ethnographic research on intimate and sometimes painful topics. Effective sociological research, Pugh writes, requires a kind of empathic ability to understand and reflect another person’s emotions. Nurses, schoolteachers, hospital chaplains, and therapists (among others) similarly need to establish intimacy and trust to perform their jobs: “Connective labor,” for Pugh, represents a “layer of labor beneath the labor” recognized in their formal job descriptions.

Pugh’s concept of “connective labor” is clearly indebted to the sociologist Arlie Hochschild’s “emotional labor.” Though it’s often misappropriated to describe any effort that involves feeling, Hochschild originally coined the term to describe how low-waged, mostly female service workers induce or suppress their own emotions (such as the flight attendant who must smile at the airline’s passengers and knows her smile can’t look forced or strained). Emotional labor, Hochschild argued, results in an experience of profound alienation for the worker, who must dissemble the deepest parts of herself. But for Pugh, in contrast, connective labor generates a kind of recognition—at best, a mutual feeling of “seeing and being seen.”

The concept, Pugh is aware, could run the risk of sounding fuzzy or sentimental. She is careful to emphasize that the visceral feelings that effective connective labor inspires result from training, effort, and intentionality. Workers think carefully about even the small bodily gestures they deploy: Pugh describes how a schoolteacher instructs trainees to kneel down beside a student’s desk rather than approach them from behind. In one of the book’s most interesting scenes, a group of hospital chaplains perform a training exercise ahead of their shift in a neonatal care unit. The participants stand in a circle and toss a ball of yarn to one another, saying out loud what comes to mind when learning that someone they love will have a baby. Then the group’s leader asks each member of the group to drop the yarn and say how they would feel if the baby died. By imagining the unimaginable, the chaplains treat grief as a concrete process to study and manage, if not master.

Only a few years ago, a steady stream of corporate self-help articles characterized “emotional intelligence” as the critical skill set for 21st-century workers. The very notion of feminized labor as natural or innate—which has justified its undercompensation and underregulation—suddenly made it seem invulnerable to technological displacement. But as Pugh writes, employers themselves were never under any such illusion. Long before the development of AI, as she describes, private companies and policymakers applied the techniques of so-called productivity-maximizing management to care: If you have ever sat on an examination table while your doctor or nurse hunched over a computer filling out forms, then you have experienced one of the forms of “scripting” and “counting” that Pugh shows have eroded workers’ autonomy, increased their workloads, and worsened the quality of the services they provide.

The irony is that the more such standardized systems degrade the quality of connective labor and intensify workloads, the more technology seems like an appealing solution. So it’s no surprise that the very jobs in healthcare and education only recently held out as immune to technological displacement now represent what Pugh calls “the automation frontier.” She offers the example of a diabetes care application pitched to hospitals as a means of relieving the burden of nurses burned out from rapidly processing patients through a scripted telehealth service. Artificial intelligence can’t replace meaningful interpersonal interactions, but when those interactions are made scarce, it seems like “better than nothing.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Pugh illustrates that standardization has harmed both the practitioners of connective labor and the recipients of their care. But the alternative she proposes is not entirely satisfying. In contrast to productivity-enhancing technologies, Pugh advocates for the development of organizations that prioritize relationships, creating what she calls a “high-touch” social architecture. Workers, she argues, need not only adequate compensation but also adequate time and attention to cultivate connections. Yet an excess of those things can also undermine workers’ autonomy. Earlier in the book, Pugh acknowledges that connective labor can also function as a form of domination. She describes the experience of Betty Sinclair, a Guyanese immigrant who works as a home health aide for elderly clients on New York’s Upper East Side. Sinclair struggles with a patient whose wife treats her poorly, until—realizing that the wife feels neglected—she cooks her a meal. The woman, Pugh writes, seems to have felt entitled to deference from Sinclair, a low-income woman of color working in her home. Able to assess the complex dynamic involved, Sinclair could effectively treat her patient—but she also felt compelled to perform a personal service outside of her contractual obligations.

Pugh is aware that the opposite of systematized connective labor can look like a kind of service on demand: personal coaching, concierge medicine, and cultivated leisure “experiences.” She argues, rightly, that attentive care need not be a luxury for the wealthy. But on the flip side of connective labor in a context of social inequality are workers like Sinclair—who, because of economic need, may not have the ability to refuse the intimacy that, as Pugh recognizes, can be coercive, too. For such workers, the relationship-oriented worksite may contain its own hazards.

Many material feminists recognized that the public kitchen, if established, might take a different form than the one displayed at the World’s Columbian Exposition. “The business organizations of men, which have taken so many industrial employments from the home, wait to seize those remaining,” Mary Livermore warned in 1886. “The saving in money will not accrue to the housekeeper, but to the outside business world.” Livermore urged feminists to form their cooperative kitchens, day cares, and laundries quickly—if they didn’t, the capitalists would get there first.

Unfortunately, it was Livermore’s fear, not Richards’s dream, that came true: Technology did not emancipate those who cook, clean, care, or connect. As Strauss shows, feminists focused on the problem of women’s confinement to the home were overly optimistic that freedom might lie in the world outside it, and so missed an opportunity to articulate the value of intimate caregiving itself. Indeed, as Pugh demonstrates, the standardization of interpersonal, emotional labor in the paid workforce undermines both workers’ autonomy and the quality of the work they perform.

And yet, just as capitalism co-opted feminists’ visions of emancipation from household drudgery, it can also co-opt our rightful insistence on our work’s worth. Bosses, policymakers, and simple economic necessity can transform workers’ dedication to their patients and clients into demands for more work, longer hours, and lower pay; the balance can tip from care to compulsion. In this way, the politics of care can move between a kind of Scylla and Charybdis: the Scylla of industrial efficiency and the Charybdis of personal service; the Scylla of mechanization and the Charybdis of naturalization.

Is there a way out of this trap? Among the feminists who searched for one in the 1970s were the autonomous Marxist feminists who founded the Wages for Housework movement. In contrast to the material feminists, these activists didn’t hope to industrialize care. The household, they argued, was already a “social factory,” and its principal commodity was the male worker himself. Women’s unpaid work subsidized men’s wages, sustaining the productive sphere that only appeared separate from the home. For that reason, they rejected the idea that women’s emancipation would come from working outside the home, which only meant trading “slavery to a kitchen sink” for “slavery to an assembly line.” Instead, inspired by the welfare rights movement, they demanded remuneration for the work that women already performed.

Yet demanding a wage for housework did not mean celebrating it: The point was ultimately to make housework a form of labor that one could refuse. As the feminist theorist Kathi Weeks has written, the movement’s goal was to address both the devaluation of housework as work and its overvaluation as love. Insisting on the value of care meant insisting on our right not to perform it. For the movement’s founder, Silvia Federici, such a refusal carried with it the utopian conviction that we might create new possibilities for care’s flourishing—possibilities outside of either the household or the commercial establishment. “We want to call work what is work so that eventually we might rediscover what is love and create what will be our sexuality which we have never known,” she wrote. The Grand Domestic Revolution, she thought, might still come.

Support independent journalism that exposes oligarchs and profiteers

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation