It’s Life as I See It, a recent anthology of work by Chicago-based Black comic artists from 1940 to 1980, takes its name from a cartoon by Charles Johnson, which shows a Black artist standing with an older white man in front of a large canvas. The canvas is painted black and surrounded by a thick white border. In the caption, the artist informs the other man that the painting is life as he sees it.

Many of Johnson’s comics are similarly blunt. They are usually single panels that provide pointed commentary about racism and the struggles of Black people in a society that restricts and constrains their lives as much as the black painting is by its white border. Johnson only needs one panel and a few words to capture the absurdity of the violence within whiteness and the laughable ignorance of supposedly well-meaning white liberals.

Johnson, who grew up in Evanston, Ill., told the Chicago Tribune in 1970, “Every man, I imagine, must entertain some cherished dream to which he devotes a great deal of his energies. After stumbling onto the market of racial humor reflected in the cartoons, mine has been to develop this area to its fullest.” He was inspired to focus on racial humor after attending a lecture by Amiri Baraka, the poet, novelist, essayist, music critic, and advocate of the Black Arts Movement who criticized the civil rights movement for its pacifist and integrationist politics.

The first of Johnson’s cartoons featured in It’s Life as I See It shows two Black men on a bench, with one asking the other, “Well, have we been a credit to our race today?” Another is of a Black man speaking on the phone while surrounded by a sea of white men at a party; he tells the person he is talking to that they can find him easily enough, since he’s the only one there wearing a corsage. With single panels and mostly single sentences, Johnson illuminates and mocks the absurdity of race relations in liberal America—where faux compassion and good intentions do little to address long-standing inequities.

Another artist in the anthology who shares Johnson’s wit, sharpness, and frustration with the microaggressions of racism is Tom Floyd. Born and raised in Gary, Ind., Floyd freelanced for The Chicago Defender while working for an industrial company in the city. When he was young, he wanted to start a superhero universe and took his portfolio to Stan Lee, the late creative lead for Marvel Comics, to pitch him on a proud, strong, Black superhero. Lee turned him down. Soon after, Marvel released Luke Cage, Hero for Hire, a character that Floyd saw as a bastardized version of his idea.

In 1969 Floyd published Integration Is a Bitch!, a book filled with illustrations inspired by his experiences as a college-educated Black man after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The racial tensions that Floyd’s comics explored were mostly situated and heightened in professional workplaces, likely the only place where many bourgeois white people—who wanted to show how tolerant they were after integration—actually encountered Black people as near-equals.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

In the first comic from Floyd’s book that appears in It’s Life as I See It, a white manager at an engineering firm (with a copy of the Civil Rights Act on his desk) tells an underling, “Hire some Negroes… Quick!” In another, a manager addresses a group of clapping spectators while singling out a Black employee sitting at his desk, saying, “And this is our Negro!” In a third, a Black employee listens to a white female coworker as she tells him, “We had a nice colored man cutting our grass yesterday…and you know… He didn’t steal a thing…”

Johnson and Floyd are two examples of the wonderful humor, wit, imagination, and insight that fill the anthology, and they also represent its central frustration. The comics are constantly gesturing to, rebelling against, and ultimately being shaped by the conditions of white supremacy and domination. Even at their funniest, there’s a visible exasperation and coping by humor within these cartoons.

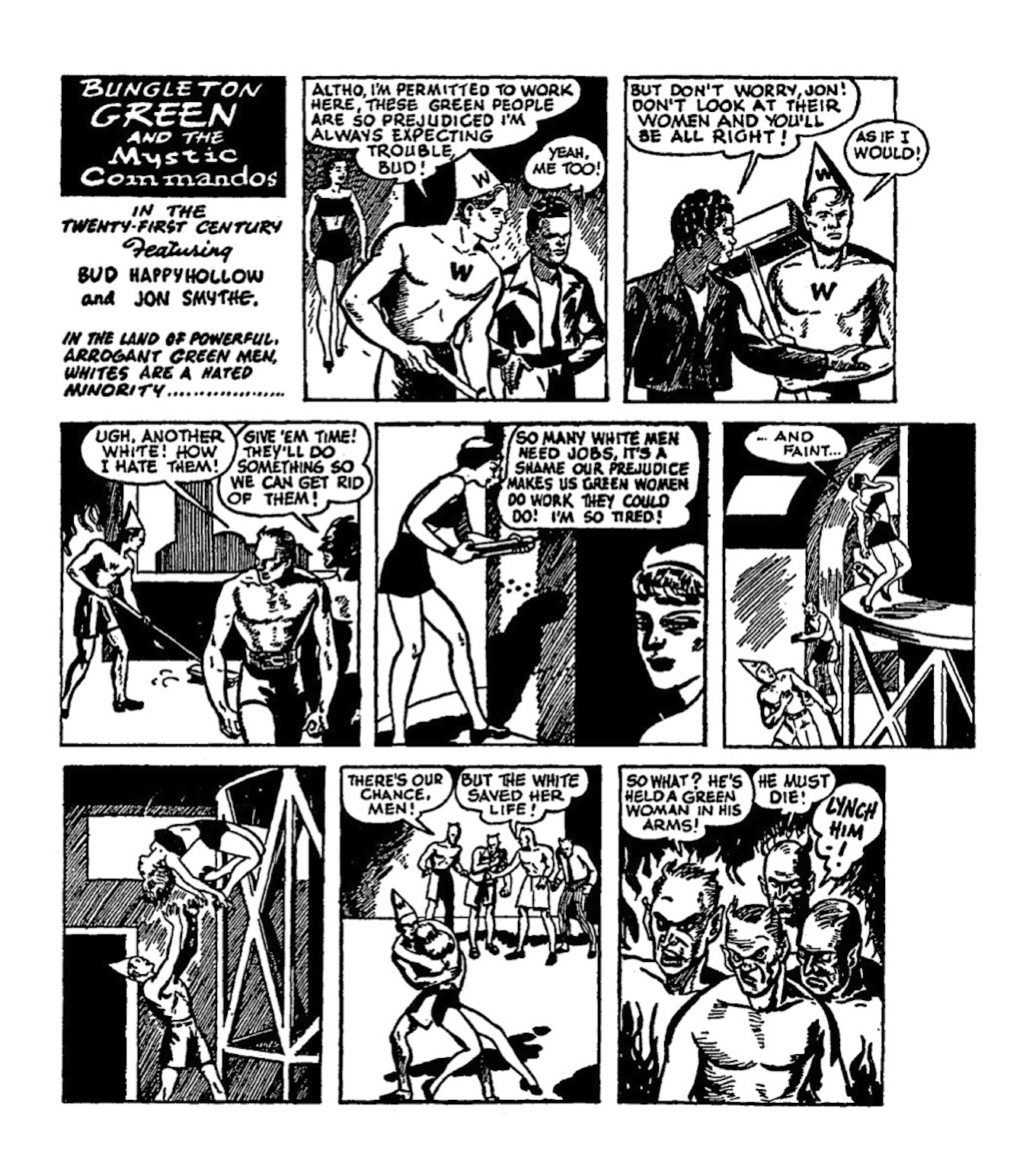

The longest work in the anthology belongs to Jay Jackson, who worked at the Defender and helmed a run on the Bungleton Green comic strip, which was created by Leslie Rogers in 1920 and ran in the Defender until 1968. The longest-running Black comic character to date, Bungleton Green started off as a vagrant in a top hat, then became a self-made millionaire, and then went back to being a vagrant before he became the mentor to a group of kids called the Mystic Commandos. Jackson began his work on the strip in 1936 and turned it into a science fiction story focused mainly on the group’s adventures.

Set in the year 2044, Jackson’s Bungleton Green takes place in an alternate future where complete equality exists in America. Yet there’s a new world populated by green humanoids who are racist against white people. The president of the United States sends Lotta, the Black mayor of Memphis, and Jon Smythe, a white man, to the land of the green people to teach them about democracy and equality. There, Jon encounters Bud Happyhollow, a Mystic Commando from the past, who tries to help him with his mission.

Throughout the comic’s story, Jon is continuously discriminated against. He is barred from establishments and belittled in public. The other white people that he meets are either just as mistreated as he is or believe that they deserve the mistreatment because of the bad behavior of a few white individuals.

Jon continuously asks why the green people don’t like the white ones, and even though he’s told that the green people are just imitating the behavior of white people from the past, he finds the treatment so absurd that he refuses to leave until he’s resolved the problem. He eventually does: After failing to convince the green people of the goodness of the white ones through rhetoric, Jon incites a race riot. As the green government threatens to hunt down white people and destroy their few neighborhoods in reaction, the US government uses its military power to force the green people into granting full equality to whites. After equality is established, several green people are shown regretting their former behavior.

In the end, the green people change their racist behavior rather quickly and don’t even seem to know why they were so hateful to begin with. It’s a happy and hopeful ending that relies on the assumption that appealing to reason can break the spell of bigotry. That makes it an unsatisfying conclusion, one Jackson may or may not have intended, because it’s an appeal to a shared polity that exists only superficially or in exceptional instances in a system built upon racial inequality.

What is tragic about the comics of Jackson, Johnson, Floyd, and most of the other artists in It’s Life as I See It is captured by Johnson’s titular panel. Regardless of how funny the comics are, how persistently true they remain, or how ambitious they try to be, there still remains that solid white border that hems in the kinds of worlds they can imagine, as well as limiting the artistic and financial possibilities of Black artists in those times.

Among the publishers of Black comic artists in Chicago were the aforementioned Chicago Defender, founded by Robert Sengstacke Abbott in 1905 to serve the growing Black population on the South Side, and Johnson Publishing, which was launched in 1942 with Negro Digest, followed eventually by Ebony and Jet. These outlets didn’t match the reach of their white counterparts like the Chicago Tribune, nor could they provide a stable living for the artists, but they gave Black artists a space to depict themselves and to explore the reality of Black life, in Chicago and the larger world, in their own way.

The power of the white border is felt throughout the anthology, even if it is mostly gestured at or kept on the margins. The comics address and poke fun at the different levels of racial violence, from the degradations of a racist workplace to the real riots and lynchings that were used to terrorize Black people. The artists themselves were mostly blocked from mainstream publications, and even when they were allowed into those spaces, it was to do the remedial work of explaining who Black people are to a white audience, as if Black people were as alien as the green people.

What the white border does is dominate. This domination is the critical element that the Mystic Commandos comic misses with its happy ending in which the green people suddenly become accepting of their white counterparts. Or maybe such an obvious and cruel reality can’t be openly stated, as it denies the very possibility of a happy ending. The border is the domination of a system of rank inequality, something that is not a question of feelings or reason. It not only frames the lives of those made marginal; it also invades their art and imagination, as they’re forced to constantly grapple with the struggle within it and mock its absurdity—because it is ridiculous, and laughing at the ridiculous is a way to get through to the next day.

Yet the existence of this anthology—regardless of the violence that surrounds so much of the work, and, in a way, because of that violence—is a gift. It is part of the history of Black creativity and struggle through art. It is a testament to the talent of Black artists and a statement that they have been working in creative ways to tell their stories and fight against the demeaning depictions of Black people in mainstream culture. This collection of almost-forgotten and sometimes short-lived comics is a powerful work, one that showcases resistance to domination and stands as a celebration of the ability of Black people, then and now, to find humor in that white border and, as a consequence, to gesture to its possible end.