Christina Ramberg’s Public Secrets

A look at the life and work of one Chicago’s great 20th-century painters.

Christina Ramberg. Untitled (Hand), 1971.

(Courtesy of Karen Lennox Gallery, Chicago, and the Estate of Christina Ramberg / Photo by Jamie Stukenberg)

“Chicago’s art history remains a closely guarded secret,” wrote the cultural historian Neil Harris back in 1990. Among the city’s secrets is the work of Christina Ramberg. Since her death nearly 30 years ago, she’s been known mainly for not being as well-known as she should be. But that might be about to change. An exquisite retrospective of her work, beautifully curated by Thea Liberty Nichols and Mark Pascale, at the Art Institute of Chicago, through August 11—which will then tour the country, traveling to the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art—will bring her paintings to a wider audience.

Ramberg was part of a remarkable cluster of artists who began exhibiting in the Windy City in the mid- to late 1960s and whose work was shown at the city’s Museum of Contemporary Art in 1972 under the rubric “Chicago Imagist Art.” The name stuck—to the discomfort of some of the artists, who, like most artists, were averse to being categorized. Still, they did have a lot in common. Most were graduates of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), where they were mentored by Ray Yoshida, a Hawaiian-born painter only a little older than they were. Yoshida (another of Chicago’s well-kept secrets) was fascinated by art from beyond the mainstream—not only the art of non-Western cultures, but of self-taught “outsiders” such as Chicagoans Lee Godie and Joseph Yoakum, whom Yoshida, Ramberg, and their friends got to know—and yet, as the critic Ken Johnson observed, “Modernist sophistication shows in his refined play with flattened forms, rich color and eye-buzzing patterns,” in paintings that often seemed to hover in a no-man’s-land between abstraction and representation.

Another mentor at SAIC was the art historian Whitney Halstead. Like Yoshida, Halstead had an eye for art outside the European canon, and he encouraged his students to explore the Field Museum (Chicago’s museum of natural history) as well as what was then called the Oriental Institute (now the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures, West Asia & North Africa) at the University of Chicago. Yoshida’s and Whitney’s students formed tight-knit circles with shared passions and interests and an independent streak that resisted the biases and predilections of the art-world authorities. Populated with artists who encouraged one another’s exploratory propensities, it might have been a small world, but not a claustrophobic one. Somehow it’s telling that, whereas earlier generations of artists starting out in Chicago mostly had to leave to find their way forward (think of Leon Golub, June Leaf, Claes Oldenburg, Nancy Spero), the Imagists—let’s accept the name—were able to thrive there.

Beyond the Art Institute, these young artists soon found a new supporter in Don Baum, a somewhat older artist who was organizing exhibitions at the nonprofit Hyde Park Art Center on Chicago’s South Side, far from the city’s central Loop, where the commercial galleries were. In 1966, he mounted a show of six artists—James Falconer, Art Green, Gladys Nilsson, Jim Nutt, Suellen Rocca, and Karl Wirsum—under the sardonic title “Hairy Who?” (The story has it that the name came when the artists were discussing a local art critic, Harry Bouras, and Wirsum asked, “Harry who? Who is this guy?”) Their work, as distant from any kind of naturalism or realism as it was from abstraction, tended to be confrontational, even vulgar in its imagery, linear in structure but popping with color, at times reminiscent of the underground comix and psychedelic posters of the era, but infused with an obsessiveness evocative of outsider art—and with fastidiously controlled technique. The six artists exhibited twice more at the Hyde Park Art Center in the next few years and then more widely; meanwhile, Baum continued organizing shows of other artists of similar bent under the hallucinogenic-sounding titles “Nonplussed Some” and “False Image,” both in 1968. It was in the latter show that Ramberg made her exhibition debut, and she followed it with an appearance the next year at a Baum-organized exhibition at a bigger and more prestigious venue, Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art, “Don Baum Says: ‘Chicago Needs Famous Artists.’”

Ramberg was just 22 and a newly minted BFA when her work appeared in “False Image,” but she’d already found a style, and it was recognizably related to the Imagist sensibility that had been developed by the Hairy Who group (whose senior member, Nutt, turned all of 30 that year). But it had a distinctive and very personal twist. Like most of her fellow Chicagoans, Ramberg had developed an approach that ceded the initiative to line, to drawing, and that conjured all sorts of vernacular pictorial styles, from comics to amateur sign-painting to illustrated newspaper and magazine ads. The others filled their tightly constructed compositions with brash color and packed them with incident, almost to the point of horror vacui. Ramberg, by contrast, cultivated a deceptively sober palette dominated by a surprisingly extensive range of browns, beiges, olives, grays, and black—tones that are cool, moody, mysterious, introverted, a bit nostalgic—and tended to place a single dominating form against a neutral background: an object of contemplation, an icon.

This sense of pensive inwardness, of subjectivity, plays in an interesting way against the blunt but unsettling bent of Ramberg’s lexicon of images: She mostly depicts fragmented, faceless female bodies and apparel, synecdoches and metonyms for “female”—part-objects, as a psychoanalyst might say. Typical of Ramberg’s early work is Hair (1968), a set of 16 small paintings, each showing the back of a woman’s head being stroked or patted or otherwise manipulated by a disembodied, seemingly feminine hand—in one case, by two hands. All we really see of this woman (assuming it is always the same anonymous figure) is her hair, done up in various ways from panel to panel, and a bit of her neck. Are the hands the woman’s own—is she primping? Or might it be someone else: a friend or even a lover? The viewer is left on the outside of all such questions. The paintings evoke ideas of touching and being touched, but abstracted from any definite origin, from any mark of personal identity.

They conjure the uncanny notion that one might look into the mirror and see not one’s face, but the back of one’s head—that one’s reflection might be looking away in the same direction. It sounds like an idea that might have occurred to René Magritte, and in fact did. The Belgian Surrealist might be Ramberg’s unacknowledged forebear: His 1937 painting La reproduction interdite (“Not to Be Reproduced”) shows the patron and poet Edward James gazing into a mirror that reflects the back of his head, resulting in a portrait that shows the same man twice but his face not at all. Another of Ramberg’s works, also from 1968, is called Cabbage Head. It plays a different sort of Surrealist joke on representation: One side of the head is covered, as usual, in tresses, but the other side is a cabbage. Rendered in crisp black and brown, the crinkly texture of the leafage might well be just another hairstyle; only the word distinguishes them. Magritte might have added: Ceci n’est pas un chou.

After the paintings of hands and hair, Ramberg systematically began adding selected elements to her image repertoire: shoes and corsets and other undergarments, usually with a vaguely old-fashioned look. Sometimes the corsets are worn by anonymous bodies, but often they just pose there against a nondescript background, as if animated by their own uncanny life force with no need for a wearer. From 1970 comes an eight-panel piece called Corsets/Urns. It’s like a catalog of items, each a variant of the others, and the only thing that distinguishes an urn from a corset here, as far as I can see, is that the urns must be the ones with the flat bottoms. Otherwise, they are all just flat, symmetrical shapes, strangely shaded in ways that recall the artist’s bright highlights on dark hair and isolated on identical olive backdrops. A journal entry clarifies Ramberg’s reason for equating the two kinds of objects: “Similar in shape and similar in function—they both hold and retain.” But isolating them as abstract forms and de-emphasizing their volume, she detaches them from their function. By this time, we might begin to wonder: Does it still make sense to call Ramberg an Imagist? Not much more than a word pulls these pictures out of the realm of abstraction.

What’s clear is that Ramberg was fascinated with certain charged objects and with her own ability, through the act of depiction, to transform them without losing their emotional valence. In the same journal entry, she speaks of wanting “to make from my obsessions and ideas the strongest, most coherent visual statement possible,” but professes bafflement that her fellow students (she was still in graduate school) seemed not to recognize the nature of her subject matter: “ideas about the fetish, masturbation, etc.” I’d guess, to the contrary, that they saw very well what sort of psychic material Ramberg’s work was dealing with and, for that very reason, preferred not to speak of it: They just didn’t want to go there.

In fact, that’s part of the beauty of Ramberg’s art: that it can be at once completely obvious and utterly ambiguous—that it contains a kind of silence and likewise allows viewers, and not only the students who were its first audience, to dwell in the unspoken. For that reason, I don’t think it’s quite right to say, as Art Institute director James Rondeau does in his foreword to the catalog, that Ramberg “conveys a pointedly feminist critique of the social conditions that shape and constrain women.” I would say, rather, that her art is aware not only of the general social conditions that, as she put it, “hold and retain,” but aware of itself as a vessel for feelings that are thereby contained yet also expressed—open secrets. The paintings don’t propose a critique, because they calmly accept the fetish—having one and being one—as a condition to be appraised and perhaps appreciated more than decried. As artist Riva Lehrer writes in the catalog, “The subject is both inside and outside herself, in a state of gendered double-consciousness.” Ramberg’s goal is not protest but a critical self-awareness.

In 1974, Ramberg painted some of her strangest part-objects, among them a pair of panels called Brunet’s Sleeves, which, if you grant the title any authority, might be lengths of gauzy black mesh fabric—fishnet or tulle—with hanks of hair worked into them; more likely some perverse form of stockings, but sure, they could be sleeves too. But more than anything else, they remind me of insect body parts seen under a microscope and recombined into symmetrical abstract structures. In any case, they are unattached to anything like a human body. Something similar is true of Tall Tickler and Taller Tickler, also both from 1974, apparently to be understood as sheathes for phalluses. (A French tickler is a condom with ribs and protrusions for that extra thrill.) The Ticklers are the first of very few evocations of male anatomy in Ramberg’s oeuvre. They were followed by a sequence of monstrous bodies without heads or hands—but like those empty corsets, they might be uninhabited costumes. And with those down-hanging sleeves or handless arms, they also resemble grotesque heads with horns or antennae. Here, Ramberg is playing with the ambiguity of her imagery, and the results are at once fascinating and repellant.

Ramberg continued on this path through the early 1980s, but then made a swerve: Starting in 1983, she took a break from painting and spent several years focused on quilt-making. It’s a surprise to see the quilts here, because they look like a completely different artist could have made them—not the one who made those odd and enigmatic paintings. One of the catalog’s contributors, Anna Katz, tries hard to show that painting and quilt-making were “parallel tracks” in Ramberg’s oeuvre, but this bears out mainly in the sense that parallel lines never meet. Katz herself quotes the artist, in a statement from 1989: “Quiltmaking bailed me out at a time when I had reached a crisis with my major interest—painting. I was dissatisfied with everything about my paintings and all my experiments were yielding nothing. Quiltmaking was the perfect activity for me at that moment because I did not have to think about content.” What, I wonder, began to bother Ramberg about content? Was she becoming uneasy about her grasp of it as her work kept getting more ambiguous, eluding any determinate image?

In any case, the quilts are a pleasure to see, but they were clearly more of a detour from her painting than an extension of it. A more substantial boost to our understanding of Ramberg’s art comes from the show’s extensive display of her archives of source material, notebooks, photographic slides, and objects. These not only evidence the intense visual curiosity she shared with most artists, but a specific methodology that suggests surprising connections with other artists of the time. Gathering clippings of a plethora of similar but nonidentical advertising images of wigs and hairdos, for example, or drawing multiple variations of bras, headgear, kimonos, and so on, seems already to have crystallized an artistic idea in advance of painting them: the archive as art. If Ramberg had thought of presenting these compilations to the public, she would have qualified for inclusion in the conceptual-art exhibitions that were taking place across North America and Europe at the time—for instance, the 1970 “Information” show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. That she did not do so hardly lessens the affinity. Later, when she saw Bern and Hilla Becher’s arrays of photographs documenting typologies of industrial architecture—the Bechers had notably been included in the “Information” show—she wrote in her diary that she “felt they were mine.”

We also see Ramberg’s passionate immersion in art history. One journal entry shows her exquisite copies of hand gestures found in works by the 18th-century Japanese artist Kitagawa Utamaro, with the written notation “lady holding pipe in one hand pushes up sleeve with the other. Lady counting on her fingers the days of her husbands absence has one hand thrust into sash from which handkerchief sized cloth emerges. Another lady with hand at neck with one finger hidden beneath fabric,” and so on. Her paintings of around 1971 are largely obsessed by such hands.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The paintings Ramberg made when she started painting again in 1986 were different in both form and content from her previous ones, but they had nothing to do with the conventional form of her quilts. There’s just one thing the late paintings have in common with the quilts, and that is the fact that, unlike all of her previous paintings, which were made on rigid panels, the new paintings were made on a textile support—canvas. And gone along with the hard Masonite supports she’d been using is the meticulous finish, the refined blending of brush marks that gave her work its cool, imperturbable gloss. Instead, the post-quilt paintings are loosely painted, with unkempt surfaces. And Ramberg’s previously subdued palette has been further reduced to a range of grays. Although the paintings are still symmetrical in composition, gone are the references to the human body or its accouterments. Swirling and rectilinear white or black lines on gray grounds conjure schematic, vessel-like structures seen at an angle from above. These untitled works seem to encapsulate a dialectic of structure and impulse. Lehrer suggests that, in these works, “Ramberg stepped away from—or rose above—the flesh, above fabrics, above the detritus of bodies altogether, though sexuality remains; the image of a womb penetrated by a shaft…seems to gesture toward sexuality as exaltation, the union of the forces of desire.” I sympathize with Lehrer’s will to distill the content of these mysterious paintings, but I don’t see the exultation in them. Far from any sense of ascension, their pull is downward, toward the chthonic. These paintings are dark in every sense, and seem like diagrams of some dangerous vortex or narrowing tunnel to what might be a place of entrapment.

The last works in the show, chronologically, are a couple of quilts made in 1989. Their forms are very different from the more conventional ones that Ramberg had made during her hiatus from painting a few years earlier. In them, sequences of narrow, symmetrical vertical columns are built up out of horizontal stripes against a background with a much more subdued stripe pattern. Here, at last, there’s a more substantial connection, not so much with her recent paintings as with those she’d been making 15 years before—those columnar “sleeves” and “ticklers.” But even in these quilts, she’s still skirting the psychological content that imbues all her paintings. Were the formerly parallel tracks finally beginning to converge? Sadly, we’ll never know. Shortly after making those last quilts, Ramberg was diagnosed with a form of early-onset dementia and stopped making art. She died in 1995, at the age of 49. By that time, she’d already become indispensable to Chicago’s inside art history. Isolating and recombining body-image fragments, she sought techniques for self-understanding without judgment. That effort made Ramberg essential to a history much broader than that of a single city.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks

The late actor and director leaves behind a roster of classic films—and a much safer and juster California.

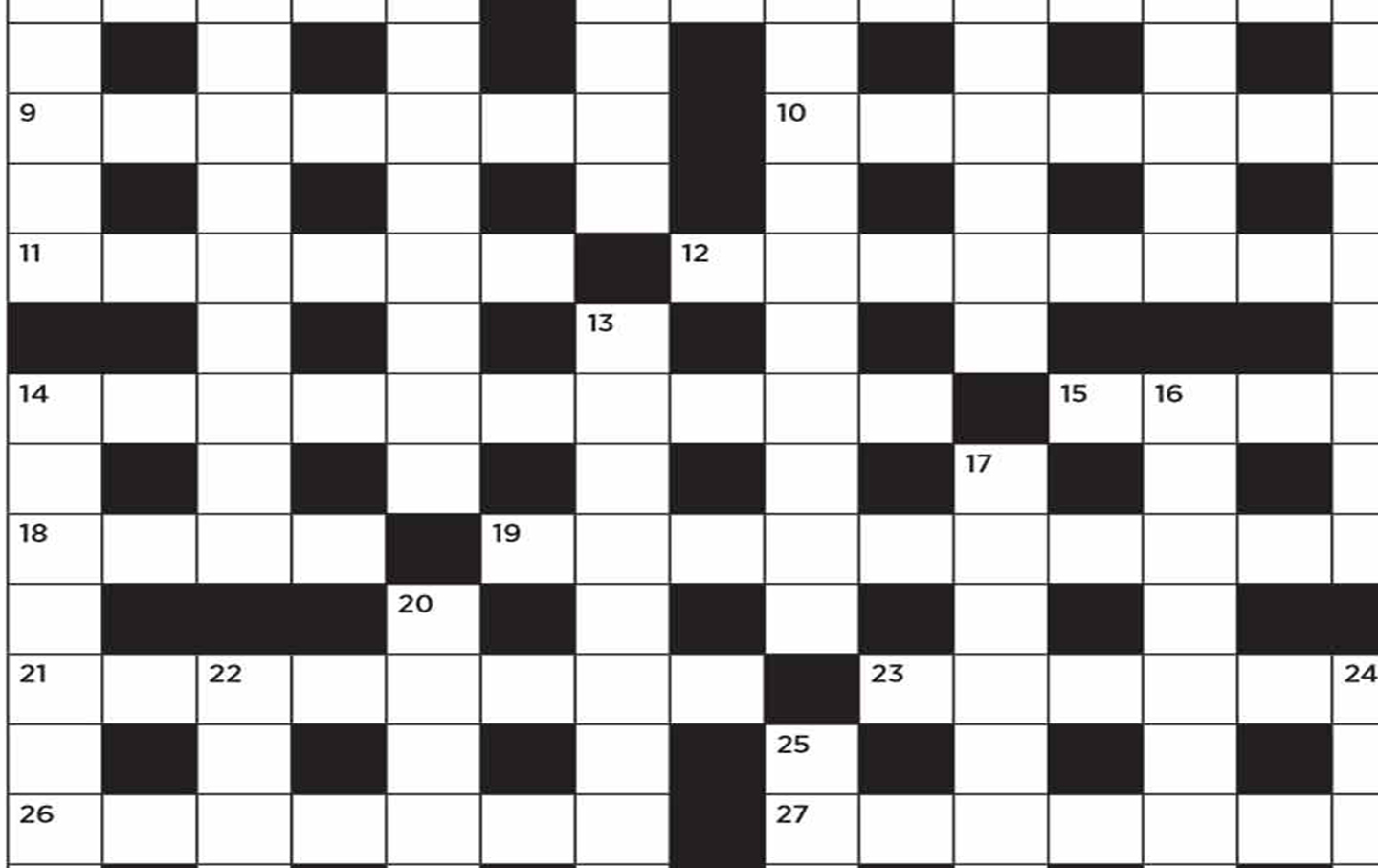

Solution to the “Big Event” Crossword Solution to the “Big Event” Crossword

If questions remain after reading this, please write to sandy @ thenation.com.

Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments

Dev Hynes moves between grief and joy in Essex Honey, his most personal album yet.