The Art of Reading Like a Translator

In The Philosophy of Translation, Damion Searls investigates the essential differences—and similarities—between the task of the translator and of the writer.

By just about any measure, Damion Searls, an American translator of German, Norwegian, French, and Dutch, is one of the leading practitioners of his art. He has translated the works of widely acknowledged masters (Hermann Hesse, Rainer Maria Rilke), writers who ought to be (Ingeborg Bachmann, Dubravka Ugrešić), and two recent Nobel laureates (Jon Fosse and Patrick Modiano). He ranges across eras and prose styles—Searls has translated as much contemporary fiction as he has 19th-century philosophy—but what unites his books is the elegance of his translations: Even his version of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s famously dense Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus is stylish. Marjorie Perloff, a Wittgenstein scholar who’s translated the philosopher herself, praised Searls’s Tractatus for capturing the “literariness of the text,” a compliment one could easily give to any of his 60-plus books. Considering Searls’s success in and commitment to translation, it comes as a surprise that he starts his latest book, The Philosophy of Translation, by declaring that translation isn’t all that much different than any other form of writing. “Writing as a translator,” he argues, “is pretty much the same as any other kind of writing.”

Books in review

The Philosophy of Translation

Buy this bookSearls’s point is that all writers, translators included, have the same tools. If I’m trying to produce a novel in English, whether that novel is an original or a translation, then the English language is my medium, just as oil paint was for Claude Monet. It follows, then, that I’m as constrained by English—by its rules, its conventions, the linguistic habits of its speakers—as Monet was by his chosen canvases and brushes. Searls admits that translators deal with the “especially strong constraint” of the tight relationship between the original text and the new one, but the latter is still, well, new. At the end of the day, the translator’s job, the essential aspect of moving a text from one language to another, is to write a new book—and write it well.

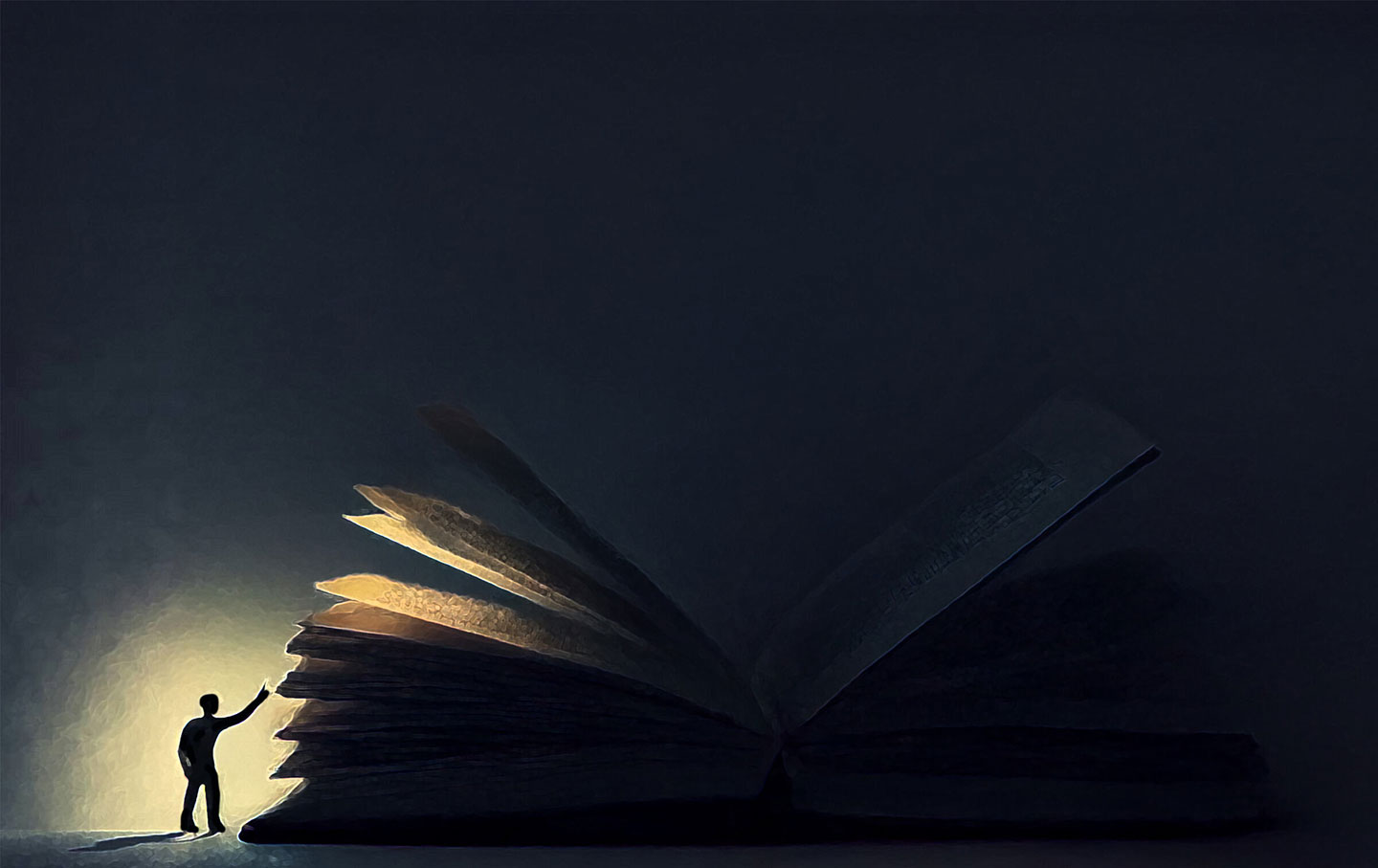

But Searls’s book isn’t called The Philosophy of Writing, and his claim is not that translation isn’t unique, but that the writing aspect of it isn’t. What differentiates translation from the other literary arts, he argues, is the way translators read. The Philosophy of Translation is a meditation on what it means to read like a translator, which means, really, that it’s an ode to close reading. Searls writes in his introduction that, rather than adopting the imperious stance of theory—a discipline that too often “suggest[s] the foolishness or impossibility of trying to engage in the practice” without it—he hopes that practicing translators will “find these ideas suggestive, illuminating, or at least lovely.” As a practicing translator myself, I certainly did, and yet what I most enjoyed about The Philosophy of Translation was something more implicit in its mission. Without claiming that he set out to do so, Searls has written a philosophy of what, how, and why to read.

Searls treats reading as a translator not as an approach to certain books, something to be switched on at the desk and off on the couch, but as a stance toward literature that treats reading as “something like moving through the world.” This stance requires you to read carefully and trust your judgment and interpretations; Searls is blunt about the fact that translators “decide what’s important and what’s less important, then re-create what they’ve decided is important.” Book critics, incidentally, do the same—a reviewer who can’t pick and choose just writes summaries—and, like a good critic, translators must maintain a sense of humility. “I feel that I read deeply and well,” Searls writes, “but not that my reading outranks or preempts other readings.” Relatedly, he accepts that his taste is shaped by the provinciality that a translator cannot help but notice. Reading and interacting with literature from around the world is an exceptional reminder that “any genuine claim to universality [is]…laughable.” It’s simply not possible for anyone to know more than a fraction of the languages, literatures, and schools of thought that are out there. Reading as a translator means remembering that, and seeing it not as a failure or an impoverishment but as a part of life.

Acknowledging that unfamiliarity is natural means understanding that something new doesn’t have to be alien or strange. An “underappreciated aspect of the translator’s experience,” Searls argues, “is that, subjectively speaking, nothing we read is foreign.” Initially, he presents this thought as an elementary fact. When he sits down to read a Fosse novel in Norwegian, it can’t be foreign to him: There it is, a physical book in his hands, its sentences going into his brain—what could be foreign about that? Really, though, he’s making a philosophical point, one that he fleshes out by briefly visiting millennia of translation history. In antiquity, he writes, translators were expected simply to convey knowledge. Nobody expected books to be translated word for word or even line for line; praising the “literariness” of a translation would have been unheard of. This started to change in the Renaissance, when translators were expected to bring both “content and form, body and soul” into the new language—a vision that made translation into a literary art, not an intellectual utility. Starting with the rise of German Romanticism in the late 18th century, translation also became a form of nation-building. Writers and philosophers—especially Friedrich Schleiermacher, whose writing on translation Searls discusses at length—attached an identitarian value to their work, arguing that a country’s books, both translated and not, built its soul. Somewhat contradictorily, though, the German Romantics also believed that language is “intimately coterminous with the [writer’s] mind and body”—i.e., that if I wrote in a language other than English, I’d not only write different words from these, I’d use them to express different emotions and thoughts. This is a tough idea for a translator to contend with, and Searls doesn’t buy it. While not dismissing out of hand the capacity that language has to shape cognition, he feels, fundamentally, that we aren’t as different from each other as the German Romantic vision of language would suggest, and we certainly shouldn’t read or translate as if we were. Searls’s theory is that reading as a translator means rejecting the idea of foreignness wherever and however we can. This is a major realignment of how we see translation and its practitioners.

Perhaps the most frequently used image of translation is that of a person crossing a bridge. In this visual metaphor, the translator journeys alone from Language A to Language B, gets a book, and brings it back into Language A. The problem with this idea, as Searls writes more than once, is that “once you posit a gap, you can’t bridge it.” If we see translators as a go-between connecting literatures, or cultures, that don’t touch, then we approach translations with a feeling of difference that, in the worst case, can resemble a linguistic variation on stranger danger. Searls proposes another approach: “Rather than beginning from an assumption of two separated contexts, we should view the translator as someone in a diverse community who reads a text in one language and produces a text in a different language.” No bridge, no gap, no journey—nobody’s a stranger here.

So what does a translator do in order to produce a new text in a different language? Searls uses a variety of examples from both his work and other translators’ to illuminate the process. He discusses rhythm and register, two elements of a source text that are often impossible to reproduce, as well as the eternal difficulty of imparting background knowledge to readers who may have little to none. (Does he assume, when translating German, that his American audience will understand that “Kaiserstrasse” means “Kaiser Street?” Not necessarily!) In a chapter on synonym use—it’s a convention, in English, to rely heavily on synonyms rather than using the same word twice in one passage—he compares Emily Wilson’s lavishly varied retranslation of the Odyssey to Marian Schwartz’s aggressively repetitive retranslation of Anna Karenina to demonstrate a point that becomes central: For Searls, translators “don’t translate words of a language, they translate uses of a language.” By the latter, he means a mix of emotion, context, and connotation that seems—and is—highly complicated, and yet becomes intuitive in the practice of translation. Repeating words is a use; so is varying them. When we do the latter, of course, we continue to change our use of language. The word madre always means mother, for instance, but I use it one way to describe the mother superior of a convent, a second way to talk about my mother-in-law, and a third to tell you a story about my own mom.

Searls roots this argument in the French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s The Phenomenology of Perception, comparing the way a translator moves through a text to the way any person moves through the world. If I see a chair—as per Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology—I know I can sit in it. If I see the word madre—as per Searls—I know I can translate it as mother. What matters is that we use those two words the same way, just as we use a chair the same way in Spain and the United States. I’m currently translating the Spanish writer Clara Usón’s novel The Shy Assassin, which contains a long, wrenching passage about a narrator’s troubled relationship with her unhappy, alcoholic mother, a woman who silently resents that the Francoist Spanish society in which she came of age gave her no option but to be a housewife. I know I can translate this section using words and phrases that evoke the same emotions I felt and the same images I imagined while reading that passage for the first time. Or I could turn it into a passage about how close the narrator is to her dad, just as I could set the chair on fire—but then I wouldn’t be translating, just as I wouldn’t be sitting in the chair.

Key to this vision of translation is that it doesn’t especially care that I, the translator, did not also come of age in Francoist Spain. My difference from the character I’m translating isn’t relevant; nor are the ways in which the narrator and I might be strangers to each other. What is important is the closeness to her that the original text makes me feel. Again, this is Searls rejecting foreignness: He’s not suggesting that I, the translator, should be unaware of or uninformed about the differences (and similarities) between Spain in the 1970s and the United States in the 2020s, but that translation isn’t fundamentally an expression of those differences—or of difference, full stop. It is, rather, a way for me to move my emotional response to the Spanish text into an English text to which, I hope, Anglophone readers might have that same response.

Of course, the Anglophone readers in question have to be open, which Americans have not traditionally been. Until recently, publishers in the United States habitually omitted translators’ names from book covers so readers wouldn’t register that they had picked up a translation. This practice perpetuated a vision of translation as an invisible art at best or, at worst, a strange practice that should be covered up rather than acknowledged. This, in turn, reinforces Searls’s point: that translation need not be a disembodied and alien habit. The Philosophy of Language offers us another vision of translation for translators, but the reason that it also works for readers—is, indeed, necessary for readers—is that it’s the audience, not the translator, who ultimately decides whether or not to take a book as foreign. Another way to put this is to say you don’t have to be a translator to read Searls’s way; you don’t have to read more than one language to see your reading self as a member of a huge, heterogenous, swirling community in which books and readers from around the world collide and converse.

If this is how you think of reading, then its importance becomes plain. It is also plain that what you read should be good. It’s a cliché by now to say that literature builds empathy; it also isn’t necessarily true. We are, after all, in both an era of declining empathy, at least in political discourse, and an era of bad books. Writers who churn out simple, emotionally manipulative novels get sizable deals and acclaim, while too many of those who labor over intellectually challenging fiction have to struggle to reach minute readerships. Amazon is at fault for some of this; so is the corporate consolidation of the publishing industry. But we don’t have to read only what’s easy, just as we don’t have to read only what’s American. In Searls’s brief discussion of AI, which he does not see as a meaningful threat to writers, he insists that a machine cannot engage in “the deeply human act of reading: the process, subjective and objective at once, of engaging as an individual person with something that exists out there in shared reality.” A good book, and only a good book, has the effect of reminding us not only that reality is shared, but also that others don’t see it or feel it as we do. For Searls, the way to tell bad writing from good is this: “Bad writing is predictable, good writing is defamiliarizing.” Put differently, a good book either feels unfamiliar or makes us feel less familiar to ourselves. In reading it, we can remember that this unsettling sensation—this sensation of foreignness—is, in fact, not foreign at all. It’s human; it’s an expansion of the mind and the heart. A good piece of writing, if and only if it’s read well, can do that to us. In The Philosophy of Translation, Searls shows that reading as a translator, or reading like a translator, is a method of reading very, very well.