How the Western Literary Canon Made the World Worse

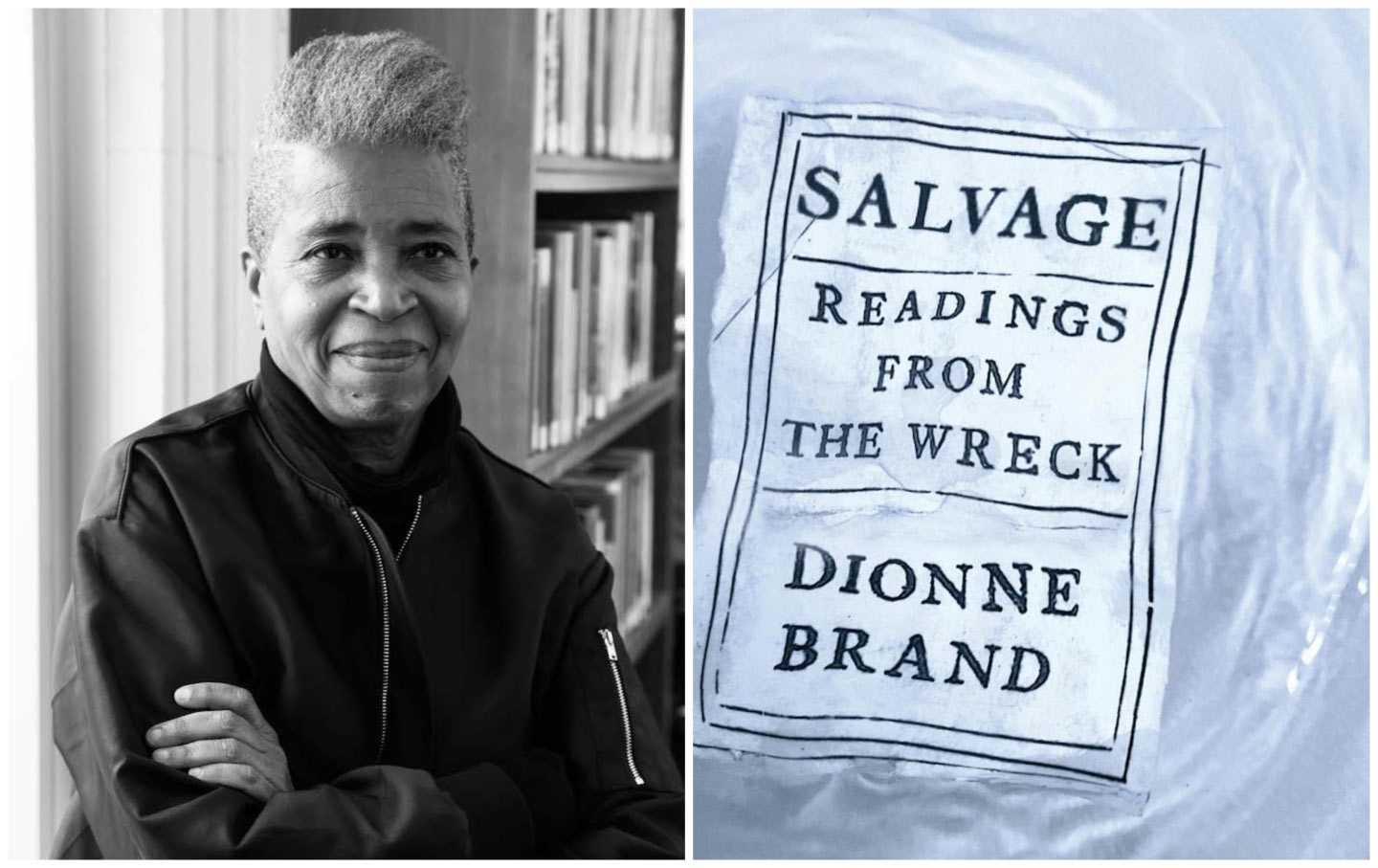

A talk with Dionne Brand about her recent book, Salvage, which looks at how the classic texts of Anglo-American fiction helped abet the crimes of capitalism, colonialism, and more.

For decades, the poet, novelist, and essayist Dionne Brand has shaped the way that Black life is discussed. Her new book, Salvage, revisits canonical texts of English literature to foreground the ways in which they licensed capitalism, colonization, slavery, and more. In discussions of Robinson Crusoe, Jane Eyre, and Vanity Fair, among other works, the former poet laureate of Toronto attests to the lasting impact of the classics in shaping the modern world. She also points to an alternative mode of reading those texts to resist their legitimations of modern ills and to an alternative tradition of writing that might still offer a route out of present modes of oppression.

The Nation spoke with Brand about capitalism’s aesthetics, the novel’s relationship to colonization, and a literary tradition alternative to the classic English novel.

—Elias Rodriques

Elias Rodriques: What led you to write this book about English literary classics now?

Dionne Brand: My writing life, and the persistence and flooding of 17th-, 18th-, and 19th-century English literary texts on all formal instruction, on narrative structure itself, and on structures of feeling as well. Many critics have written and analyzed this phenomenon, notably Simon Gikandi in Slavery and the Culture of Taste, Edward Said in Culture and Imperialism, and Lisa Lowe in Intimacies of Four Continents, and many, many anti-colonial writers speak of the influence of these texts. We are all immersed in it, willfully and involuntarily. As I say in Salvage, narrative structure seems to still be located in its sediment. And it’s more than sediment, but processes of understanding—understandings of the world—are in its meter.

So the question for a writer like me is always, “What am I writing into? What am I writing over?” Every aspect of writing and of narrative fiction is concerned with it. How does fiction-writing sit in, take for granted, and continue along the trajectory of the structure of these texts? What is being imported, what lies dormant, when these models are employed? I observe a certain decay in the elements or instruments of point of view, arc of story, landscape, and the like. So what led me was a process of undoing not merely subject but process.

ER: You write at various points that these classics of English literature are part of and produce “the aesthetics of capitalism.” What are those aesthetics, and what do they do?

DB: These texts came out of and were immersed in the period of transatlantic slavery and colonization. They and their protagonists had a symmetry with capital and were/are seriously didactic. Capitalism is/was not merely an economic, qua economic, process, but also organizes the affective and haptic. These cultural products evangelized in this way the good life, the lovely life—what is lovely, beautiful, and desirable—and the position from which to observe what is beautiful and desirable was/is the bourgeois position. Recall how many times in these texts the amount the protagonist makes per year is recounted (not to make a pun) or their debts or profligacy reported. Accounting—or adding up—the fiduciary position of such beauty and desire was intrinsic to these novels. There’s nothing wrong with reading those texts. But for me, the question is, “What am I reading?” What happens when a professor, say, or a critic tells you one of these books is beautiful and points out the paragraphs that are so lovely? When one is told to be moved by these texts?

Capital, of course, looks different in any particular period of time. We live in a period where acquisition, obtaining lots of money, is seen as beautiful, and moneyed people are said to “live beautifully.” Moneyed objects signify a lovely life, a lusty life, a pleasurable life. In our time, a Gucci bag and those kinds of products signify the beauteous, the pleasurable, and therefore the desirable. If I can have them, I feel superior because within the equation, they are have-able, desirable, but not everyone can have them. The piquant enjoyment of them is also that not everyone can have them. If I have them, I’m better than those who don’t have them. That’s the rubric of capitalism and its aesthetic. My point is to trace how this enters the novel as common sense.

ER: So why does so much of your book focus on the novel as opposed to, say, drama?

DB: Importantly, the novel circulated more than drama. It was a kind of new technology moving swiftly and effectively through all the colonial educational systems.

The novel comes out of that period of the massive accumulation of wealth by Europe through the oppression and immiseration of most of the rest of the world. The stories that have to be told about the conquest, about the new shape of the world, about Blackness, about Indigeneity, about the emerging middle classes, and about the bourgeoisie’s support of the project of accumulation and, notably, of haltering the aristocracy—the novel participates in that moment and uses all the apparatus and forms of capital. It makes new language as capital makes new machines. It makes a narrative form to accompany this emergence of the bourgeoisie of that period and of its way of living and its continuation. One doesn’t only need armies; one needs the educative: instruction in social location underpinned by a spiritual imperative

ER: And those novels live on.

DB: The effects of texts that were part of that colonial project are still heavily felt and recycled in this moment. That moment is not even over, even if it’s 400, 300, 200 years since those texts were made. They’re now so embedded in contemporary works that they are unseen. Because they are significant for a certain practice of governing, they become commonsensical, their literary structure becomes commonsensical, and their interpretations become commonsensical. Their period isn’t simply their period; they hover over the lives we live. And the situation that we live in emanates from that which is told in those texts, and from the practices that produced those texts. Those texts keep being reworked because the system that produced them is an evolving system that doesn’t leave them behind but wraps them into the processes of now.

Now, not all narrative fiction just reproduces capitalism. It is not that one never breaks through those boundaries. It is not a monolithic structure that imposes monolithic thinking. But it bears investigation each time I address the page: “How do I reproduce the world without reproducing capital?” Capitalistic economic structures and social structures have so infected our daily life that we no longer see ourselves outside of that regime. What of my days can I recover outside of that? And as a writer, what of those days may I write down? I am chained to that economy because I live in its orbit. But still, how do I write differently and break up what Fredric Jameson calls the “monopoly of interpretation” and, therefore, the monopoly of power? How do I recover that which is outside (which, granted, has become meager) of that form, that administrative structure of capitalist economy, that takes over what I call my life? And what is my life now?

ER: Though much of this book is about reading, it sounds like you are saying it is partially about how one writes.

DB: Yes! What’s in a sentence? How do I begin this sentence? And what am I transporting? Even in the velocity of the sentence or in the subject, what am I transporting? I had a friend who once said to me that he would read the first sentence of a novel and learn who the novel was directed toward. He meant—in terms of class, race, and gender—who the novel considered its interlocutor; who it valorized and supported. It’s also worth asking: Who created the “rule” that, in a novel, the main character goes through a process of transformation? It’s deadly. It’s a deadly, deadly project.

ER: I’ll relay that message to my editor.

DB: I’m not saying all novels do this. But that’s the dominant view of what a novel must do in this Euro-American moment of novel-writing: the process of transformation. That rule is repeated in every self-help book, TV program, whatever. If capitalism’s so great, why do we need all this self-help stuff? I suppose it is to make synergies with capital accumulation. The proliferation of that narrative of transformation: From what to what? I’m joking, but it bears thinking about.

ER: Much of what you have said is in line with some Marxist histories of the novel. Perhaps this is too arcane, but I’m curious about your relationship to Marx and Marxism.

DB: My relationship? [Laughter] I’ve learned quite a bit about it. I like to remember a joke that Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o made when he visited Toronto. I was chairing a panel with him and a couple of other writers. Someone in the audience got up and asked him, “Are you Marxist or something?” He said, “Marx didn’t invent the working class, you know. He just described it.” [Laughter] That’s my position. Marx’s work has had a great effect on me and is fruitful for describing the world that I live in and the history that I come out of. It isn’t sufficient, but then again, I’m not looking for a Judeo-Christian Bible—I’m not in the least bit religious. I’m looking for things that help me describe the world. Marx does so incredibly. So does C.L.R. James and Eric Williams and George Padmore, Claudia Jones and Angela Davis and so, so many more. So, too, do movements that have come out of anti-colonialism and anti-imperialism. One merely has to observe, to think through what one’s politics might be. If that makes me “in line,” well, so be it—but I would ask who and what is not “in line” with something, and I would refuse to cede some assumed greater amorphous remaining space to a kind of laissez-faire nonideological.

ER: You’re not looking for something to explain everything, and you’re also trying to explain more.

DB: We live in time and in process. I don’t use Capital as a template for everything now. It described a period, and it’s a kind of political/sociological/economic study of Britain at a certain point. For me, Marxism is a method, not a prescription. I must take into account how we live now, what social arrangements exist now, and how and if I might use that method to think them through. The question of transatlantic slavery is minor in that work. It’s mentioned, but not at length. And that’s interesting. But the method of analysis about capitalism and capitalist production is legit. And so much has happened since.

ER: In Salvage, you also allude to an alternative to the classic tradition of the English novel. What do these alternative traditions offer?

DB: The letters of Ignatius Sancho and the book by Ottobah Cugoano are being written at the same time that these novels are being written. Their abolitionist thinking—their ethical stance that slavery is abhorrent—is going on while this other view of the world and its economics are being written and underwritten in narrative fiction. Their thinking loses the battle. That’s all. The structure of capital and its production of literary works, artworks, and so on overwhelmed the other idea, the other humanism. They’ve simply won by force.

These works—of Sancho, Cugoano, Mary Prince, Harriet Jacobs—are often read merely as an appeal to the dominant idea, but they are in fact a rebuke of the dominant idea. They are a rebuke to the dominant structure, the dominant socioeconomic, political, and aesthetic structure. Under the weight of that power, these works are read as if they wish to be a part of it.