Edward in Palestine

Reflections on Edward Said 20 years after his death.

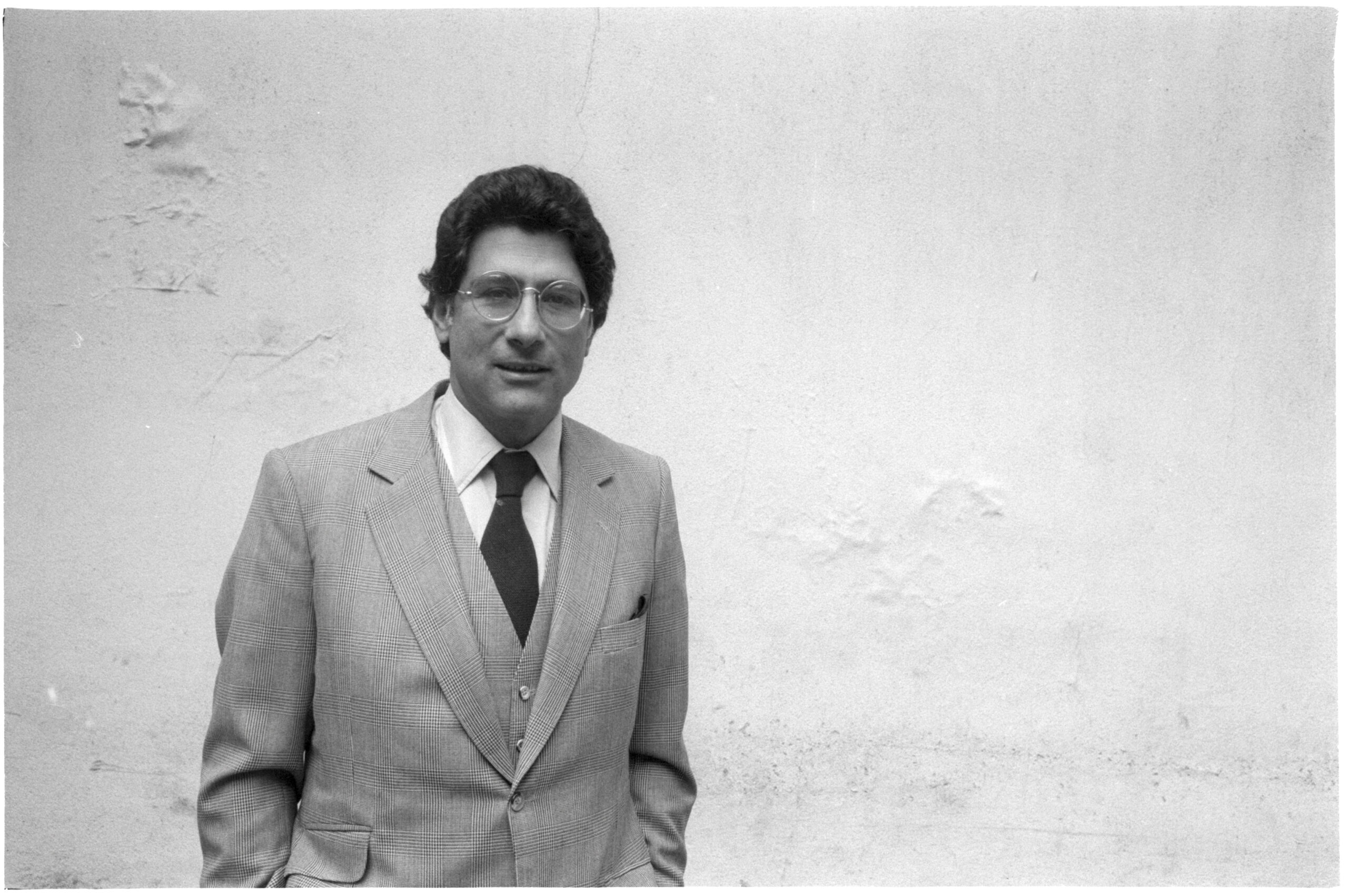

Edward Said

(Sophie Bassouls / Getty)“Hard to believe,” we kept saying to ourselves as we lived through another troubled (and deadly) year in occupied Palestine: It was hard to believe that it will be 20 years this September since Edward Said died. Like so many of his friends, we could still hear his voice, sometimes angry and hectoring, sometimes humorous—and, so very often, thoughtful, insightful, and surprising. Both of us had met Edward in New York on a number of occasions but it was his visits to Palestine—even after his diagnosis with leukemia in 1991—that we most treasured.

Before there were these visits there was a failed visit. “Edward Said bahki min New York,” the voice said:“Edward Said speaking from New York.” It was a March day in 1988, and there were a few smiles in the crowded room at the Ambassador Hotel in Jerusalem over Edward’s colloquial Arabic. There was also a sigh of relief from the organizers of Birzeit University’s “Twenty Years of Occupation” conference that, despite a few crackles, Edward’s voice was coming over clearly on the speaker.

We at Birzeit University and elsewhere in the occupied Palestinian territories were used to technical glitches. We were in the midst of the first Palestinian intifada back then and were unable to hold the conference in the university, which was closed by military order on January 10, 1988 (it would not be reopened until April 30, 1992). During those years of mass civil resistance in the occupied Palestinian territories, universities were not the only things closed by military order—at times, even elementary schools were deemed a threat to security.

Organizing an international academic conference and inviting the participants to Jerusalem was one of the ways the university resisted the closures and continued its academic activities—but it was not easy. In the West Bank, with the exception of annexed eastern Jerusalem, the Israeli army had cut off all international calls. A few weeks earlier, Penny had traveled from Ramallah to the post office in western Jerusalem to call Edward, hoping to persuade him to come to the university’s conference. “You’re trying to get me arrested,” Edward replied to the invitation. At the time, Penny wondered if he was being overly cautious; only later we would learn that an edict had been issued by the Israeli government under Yitzhak Shamir declaring that Edward was banned from entering, presumably because he was a member of the Palestine National Council. (He resigned from the council in 1991 to protest Yasir Arafat’s support of Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait.)

It was not until June 1992, just after Birzeit University reopened, that we would welcome Edward in person. Although he had been born in Jerusalem and had his first schooldays there at St. George’s School, he had not been back to the city since Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza in 1967. It was, for him and for us, a signal occasion.

Like the failed visit, things did not go altogether smoothly. Edward’s first scheduled seminar, to be held shortly after the campus reopened, was canceled when the students called a strike over an Israeli military action that had been launched for reasons we can no longer remember. It was Penny’s job, along with colleagues in the university’s public relations department, to hastily assemble a conversation with Edward some days later. A former Birzeit student from the Jalazoun Refugee Camp brought Edward from the elegant American Colony Hotel in Jerusalem to Birzeit in his battered car. There, cultural studies professor George Giacaman and political scientist Ali Jarbawi introduced Edward to a large student audience and everyone got to see a lively exchange. Edward “categorically” defended the embattled Salman Rushdie and criticized political Islam “somewhat impetuously,” as he would later ruefully note in an article on the trip written for Harper’s. Afterward, several students from the Islamic Bloc noted “their points of disagreement” but welcomed Edward and told him they hoped he would return.

During this visit, Edward received Birzeit’s first honorary doctorate. But as he later recalled, he was not there for the honors but in a search for connection, even as he acknowledged that he found exile “liberating.” Edward’s cosmopolitanism, his sense of disconnection, was, as he wrote in Reflections on Exile and Other Essays, important: “Exile is strangely compelling to think about but terrible to experience. It is the unhealable rift forced between a human being and a native place, between the self and its true home: its essential sadness can never be surmounted.”

Whether searching for his family home in the western Jerusalem neighborhood of Talbieh and discovering that it now hosted the evangelical International Christian Embassy, or marveling at the amount of barbed wire strung throughout the countryside, Edward always was honest about what he was seeing and thinking. His rapt attention in meetings and while listening to Palestinians he met was often balanced by an acerbic wit. Edward never shied away from making his own views clear: He often expressed his dislike of Jerusalem as being too burdened by religion and provincialism. We particularly enjoyed his description of a visit that he and his family made to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem’s Old City, which was “exactly as I recalled it—a rundown place full of frumpy, middle-aged tourists milling about in the decrepit and ill-lit area where Coptic, Greek Orthodox and other Christian churches nurtured their unattractive ecclesiastical gardens in sometimes open combat with one another.”

A romantic, Edward was not. A secular humanist, he definitely was.

Edward’s “first thought on leaving the West Bank” struck us as both apt and original, about

how small a role pleasure now seems to play not only in Israel but in the Occupied Territories. A harsh, driven quality rules life, by necessity for Palestinians, by some other logic, which I can barely understand, for Israelis. After so many years of thinking about it, I now feel that the two people are locked together without much real sympathy, but locked together they are.

Over our many years in the Occupied Territories, we have often thought of this reflection and felt it to be so true. It reveals Edward’s ability to look from a distance yet sympathetically, not paternalistically or as an elitist but with concern.

As much as Edward seemed to want to be understood by the Palestinian community, he never seriously considered relocating to live and teach in the West Bank. At times, his harsh criticism of the Palestinian intellectuals he met on his visits did not fully take into account the conditions under which they had to live and work. On the other hand, Edward was tireless in offering his voice and in using his privileged vantage point to challenge the injustice and to advocate what he believed needed to be done.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →This was also true of his unrelenting criticism of Arafat’s rule and the failures of the Palestinian Authority, which took control over the occupied territories after 1995 and the signing of the Oslo Accords.

Edward’s first visit ushered in an almost dizzying series of returns to Palestine during the 1990s—three in 1998 alone. It was as though, in opposition to the earlier Israeli attempts at keeping him away, he was determined to keep coming back.

It was during one of these visits that Raja met Edward at the American Colony Hotel and tried to warn him about how merciless Israel can be against those who speak out, against those whom it deems to be its enemies. Edward’s heartbreaking response was: “What can they do to hurt me, I’m already half-dead.”

Raja then told Edward about his new writing project—a memoir of his family—and in particular his difficulties in writing about his relationship with his father, Aziz, who had been murdered in 1985. Ever the dedicated teacher, Edward responded with a remarkable and enormously helpful list of reading material for Raja. He then said in sympathy, “I figured out my mother, but my father remains a mystery to me.”

On another occasion, Edward and his son Wadie, who was volunteering at a labor rights NGO in Ramallah, came over to our house. A melancholic conversation followed concerning the Oslo Accords and how the PLO had in effect signed a surrender document. But, not wishing to let things end on a sour or bitter note, Wadie and Edward leavened the evening with jokes from Wadie and gossip from Edward on mutual friends and enemies. Ahdaf Soueif, an accomplished novelist and founder of the Palestine Festival of Literature, once described herself as “one of Edward’s 3,000 close friends.” That evening, we got what she meant.

There was also the time Raja, Edward, and Ibrahim Abu Lughod—one of Edward’s oldest and dearest friends—went to Nablus together, where they participated in a policy discussion at one of Palestine’s ubiquitous NGOs. As Edward launched into his presentation in Arabic, he glanced at Raja. “Am I causing you pain?” he asked. When Raja nodded, Edward switched to his elegant English.

On one of Edward’s visits in 1997, we very much enjoyed going with him and the writer and classical singer Tania Nasser to a concert in Jerusalem by the pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim. Barenboim dedicated his encore to Tania (albeit not by name) and the Palestinian hospitality she had shown in inviting him to dinner. Two years later, Edward would bring Barenboim to Birzeit University for a remarkable concert. The ensuing years would see the flowering of their mutual project, which remained so important to Edward: The East-West Divan Orchestra.

Edward’s three visits in 1998 were particularly significant for him. He was deeply affected by his meetings with young people and angry about the failing Palestinian leadership. He also had a message of his own to deliver. In the fall of 1998, Edward gave the keynote address at Birzeit’s conference “Landscape Perspectives on Palestine.” It was a complex presentation on the intertwining of history, geography, and memory. Edward incisively analyzed this interplay in colonial conquests and 20th-century nationalisms, in particular the Zionist movement’s rewriting of the history of Palestine into an exclusive national narrative and he noted as well the “collective Palestinian inability” to do so.

Edward’s analysis, however, did not stop there. His conclusion—which he would elaborate over the all-too-brief years remaining to him—challenged the political thinking on both sides of the Palestinian-Israeli divide. Noting that the “problem with the American-sponsored Oslo process was that it was premised on a notion of partition and separation,” Edward affirmed that, if anything, what was needed was more connection, more integration:

Israelis and Palestinians are now so intertwined through history, geography and political actuality that it seems to me absolute folly to try to plan the future of one without the other.

Edward argued in that keynote—as he would continue to do to the end of his life—that the two communities must “confront each other’s experiences in the light of the other.” Israeli Jews, the stronger party, must confront “the dispossession of an entire people” while Palestinians, the weaker party, must still “face the fact that Israeli Jews see themselves as survivors of the Holocaust, even though the tragedy cannot be allowed to justify Palestinian dispossession.” In his introduction to Reflections on Exile and Other Essays, Edward explained “that only by seriously trying to take account of one’s own history—whether Israeli or Palestinian—as well as that of the other can one really plan to live with the other.”

Edward accompanied his belief in a common future with action, too. After the Birzeit conference, he left for Nazareth on his first (and only) official invitation from an Israeli institution, the Israeli Anthropological Association—the “best-attended event in the organization’s history,” according to the organizer Danny Rabinowitz. Edward returned the next evening to our house for a meal featuring cooked Swiss chard from our garden. “The food was terrible there,” he commented at one point, leaving us with this as his sole observation on his only official presentation before an Israeli audience. Even Edward was not always profound.

Over the next several years—whether in the amazing number of articles he penned for the Arabic press challenging what he called “the shabby state of discourse and analysis in the Arab world,” or in his tireless work with Barenboim to foster the development of the East-West Divan Orchestra—Edward was profoundly on a mission.

At the time of his death and after, commentators said that Edward sometimes advocated a binational state and sometimes a one-state solution—variations on a theme, perhaps, but distinct in their approach to national rights and self-determination. Edward himself, in an extended three-and-a-half-hour interview with Charles Glass shortly before his death, was clear: “When anyone asks me what is the solution, I say I distrust that.” What Edward was offering us—and continues to offer today, in an ever-worsening time—was not a policy option a project for thinking through and working toward a common future. For him, connection—not partition—was the only way forward. As we witness in the West Bank today the distressing effects of extreme nationalism and the absence of a healthy separation between religion and politics, Edward’s vision of a common future is sorely missed.

Edward’s final visit to Palestine was in May 2001, during the violent time of the second intifada. He came to mourn and attend the funeral of the influential political scientist Ibrahim Abu Lughod and his burial in the family plot in Ibrahim’s beloved Jaffa. It was the last time we would meet. Edward was not buried in Palestine; his ashes rest in the Lebanese mountain village of Deir al Shweir, where his family often spent summers. He has left all of us in Palestine, however, with not only the memories of his visits, conversations, and writings but also an imperative to consider for ourselves how a common life in our country might be realized.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Best Albums of 2025 The Best Albums of 2025

From Mavis Staples to the Kronos Quartet—these are our music critic’s favorite works from this year.

Forrest Gander’s Desert Phenomenology Forrest Gander’s Desert Phenomenology

His poems bridge the gap between nature’s wild expanse and the private space of one’s imagination.

Capitalism’s Toxic Nature Capitalism’s Toxic Nature

A conversation with Alyssa Battistoni about the essential and contradictory nature of capitalism to the environment and her new book Free Gifts: Capitalism and the Politics of Nat...

Solvej Balle and the Tyranny of Time Solvej Balle and the Tyranny of Time

The Danish novelist’s septology, On the Calculation of Volume, asks what fiction can explore when you remove one of its key characteristics—the idea of time itself.

Muriel Spark’s Magnetic Pull Muriel Spark’s Magnetic Pull

What made the Scottish novelist’s antic novels so appealing?

Luigi Pirandello’s Broken Men Luigi Pirandello’s Broken Men

The Nobel Prize-winning writer was once seen as Italy’s great man of letters. Why was he forgotten?