Down in the Dirt With Elfriede Jelinek

A long awaited English translation of her shocking magnum opus, The Children of the Dead, asks its readers to look at the violent history buried just beneath their feet.

Elfriede Jelinek, 1986.

(Photo by Schiffer-Fuchs / ullstein bild via Getty Images)

If you think too hard about it, reading any book in translation can get frustrating. Yes, gifted translators can not only capture some of the original author’s stylistic peccadilloes and thematic preoccupations, while inventing their own style along the way. Still, a successful translation can sometimes resemble a Xerox: The poetry of the prose, to paraphrase Robert Frost, is lost in translation.

Books in review

The Children of the Dead

Buy this bookThis loss is felt especially deeply when reading Elfriede Jelinek, the Nobel Prize–winning Austrian novelist, poet, playwright, translator, and critic. This is attributable both to the generalized inflexibility of the German idiom and Jelinek’s more private tendency to write in a highly idiomatic dialect of Austrian-German which, the author has joked, proves “incomprehensible even in Germany.” Indeed, it has taken nearly three decades for Jelinek’s ostensible magnum opus to be rendered legible for English readers. And reading the new translation of The Children of the Dead (first published in 1995 as Die Kinder der Toten), one quickly senses what took so long.

Jelenik is probably best known in the English-speaking world for 1983’s The Piano Teacher. A loosely autobiographical S&M psychodrama about a repressed, middle-aged piano teacher who yearns to be dominated by a jockish pupil, it was the first of Jelinek’s books to receive an English translation. Its renown also benefited from a very good 2001 film adaptation, directed by Jelinek’s countryman Michael Haneke and starring Isabelle Huppert. Other English translations of her novels have circulated, largely put out by small, independent presses, but few have had mainstream success. Her voluminous body of plays and poems are, by comparison, practically impossible to track down in translation. Part of this has to do with Jelinek’s status as a relatively minor literary figure outside of Austria (and even there, she seems to be regarded as a bit of a crank, pounding out blogs and op-eds railing against Austrian culture, politics, and the fascist past the nation would sooner forget). But it likely has more to do with the toil of translating her.

Jelinek’s prose is dense, chock-full of localisms and bits of political history, and riven with that most Germanic form of humor, die Wortspiele—puns, basically. Her early novels were marked by a crisp, staccato, slightly playful quality. Take the opening lines of 1989’s Lust: “Curtains veil the woman in her house from the rest. Who also have their homes. Their holes.”

By the time of 2000’s Greed, that crispiness had softened somewhat, her linguistic playfulness descending into anarchy: page-long paragraphs, sentences that seem to go on forever, riffs nestled within riffs. One critic called Greed “unrewarding,” another “atrocious.” Others were slightly more charitable, laying the blame on a rushed-to-market translation. “It would have been better to have left the novel untranslated,” wrote Nicholas Spice, reviewing the novel in the London Review of Books. “It’s hard to imagine that Jelinek’s reputation in the English-speaking world will ever recover.”

The Children of the Dead’s arrival is thus auspicious, as a chance to savor a more diligent translation of Jelinek’s prose. But, like Greed, it will do little in the end to disabuse a reader prejudiced against Jelinek’s stylistic excesses: The Children of the Dead is as digressive as it is depressing. As to the translation, one can only marvel. Jelinek’s strange rhythms and word games arrive intact: “Life is not a bowl of cherries, it’s the pits, thus one must either get crushed to death or help things along a bit”; or rhyming “mangler” and “Mengele”—stuff like that.

However culturally specific (or just inane), such wordplay gives life to a serious story. The Children of the Dead is a tale of death, disgust, and despair. But it’s no bummer; it is playful and proudly strange. And it offers a forceful riposte to a culture—one both historical and contemporary—that abjures the buried and the bygone. Its raw pessimism invigorates, even when it risks feeling totally exhausting.

Jelinek is a translator in her own right, and her approach to the task provides some hints at what it is about her work that bedevils those who take it on. In her 1981 translation of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, Jelinek imposed her own deeply felt Weltschmerz on Pynchon’s already plenty pessimistic novel. The German title, Die Enden der Parabel, plays on both the arc or parabola of a V-2 rocket, from which Pynchon’s book takes its name, while also playing on the double meaning of Parabel (there’s that Wortspiele stuff again) to mean, roughly, “The End of the Story.” As the scholar Rebecca Schonsëe suggests, the original novel’s “utopian potential” is, in Jelinek’s hands, frequently “backflipped into a dystopian vision.”

To say that an author is more dystopian, or more despairing of the prospects of human civilization writ large, than the Pynchon of Gravity’s Rainbow gives a rough idea of where Jelinek sits on the long parabola of literary pessimism. Her view of human nature is narrow at best, her wit so caustic that it corrodes.

Jelinek’s examinations of sadism, masochism, domestic assault, and the grander violence of historical memory are frank and unsparing. Her 1980 novel Wonderful, Wonderful Times, a chronicle of a postwar Viennese youth gang that makes A Clockwork Orange seem like Happy Days, concludes with a forensic accounting of a boy murdering his family:

The pistol is now no longer loaded and Rainer puts it aside and fetches the axe from the toilet. It is honed razor-sharp and weighs 1.095kg. The blade is 11.2cm long…. Rainer wields the axe and strikes out without thinking anything at all. Aiming at the head. Rainer’s progenitor instantly caves in beneath the fearful axe blows, bleeding heavily. Bones break, knuckles splinter, tendons tear, veins are severed beyond repair. He keeps on wielding his blows till Father has been totally cut to pieces. Then Rainer picks up his axe and goes over to his mother. A parcel of humanity lying gurgling and frothing in the hall. He strikes at her too…. Nobody says anything or screams. Mother is lying on her stomach, and in that position she is dealt the death blow. She dies.

There is a cold precision to the language (the weight of the murder weapon, measured to hundredths of a gram) that is made even more disorienting in the narrator’s nearly sociopathic distance (Mother is a mere “parcel of humanity”). It is disturbing, and profoundly unpleasant.

In 2004, Jelinek was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. And not without incident: One veteran of the awards committee resigned in protest. He decried the author’s work as “parasitic,” deemed it nothing more than “unenjoyable public pornography.” The official Nobel citation, meanwhile, praised Jelinek’s social critique, as well as “her musical flow of voices and counter-voices.” Yet if her writing is indeed “musical,” it is a kind of dissonant, screeching black metal. Her work afflicts not only the comforts of the bourgeois and presumably Austrian (or at least German-reading) audience, but more general standards of good taste. And it does so with relish. Call her parasitic, or pornographic, and she’ll likely pull a thin smile and nod. Natürlich.

The Children of the Dead is the sort of book that, an English reader might imagine, earned Jelinek her Nobel laurels: a serious, complex work that exemplifies both her stylistic dexterity and her powerful sway as a social and political critic. And it is all of these things. Even if it isn’t her best novel, it is nonetheless superlatively Jelinekian, capturing the author in all her intoxicating, exasperating, whiplashing surfeit. Above all else, the book is a total triumph of the literary abject.

In her 1980 essay The Powers of Horror, the French Bulgarian philosopher Julie Kristeva defined the abject as that which “disturbs identity, system, order.” Her chief examples are refuse and human corpses, which “show me what I permanently thrust aside in order to live. These body fluids, this defilement, this shit are what life withstands, hardly and with difficulty, on the part of death. There, I am at the border of my condition as a living being.” Jelinek was still an obscure writer when the Kristeva essay was published (it is concerned chiefly with Céline, Dostoyevsky, and Artaud), but reading it, one gets the sense that the analyst is diagnosing (or anticipating) Jelinek exactly.

The Children of the Dead abounds with all things abject: waste, garbage, mud, gurgling foams, and especially corpses. The novel’s three main characters are themselves dead. They are, for reasons unexplained, revived, zombie-like, near the perimeter of the Alpenrose, a scenic getaway nestled in the Austrian Alps, in the southern state of Tyrol. The resort draws hikers, holidaymakers, and our trio of the walking dead: Edgar, a professional skier who was killed in an accident; the philosophy student Gudrun, who sliced her wrists open in a bathtub; and Karin, a widowed, middle-aged car crash victim.

Jelinek’s cast is not bound by narrative, at first: The story is propelled by her exhaustive descriptions of the zombies. She describes their decomposing bodies. She describes their hair. She describes, in stomach-churning detail, their sex acts, which seem to multiply exponentially. It is a horny “panorama” of “tender, spoiled, zoonosis-infected flesh.” Even by the standards of Jelinek’s own freewheeling fiction, The Children of the Dead can feel unmoored: equal parts exegesis on consumerism, mother-daughter relationships, Heimat (the German concept of the homeland), and elaborate stage directions for a piece of bizarro black-box theater mounted in hell.

Jelinek’s gnarliness truly impresses. The Children of the Dead reads like a dense catalog of imaginatively offensive images and phrases. It abounds with descriptions of “disco-sticks,” “marmeladish nipples,” “half-stiff decorative flagpoles,” “flabby protuberances,” a “venereal hose,” “suffocankerous mash,” and thickets of folds and slits of flesh, which engulf and reveal themselves in a never-ending, hallucinatory orgy of rotting meat. Any reader who has ever wondered what it might be like to be fellated by a throat rendered “smooth and washed down” by years of decay will have their answer by about page 280. Yet, as with Pynchon—whom she name-checks in the novel—Jelinek’s celebration of puerility has a political valence.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →There is a memorable bit in Gravity’s Rainbow where two members of a postwar resistance group (dubbed “The Counterforce”) infiltrate a dinner party hosted by well-heeled war profiteers, only to find that they’ve actually been lured there and are scheduled to be cooked and prepared as the meal’s main course. In a brilliant bid to escape this cannibalistic supper, the rebel heroes begin ordering an increasingly nauseating array of off-menu dishes, like “pus pudding,” “nosepick noodles,” and “barf bouillon.” Their more refined hosts react with shock and abjection, succumbing to bouts of uncontrollable vomiting, allowing the subversives to slip away. In this scene, as in his larger literary project, Pynchon weaponizes juvenilia as a potent armament wielded against elitism.

Jelinek’s aim feels similar. But it is more than an attempt to outrage the more delicate sensibilities of snoots and snobs. Rather, disgust and abjection offer a negative image for Austria’s (and Germany’s) own polished postwar project of Vergangenheitsbewältigung, which saw the horrors of the Holocaust memorialized with public monuments, Günter Grass novels, and a general attitude of seemingly well-meaning apologism. But such efforts had the corollary problem of mothballing the cataclysm, of making the oft-repeated mantra “Never Again” feel less like a vigilant warning and more like some implicit promise. Jelinek’s embrace of the abject serves as a correction to this official, potentially sanitizing response. She cranks open the release valve for that which is kept within, psychologically and physiologically. To this second point, Jelinek is hyper-attentive to more workaday bodily processes, which are exalted in her descriptions. Here she is illustrating a hiker urinating:

That fellow is pouring himself out completely. And his features are fading more and more, the more he fluidifies himself; it seems he wants to separate himself from his life, this wanderer, by separating from his urinary fluid and, at the same time, also from his seeds…. The other two hikers seem to follow this spectacle of nature with great interest.

In Jelinek’s abject imaginary, taking a piss is no mere routine or simple expelling of wastewater: It’s a draining of something vital and essential. The word pneuma—meaning air, but also connoting, in certain ancient philosophical traditions, the soul—recurs throughout the text. But the pneuma here is not mystical; it is material. It is the very stuff of life, the very blood and bile and piss and shit that sustains us and marks our territory. “Refuse and death,” she writes, “are ours, they show up reliably where we float in the filthy, stinking water, where we and our trash are swimming and drifting…”

For Jelinek, the whole apparatus of human civilization—and modern German civilization specifically—is arranged to keep this stuff hidden or flushed away. Consumerism likewise provides its own shabby cover for the repressed within, carrying with it “the imposition that you must carry your nature inside so that you have room on the outside for your Boss jacket.” Jelinek examines this very nature, in nature. As in Eliot’s The Waste Land, corpses begin to sprout. From the mud and bogs and mass graves, the repressed material of history returns. Before long, that thing that is most repressed, buried six feet deep in the loam of the German subconscious, itself returns, with a vengeance.

The awakening of the unholy trio of Edgar, Gudrun, and Karin proves a mere warm-up. In time, the ground beneath the Alpenrose spits out those “who still were showered to death by us,” those

Millions of dead, simply thrown away by history, a handful over the left shoulder so that they won’t return. Like accidentally spilled salt. Too much pepper is what these dead had in their asses during their lifetime, that’s why they didn’t stay at home. Others traveled to Poland with their cardboard baggage. And there our folks lit quite a fire under their asses.

These bodies, we learn, are victims of the Holocaust, who rise from the earth similarly zombified, nurturing grand designs plotted from their graves. “Now,” Jelenik writes, sounding a bit like a mad scientist egging on her creation, “it’s THEIR turn to rule for at least one thousand years.”

Jelinek borrows from Pynchon an obsession with entropy: the inevitability that all systems will gradually descend into disorder. In 2006, she told an interviewer: “I would say that in our habitual modes of perception entropy serves an increasingly dominant function (as the US novelist Thomas Pynchon foresaw a long time ago).” The Children of the Dead unleashes that entropic force not only on the Alpenrose and the shallow graves surrounding it, but on the sturdier iron of the Teutonic subconscious. But where Pynchon’s World War II epic viewed the Holocaust only in sidelong glances, Jelinek (herself Jewish) keeps her eyes wide open. There is, for the reader, no looking away. Repression, cynical disavowal, and the extensive mental armory of forgetting and flushing away are torn asunder, like decomposing flesh being clawed at by zombies.

On paper, a zombie Holocaust novel sounds about as poor-taste as it comes. But Jelinek’s exploitation of this historical trauma is, if nothing else, knowingly exploitative. For someone reading the book in a period when the trauma of the Holocaust is being grossly wielded to justify genocide, Jelinek’s approach is bracing. She understands it for what it is: a grisly, unfathomable, screeching horror.

Theodor Adorno (whom Jelinek also name-checks in the novel) famously declared that it was barbaric to write poetry after Auschwitz. Poetry, perhaps, but not splatterpunk porno. And as in all instances of the abject, Jelinek’s reflections are as much about the nauseating material as the reactions to it. Her target is not the Holocaust itself, but the psychological and cultural infrastructure erected to keep it at a safe distance. Even these meditations are couched in her typically low humor. “Our Reich,” she writes, “is gigantic because it denies its shortcomings and passes a lot of wind instead.”

In a final, bleak irony, however, most of these realizations are lost on what few living, breathing, still-human characters are left as the novel comes to an end. The true horror of The Children of the Dead does not lie in the throngs of the undead; it lies in the reaction of the living to this uncanny reawakening. That is to say that there is pretty much no reaction whatsoever.

A hostess at the inn futzes around a dining hall, attempting to accommodate the new undead guests. A forester attempts to forestall a looming landslide of mud and dirt and dead bodies that dooms the Alpenrose and the Tyrolean valley below. But otherwise, the vacationing guests of the resort seem basically oblivious to the horrors around them. Jelinek’s sympathies lie with the dead. (That her narrator also seems to be a member of the zombie throng should come as no surprise.) They are, after all, merely “looking for community.” The still-living, meanwhile, seem irredeemably ignorant. This is the author’s most lacerating critique: Not only can genocide be perpetrated with a lack of feeling, but such callousness will also, invariably, mark its monstrous, uncanny un-perpetration. It is here that The Children of the Dead, for reasons well outside its author’s presumed intent and imagination, feels brutally contemporary, at a time when “Never Again” is happening now. The human capacity to bury, repress, and flush away that which is repellent, or merely inconvenient, can outmatch any army, living or dead. “I see nothing.” They never have.

Support independent journalism that exposes oligarchs and profiteers

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Why “The Living Mountain” Endures Why “The Living Mountain” Endures

Nan Shepard’s classic of nature writing and memoir is an education in how to reorient one's attention to a landscape and its lifeforms, human and nonhuman.

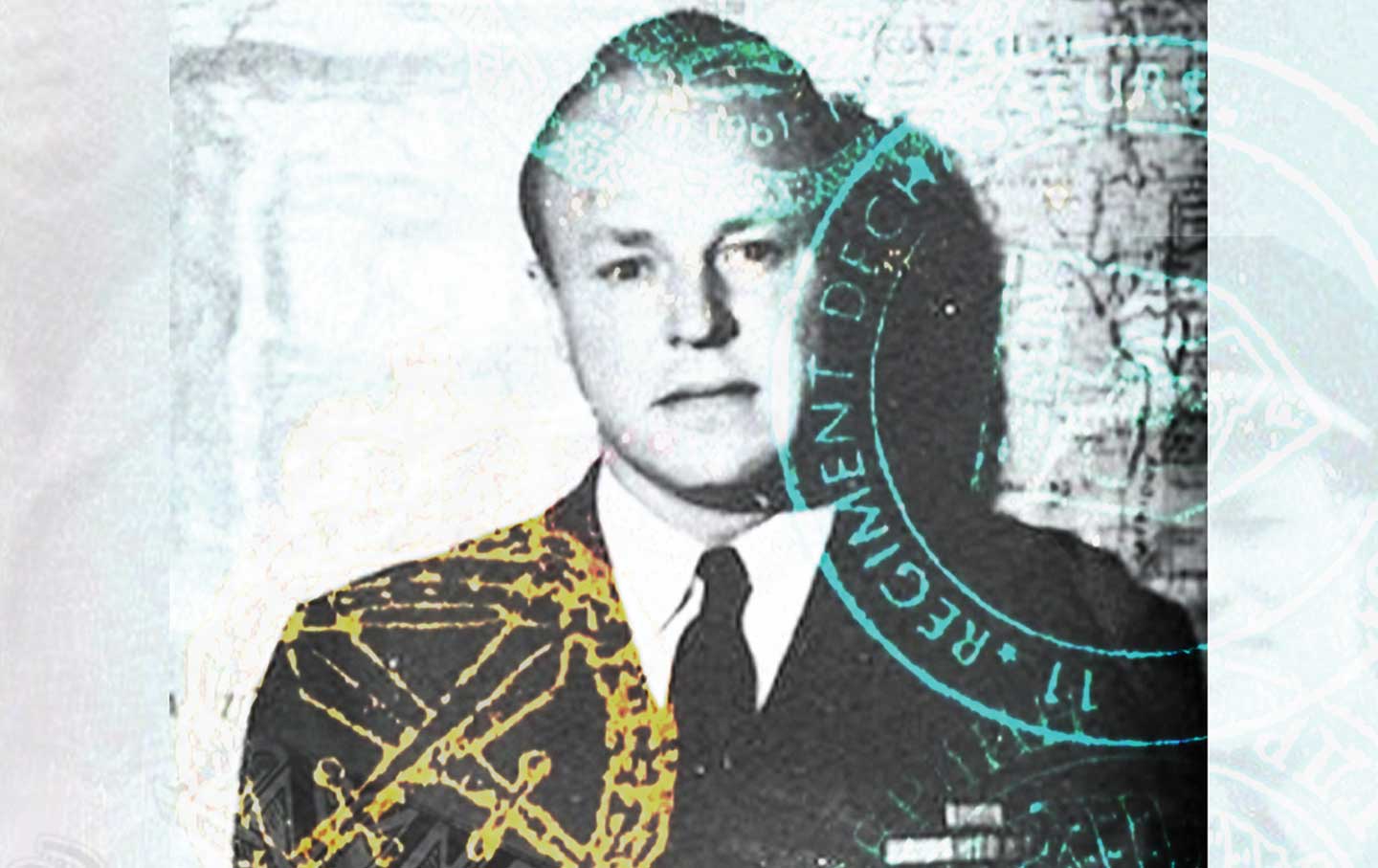

The Making of a Cold War Spy The Making of a Cold War Spy

The life and work of Frank Wisner, one of the CIA’s founding officers, offers us a portrait of American intelligence’s excesses.

The Workplace Nightmares of “Severance” The Workplace Nightmares of “Severance”

The appeal of the Apple TV+ series is how it dramatizes our alienation from labor.

How Atlanta Became a Walkable City How Atlanta Became a Walkable City

The Beltline and Georgia's experiment in pedestrian spaces.