A conversation with Eve L. Ewing about the schoolhouse’s role in enforcing racial hierarchy and her book Original Sins.

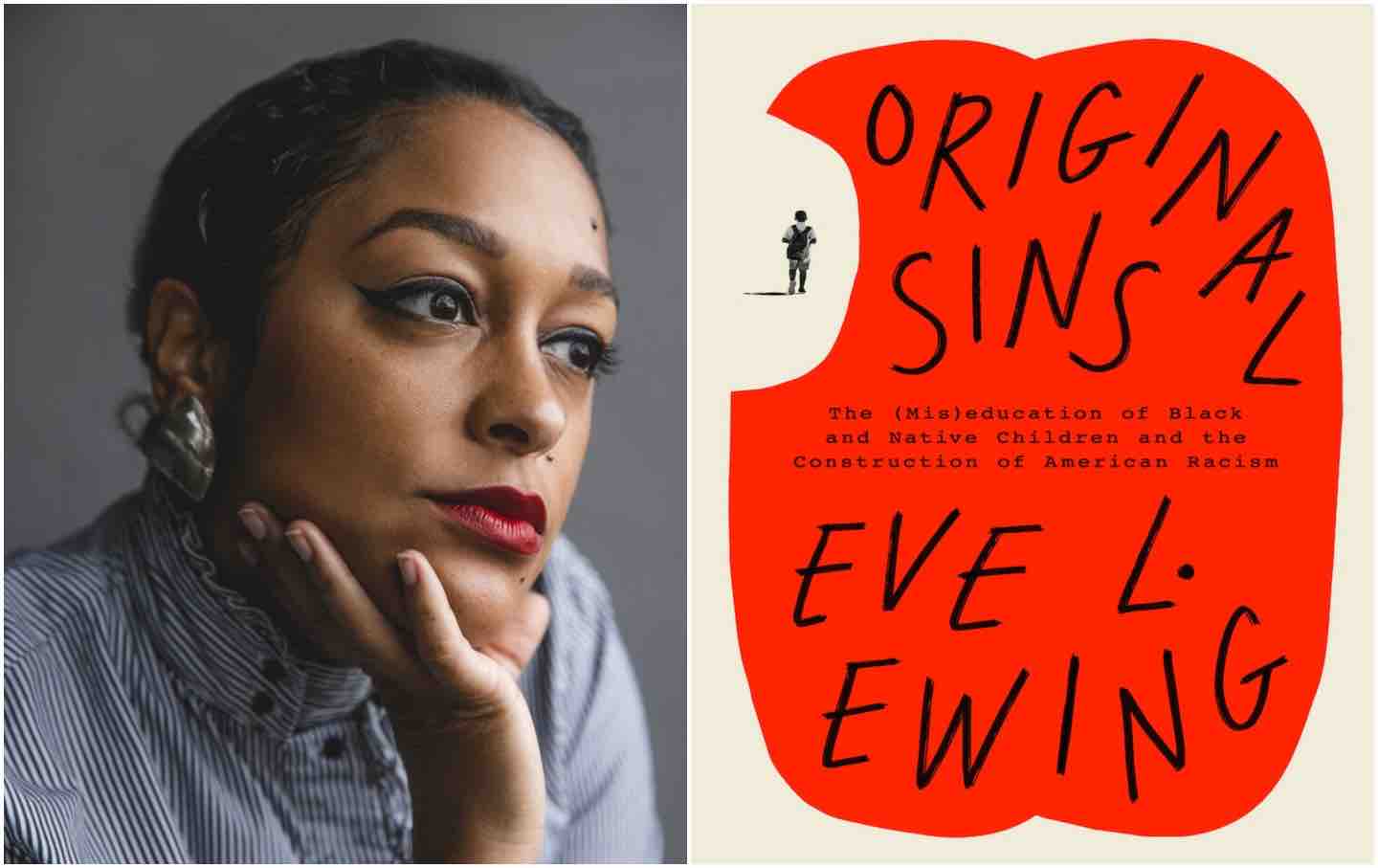

Eve L. Ewing (Photo by Nolis Anderson)

Eve L. Ewing has spent much of her career examining inequities in our educational system, in works such as Ghosts in the Schoolyard: Racism and School Closings on Chicago’s South Side, an in-depth look at a 2013 school policy decision that resulted in mass school closures that disproportionately affected Black communities. In her latest book, Original Sins: The (Mis)education of Black and Native Children and the Construction of American Racism, The Chicago-born educator, poet, and sociologist at the University of Chicago likens her work to the curious walking pattern of the mythical Sankofa, a bird who walks forward while looking back. The book’s focus is on what Ewing calls the “structural afterlives” of America’s two original sins: chattel slavery and the cultural genocide of Native Americans. Its subtitle is a nod to historian Carter G. Woodson’s 1933 book The Mis-Education of the Negro.

Original Sins is conversational in tone but consummately scholarly in its rigor: Ewing uses a mixture of historical research, critical analysis, and experiential evidence from her nearly 20 years as an educator in carceral, elementary, and university settings to demonstrate how the American schoolhouse has functioned as an enforcement agency for racial hierarchies. “Original sin is inherited and structurally fundamental,” Ewing writes. “It doesn’t go away.” As a result, Black and Indigenous freedoms are not only coupled but also profoundly tied to schooling. As the Brazilian philosopher Paulo Freiere once noted, “There’s no such thing as a neutral educational process.” Original Sin explores the consequences of that conclusion, among others, and also theorizes the best practices for harnessing the “deep and furious power” Ewing believes lies within the shared histories of Black and Native Americans that can spawn new, more ethical pathways for learning.

The Nation spoke with Ewing about the ideological agendas furthered by American schools, why it’s important to think not only about how schools work but also what we want them to do, and why understanding that schools are part of complex social systems that include our carceral and healthcare infrastructures is instrumental to improving them. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

—Naomi Elias

Naomi Elias: This book is dedicated to tackling the reasons American schools are broken now. Why do we start, then, with Thomas Jefferson?

Eve L. Ewing: I have felt for a long time, in my teaching and in my writing, that it’s impossible to understand race in the United States without understanding our educational system. And it’s impossible to understand that system without understanding the specific histories that I’m talking about—especially the ways that Black and Native young people have been treated. I hope to make clear in the book that schools are a really important part of creating that racial hierarchy. So it begins with Thomas Jefferson because I want people to understand that the purpose of schools is really embedded in the racialized purpose of the nation, a country that is built on chattel slavery and Indigenous genocide. The republic that we take for granted doesn’t exist without those two social and historical forces. Schools are not outside or incidental to those forces.

NE: When systems don’t work or don’t produce a desired outcome, we believe they’re broken, but your argument is that our educational system is doing what it was designed to do.

EE: To use a contemporary colloquialism, it’s a feature, not a bug.

NE: Could you explain or just outline some of those designs, and how you put this book together to shape that argument?

EE: I started working in classrooms in 2005, and I became a full-time public school teacher in 2008. At that time, and something that continues into the present, is this idea of the achievement gap. And the suggestion, as you point out, is that these systems are broken, they’re not working, and if we just tweak them around the edges, or if we just make a correction here or there, it’s something that we can fix. One of the designs that I highlight is the way in which residential schools—boarding schools for Native young people in the United States—reflect a larger project of schooling for Native youth that was explicitly, intentionally, and transparently designed to play a role in genocidal eradication and land theft.

There are really specific, very transparent times when people like the US Secretary of the Interior and other government officials have said, “We can use schools to fight this war more effectively than we can fight it with guns and soldiers.” And so that’s one historical example. And then another example in the history of Black American education, specifically the schools opened up for freed slaves after Emancipation, which are some of the first universal public schooling efforts that we see not only in the South but in the United States—this effort to provide mass education during Reconstruction.

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation

When one looks at the content of the textbooks that were produced—by and large by publishing companies in the North for dissemination and reproduction in the South—you can glean a specific intention not just to teach newly freed people how to read or how to do math, but to give them explicit moralist narratives that tell them, “Whatever you do, never strike the person who formerly enslaved you. Never treat them with hostility or vengeance; never be angry against them.” This idea really gets pushed to an absurd extreme: There’s one text that I cite where they say, “If the people who formerly enslaved you mistreat you or don’t respect your citizenship, tell them, ‘I have rights.’ And if they don’t listen to you, write your congressperson and let them know that you’re being disrespected.” The idea here is that literally any response is more legitimate and more desirable than the idea that formerly enslaved Black people should be resentful or violent, right?

I’m saying that we should understand these as originary perspectives, and that this is really what schools have been for, for these groups of people, for a long time.

NE: In the course of answering why our education system is broken, you ponder what its purpose is. I hadn’t thought about that in a long time. And you explain how its purpose has evolved over time, often to meet the needs of the country during a given decade or political moment. There’s the example of the late 1950s space race against the Soviet Union convincing President Eisenhower that greater competency in science and math was a matter of national security. What would you say education’s purpose is in this political moment?

EE: As you and I are talking right now, we are looking ahead to what the next presidential administration is going to look like, and by the time this is published, we’ll already have a little bit of a sense of it. But there are also certain things that we know we can expect. A lot of the conversation that has been happening around censorship, book bannings, what content should or should not be allowed to be taught in classrooms, and the way that the Trump administration wants to curtail that and control that, I think it’s really easy, because the idea of individual freedom is so central to American ideology. It’s really easy for us to focus on these questions of curriculum as questions of individual freedom, free speech, and First Amendment rights—the rights of individual authors to have their work disseminated, the rights of individual teachers to do individual things.

As with everything that the Trump administration does, part of the tactic is always to overwhelm you with such a deluge of policies that are so awful that it becomes hard to even understand where to begin. That’s a tactic that makes it hard to zoom out and see the bigger picture. But if we do zoom out and see the bigger picture, we should see these efforts at repression as not merely a matter of individual censorship or of individual rights being curtailed, but as a broader ideological agenda of using schools to normalize and perpetuate fascism, and using schools to normalize and perpetuate the prevailing political agenda, in which people are less empowered to speak out or to act critically against government authority—not only for fear of reprisal, but also because the goal is to raise a generation of young people that doesn’t even have the kind of intellectual schema or conceptual framework to understand what resistance looks like.

We should understand these efforts at curtailing what people learn as efforts to diminish the critical capacity of young people to stand up against authoritarian governance. Now I have nothing but faith that critical thinking and social critique and historical awareness will always prevail in the way that they always have. Still, it’s important for us to see that bigger picture and not get caught up in just the curtailing of people’s individual rights.

NE: Obviously, Trump campaigned and won on the promise of Project 2025, which is targeting one of the biggest school policy decisions in American history by terminating the Department of Education. And as you’re saying, it remains to be seen whether this is his usual bluster or an achievable goal or priority. Still, how are educators preparing for Trump to attempt to fulfill that promise? What is the conversation among your peers?

EE: Again, this tactic of overwhelming, of flooding the field, can be really effective, and my personal analysis—and I’m willing to be wrong here—is that I don’t think we should ever assume anything Trump says is bluster. I think he fully has the intention to do these things, but to a certain extent, the functioning of the Department of Education in the US educational system is largely state-based and federalized. And because people really like the idea of local control and being able to make sure that what education looks like in Massachusetts is different from what education looks like in Oklahoma or Texas or North Dakota, the Department of Education as it currently exists has—compared to many of our peer nations—a pretty limited ability to direct what actually happens on a day-to-day level in schools.

For most educators, the fact of how and why the department functions is important, but in a way, what Trump’s message really does is say that nothing is sacred in the functioning of US public education. It’s the normalization of this authoritarian action that is in line with this presidential leadership team’s general disregard for any kind of civic normalcy. It’s in line with other things like people having to look ahead and question whether the basic things that they’ve come to rely on will be there, like “Will I be able to access this kind of gender-affirming medical care if I’m not in a heterosexual marriage? What are the rights going to be for me to be with my partner in the hospital, or for me to have custody of our children?” It drives people into a sense of fear and uncertainty when they can’t count on the basic realities of the world that they live in, that they’ve come to take for granted.

Get unlimited access: $9.50 for six months.

And that, in turn, makes people frightened in ways that can stifle political action and political resistance. So it’s really important for educators, but also for people generally, to think about the best ways for surviving, thriving, resisting, critiquing, building, and maintaining the world we want. That includes protecting the people that we love, protecting our families and vulnerable members of our communities, keeping that at the center and letting that desire drive our action, rather than being pulled into the abyss of reacting to whatever absolutely bananas proposal is being put on the table next.

NE: So many teachers will get on social media or talk to national magazines about how their students struggle to even finish a book, and professors are worrying about ChatGPT showing up in college papers, and there’s this overwhelming fear that American children and teens and young adults are not learning. Do you think the bigger problem is miseducation or undereducation?

EE: They’re connected. Again, the question is: What do we want our schools to do? Those lamentations from teachers reflect two different things that we want our schools to do. We want schools to provide young people with the basic skills that they need to survive and thrive in our society. We want young people to be able to read—and I would argue not only to read mechanically, but also to find joy in reading, for literature to be a source of agency, autonomy, joy, and meaning. We want young people to be able to do math—but we should want them, more importantly, to use quantitative reasoning and analysis to better understand the world around them.

What I’m alluding to there is that we want schools to teach young people basic skills, but we also want them to be places where they can find community, meaning, purpose, and a sense of fulfillment. And also to feel loved, to be nurtured, to feel like they’re part of something. Sometimes we can talk about those two purposes as though they’re at odds, or as though it’s easy to focus on one and forget about the other. But I believe that it’s really hard to do the kind of intellectual and skills-based work that we’re asking young people to do, and that we’re asking teachers to lead, if you don’t have the foundation of feeling safe, feeling loved, feeling celebrated.

When I was a middle school teacher, and I had to explain what a fraction is—not just how you multiply fractions, but what a fraction is—or what the earth is and what it means to be living on a planet in space, or the basic moral or ethical questions that you have to untangle when you read a book like To Kill a Mockingbird or Romeo and Juliet, that work (on an intellectual level, on a level of cognitive demand) was some of the most challenging I’ve ever had to undertake in my life. So I think that it’s really important for understanding the converse of that. The cognitive load is actually pretty tremendous. It requires a foundation of safety and care that we can’t separate out.

NE: A Pew study from spring 2024 found a little over half of American adults think our K–12 system is going in the wrong direction. A significant number of Democrats and Republicans agree on that, but with differing opinions about why that is and what remedies to pursue. It just feels like a stalemate. And education feels like a really important thing to be paying attention to right now because, as you explain, it’s so central to what our goals are as a nation.

EE: There’s a funny thing that happens in education that is different from other areas of perpetual social crisis, like housing or economics or healthcare. There’s a kind of basic disregard for education as a highly specialized or complex social system—both because it involves children, it involves care work, and because it’s also something that everybody has experienced as a participant.

But we can’t understand the education crisis as just about what is happening in schools or not happening in schools, because it’s part of a set of complex social systems that is integrated with everything from the criminal legal system, to the lack of affordable housing in the United States, to mental health crises. Education, because it involves children, because it’s largely women who are in the labor force, and because it’s something that people think they know—”Well, yeah, I was in school once,” right?—for all those reasons, its interrelatedness to other social issues is ignored. I think that is a mistake.

Naomi Eliasis a writer based in Los Angeles. Her work has appeared in The Brooklyn Rail, Longreads, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere.