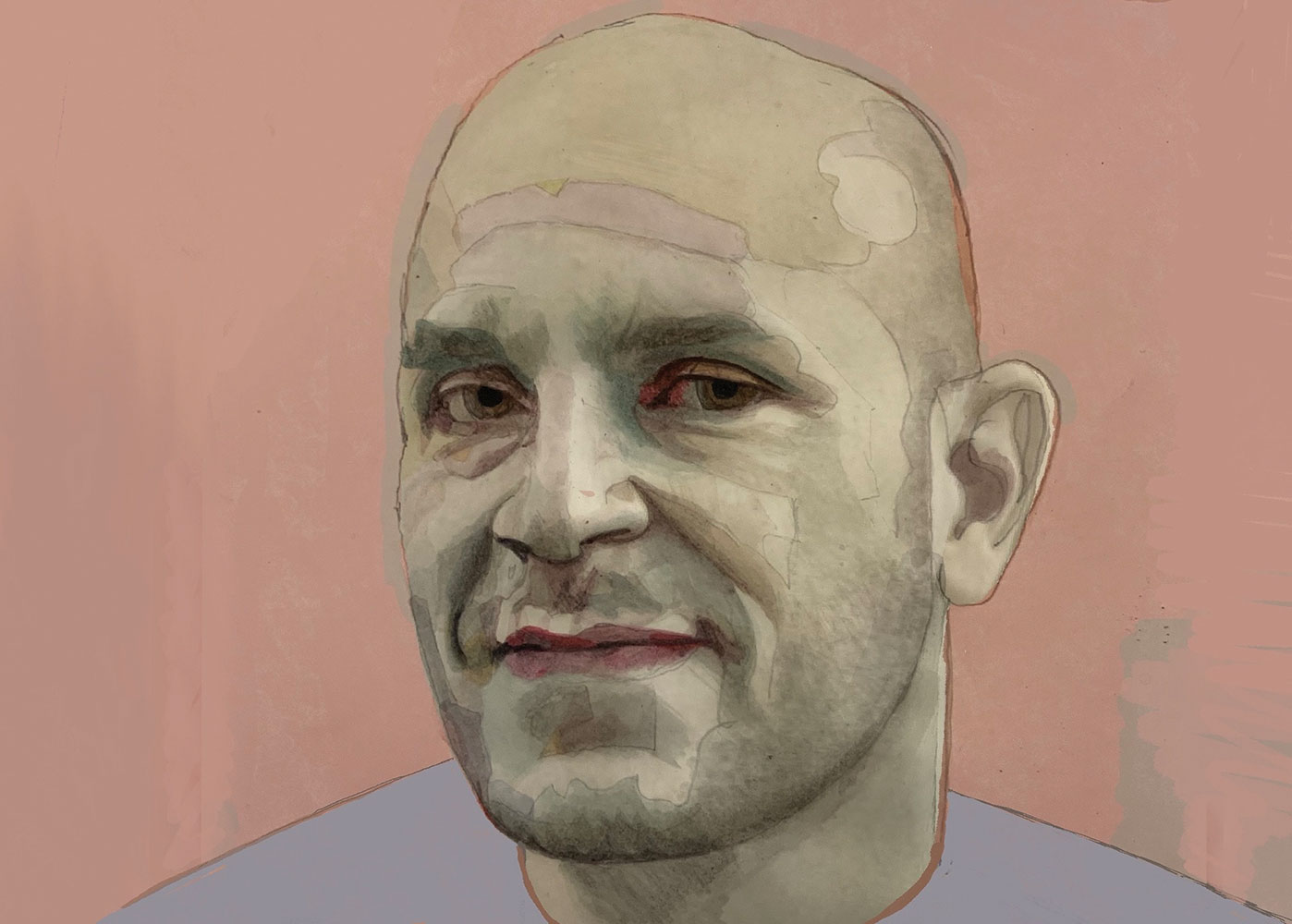

Hallways of Dislocation

The poetry of Fady Joudah.

Fady Joudah’s Poetry of Dislocation

In his new book of poetry, […], the poet, translator, and ER doctor explores Palestinians’ experiences of exile and displacement—and the difficulty of healing amid the ongoing Nakba.

Being alone and helpless in a hospital corridor —adrift between rooms, shifts, and diagnoses; stripped of one’s property and power, just a name among many others—is the closest that many of Fady Joudah’s American readers may come to understanding the kinds of dispossession that Palestinians have experienced for nearly a century. Lost in the labyrinthine bureaucracy of a cumbersome medical system, with few possessions and limited agency, the hallway patient is forced to justify himself again and again, to explain why he is there, what he needs, what belongs to him. Wheeled from corridor to ward to corridor, he has no permanent place to rest. Nurses come and go abruptly. Just as the patient thinks he has found a somewhat sympathetic doctor, that doctor’s shift ends and another arrives. The new one shows even less interest in his malady. The patient loses all patience when he sees that the doctor is concerned only with treating superficial symptoms rather than addressing the deeper cause.

Books in review

[…]

Buy this bookJoudah—an ER physician and a translator, the child of exiled Palestinians, and for some time now a highly accomplished poet—has long illuminated the ways in which this state of convalescence resonates with his own life and that of his family. For the Houston-based polymath, the indignities of the extractive, for-profit hospital system that he sees his patients caught up in serve as a microcosm of the state of being a refugee, of living in exile with neither rights nor a voice—at least not one that is heard. As Joudah told the Houston Chronicle in 2008, when his first book of poetry, The Earth in the Attic, was published, his poems have long allowed him to bring attention to the harrowing experiences of dislocation that he observes both in hospitals and among his Palestinian family and friends. “For me, being a physician,” he added, it was impossible not to see that “patients are displaced people, at least momentarily.”

In his new volume of poetry, […], published more than 15 years after the first, Joudah retains his focus on the questions of dislocation but now directs his attention to the impossibility of healing amid the protracted and ongoing Nakba. If hospitals and the Palestinian condition once served as metaphors for each other, they now belong to the same literal story: the latest phase of the genocide in which Israeli warplanes and soldiers target hospitals, doctors, nurses, ambulances, and Red Crescent vehicles.

Alongside dislocation are the horrors of a war in which the very people who bring healing to the pained and suffering are themselves wounded or killed. While “not everyone / is a physician,” Joudah reminds us in one poem, “sooner or later everyone / fails to heal.”

This grim reminder is just one of the themes in […]. Others include the need for as well as the difficulties of mourning. “We need to differentiate / between the dead and the not here,” Joudah writes, and yet he notes that this, too, is often impossible. Many are either buried beneath the rubble or have been vaporized by the heat produced by bombs. How can one grieve if all the traditional places of mourning, such as grave sites, don’t exist? How can one grieve when funeral rites—which finalize the separation between the living and the dead—cannot be held?

In this unprecedented assault on not just the living but also the dead, corpses are confiscated, graves desecrated, and entire families killed off so that there’s no one left to mourn them. “Suddenly you / can’t find my body / can’t bury / what you can’t find,” Joudah writes. He reminds us that mourning is itself a luxury that few Palestinians can afford, and that there is no “P” in “PTSD” for a people repeatedly and routinely subjected to violence.

Beyond these keenly observed and beautifully rendered descriptions of Palestine’s tragedy, Joudah’s poems offer a startling diagnosis of our narrowing political horizons and even a prognosis for how we might act within them. Of the many things that have perished in Gaza besides human lives—international law, morality, the myth of the civilized West—it is the death of language that Joudah grieves most: “From time to time, language dies. / It is dying now. / Who is alive to speak it?”

This death of language is also the death of politics and the many avenues we have for imagining it. If language itself is being annihilated, Joudah’s poems challenge us to ask, what is the function of speech in a time of such untold suffering? What can language do when the sight of mutilated bodies doesn’t jolt us into action but instead numbs us into indifference? In […], Joudah’s central and counterintuitive claim about the death of language isn’t so much about the absence of speech—its silencing, muzzling, or muting—but its surplus. The one who “gets to write it most,” he asserts in one poem, is the one who “gets to erase it best.” A surfeit of words can work as an analgesic—even as anesthetics are prohibited from entering Gaza—and logorrhea, like aphasia, is a symptom of an unnameable malady that causes “ineffable suffering.”

In […], Joudah points to other logical contortions that define the Palestinian condition. But he does so while emphatically refusing to play the role of native informant. Earlier, through his English translations of Palestine’s preeminent poet, Mahmoud Darwish, Joudah helped to introduce Palestinian poetry into the canon of American letters. Now, in this time of genocide, he refuses that role altogether. “I am not your translator,” he declares in one poem, echoing James Baldwin’s “I am not your Negro.” As a Palestinian writing in English, “I am not a cultural bridge between the vanquisher and the vanquished.”

Joudah instead seeks to transcend the demands persistently made on him, while still trying to demonstrate his and his people’s suffering. Rejecting the obscene demands made on exhausted, grieving diasporic Palestinians to provide evidence of their very humanity to deadened audiences who often refuse to regard them as such, Joudah focuses his poems elsewhere. Although reality “isn’t hard to see,” he notes in one stanza, we live in “a world that doesn’t” appear to see it.

This latter point was driven home by the sight of delegates at the Democratic National Convention this past August covering their ears to shut out a recitation of the names of Palestinians killed in Gaza. And Joudah addresses and dedicates his new collection “to the martyrs who did not furnish their photos for their killers to air them on their compassionate TV. To the martyrs who did not speak English. To the relatable and unrelatable, the translatable and untranslatable Palestinian flesh.” Such flesh must be honored, even—and especially—when it cannot be “translated” into words that speak to his American readership’s political concerns.

In a way, […] breaks with previous generations of diasporic Palestinian writing and activism, especially as exemplified by Edward Said’s Orientalism. While those earlier generations wagered that in order to change the world, one had to describe it differently, Joudah worries that such a redescription no longer will be enough. The fantasy that if we had more accurate information and better representation—of greater precision and specificity, less based in crude generalizations and stereotypes—we could flatten the asymmetries of power and effect empire’s undoing no longer appears to suffice amid the ruins and rubble of Gaza.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Yet in Joudah’s pessimism about the value of such attempts, he finds the freedom to do something much more affecting and perhaps more tactically effective. Instead of trying to dismantle the usual myths and stereotypes that structure the imperial perception of the Palestinian people, he points to the logical contradictions that underpin those ideas. For example, he asks, “Shall I condemn myself a little / for you to forgive yourself / in my body? Oh how you love my body / my body, my house.” By drawing on mystical tropes and aphoristic forms, he tries to undermine the foundational antinomies of liberalism (private and public, enemy and friend, religious and secular, and so on). And in a very different way—and perhaps a more effective one—he also tries to undermine the presuppositions that buttress so much of the global support for Zionism and the political dispensations that enable it.

Perceiving both that liberalism’s contradictions are central to the making of the genocide and that those same contradictions contain the seeds of its potential unraveling, Joudah reminds us that language is endlessly promiscuous and unsettling, that it constantly evades the intentions of those who hope to stabilize it. This is why, at his most brilliant, Joudah deploys the aphorism to such startling effect: “A free heart within a caged chest is free.”

Reading […], one is struck by how many of its lines are devoted not just to the victims of displacement and extermination but to the perpetrators. Writing to the oppressors “who remove me from my house,” Joudah asks why they are incapable of seeing “what’s being done / to me now by you.” So delusionally convinced are they of their own victimhood, he observes, that they are unable to see how the poem’s dispossessed speaker is “closer to you / than you are to yourself / and this, my enemy friend / is the definition of distance.” Joudah does not deny the sense of victimhood of these oppressors and even attempts to inhabit it poetically, if only fleetingly, allowing the antinomy between enemy and friend to momentarily fall away. “Aggressors also grieve,” he reminds us in one of the many lines that straddle the sardonic and the empathetic.

But this attempt to inhabit the mind of the perpetrator isn’t done in the name of liberal coexistence; rather, it is meant to serve as a sharp reminder that historical victimhood doesn’t give Zionists a license to inflict cruelty on others. It also doesn’t give them a unique capacity to understand suffering—if anything, it inures the historical victims of violence to their own brutal acts.

While there is an intimacy to the way that the oppressed know their oppressors, this familiarity, Joudah insists, is seldom requited. The oppressors can continue to refuse to recognize not only their victims’ humanity but how those victims are intimately tied to, and even produced by, them. In […], Joudah shows his readers how, in this way, Palestinians have become the true heirs of the Holocaust. Not only did the catastrophic dispossession that Palestinians have experienced—and continue to experience—in the Nakba mirror that catastrophic dispossession of the past, but it was also in some ways made by it. “My catastrophe in the present,” Joudah writes, “is still not the size of your past,” yet it exists nonetheless and will one day, too, become a part of history, when its magnitude shall finally be appreciated. Even when indulging the oppressors in their own sense of injustice, Joudah’s words are a shocking reminder of the asymmetries of empathy and therefore power that underwrite colonial relations.

Several critics have already commented on the ineffable title, both literally and figuratively, that Joudah has chosen for […], which is also the title of a large number of its poems. This apparent redaction of the book’s very name evokes the McCarthyist silencing of Palestinians in Europe and North America, and it also summons the redacted documents from the War on Terror that obscured the torture of extradited prisoners in the United States’ military bases and colonies.

But perhaps most powerfully—and this is especially pertinent for Joudah, who has lost scores of family members in the most recent phase of the genocide—the title evokes the flashing digital ellipsis that appears on phone screens as one waits for a response from a loved one that—in the case of those who have family or friends in Gaza—often never comes. Over the past year, Palestinians on social media have posted screenshots of the messages they sent that were never read, or those that were read but never received an answer because their recipients had been killed.

I read the title as doing something else, too—something as much political as poetic. The redaction and the ellipsis belong to an economy of refusal, one that must be understood alongside the boycott as a strategy that highlights liberalism’s contradictions and, in so doing, undermines them. As Joudah explained in an interview after […] was published:

Listening to the Palestinian in English does not mean that the Palestinian is always talking. We also need to learn how to listen in silence to the Palestinian in their silence. So far, when a Palestinian goes silent, it means they are dead or violable, digestible, liable for further erasure or dispossession. English has not begun imagining the Palestinian speaking, let alone understanding Palestinian silence.

The elliptical redaction that gives the volume its title is a gesture toward the freedom to speak, yes, but perhaps more important, also one seeking the freedom to be silent. In the early weeks of October 2023, a veteran Palestinian organizer told me: “We have been fighting these battles for 73 years; we’ve laid the groundwork for everyone. We’ve spoken at rallies, written articles, organized on campuses. We are tired; we are grieving. It’s time for the global left to carry the baton for us now.”

While all of us need to get better at listening to Palestinians—to their analysis of the past and their diagnosis of the future, to what they’ve described for decades and what they have cautioned us about for just as long—we must also be careful of our own motivations when we “center Palestinian voices,” lest such a demand become a way of evading our own culpability. We who financially sponsor or give cover to the genocide must also step into the silent gap offered by Joudah’s […] to articulate our own subject position as perpetrators, to not just call for Palestinian liberation but seek to realize it.

“I am removing me,” Joudah tells us, “from the we of you.” It is that “we” which is left behind that must confront the moral chasm in ourselves—facing our monstrous societies and states that add to the grief of the already anguished Palestinians.

That what happens in Gaza shall determine our collective futures, wherever we may live, is increasingly obvious. How can we redistribute the struggle that has fallen for far too long on the suffering shoulders of Palestinians? By forcing us to listen to the silence in […], Joudah puts this question to us all. If the future is unimaginable, the present intolerable, and the past forbidden, then Joudah’s verses address us all in the future perfect: “I write for the future / because my present is demolished. / I fly to the future / to retrieve my demolished present / as a legible past.” Even in their silence, these poems present us with a deafening call to act.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Best Albums of 2025 The Best Albums of 2025

From Mavis Staples to the Kronos Quartet—these are our music critic’s favorite works from this year.

Forrest Gander’s Desert Phenomenology Forrest Gander’s Desert Phenomenology

His poems bridge the gap between nature’s wild expanse and the private space of one’s imagination.

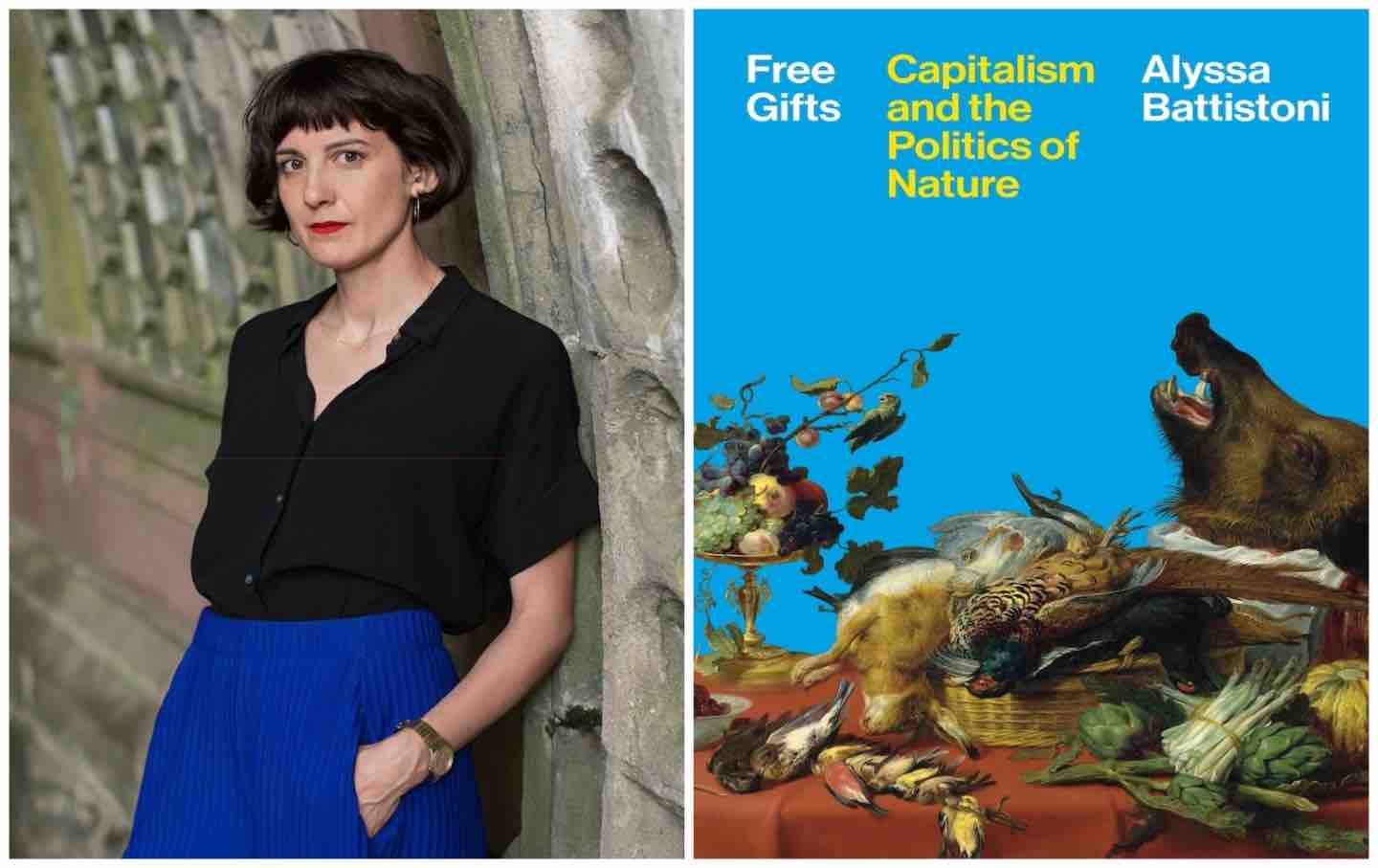

Capitalism’s Toxic Nature Capitalism’s Toxic Nature

A conversation with Alyssa Battistoni about the essential and contradictory nature of capitalism to the environment and her new book Free Gifts: Capitalism and the Politics of Nat...

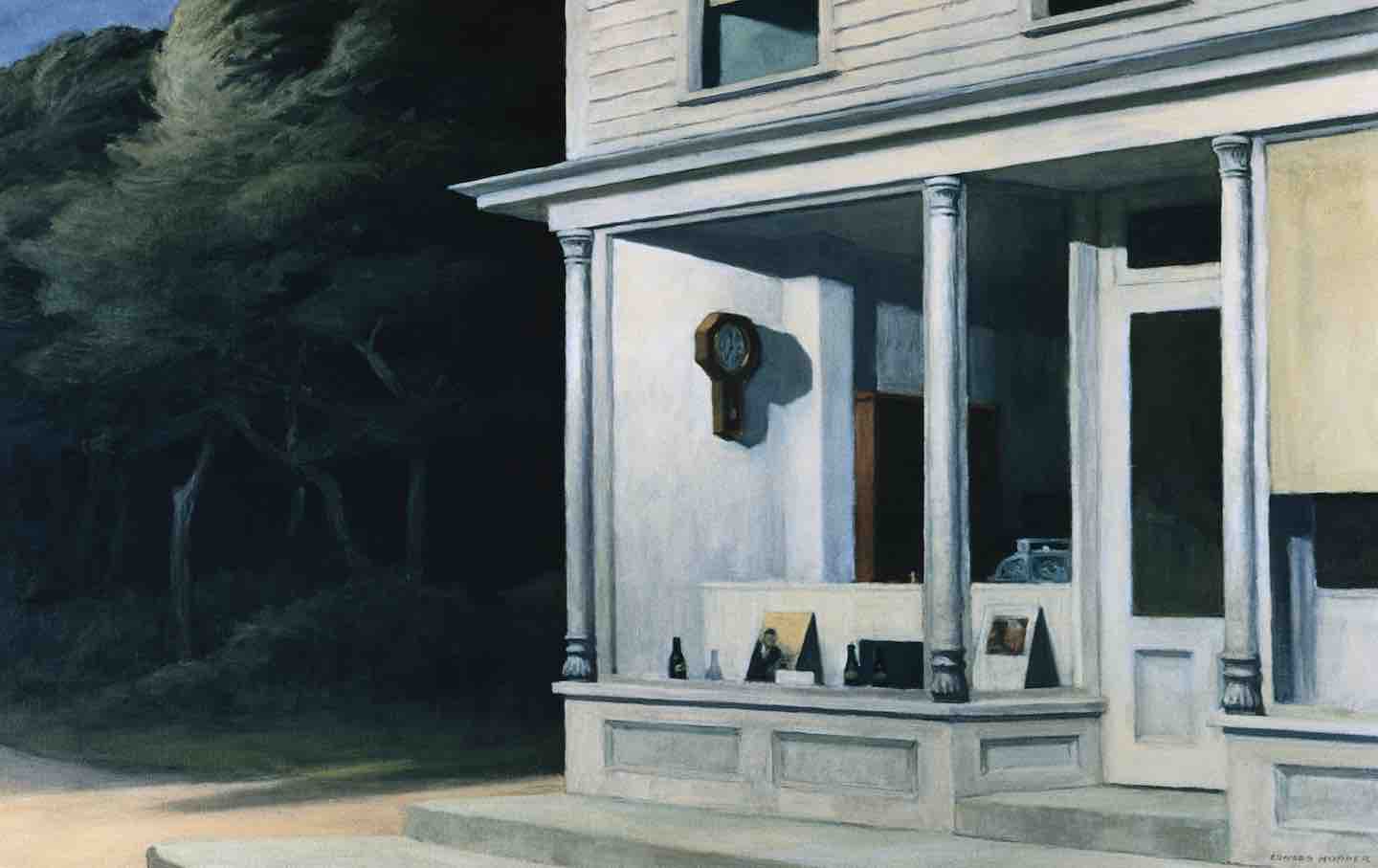

Solvej Balle and the Tyranny of Time Solvej Balle and the Tyranny of Time

The Danish novelist’s septology, On the Calculation of Volume, asks what fiction can explore when you remove one of its key characteristics—the idea of time itself.

Muriel Spark’s Magnetic Pull Muriel Spark’s Magnetic Pull

What made the Scottish novelist’s antic novels so appealing?

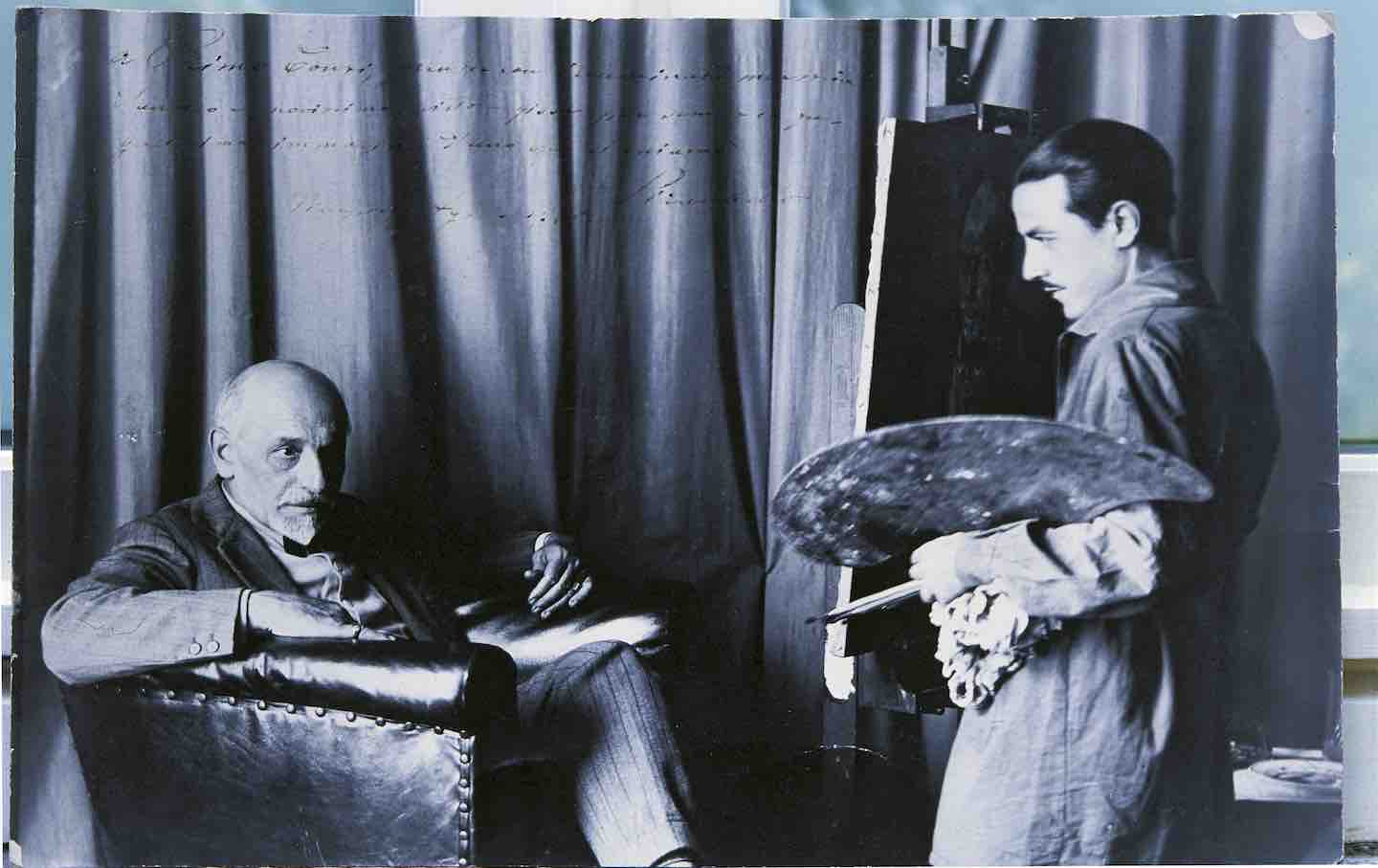

Luigi Pirandello’s Broken Men Luigi Pirandello’s Broken Men

The Nobel Prize-winning writer was once seen as Italy’s great man of letters. Why was he forgotten?