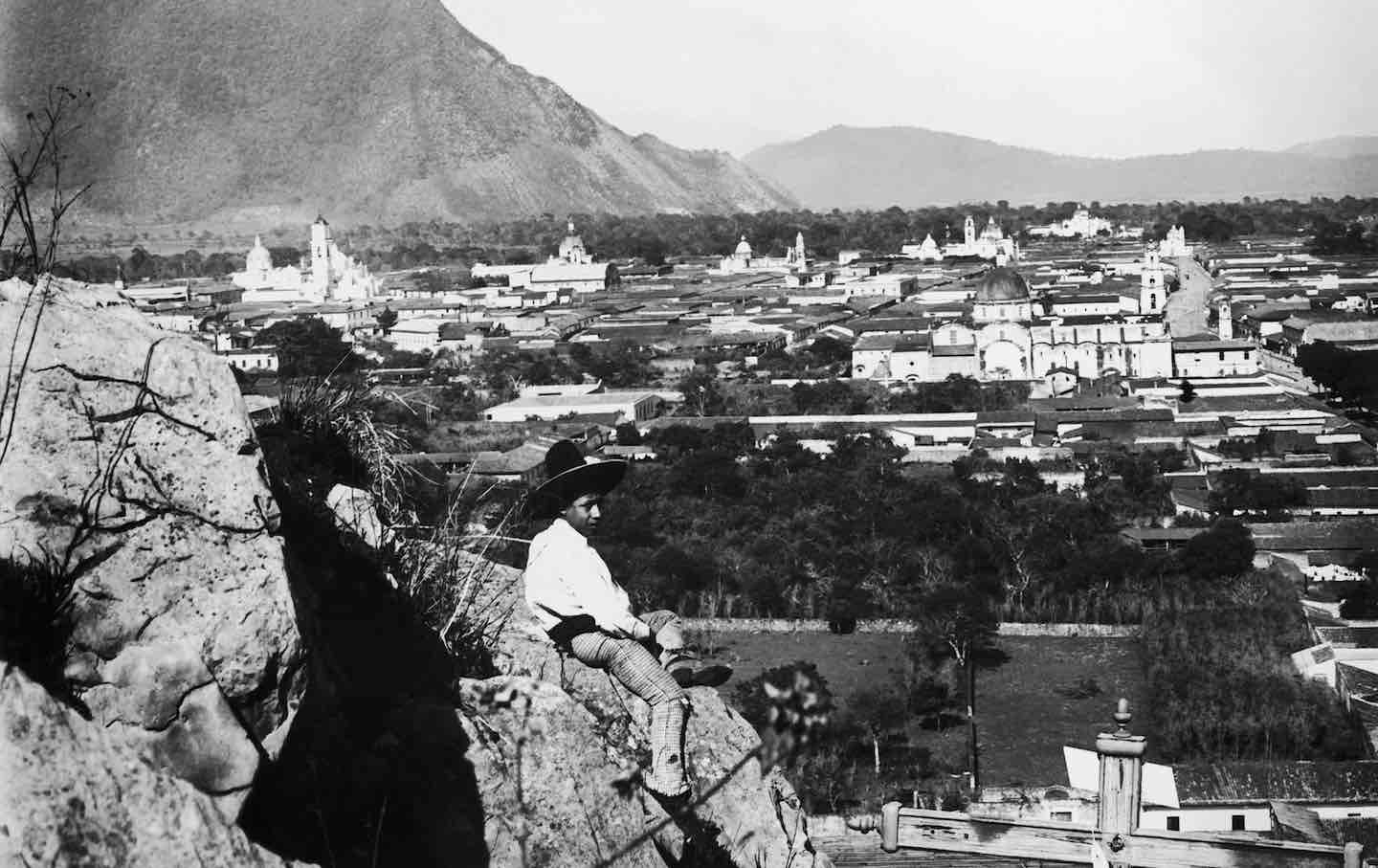

Orizaba, Veracruz State, Mexico. (Photo by Keystone-France / Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images)

In the opening essay of This Is Not Miami, Fernanda Melchor revisits her childhood obsession with a Spanish-language tabloid called Unusual Weekly. It was a “veritable encyclopedia of shock and horror,” she writes, “a prayer book devoted to monstrous humans and full of blatantly doctored photos.” In the same piece, Melchor says she felt grateful that a solar eclipse that occurred when she was 9 hadn’t been visible from her home; she knows she would never have been able to keep from staring straight at it. This attraction to danger and the morbid would follow Melchor from youth into adulthood and a career spent exploring the darkness at the heart of humanity. No matter the horror, Melchor can’t help but stare.

First published in 2013, This Is Not Miami (translated into English by Sophie Hughes) gathers accounts of violence and crime in Melchor’s home state of Veracruz, Mexico. She trains her eye on its seedy ports and nightclubs, its haunted houses, and, above all, its brutal drug war. Melchor, who began her career as a journalist, wrote these pieces between 2002 and 2011, publishing some in the Mexican cultural magazine Replicante. While many fall within the crónica genre, a hybrid form combining journalism with the stylistic conventions of fiction, Melchor refers to others simply as relatos, or “accounts.” As with her monumental second novel, Hurricane Season—the tempestuous tale of a murder in a fictionalized Veracruz—Melchor’s nonfiction writing and reportage fixates on violence and, more notably, how that violence is told.

Writing for the Los Angeles Review of Books last year, Marcus McGee suggested that to best understand Melchor’s writing, readers should consider her work alongside that of the late Enrique Metinides, Mexico’s legendary nota roja photographer. Throughout the course of his decades-long career, Metinides took thousands of pictures of brutal and bloody tragedies in Mexico City: car crashes, plane crashes, fires, suicides, electrocutions, murders. Often riding in the back of an ambulance, Metinides arrived so quickly on the scene that he seemed like a harbinger of doom. He became synonymous with Mexico’s “red press,” which is known for graphic photographs and lurid headlines.

But, as McGee noted, the photographer would eventually surpass, or at least complicate, the genre’s crude sensationalism. “His camera discloses a concourse of gazes, some staring at the body, some head-on at the camera, others out into space,” he writes of Metinides’s penchant for documenting the onlookers in his photos. McGee compared the two artists while reviewing Melchor’s 2022 novel, Paradais, but the pairing is just as useful when reading her nonfiction. Metinides asks why we’re so compelled by scenes of crime and disaster; Melchor asks what effect these incidents had on the people who witnessed or experienced them. Faced with tragedy, Melchor holds a steady gaze, focused tightly on the individual; rather than give a bird’s-eye view, her instinct is to always get closer.

People are drawn to violent and unhappy stories not only because of morbid curiosity, but also because they lurk beneath quotidian experience; violence and death are merely a part of everyday life. Many of the pieces in Melchor’s collection begin with someone going about an uneventful day, working a tedious job or driving across town, only to be interrupted by a drug shoot-out or a revenge plot. Other stories are so horrific—like a woman who reportedly killed and dismembered her two young children, or a village that enacted savage justice against a rapist—that they demand to be told and retold, eventually calcifying into lore. As either a documenter or a teller of a tall tale, Melchor manifests a sense of foreboding, a reminder of the sickening possibility that one’s life may turn into a tragic story that other people tell.

Yet there’s also a sense of reclamation in how Melchor chooses to tell these stories. In a country where corruption runs rampant, where the official story from the police or the government is tainted, inadequate, or missing altogether, This Is Not Miami functions as a counternarrative: Melchor presents a corrective simply by getting close to her subjects and telling their stories one by one, often in their own voices. Rather than coming from the top down, these stories are transmitted at the ground level; it’s not difficult to imagine Melchor sitting in a yard or a bar, leaning in to listen to her interviewees. But just as a photograph can’t make an argument, the writer refrains from directly explicating her subjects. True to their form, these relatos and crónica are closer to sketches than full-fledged essays; their broader implications are often left to the reader’s interpretation. Refusing to “enter into discourse with History with a capital H,” as Melchor puts it, she lets her subjects speak for themselves.

In “The House on El Estero,” Melchor’s future husband recounts a possession he witnessed. Though the story is engrossing on its own, Melchor is most drawn to his manner of telling it: “He wove together snippets of dialogue, gestures and his own views, both past and present. A typical Veracruz guy, I thought, captivated; a raconteur of manly exploits, trained within a culture that mocks the written word and dismisses the archive, preferring testimony, oral and dramatic accounts—the joyful act of conversing.” This could describe the prose style of Hurricane Season or Paradais, where the characters’ voices saturate the page in long, galloping sentences packed with asides and slang. By contrast, the writing in This Is Not Miami is, with a few notable exceptions, tempered and more functional. Reading these books in the order in which they were published in English—Hurricane, then Paradais, then Miami—makes the collection seem not unlike a musician’s B-sides compilation. It may not be the most powerful manifestation of the writer’s thematic or stylistic concerns, but one can see the building blocks for her greater works. This Is Not Miami makes clear just how grounded the heightened drama of Hurricane Season and Paradais is. The connections between Melchor’s fiction and nonfiction go beyond the subject matter—poverty and superstition, misogyny and sexual violence—and include how a story can be corrupted as it passes from person to person.

In 1989, former Veracruz Carnival queen Evangelina Tejera Bosada was arrested and later convicted for the grisly deaths of her two children. The 2- and 3-year-old boys had been bludgeoned to death, then dismembered and buried in one of their mother’s large plant pots. “Queen, Slave, Woman” focuses on the incessant gossip and salacious media coverage surrounding the case. (Melchor admits to rewriting the original version to make it, in her words, “more comprehensive” and “less biased.”) Despite the doubts of some journalists concerning her guilt, the tabloids branded Tejera Bosada as a “mythical villain, a fairy-tale witch.” Just six years prior, the society pages had painted the young carnival queen as a “living symbol of the joyfulness, vitality, and fecundity of Veracruz’s people.” Melchor writes, “[These are] contradictory yet complementary archetypes. Masks that dehumanize women, acting like blank canvases on which to project the desires, fears, and anxieties of a society that professes to be an enclave of tropical sensualism but deep down is profoundly conservative, classist, and misogynist.” Both drawn to and critical of her country’s sensationalist tabloids, Melchor recognizes that there’s nothing pure or sacred about the act of storytelling, and that stories involving great horrors, if told carelessly, can become a secondary site of violence.

Midway through Hurricane Season, a 13-year-old runaway finds herself being followed by a group of narcos trying to coax her into their pickup truck. A new friend warns her not to go with them, explaining that the narcos work for a man who does “evil, evil things” to girls. More important, he says, is that she should never ask the police for help either: “At the end of the day they were basically the same thing.” In the moment, the line reads as tossed off, one of the novel’s many asides. Later, though, we’ll see (or, rather, hear) the police beating a confession out of a young man. They’re not after information that might solve a crime; instead, they’re trying to find a stash of money and jewels that they plan to seize for themselves. Though each character in Hurricane Season is compelled by more immediate problems, violence (doled out by the cartels or the so-called agents of law enforcement) looms in the air.

Drugs appear throughout This Is Not Miami too—coked-up partiers, narco planes mistaken for UFOs—but it’s not until the book’s third and final section that Melchor more directly depicts the pervasiveness of the drug war in Veracruz, and the way its accompanying brutalities permeate life there.

Melchor says she wrote most of the pieces in This Is Not Miami while Fidel Herrera was governor of Veracruz (2004–2010) and Felipe Calderón was president of Mexico (2006–2012)—two administrations that, she says, “overlapped to disastrous consequence.” Herrera, though never charged with a crime, is said to have embezzled public funds to line his own pockets. During his gubernatorial campaign, he allegedly accepted millions of dollars from Los Zetas—one of the most powerful cartels in Mexico at the time, known for its savagery and paramilitary structure—all but ensuring his cooperation throughout his term. He allegedly got so cozy with the cartel that they referred to him as “Zeta 1.” And just 10 days after Calderón’s victory in a highly contested election, his administration declared war on the cartels, setting off a period so violent that Mexico’s murder rate soon doubled.

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation

Given that many of the pieces in This Is Not Miami originally appeared in Mexican publications, Melchor keeps this broader context off the page; her readers would not have needed any of this explained. Herrera’s relationship with Los Zetas was an open secret in Veracruz, and government officials accepting money from the cartels was considered business as usual. Melchor focuses instead on telling the stories of the drug war’s soldiers, victims, and witnesses, in vignettes that capture life as it happened. There’s an out-of-work dad who takes a job with Los Zetas, breaking down bricks of coke for distribution; a woman who develops severe anxiety after a shoot-out between the narcos and the federales in front of her house; a club full of people who helplessly watch as narcos beat a man nearly to death in the street.

Melchor doesn’t stay with any single account or individual for too long. These are anecdotes and brief portraits; for that reason, they can at first appear like marginalia. But Melchor has a knack for homing in on the disquieting details that cling, such as the line outside a drug tiendita that’s so long it looks like a queue for tortillas. Or the man who just wants to buy a little coke—notably refusing to say “Los Zetas” aloud, instead referring to them as “the last letter guys”—and ends up hearing a gruesome story from his dealer. Or the former addict who recalls, “The only good hit with crack is the first one. You feel like you’ve grabbed God by the ears. It’s all downhill from there.”

The best of these stories is “Veracruz With a Zee for Zeta,” which roams from person to person in very short passages, capturing fleeting moments of their encounters with the titular cartel. These range from the mundane to the fatal: In one, a man catches wind of some shady behavior at the beach and leaves before whatever is going to happen happens; in another, a woman is killed by a stray bullet. The most unnerving of these might be the account of two wholesale workers confronted by narcos running a credit card scam. One of the narcos says that if they don’t accept his card, both the cashier and their supervisor will be found dead in the parking lot. The overarching message of these stories is terrible and plain: In Veracruz, death can find you even if you want nothing to do with the cartels.

Melchor originally wanted to write Hurricane Season as a nonfiction novel à la Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. She ultimately decided against it, reasoning that it would be too dangerous to conduct interviews where the story’s real-life murder had occurred, a known narco hideout. (Five years ago, The Nation called Veracruz one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist.) The last two essays in This Is Not Miami give an idea of what her Capote-tinged work might have looked like: Melchor takes similar liberties with perspective, adopting the first- and second-person points of view. “Life’s Not Worth a Thing” shares her novels’ breathless sentences and colloquialisms, all but absent from the rest of the collection. Following the more “objective” voice of the pieces that come before it, the switch is somewhat jarring; it has the uncanny effect of someone doing an impression. Melchor says she chose the relato and crónica styles because they’re the “most honest way possible” to give these accounts. Even though the latter may at times encourage her to overstep, it still fits with her conviction of how best to tell these stories—as she puts it, “closer to the individual experience than to the news report.” She not only encapsulates in her writing her sources’ voices but also gets so close that she can describe the shape of their eyes, the color of their mustache. “Tell me all about it,” she says to a man on the verge of launching into a tale, and he does.

Laura AdamczykLaura Adamczyk is the author of the short story collection Hardly Children and the novel Island City, both from FSG Originals. She lives in Chicago.