The Harrowing Ardor of Heather Lewis

Her fiction was miscast as merely transgressive. Rather, her novels were interested in understanding life in its most unvarnished and unmediated.

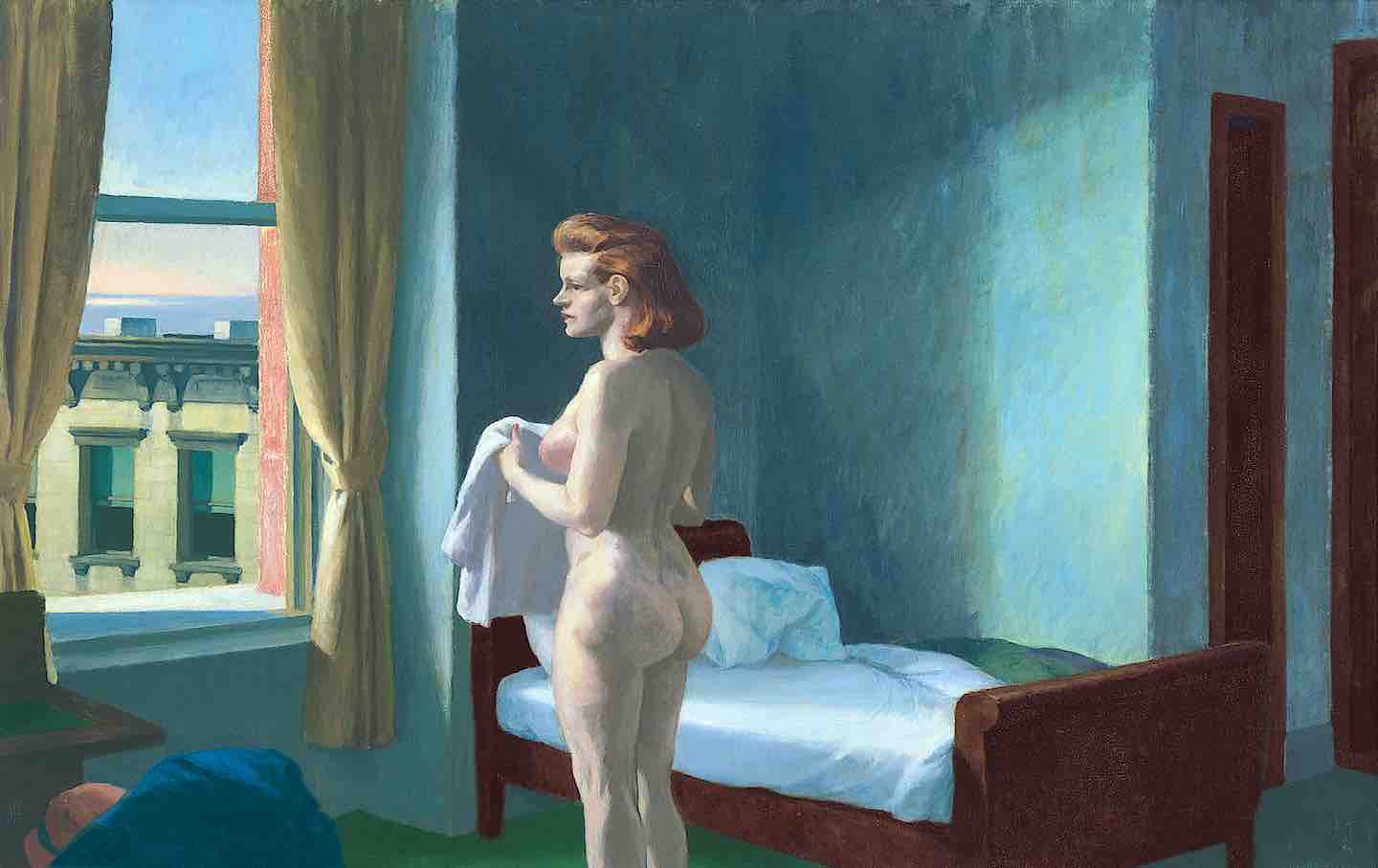

Heather Lewis is lying on a bed with her shoes off and her hands behind her head. The bed is without a blanket or cover, just two pillows on which Lewis rests her head. Her socks are dirty, her shirt tucked into her belted jeans. The walls are bare; light pours in from what appears to be the only window. The place is empty—resembling something between a motel room and a jail cell. Lewis looks at the camera, eyebrows raised, a casual ease in her demeanor coupled with an ambivalence that carries with it a tinge of discomfort. The scene is captured in a photograph by Jill Krementz, whose pictures often documented writers at work. Her 1996 image of Lewis manages to represent something true about the author’s writing: The room is austere like Lewis’s prose, and her gaze, challenging the camera’s prying look, hides nothing.

Books in review

Notice

Buy this bookThis was the year that Lewis’s second novel, Notice, was rejected by 18 publishers. The reasons were often that the story, about a teenage prostitute who goes by the assumed name of Nina and the people she becomes involved with, was too disturbing, too shocking, too bleak. The novel is narrated by this nameless girl, who, after moving back in with her parents in the suburbs, stumbles into sex work and meets an unnamed sadist and his wife, Ingrid. Both she and Ingrid are subjected to violent sex acts at the hands of the husband. The couple are especially interested in using Nina to re-create the rape and murder of their daughter. She eventually becomes infatuated with Ingrid, with whom she wants to run away. After Nina does escape the couple, returns to the parking lot where she initially met the husband, and resumes plying her trade, he has her arrested and institutionalized. Nina then falls into a sexual relationship with the woman treating her, named Beth.

Perhaps more so than the subject matter, publishers were put off by the narrator’s voice, which reads as eerily flat, describing scenes of sexual violence with incredible precision and usually without discernible emotional affect. Throughout the novel, there are hardly any recognizable decisions made by Nina; rather she engages in a random series of dissociative movements from one situation to the next, each one more precarious and dangerous than the last. All along, there’s a sense of her doing things impulsively, finding herself acting on something and not knowing why.

Another quality that likely made the novel hard to stomach for mainstream publishers is the fact that it lacked any narrative of revenge or redemption on the part of its abused narrator. There was no justice or forgiveness, no investigation of trauma or of a lurid past that might explain the behavior of the victim or the perpetrator. In fact, the roles of victim and perpetrator are at times completely obscured or blurred, the characters slipping between participation and subjugation. Lewis’s protagonist resists the archetype of the young girl; she’s neither a vengeful victim nor a waifish innocent corrupted by the world. In the book’s opening, she writes of why she started turning tricks:

This wasn’t something I was looking to do, though by how easy it happened you would’ve said it was. People have. Still, for me it happened by accident. And while it’s true I needed the money that’s not all I needed from it…. What the extra need is, the thing besides money? I’ve never pinned it down. I know it’s there, though.

It’s this existential question that opens Notice and drives its character, but it is coupled with Nina’s painfully conscious observations of every gesture that happens around her or to her or in her body. The novel is at moments harrowing, at moments absurd to the point of black humor, and in the end unbelievably moving.

Lewis never lived to see the publication of Notice—she died by suicide in 2002 at the age of 40, two years before it was published by Serpent’s Tail. It was republished this year by Semiotext(e), one of the publishers who had initially passed on the manuscript.

In 1994, Lewis had some success with her first novel, House Rules, which follows Lee, a young woman who, after being expelled from boarding school, works as a rider on a horse-show circuit to avoid returning to an abusive home. She becomes involved with an older woman and an incestuous pair of siblings who drug both the horses and the riders. House Rules and Notice share the same distinct style of narration—one of curious detachment amid a world of intense, violent feeling.

House Rules was well received, although some critics were disturbed by what they saw as the narrator’s emotional void. A reviewer for The New York Times wrote that the book’s central character was “so determinedly blank that there seems little about her to work with, and less to care about.” House Rules was included in Katie Roiphe’s 1994 essay for Harper’s Magazine, “Making the Incest Scene,” in which she argued that Lewis and a number of her contemporaries, such as Mary Gaitskill, Dorothy Allison, and Donna Tartt, relied on incest in their work as a cheap literary device to convey the power dynamics between men and women—and further, that the prurient theme had become a fad that publishers capitalized on to sell books. Roiphe’s perspective assumes that these writers were seeking to shock, relying on the subject of female suffering to gain readers rather than merely writing about something that may be painful and shocking but, nonetheless, true.

Though Roiphe’s argument is nearly 30 years old, it speaks to a persistent tendency that critics and readers have toward such taboo subjects. There’s a feeling that books with a protagonist who is a victim of her circumstances are the only ones worth publishing or reading, because they are told in a way that makes the ordeal heroic, assuring the reader that by the story’s end, all will be resolved. Lewis rejects this—refusing to give in to a kind of moralizing or preaching about the experience of being a lesbian, being a woman, or being abused. What she’s after instead is a literature of transgression, one that imagines what is possible outside the acceptable ways of talking about violence in such moralizing terms. In its detachment, Lewis’s voice achieves the effect of dissociation—describing scenes in simple, plain language, pushing the reader to be confronted with the description of violence without sensation. (Lewis was not alone in this transgressive tradition either; her forebears go as far back as Sade and Bataille, or any writer who flouted taboos to understand what effect their society’s censoriousness had on the public and private imagination.)

Lewis was born in 1961, to a wealthy couple in Westchester County, New York. Her father was the CEO of Reader’s Digest and a confidant of Richard Nixon. Lewis writes most clearly about her own childhood in a piece collected in A Woman Like That: Lesbian and Bisexual Writers Tell Their Coming Out Stories called “Richard Nixon and Me,” from 1999. The essay tracks her relationship with her father, her adolescence, and her coming out as a lesbian as it runs parallel to Nixon’s impeachment. She writes, “If he hadn’t been caught, I wouldn’t have either. Though ‘caught,’ while it might be the right word for him, wasn’t really the right word for what happened to me. Noticed was more like it.” She discloses in the essay that when she was a preteen, her father began sexually abusing her, which compelled her in her teenage years to spend little time at home, hoping to find liberation in drinking and other forms of experimentation. But her father became overbearing as she drifted and had her sent to mental institutions, shrinks, and schools for troubled youth. After she was kicked out of one boarding school, she went to Florida to work as a competitive horse jumper. She managed to get to Sarah Lawrence, where she studied with the novelist Allan Gurganus, who mentored her as she began her first novel.

After failing to find a publisher for Notice, Lewis began circulating another work, Second Suspect, a similar novel but written in the third person and concerning a New York detective investigating the murder of a prostitute by a wealthy, powerful couple. The intensity and urgency of the first-person voice that’s so powerful in Notice is diverted, and a plot-driven crime narrative imposed. “NYPD Noir” is how the novel is characterized on the back cover. With the publication of Second Suspect in 1998, Lewis found herself with an unexpected readership of noir and thriller fans. The book was even optioned by Alan J. Pakula, and Lewis was set to meet with the director in the Hamptons in the fall of that year. On Pakula’s way to the meeting, an improperly secured steel beam slid off the truck behind him, smashing through his back windshield and killing him. In the last year of her life, Lewis left New York for Arizona, where she began breaking down and using drugs heavily; she also started believing that corporate powers and the US government were conspiring against her. She returned to New York in 2002, where she ended her life at 40.

As with any posthumous publication, especially one tinged with tragedy, there is a temptation to mythologize (a number of critics have written about the belt of the brown silk robe Lewis used to hang herself). There’s a desire to search for meaning in such a tragedy, to ascribe to it a cultural significance, when perhaps it’s just as arbitrary as the steel beam falling off the truck and through a windshield.

Lewis existed in a precarious position between two worlds: the literary establishment and Manhattan’s downtown scene. Ann Rower, who was Lewis’s girlfriend from 1996 until the end of her life, wrote of how Lewis walked the line between “the cool downtown world and its community of writers, which she was too late for, and the uptown six- or seven-figure advances of the mainstream publishing world where she never really fit either.” She was a member of the New Narrative movement and the Blank Generation, a peer of Gary Indiana, Dennis Cooper, Eileen Myles, and Dale Peck, who defined this post-AIDS milieu as a time “when literature was, as it so rarely is, relevant to more than students of literature.” The style Peck thought his generation shared was one of directness—a desire to use writing to capture the experience of living in a form that might feel unmediated, unvarnished.

Indiana wrote of this milieu in his 2001 novel Do Everything in the Dark. Lewis and Rower are thinly veiled characters in that work— Caroline and Denise are both writers who move to New Mexico, where Caroline (the Lewis character) begins to lose her mind and relapse into drug addiction. Indiana writes of her:

The sales of that first book did not reach the astronomical figure Caroline anticipated. Women with less talent but a firmer grasp of the melodramatic, self-pitying note consumers of the material Caroline was dealing with expected such a book to strike, women who spoke the language of “hurt” and “betrayal” and “the need for closure” had also been raped by their fathers, and wrote books about it that did not engage, as Caroline’s did, any irreverent sense of absurdity about the concept of “family” itself, or indicate any extraneous brain activity. Caroline had not adequately depicted herself as a victim hollowed of all substance by violation. She was the least lucrative kind of victim: an intellectual who did not need rescuing by a strong yet gentle man’s “healing love,” a lesbian who read Kierkegaard, pondered over string theory, and worst of all, did not think forgiveness brought a nice warm feeling in its wake.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Indiana seems to address the position that Lewis occupied as an outlier among her literary peers. What she had created in her work was something far more complex than just the fallout of a traumatized person. Rather than pointing out the abuse or incest or violence, Lewis goes into it—into its murky territory, the conflation of pain and pleasure and, ultimately, an ambivalence about the point of life itself.

This elusive, desperate desire that drives her narrator seems to me the central subject of Notice. It’s what gets Nina both into trouble and out of it; it’s the thing that keeps her alive but also pushes her to the brink. It is likely this same sort of desire—an urgent attempt to make meaning of her survival—that drove Lewis to write.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Best Albums of 2025 The Best Albums of 2025

From Mavis Staples to the Kronos Quartet—these are our music critic’s favorite works from this year.

Forrest Gander’s Desert Phenomenology Forrest Gander’s Desert Phenomenology

His poems bridge the gap between nature’s wild expanse and the private space of one’s imagination.

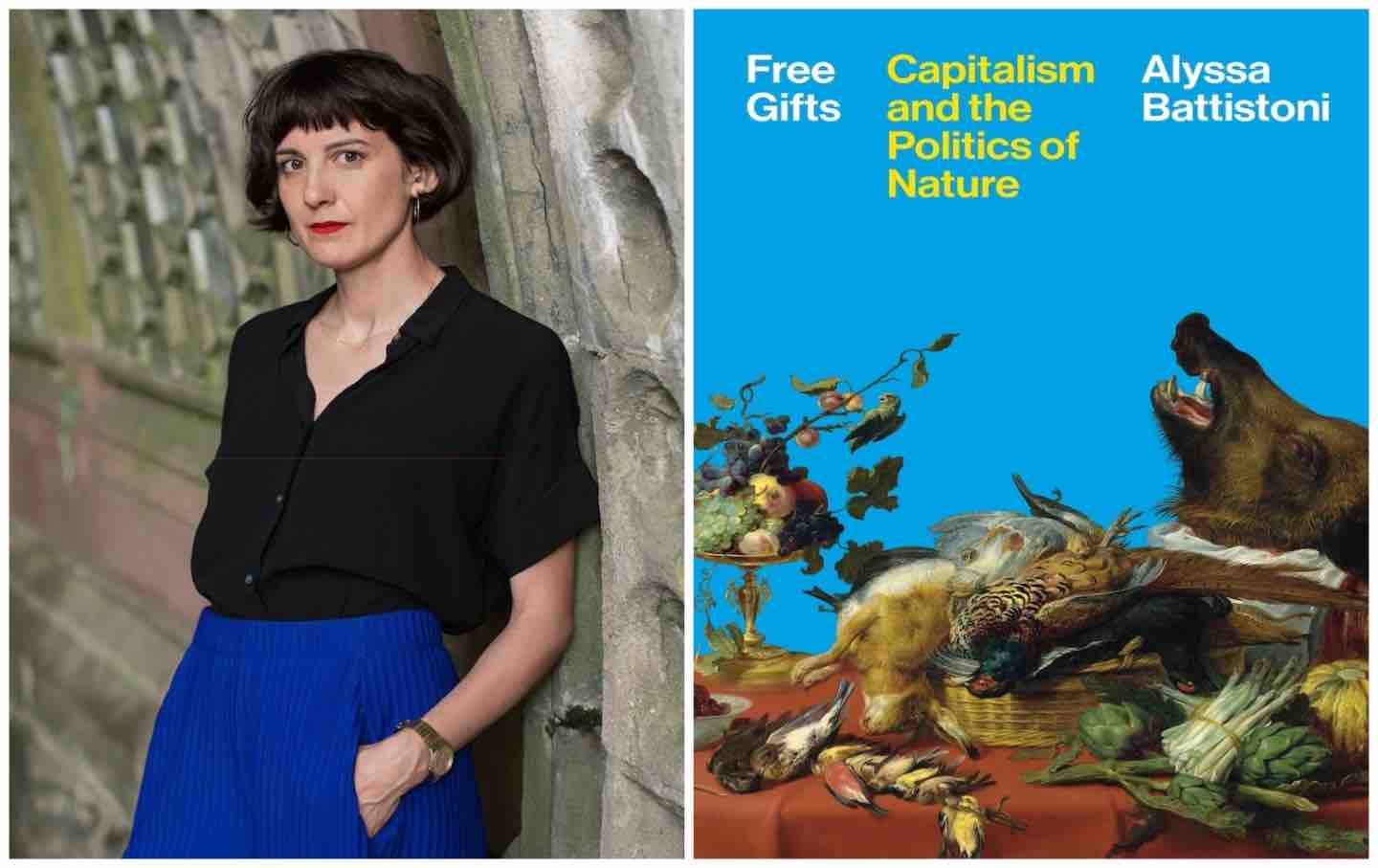

Capitalism’s Toxic Nature Capitalism’s Toxic Nature

A conversation with Alyssa Battistoni about the essential and contradictory nature of capitalism to the environment and her new book Free Gifts: Capitalism and the Politics of Nat...

Solvej Balle and the Tyranny of Time Solvej Balle and the Tyranny of Time

The Danish novelist’s septology, On the Calculation of Volume, asks what fiction can explore when you remove one of its key characteristics—the idea of time itself.

Muriel Spark’s Magnetic Pull Muriel Spark’s Magnetic Pull

What made the Scottish novelist’s antic novels so appealing?

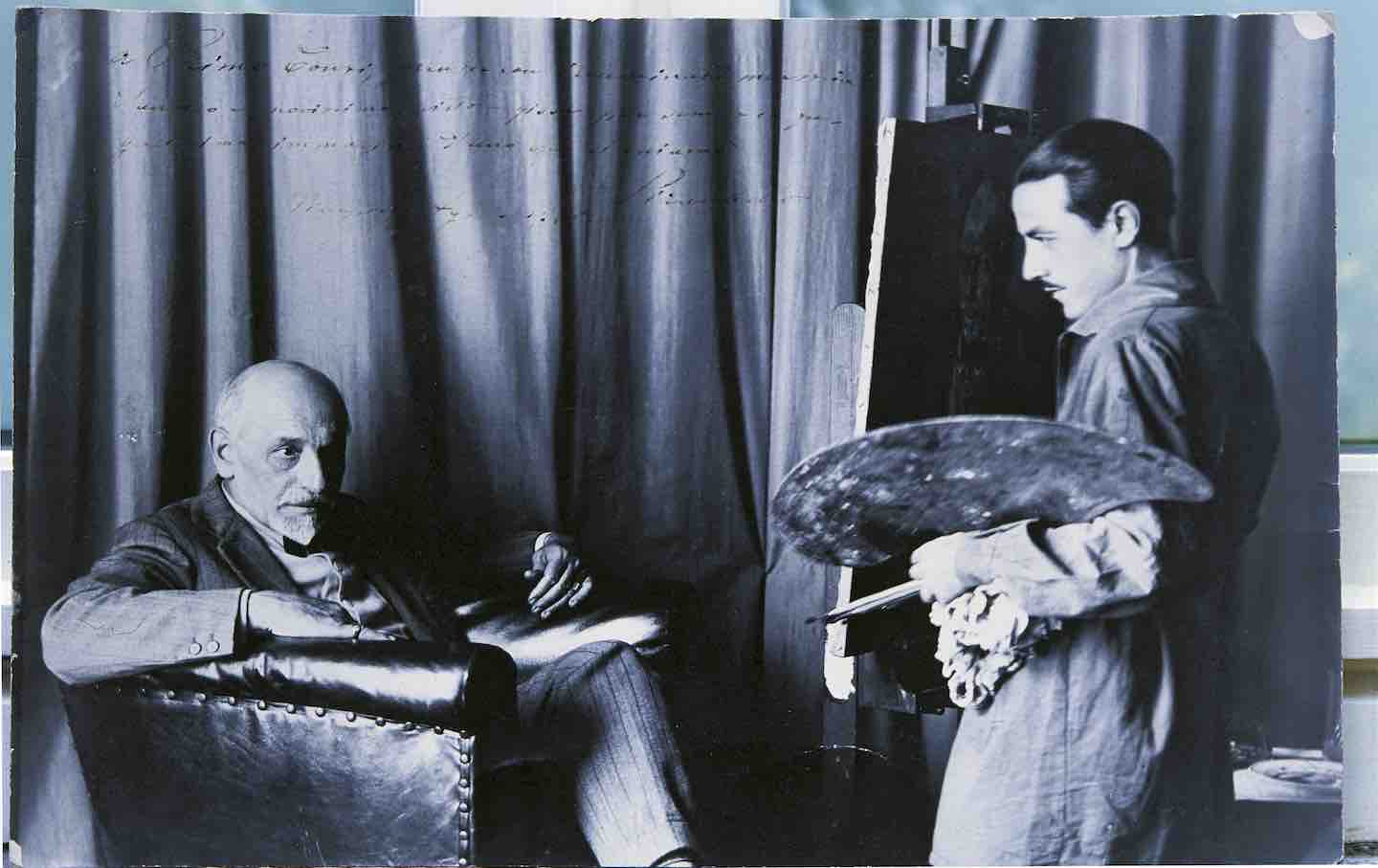

Luigi Pirandello’s Broken Men Luigi Pirandello’s Broken Men

The Nobel Prize-winning writer was once seen as Italy’s great man of letters. Why was he forgotten?