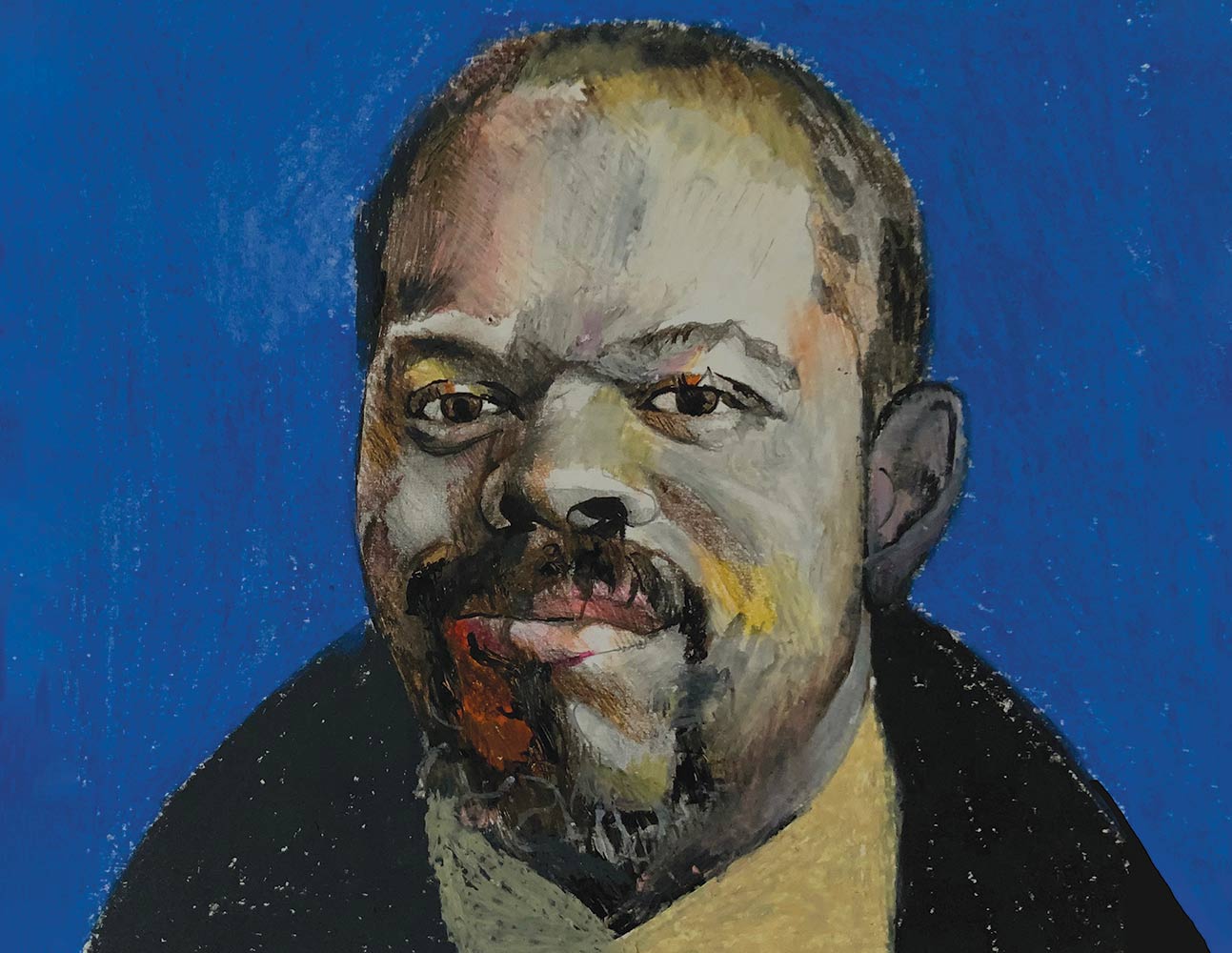

Illustration by Andrea Ventura.

If extraterrestrials were to read American poetry, would they be able to deduce from it that society existed? I suspect they wouldn’t. Not unlike autofiction, the typical lyric poem transcribes the consciousness of a sensitive observer taking in a world in which they don’t exactly belong. This onlooker is often a narcissist who writes with a mirror and a microscope. Their writing is overstuffed with the self: the poet as mopey observer, the poet as damaged comedian, the poet as traumatized humble-braggart.But this abundance of self-regard leaves little room for other people. If other humans stepped into the poem, they’d overpopulate its one-person biosphere of verse, and those who do pop up—say a lover, a mother, someone deceased—usually hover in misty form, a Jedi force ghost.

While it would be unfair to expect poetry to assume the ambitions of the social novel, there’s often been something sketchy about poetry’s inclinations toward the individual and interiority. The reading experience can be like watching an ontological CSI episode where the poet has clicked “enhance” too many times, zooming in so minutely on the self that all human society ends up outside the frame. Such self-centeredness may explain poetry’s ascendance during the past decade as self-help and branding for the puffed-up denizens of Twitter and Instagram.

The lyric seems so bound up with the individual that it’s hard to imagine what a social poetry might look like. One possible direction forward is suggested by John Keene’s new poetry collection, Punks. A languorous and nervy book, Punks tells a social history of desire, at once surreptitious and brazen. Signaling the return of the social, its poems emanate a radiant kindness. Its miracles come not so much from a glistening metaphor or the projection of self; Keene avoids such luminous tricks for an endeavor that might seem modest but is actually far larger in scope. He can actually see other people.

If many poets write from a metaphysical nowhere, Keene’s poems depict a glittering demimonde that is by turns Black and queer. Written in the first person but never confessional, Punks forsakes the lyric in favor of a glorious psycho-geography of gay bars. These are deft sketches of a world hidden away from the street but more expansive than solitude and friendship, the semiprivate fields of eros: cruising in the fens; the queer bookstore A Different Light; gay bars like the Leland in San Francisco and the Napoleon, Sporters, Bohemian, and the Zone in Boston; and, in the title poem, the Asian/Nuyorican counterculture of a Loisaida and Chinatown now long vanished. The social dynamics of these queer spaces provide what a novelist might call motivation: To use the jargon of literary craft, who will the narrator hook up with tonight? Such romantic pursuits, the entire focus in a more conventional account, appear in Punks as simply one facet of a fully elaborated social setting. The poems glamorize the adventure of milieu, a libidinous zone where the line between lover and stranger, friend and acquaintance, constantly flickers. What emerges is the thrill of the background, the complex heterogeneity of the ways we relate to each other. This makes Punks vibrate with a startling sense of sanity. It is the rare poetry book in which the speaker and the beloved always exist within a fully observed world, whose inhabitants glow with a humanity larger than our own glorious sadness.

We’re used to poets presenting themselves as frail prophets of their own neurasthenia; their self is a barricaded city that houses only despair and triumph. Punks breaks down the self’s walls and smuggles in an ensemble cast of others—strangers, observers, acquaintances, friends, rivals, frenemies, hook-ups, lovers, soul mates, scenesters, and fellow hucksters of the libido. Keene can somehow weave the more delicate filaments of social life into something rich and complex. Rather than summon up an “authentic” self, his poems play the score for a cinema of the encounter.

Beers later, I turned to my most recent seduction and caressed his massive mahogany forearm. I was leaving, I told him, expecting him to follow. Instead, he pointed to a tall brother twice my age crooning something into the neck of the bartender. He kissed me and promised he’d call tomorrow. Outside, twilight, like a needle on a new song, was descending.

There are no supporting characters in Punks, just as there are none in life. Everyone is a protagonist, and maybe you were simply performing a walk-on in someone else’s story. Here the speaker feels a mix of arousal, envy, flirtation, insecurity, mild disappointment, people-watching, gossip, loving hatred and loving betrayal, a belonging that has been just achieved and just thwarted. Most poets prefer heroic emotions, like wonder and despair, but most of us live our days in these minor keys. Keene’s lack of self-absorption paradoxically allows him to write the self with a greater amplitude, a persona grown large and voluminous with the miscellaneous effects brought by social life.

A Keene poem is a democracy of others. That generosity of scope imbues his poems with a sense of equanimity, a state rarely depicted in contemporary poetry. The self is never static, is always in transit, and cannot exist decontextualized from its relationships. In a poem called “The Haymarket,” he pans away from the melodramas of his own heartbreak toward love’s broader constellations. The speaker gradually vanishes as he remembers “the night you tore / out my throat over my words with an ex, whom you’d hurled / from your car years before when you first encountered / his tales of woe, whom later I observed sneak / out of Keller’s to avoid a Brooklyn ass-whupping.” When we get to the following sentence, the scope of the narrative dilates even wider. The poem flies past the present lover and the last one too and recounts when “two drag queens / tall as Masai threw down in front of the Dumpsters, / hurling pumps and wigs like gladiators.” The queens quickly attract a crowd of onlookers, presumably friends and possible lovers: Warren giving background “knowing the full tea,” Johnny presenting “beauty in a snaggled grin,” and Darrell, who will later move in with the narrator’s lover—in other words, an entire ensemble cast compressed into half a sentence, a 10-line panorama.

Keene often curtails his own “voice” so he can best document this complex external world. If he over-relied on metaphor, such figuration would taint his chronicle with subjectivity. You wouldn’t be able to see the other people, and because our relationships with them define who we are, the self would also become occluded. And so many of Keene’s creative experiments happen invisibly at the level of sentence structure. Syntax becomes an architecture. Keene’s a paratactical poet, crafty with modifiers, and wields the whole scope of grammar where other poets would rely on analogy. The cantilevers of his sentences support loads beyond the protagonist and end up bearing the weight of complex interactions. Some of his sentences flash by like the parenthetical whispers of Lyn Hejinian’s fractured autobiography, My Life. Others expand into labyrinthine hallways of discourse, and by calibrating back and forth, Keene can go from zero to Jamesian in just a few commas. In his first book, Annotations (1995), Keene’s constructions suggested an Augustan delight in ornament, economy, and tense, a style one could call syntactical dandyism, but in Punks he unfurls grammar in subtler, looser ways, opening the sentence to let in the quiet extravagance of all those he loves and remembers. In “Elegy: Boston,” the speaker wanders over Harvard Bridge, despondent over a failed relationship, and concludes, “That night I stalled, not wanting to reach Boylston, buy books and wine and candy and circle like a gull above feeling. I stood there, as I sit here now, watching the red-brick beacons beckoning dimming, like all desires, and loss itself, to mere horizons.” The speaker’s heartbreak is mediated by dependent clauses, whose distancing mediations he fights. He wants to be present. Nevertheless, this heartbreak will one day become just another memory recollected by a future self and fade to “mere horizon,” not anguish, just someone’s own private sublime glowing like a star.

The magic warmth of Keene’s poems may reflect the tendency for queer spaces to express more egalitarian forms of love. Still, every community is partial: “I knew / I’d never see my crew here,” he notes of one bar. When he writes about Chicago’s gay enclave, Boystown, he recognizes that these Lakeview streets are “alive with solidarity” but can’t help but feel there is “little room for blackness as I live it, / not exotic, a mere mirror, but the center.” The poem, which alludes to a line from Mos Def, transforms into an ars poetica, a manifesto about the emancipatory potential of truly democratic communities:

So I’ve learned to thrive on silence, exile, cunning, past surviving, fashioning my own spaces, places nurturing passions I live and own and passing them on, remaining open, imagining possibilities that free us, nexuses where all my families connect, dialogue in respect, where no one mans the barricades and chords from every singer conjure our common futures from forgotten words.

I want black people to be free, to be free.

“Silence, exile, cunning”: Keene is quoting, of course, the words of another colonized writer, James Joyce, who recommended that the Irish artist leave behind the parochialism of home, family, and church and adopt the cosmopolitanism of European exile. While Keene seems to endorse this fugitive trinity, his own solution is less defensive. Rather than flee your home, you can build a new one.

When Keene was a young writer in Boston, he found one such community when he joined the Dark Room Collective, the now-legendary poetry group based in Cambridge, Mass. It was founded in 1987 after the poets Sharan Strange and Thomas Sayers Ellis drove to Harlem to attend the funeral of James Baldwin. “We felt somewhat like distant young cousins of a family patriarch whose passing we felt as momentous but could be met without the deepest sorrow for we had known him only from a distance,” Strange wrote. “Instead, our sorrow was suffused with a kind of energy, a desire to make something positive out of loss….” Out of a desire to connect with their “living literary ancestors,” as Strange put it, she, Ellis, and a third cofounder, Janice Lowe, began organizing live events, writing workshops, and reading groups in the living room of the old Victorian house in which Strange and Ellis lived.

We have a tendency to think of aesthetic movements as team-ups between famous artistic legends, as if modernism were just what happened when Eliot, Joyce, and Woolf formed the Justice League of Literature. What is striking about the Dark Room Collective is its sense of egalitarianism. There was no hierarchy of superheroes. Keene himself had been a loan-officer trainee, not a Harvard undergraduate, but he’d glimpsed Ellis’s “high-top fade around town,” heard about the collective from his barber, and was welcomed in. Its members would include the poets Major Jackson, Kevin Young, Tisa Bryant, Carl Philips, and the Pulitzer Prize winners Natasha Tretheway and Tracy K. Smith, but the group had more than 70 members and “extended family,” not all of whom were famous at the time or became famous after.

The Dark Room Collective had a seemingly transformative effect on Keene, much like its successor organization, the African American poetry residency Cave Canem, but if you weren’t there, you’d have no way of knowing how. That is what’s magical about countercultural art scenes. Experiences with other people cannot be abstracted into knowledge, though Keene did recall in a 2016 interview what made the collective so special for him. Describing a reading featuring Alice Walker, he said, “There was a young woman who had really been struggling, and she was crying, and she told Alice Walker that her work had basically kept her alive. And Alice Walker—I’d never seen this—she left the podium, and came and embraced her.” What seems remarkable about this anecdote is how Walker abolished the usual division between author and reader, speaker and spectator, through an act of love. As the late bell hooks wrote, “This is the most precious gift true love offers—the experience of knowing we always belong.”

What might such belonging mean? How can literature enact an ethics of relations—not simply show off the singularity of an exceptional auteur, but practice a literature of Black collectivity? This sense of togetherness that Keene experienced at the Dark Room Collective and Cave Canem would also form the subject matter of his writing. All crowded subtext and subverted self, Punks continues the social portraiture that began with Annotations, which documented Keene’s coming-of-age as a gay child in a Midwestern Black community. His parents, who were middle-class admirers of John Coltrane and Eldridge Cleaver, always believed they “would eventually own their own property.” The hopefulness of the statement (“would eventually”) belies the wavering impossibility of becoming landed—the dream of Black class attainment forever just beyond the horizon. What may look like family and home from the inside, Keene realizes, can be diagnosed externally as mere assets: “private property and ‘propriety’ are to the EuroAmerican bourgeois what the land and ancestors were to his other forebears, the fulcrum around which their entire sociopolitical view turned, and turns.”

Annotations is an unusual bildungsroman that, unlike today’s confessional ethnic memoirs, is written in the third person and largely avoids Keene’s own voice: “By choosing and extolling certain models to the exclusion of all others,” Keene confesses at one point, “he sought to deny the impending crisis of his own self-representation.” As the book’s title suggests, perhaps a singular voice is impossible, since we are all synthesized from our family, our geography, and our class, and so all we can do is annotate that inheritance. “Intuition provided the first step, information the second, until he realized that by combining the two he was creating a handy index of being.” Keene points to how we are all texts from a library whose contents can be both internal and subjective (intuition) and also formed by the structures created by history. Merging self and system requires a dialectical process. You must name yourself and fashion a “handy index of being.” Keene’s words recall a recommendation by Paul Gilroy, who, quoting Gramsci, encouraged us all to remember that we are the “product of the historical process to date which has deposited in you an infinity of traces, without leaving an inventory.”

In a section of Punks titled “Dark to Themselves,” Keene resurrects thinkers and artists of the Black Atlantic in adventurous persona poems. His cast of characters includes Martin de Porres, the Dominican saint who advocated for racial harmony; Denmark Vesey, the leader of a thwarted slave revolt; the gifted Baltimore farmer Benjamin Banneker, who surveyed the site of our nation’s capital; the Harlem Renaissance intellectual Alain Locke; and many jazz artists. What could be a mural of multicultural uplift feels rangy, estranged from a message, and too limber to pin down. As Charlie Parker says in one poem: “I is another.” The characters arrive surrounded by a halo of historicity, but they’re still questioning, wondering, metaphysical, always fighting out from amid a physical action, a present tense. None of them feel like they have been completed.

These poems continue an intervention in the past begun in Keene’s second book, the fiction collection Counternarratives, a playfully impersonal investigation of Black history that feels like it was cowritten by Jorge Luis Borges and Gerald Horne. An early story follows an enslaved man named Zion who experiences his first taste of punishment when his master prohibits him from singing. This moment echoes Frederick Douglass’s remark that he first realized slavery’s dehumanizing effects when he encountered enslaved people whose bondage was momentarily lightened, and he heard them sing rapturously their full joy and sadness. In Keene’s story, Zion escapes, gets captured, and flees again. He finds himself finally imprisoned and soon to be hanged. The next morning, the town discovers his cell empty. Zion has escaped again! He is the infinite fugitive who is almost manically impossible to restrain, and the erupting kernel of his agency had been his own artistic expression. The sheer force of your song can act as either revolution or an elegy that you sing for yourself as you figure out how to elude the gallows—a statement about the stakes of art that Keene also explores in Punks. In a poem called “Apostate,” we meet a furious horn player whom Keene describes as “wrestling like Jacob / the relentless angel that yearns / to slay you.” This piece ends: “Passion is a song you sing / on your own terms: the set opens, / and you hold your breath / to map the evening’s destiny: sound. / Death, get ready.” The poem does not name the musician. We know he is a dentist’s son from Alton, Ill. When we read Keene’s notes, we learn that he is a fellow native of the St. Louis area: Miles Davis, who when asked by a reporter how he wanted to be remembered, replied simply: “Sound.”

While Zion and Davis come across as swaggering artist-heroes, they are not singular. When Zion finds himself finally imprisoned, he sings a keening dirge addressed “To all fellow Brothers and Sisters of Africk,” many of whom listen tearfully outside. What the artist wages in pursuit of freedom can be a dream for everyone. In Annotations, Keene’s parents aspire toward finally having a space of their own, and the book has a throwaway line that hints at the full horizon of this dream: “The threat and the promise, Palmares”—the name of the community of escaped slaves who fended off colonizers for a century. Such maroon societies appear in Counternarratives, where soldiers casually obliterate a quilombo erected by once-bonded fugitives. This is what Keene’s books commemorate: the threat and promise of belonging, the perpetual fragility of belonging. Punks is Keene’s most intimate book, and one that chronicles the fading present. The communities are still here, found in gay bars, queer bookstores, rent parties, and other spaces that hold people together around love.

“Love your shadows and their silent censure,” Keene writes in the final poem of Punks. “Love yourself, but not too much / that you cannot love everything and everyone else.” Because love is a fraught process, a delicate interplay of power and vulnerability, these poems do not sentimentalize love; they present the challenge of it. Romance flickers in these poems, fully cunning. In “If I Don’t Call My Basque Friend,” the speaker and a Basque woman stay up dancing until the sun emerges from the river. They stroll the alleyways, heads on each other’s shoulders, talking about poetry and the future. “I assumed at one point that this might have been love, my best chance at it, this sharing so deep it warms the marrow, makes you wake each morning to check that it hasn’t vanished like the previous day.” The poem ends with the speaker preparing to “cheat” on her with another man.

There may be a reason why the words “ardor” and “arduous” share a resemblance. There is lust in this book—one paramour “writhes in bed like a loose hose when he comes”—but love is also a labor, “a dream where both of us are trying, at the same speed, without quitting.” In a poem called “In the Warm, Sunlit Room, Talking of Brotherhood,” the speaker attends a consciousness-raising meeting and interprets the gathering as a pick-up spot: “Oh nights of wanton youth, desire easier than rolling paper to light and burn through.” The meeting is also the start of something deeper. He realizes that rather than flirting or even holding forth himself, he can listen to others. Keene notes that this all takes place “years before Chuck leads me through the ‘love exercise’ and I can say ‘I love you’ to a man who is not my partner and mean it.” This clarification tells us that his past self is only a novitiate, an apprentice in the art of love, someone who understands passion and is only slowly learning a love larger than desire.

“Love is an action, a participatory emotion,” bell hooks wrote. “Whether we are engaged in a process of self-love or of loving others we must move beyond the realm of feeling to actualize love.” Love is not simply something that strikes us from the outside, like weather. We must practice love, put our egos aside and fully open ourselves to the other. One especially profound example comes in “The Angel of Desolation,” which begins when the narrator picks up a doomed stranger who “whispers his name in a Delta accent so soft I can hardly hear him…like he’s revealing an embarrassment or a secret.”

The man wears a gabardine vest, a gold pinkie ring, and chains. “He knows that I have a soft spot for men who show a little too much gold, who lack for taste but not for modesty,” Keene continues. Where is the knowledge of the poem? If you look carefully, you will notice that Keene describes it as issuing not from the poet but from the beloved, who comes possessing his own discernment. Rather than basking in his own song, Keene is himself observed, and he looks back, caressing the beloved with his looking. “There is something terrible I’m sure he wants to tell me,” he writes, “but I don’t press him, and being courteous he holds back for now.” There is a delicacy of perception here, a fineness of observation that acts like an expression of gratitude. In a more typical love poem, the poet would perform a masterful characterization of the beloved, as if describing a painting or sculpture. Keene takes a different tack—that of discretion. The speaker detects a wound in the beloved, a shame that desperately needs to be spoken. The beloved is perceived so carefully that he seems utterly accepted, free to be vulnerable, but precisely because he is so fully realized, he is too large to be apprehended in just a few lines. You cannot learn all his secrets yet. You’ve got to get to know him first.

These days, it seems like the highest praise a poem can get is someone tweeting in all caps, “This destroyed me!” I have often wondered why someone would want to be destroyed. Rather than immolating the reader, Keene’s poems keep opening up, rippling dynamically outward, playing back and forth between self and other, scene and setting, softly encouraging you in each line to be more generous with your intimacy. What is most startling about reading Punks is that, perceiving the world through Keene’s eyes, you begin imperceptibly relaxing your own spiritual narrowness and start to notice yourself doing the unthinkable. You start loving others beyond the usual perimeter of your affection. Like politics and friendship, love is a collaboration, and the holy joy of this book is how Keene and his paramour move like “two ballers / shadowing each other’s moves / this freestyle of loving, our groove.”

Ken ChenKen Chen is the author of the poetry collection Juvenilia and is at work on a new book tentatively titled Death Star.