Devastating Empathy: Jules Feiffer, 1929–2025

The cartoonist and writer proved that the deadliest skewering is informed by understanding.

After watching Gore Vidal’s play An Evening with Richard Nixon (1972) Jules Feiffer unexpectedly found himself “feeling sorry for Nixon…. Just because of the overkill and the setting up of false terms.” Feiffer is a trustworthy guide through the thickets of political art. From 1956 to 1997 in his famous weekly strip in The Village Voice, Feiffer was America’s premier satirical cartoonist, the artist who best captured the tone and timbre of American public rhetoric and private anxiety from the time of Dwight Eisenhower to Bill Clinton. The key to Feiffer’s art was that he avoided the very trap Vidal fell into: Feiffer could be savage in skewering political and cultural folly, but he avoided heavy-handedness by leavening his satire with empathy.

Feiffer, who died on January 17 at age 95, wrote and cartooned for many other publications, including The Nation. Although his Village Voice cartoons were perhaps his greatest legacy, he was in truth a man of many talents. Feiffer started his career right after World War II as a teenage assistant and eventual ghost for pioneering comic book creator Will Eisner, whose stories of the Spirit brought a worldly, noir atmosphere to the superhero genre then dominated by crude slambang action. After his apprenticeship for Eisner, Feiffer first made a name for himself at the Village Voice, but quickly branched into myriad other fields ranging from animation (the Oscar-winning Munro, directed by Gene Deitch in 1961), playwriting (Little Murders, 1967 and subsequently a movie in 1971, directed by Alan Arkin), screenwriting (notably Carnal Knowledge, directed by Mike Nichols in 1971, and Popeye, directed by Robert Altman in 1980), novels (Harry: The Rat With Women, 1963), children’s books (The Man in the Ceiling, 1993), memoirs, and many other genres and forms.

The throughline that held together this prodigious body of work was his acuteness as a psychologist. Especially when one looks back on Feiffer’s long and distinguished career as a political cartoonist, what is striking is how he was most bitingly accurate when he allowed a measure of empathy into his work. He often balanced political contempt with human sympathy.

Having spent so much time in theatre, Feiffer seems to have picked up by osmosis the actor’s gift of impersonation—the ability to look at the world through the eyes of even the most unsympathetic soul. Now that we have tapes and memoirs that give us the private conversations of Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon, it is uncanny how often their small talk could have been scripted by Feiffer. In a Vietnam war era strip, Feiffer translated Lydon Johnson’s political fate into a melodramatic western. A cute little missy is asking her “big daddy” what happened to Great Society, the plans for domestic betterment that were derailed by the Vietnam War. Like a father comforting his daughter after a beloved horse has died, Johnson offers the young girl a soothing oration. “Great Society has gone away, has gone t’sleep, has gone to a better land’n yew an’ I know of child,” the President says.

In 1976 the historian Doris Kearns Goodwin published Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream, based on her extensive interviews with the late president. Like his comic strip counterpart, Goodwin’s LBJ saw himself as the hero of a cowboy movie, with his efforts to build a good life for the womenfolk at the homestead destroyed by the need to go out and fight enemies. “I knew from the start if I left a woman I really loved—the Great Society—in order to fight that bitch of a war [in Vietnam] … then I would lose everything at home,” Johnson told Goodwin in 1971. LBJ’s actual internal monologue, it turns out, was only a shade hokier than the one Feiffer imagined. Feiffer’s strips were as much about psychology as politics.

Like his contemporary Charles Schulz, Feiffer brought an awareness of therapeutic culture into the comics. Therapy-inflected humor was very much part of the postwar ambience, found in the many “sick” comedians whom Feiffer also had an affinity for (and sometimes collaborated with): the team of Mike Nichols and Elaine May, Lenny Bruce, and Shelley Berman. These comedians, like Feiffer himself, eschewed the gag format of the vaudeville tradition for a more urbane, inward looking, language-based humor: a comedy often rooted in noticing how therapy-talk about relationships and neuroses was remaking everyday speech.

It’s no accident that Feiffer’s art has the jangly looseness of a Rorschach test or a psychiatrist’s notepad. Like a good analyst, Feiffer allowed his characters to free-associate their way to self-discovery. His focus repeatedly returned on the lies people tell themselves, the rhetorical self-deceptions that allow powerful leaders (and their followers) to do bad things. The characteristic Feiffer strip is a monologue where someone comforts themselves in the false security of their own rhetoric but then reveals a sharp contradiction at the end.

This unrelenting tug of war between necessary illusions and cynical self-awareness marks the lives of Feiffer’s recurring character, notably the nebbish Bernard Mergendeiler who prides himself on being a nice guy even as he seethes with anger toward women, and the nameless dancer whose lithe capering across the printed page constantly enacts the story of hope springing back to life after defeat. In one early strip, Mergendeiler reflects on the fact that he often doesn’t believe what he’s saying—or really trust anything he hears from others—so that for him life is really about finding the most comforting deception. “That is what I have finally come to believe,” he says. “My lie, right or wrong.”

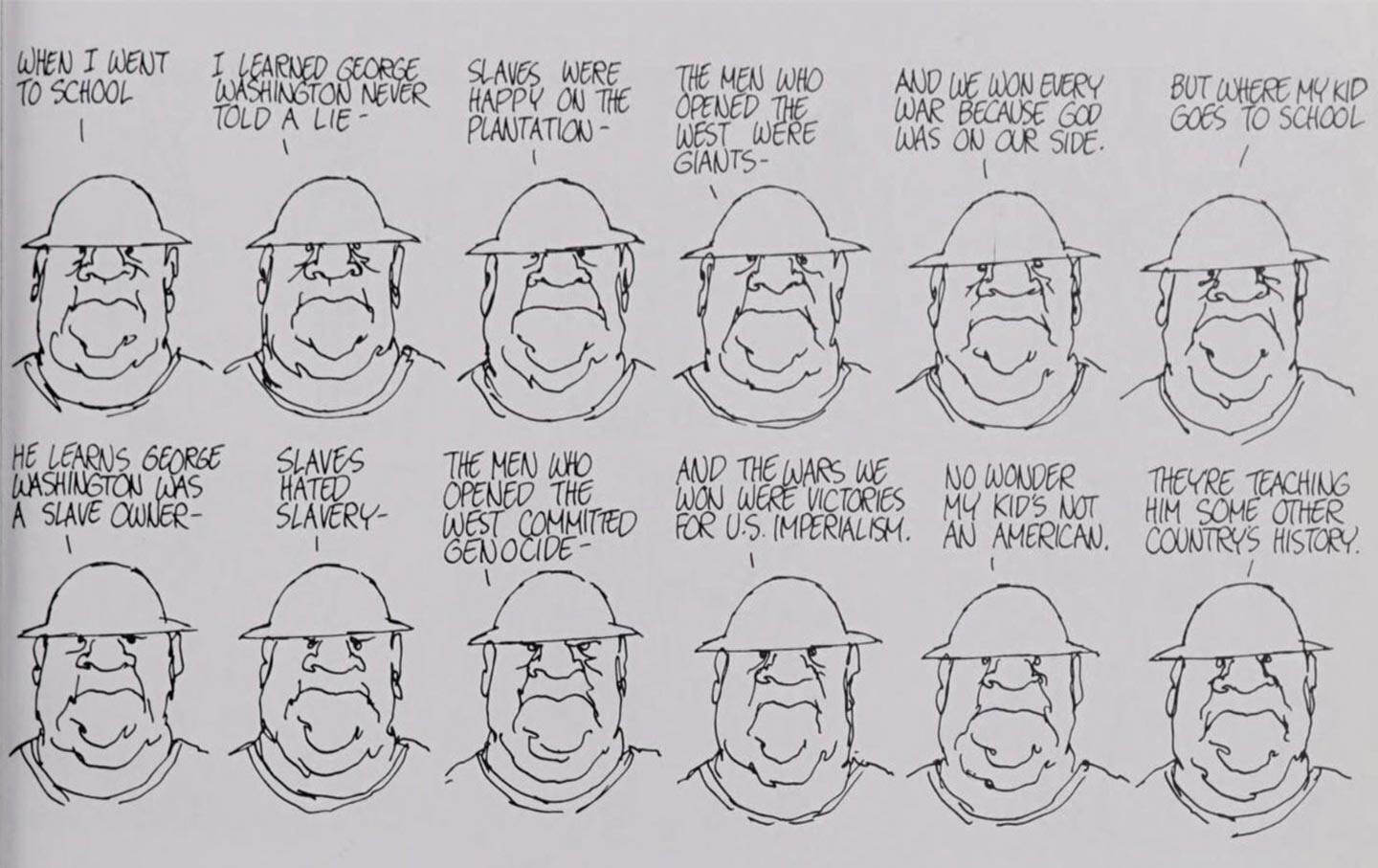

A 1960s strip shows a white construction worker reflecting on the generation gap. “when i went to school,” he muses. “i learned george washington never told a lie—slaves were happy on the plantation—the men who opened the west were giants—and we won every war because god was on our side. when my kids goes to school he learns george washington was a slave owner—slaves hated slavery—the men who opened the west committed genocide—and the wars we won were victories for u.s. imperialism. no wonder my kid’s not an american. they’re teaching him some other country’s history.”

What makes this strip so incisive is that it not only lays out a real divide but does so in the voice of a main character—whose opinion Feiffer doesn’t share. It’s perfectly plausible for someone to be aware of the darker narrative of American history while still preferring the more comforting mythology of nationalism. Indeed, that’s how motivated reasoning often works.

A 1980s strip features a young Jewish man expertly laying out the sophistry he hears form his elders on Israel/Palestine

“Uncle Max says when Arabs kill Jews, the world forgives. When Jews kill Arabs, the world is outraged. Uncle Jake says it’s a moral disgrace that more is made in the media over Israel in Lebanon than the Russians in Poland or Afghanistan.” The young man lists off other transparent efforts at deflection, takes note of the health complaints in his family and wryly concludes, “hypocrisy is not good for the jews.” Like so much of Feiffer’s work, the strip has lost none of its bite and relevance.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Self-deception and motivated reasoning lead to ugly behavior. Carnal Knowledge, with Jack Nicholson and Art Garfunkel vividly bringing to life the folie à deux of a pair of woman-haters, is an abrasive movie. It can be a tough watch. The film occupies the ambiguous borderland between misogyny as a subject and misogyny as an expressive mode. This is territory also explored in the contemporaneous work of many male writers of that time such as John Updike, Philp Roth, and Saul Bellow. How one interprets Carnal Knowledge depends on whether you see it as providing a description or a permission. I first saw the movie in the early 1980s when it ran unedited on a local television station known for its daring programming choices. I found the main characters repulsive, but a lot of my male classmates were echoing the Jack Nicholson character as if he were a role model, constantly referring to various girls as “ball-busters.”

Empathy, then, can be tricky, especially if the audience doesn’t catch the irony or satire. But this danger itself speaks to the power of Feiffer’s psychological portraiture: a misogynist can look at the characters in Carnal Knowledge and recognize a true reflection.

Feiffer’s devasting irony informed his vast body of work. The full scale of his achievement has yet to be measured.

Note: Parts of this essay originally appeared in 2004 in Indy Magazine.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from

Jeet Heer

The Shocking Confessions of Susie Wiles The Shocking Confessions of Susie Wiles

Trump’s chief of staff admits he’s lying about Venezuela—and a lot of other things.

Why Epstein’s Links to the CIA Are So Important Why Epstein’s Links to the CIA Are So Important

We won’t know the full truth about his crimes until the extent of his ties to US intelligence are clear.

In America, Mass Shooting Survivors Can Never Know Peace In America, Mass Shooting Survivors Can Never Know Peace

A growing number of US residents have lived through more than one massacre.

Corporate Democrats Are Foolishly Surrendering the AI Fight Corporate Democrats Are Foolishly Surrendering the AI Fight

Voters want the party to get tough on the industry. But Democratic leaders are following the money instead.

Sleepy Donald Snoozes, America Loses Sleepy Donald Snoozes, America Loses

It’s bedtime for Bozo—and you're paying the price.

The Revolt of the Republican Women The Revolt of the Republican Women

Speaker Mike Johnson’s sexism is fueling an unexpected uprising within the GOP caucus.