How White-Collar Criminals Plundered a Brooklyn Neighborhood

Stacy Horn’s Killing Fields documents how East New York was ransacked by the real estate industry and abandoned by the city in the process.

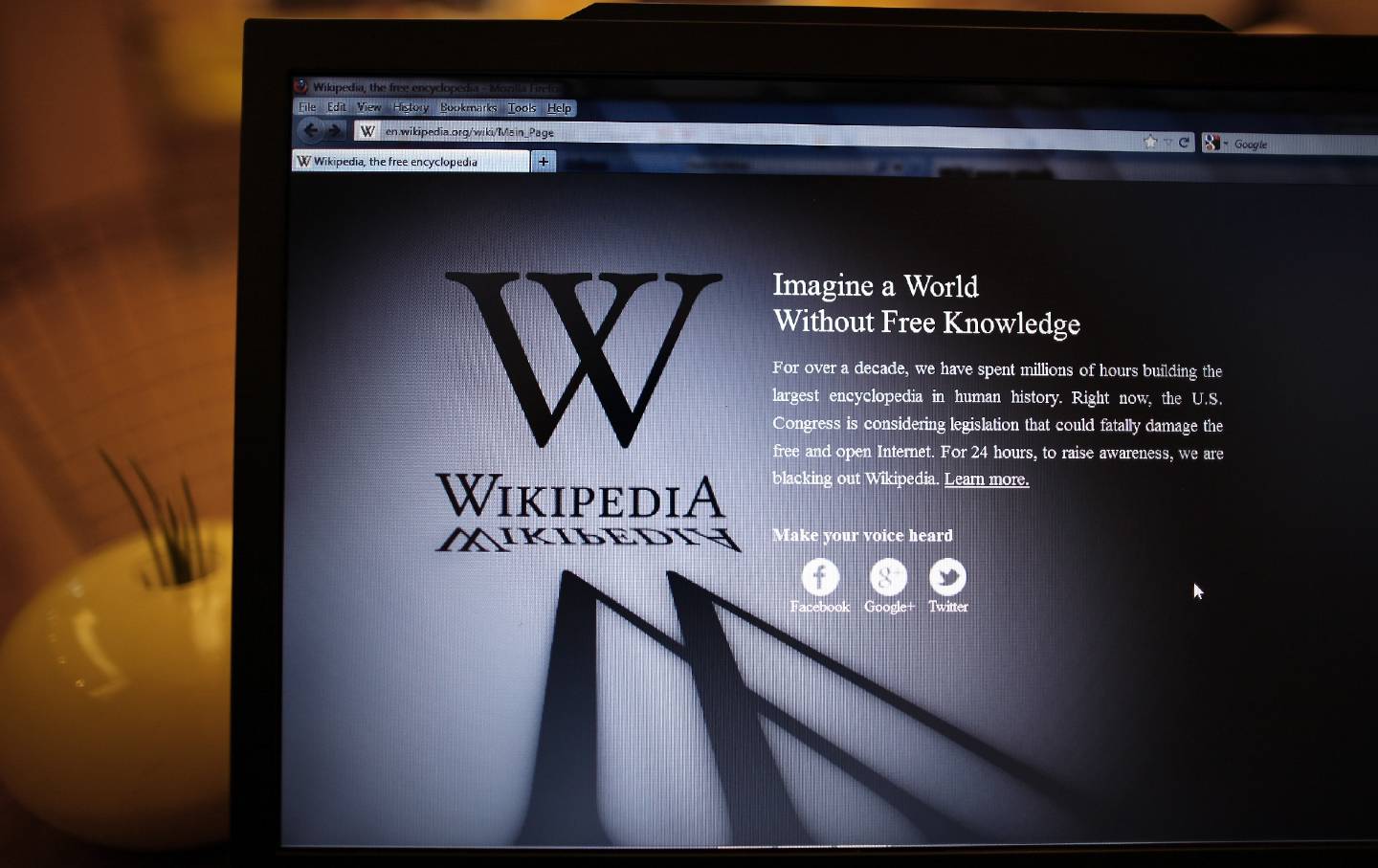

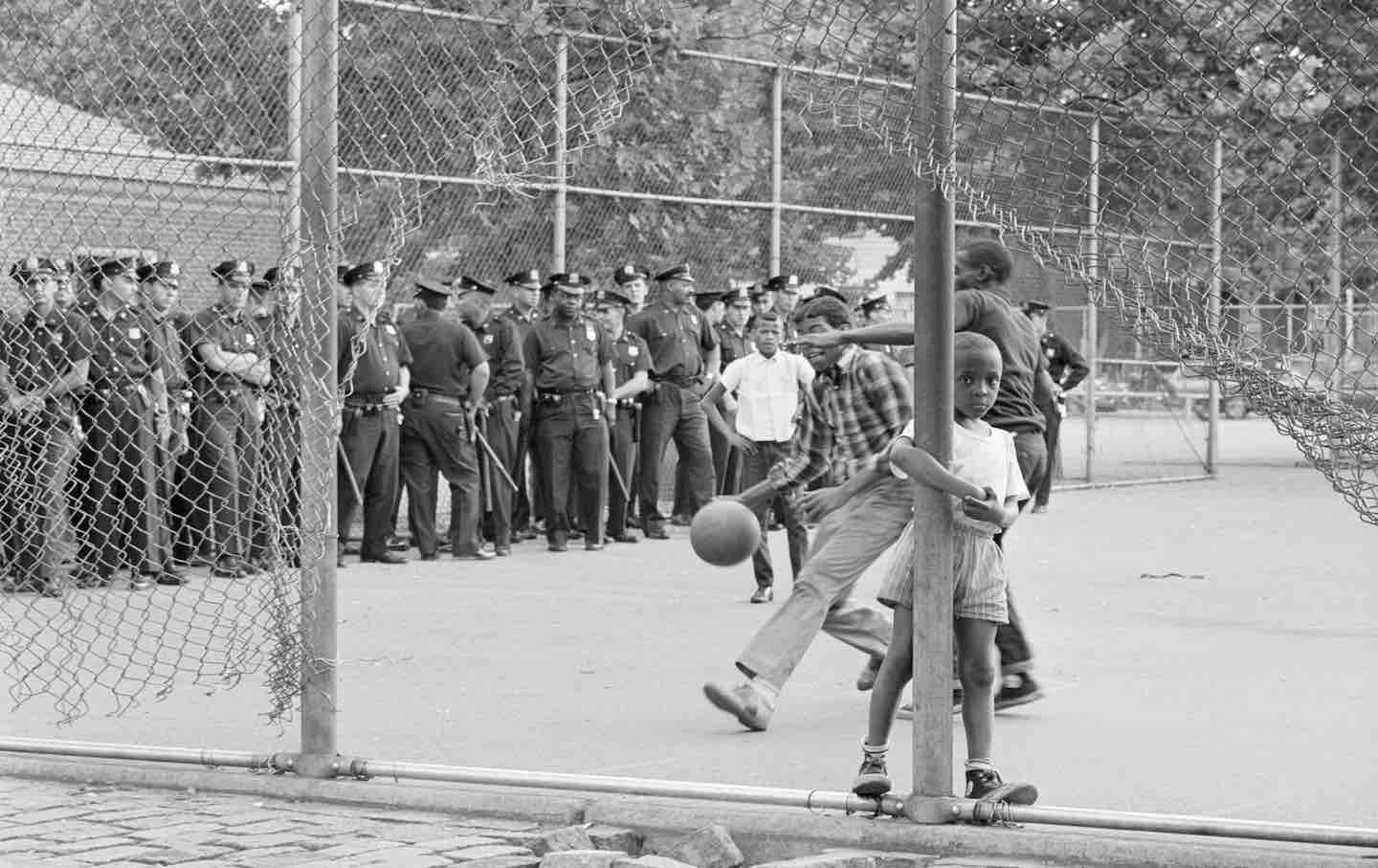

A young boy peers out from a hole in a fence as his friends play basketball in a court where police officers are gathering for a patrol in East New York, 1966.

(Bettmann / Getty Images)In 1993, 128 people were murdered in the Brooklyn neighborhood of East New York, breaking a record for the largest number of individual murder cases in a single NYPD precinct. The city’s murder rate was high in that era—almost 2,000 people were killed that year—but East New York stood out as a hot spot, where children were routinely caught in the crossfire of gang violence. The neighborhood, which comprises about five square miles, was considered not only the most dangerous slice of New York City, but among the most dangerous places in the country.

Books in review

The Killing Fields of East New York: The First Subprime Mortgage Scandal, a White-Collar Crime Spree, and the Collapse of an American Neighborhood

Buy this bookAs crime rates began to decline in 1994, the NYPD claimed that the root of the violence plaguing areas like East New York was the lack of policing of petty offenses (signs of disorder like graffiti or litter), reiterating the now-debunked “broken windows” theory that defined the Rudy Giuliani administration’s stance on crime. It was an explanation that blamed East New York’s predominantly poor Black and Puerto Rican residents, assuming they were responsible either for the drug traffic that fueled so many of the shootings or for standing by as chaos took over. But as journalist Stacy Horn finds in her damning, gripping book The Killing Fields of East New York, the genesis of the neighborhood’s collapse was not a rise in street crime, but rather a white-collar criminal conspiracy that lined the real estate industry’s pockets while destroying what had recently been an affordable enclave for working- and middle-class families.

Horn traces the devastation back to two laws that should have bolstered neighborhoods like East New York and made them more accessible for low-income families of color: the Civil Rights Act of 1968 and the Housing and Urban Development Act of the same year. Instead, as Horn argues, these last pieces of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society program “allow[ed] the design for the perfect financial crime to arise.”

The Civil Rights Act outlawed the housing discrimination, redlining, and blockbusting that had so often barred Black people from homeownership. Meanwhile, the Housing and Urban Development Act sought to further fair housing, in large part by decreeing that the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) could insure mortgages in areas that had previously been redlined—that is, in neighborhoods like East New York, where it had become all but impossible to secure a loan. The unintended consequence of the government’s effort to promote private lending to low-income families of color was, effectively, the creation of the subprime mortgage industry.

In insuring “risky,” or subprime, loans, the FHA inadvertently incentivized realtors, brokers, appraisers, and mortgage-issuing banks to defraud both the government and the very people the government was trying to help achieve homeownership. If the homeowners defaulted, the FHA would pay out the loan in full to the issuer and take responsibility for the vacant, foreclosed building. This created a market for the risky subprime loans, as bad actors colluded to sell dilapidated buildings in “older, declining urban areas” to people who could not actually afford the mortgage payments.

Some officials at the FHA were also eager to gain from the corrupt possibilities of the new subprime mortgage market. Horn locates the origins of East New York’s decimation in a single office building in Hempstead, Long Island, where a particularly corrupt branch of the FHA and an exploitative mortgage bank, Eastern Services Corporation, both happened to conduct their business. Shortly after Johnson signed the Housing and Urban Development Act, Eastern Services began colluding with realtors and credit agencies, as well as with the Hempstead FHA’s appraisers and chief underwriter, to secure loans on rundown buildings for far more than they were worth. The realtors that Eastern Services worked with regularly lured people into unaffordable mortgages for houses where the sewage pipes burst or the furnace died soon after they moved in. As Horn discovered, the conspiracy was extraordinarily cruel: “Buyers were robbed of what little they had and left homeless, more desperate than before.”

East New York was an ideal location to enact this fraud, because it had already been subjected to a racist real estate scheme. Earlier in the 1960s, blockbusting realtors preyed on the prejudices of East New York’s longtime population of Jewish, German, and Italian immigrants, convincing them that they had to sell their homes before the growing number of Black and Puerto Rican families drove down prices, thereby tricking them into selling quickly and cheaply. The realtors then flipped those homes to families of color at inflated prices, and banks redlined the area. What happened in East New York happened all over the country, as white families fled the cities for the suburbs. But what makes East New York sui generis, according to Horn, is the extent of the depredation that followed, as white-collar criminals plundered the neighborhood and city officials failed to step in to stanch the bleeding.

Between 1968 and 1972, when Eastern Services and other banks were issuing scam FHA-backed mortgages, the number of vacant, foreclosed homes owned by the FHA increased exponentially in the neighborhood. The vacant buildings attracted copper strippers, teenage partiers, and arsonists, fueling “a plague of fire.” Instead of repairing East New York, the city gradually withdrew basic services like garbage collection—after all, as Horn points out, the East New Yorkers who could not afford to leave the area “did not comprise a terribly influential tax base.” By 1972, the year Eastern Services and the Hempstead FHA employees were indicted after the FBI and federal prosecutors uncovered their conspiracy, City Hall had already left East New York for dead. In one vivid example, firefighters rushing to flaming buildings had to rely on handwritten directions to find the alarm boxes because so many street signs had been stolen for scrap metal. Those street signs wouldn’t be replaced until almost a decade later, when community members with the East Brooklyn Congregations (EBC) launched a campaign to painstakingly document each missing sign and submit requests to the city’s Department of Transportation. By then, 3,000 street signs in the neighborhood were missing.

As The Killing Fields of East New York compellingly demonstrates, it was the simultaneous decimation and desertion of East New York that created the vacuum in which violent crime proliferated. For decades after the dust on the FHA scandal settled, foreclosed homes—and the vacant lots that cropped up after those buildings were demolished or burned down—were the settings for rapes, shootings, and murders, crimes that the NYPD failed to prevent or solve.

Other authors have recently covered the FHA scandal, most prominently Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor in her 2019 book Race for Profit. As Taylor’s meticulous study illustrates, real estate corruption struck nationwide in the formerly redlined neighborhoods where low-income Black people lived and their desire for affordable, accessible homeownership might be exploited.

The Killing Fields of East New York draws on Taylor’s work, as well as other studies of the scandal and Horn’s original reporting and archival research, to zoom in on how corrupt FHA officials, mortgagees, credit analysts, and realtors colluded to loot one neighborhood in particular. By narrowly focusing on East New York, Horn—a longtime chronicler of the city in books like Damnation Island, about the 19th-century isolation of criminals, the poor, and the mentally ill on Roosevelt Island—accomplishes a rare feat: making white-collar crime and government malfeasance the riveting centerpiece of a work of true crime. As such, the book opens not with the story of the FBI’s investigation of the FHA and the mortgage banks that conspired in the fraud, but with the murder of a Puerto Rican teenage girl in East New York in 1991.

Julia Parker was a vivacious 17-year-old and the mother of a 2-year-old boy, hanging out with friends on the corner of Pennsylvania and Dumont avenues on a hot July day. For about a decade, this had been a “particularly lethal” corner surrounded by empty lots, Horn writes, but it was also a popular hangout spot for teens, near Thomas Jefferson High School and a bodega run by the family of one of Parker’s friends. Just before sunset, a man wearing a black hoodie crouched behind Parker and shot her in the back of the head. She was one of 116 murder victims in East New York that year; her case remains unsolved.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →After a brief prologue sketching out Parker’s murder, The Killing Fields of East New York shifts back and forth, chapter by chapter, between the intersecting stories of East New York’s destruction and the FHA scandal, with Parker’s family history in the neighborhood woven throughout. But Horn’s narrative of the FHA scandal stretches only from 1967 to 1979, while she chronicles East New York from 1966 to 2023. This timeline mismatch creates a disjointed narrative: Whereas Horn interviews some of the federal law enforcement figures who uncovered the real estate scheme in East New York at length, allowing her to describe their investigation minutely, her chapters on East New York’s broader struggles come with much less access to those most affected by the neighborhood’s devastation.

Ultimately, the book’s structure hammers home how, even after federal prosecutors declared victory with the conviction of the owners of Eastern Services and the corrupt officials in the Hempstead FHA office, East New York continued to pay a far greater price than the meager fines and sentences that the white-collar criminals incurred. As Horn sees it, the “organized crime syndicate” behind the FHA scandal was “so effective we’ve never recovered from the damages they inflicted.”

For instance, while Eastern Services owners Harry and Rose Bernstein were found guilty of bribery, conspiracy, and making false statements in 1974, a lenient judge reduced Rose’s four-year prison sentence to a year and a day, and Harry’s five-year prison sentence to 18 months in a community treatment center, with release each weekend. In the end, the Bernsteins and their company were fined just $685,000 for their involvement in a conspiracy that resulted in 2,500 foreclosed homes and cost the federal government approximately $200 million. Meanwhile, 1977—the year the Bernsteins finally began serving their light sentences—was a horror for East New Yorkers, who staged crime-prevention rallies in the aftermath of two heinous child murders, which remain officially unsolved. Horn quotes a New York Times column from that year that declared that “East New York, where the buildings are withering fast as a life-sick forest,” was being “put to fast death by fire and abandonment.”

The Killing Fields of East New York also attests to how the justice system continued to treat white-collar criminals with kid gloves after the FHA scandal, even as their actions created an environment for street crime to flourish. In 1989, when the Bernsteins’ son Louis pleaded guilty in a federally backed mortgage fraud case suspiciously similar to the scam his parents had run, he received a prison sentence of just five months and was fined $20,000. By then, East New York had been transformed into a particularly violent front in the crack cocaine epidemic—inexpensive crack flooded the neighborhood, and dealers and users occupied the abandoned buildings that increasingly studded residential blocks. “There was so much crack you could smell it through the walls,” one resident recalled. The vacant lots that covered 20 percent of the neighborhood made for open-air shooting galleries. As organizations like the Local Development Corporation of East New York attempted to renovate these vacant buildings before they could be torn down to create more empty lots, the city was of little help. Horn writes of a LDCENY program director calling the local NYPD precinct after drug dealers had replaced the padlocks on one building mid-renovation; instead of officers responding immediately to cut the locks, the director was initially told to ask contractors to block the entrance.

That year, Julia Parker turned 15, gave birth to a baby boy, and dropped out of high school. She’d soon follow the path that many other East New York teens took: running drugs, where one could net up to $500 a day. “They didn’t see the dark side of working in the drug trade,” Horn writes. “They saw their parents living life on the edge of poverty, working day in and day out for low pay.” Horn writes that Parker’s involvement with the cocaine trade likely led to her murder.

The most infuriating and tragic aspect of the devastation of East New York is that it was entirely preventable. “It’s not that no one saw this coming,” Horn writes—the warning was sounded decades before by the federal government itself in the Kerner Commission report. Johnson had ordered the creation of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders following the civil unrest of 1967, and the commission, led by Otto Kerner Jr., issued a report that had paved the way for the Civil Rights and Housing and Urban Development acts. The report pointed the finger at the white-dominated institutions—like the real estate market—that created, maintained, and excused the segregation and poverty of racial ghettos. Dr. Kenneth B. Clark, who was asked to speak to the commission, issued a grave warning to the report’s authors, one that underlined how federal policy alone could not address the costs of generations of racial inequality: “If human beings are confined in ghetto compounds of our cities and are subjected to criminally inferior education, pervasive economic and job discrimination, committed to houses unfit for human habitation, subjected to unspeakable conditions of municipal services, such as sanitation, [then] such human beings are not likely to be responsive to appeals to be lawful, to be respectful, to be concerned with property of others.”

But as Horn reminds her readers again and again in The Killing Fields of East New York, America never took these warnings seriously. Instead of supporting homeownership for low-income families of color, as the 1968 laws required them to do, FHA officials nationwide collaborated in schemes that only compounded the issues facing neighborhoods like East New York. And when the scandal was uncovered, it was all too easy for politicians to claim that they had tried to support fair and equal housing, but that “unsophisticated buyers” who didn’t understand the responsibilities of homeownership had left the taxpayer footing the bill. It’s little wonder that when the next subprime mortgage industry exploded some 40 years later, no investment banks were indicted. East New York was another casualty of the 2008 financial crisis: The area’s foreclosure rate hit 52 percent some years after the Obama administration swooped in to save the investment banks. Horn touches only lightly on how East New York is faring in the present day; most of her contemporary chronicle deals with the cold case of Parker’s murder. But what she does include is revealing: Community organizations like the EBC continue to lead the way in developing the neighborhood, especially in constructing and renovating affordable housing. Residents remain wary of promises from city officials, which have so often failed to produce material change. And the murder rate, though much decreased from its 1993 peak, is still the highest in the city.

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation