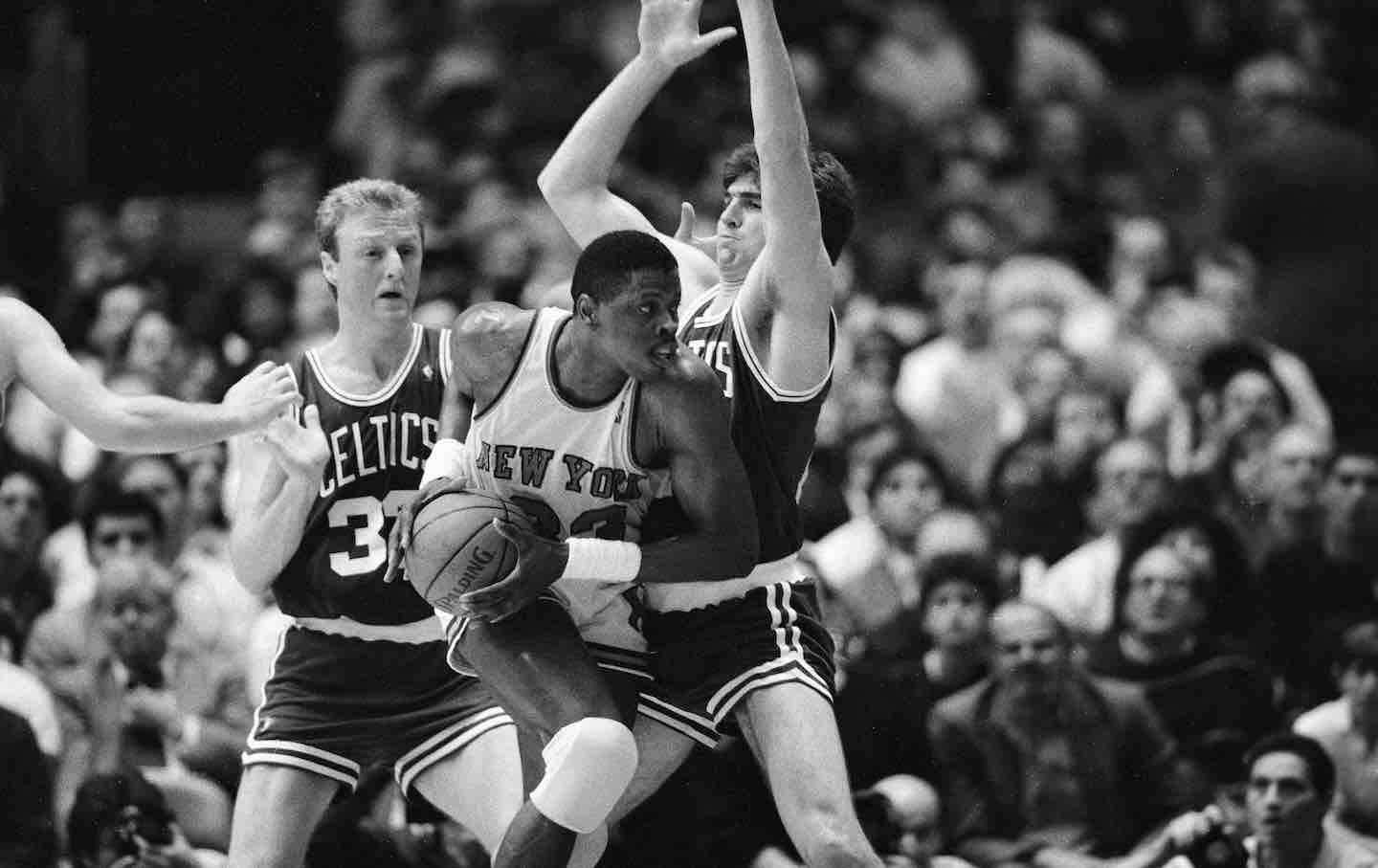

Patrick Ewing makes a move against Larry Bird and Mark Acres. (Photo by Bettmann / Getty Images)

The Miami Heat are the hardest-working team in today’s NBA. If you pay attention to the league, you will consistently hear this message. It’s an identity sold by the team, its players, and the media in and outside of Miami. The organization gets the best out of its players because of a militaristic approach to conditioning and a team-first attitude and tireless work ethic. This is “Heat Culture.” It’s not for everyone, only those willing to put in the work.

In Heat Culture, players are held accountable by their coaches and teammates, and vice versa. In March of this year, Jimmy Butler—the perfect avatar for Heat Culture—got into a public spat with head coach Erik Spoelstra and Heat lifer Udonis Haslem.

The Heat were losing to the Golden State Warriors, who were playing without Stephen Curry, Klay Thompson, and Draymond Green. After a 19-0 run by the Warriors, Butler began yelling at Spoelstra in the huddle. Haslem, backing up Spoelstra, threatened to fight Butler. In the postgame interview, Spoelstra explained the altercation by saying,“We have a competitive, gnarly group and we were getting our asses kicked.”

For any other team, such an incident would seem like a public fracturing, but for the Heat, it was framed as a positive consequence of their identity. By the next game, all three were smiling and joking together again.

Reading Chris Herring’s book Blood in the Garden: The Flagrant History of the 1990s New York Knicks is a good way to understand where the current iteration of Heat Culture comes from, and how the general worship, by commentators and fans, of toughness, grit, and other sports clichés emerged.

Pat Riley, the former Showtime Lakers coach, Knicks coach, and current Miami Heat president, made the New York Knicks into one of the premier teams of the 1990s by instituting a similar atmosphere of hard work, physicality, and a defense-first mentality. There was also an abiding element of violence and retribution, back when bare-knuckle aggression was still permitted in the league.

In the book, Riley and the Knicks are portrayed as almost mythical characters. They are giants among men whose failures and successes were born from their innate character. Herring’s history is supposed to be a moral tale about the way basketball used to be played, and the virtues that its commentators still hold up. But it also paints an image of a bygone time that is both romantic and archaic. It’s a time that is easy to look back on fondly because there has thankfully been tremendous progress made in terms of the care and protection of players—of their health, mental and physical.

Herring’s history of the 1990s Knicks begins with the team’s architect, Pat Riley. The explanation of his personality, his so-called toughness, begins with a story of him at 9 years old, hiding in the garage at home for hours after being chased by a bully who was wielding a knife. At the dinner table that evening, Riley’s father told the young boy’s older brothers to take him back to the park the next day. The father had seen enough of his son being bullied and wanted him taken back to the park in order for the boy to confront his bullies and learn to face his tormentors head-on. Forever after, he saw himself as a fighter.

Riley, being a tough guy, was attracted to others with the same moxie. He decided to marry his former girlfriend Chris Rodstrom two years after taking her to a boxing match. She wore a white dress to the match, and during the fight, blood from the combatants splattered on the dress. When Rodstrom remained unfazed by the incident, Riley told himself, “This is my kind of girl.”

Though he was the conductor behind one of the most entertaining dynasties in NBA history with the Lakers of the 1980s, Riley’s inspiration for his philosophy with the Knicks came from that team’s antithesis: the hardscrabble and dirty-playing “Bad Boys” Detroit Pistons, who won championships through brutality as much as skill. So the mythology of Riley depended less on something original than something borrowed, in effect the desire to take violent ambitions that had been successful somewhere else and give them his own personal sheen.

From the start, the Knicks players learned how demanding Riley could be. He wasn’t “a coach who concerned himself with pacing. Rest days weren’t a consideration. Every game was a battle, and every battle had to be won.”

Herring describes the scene after the first 15 minutes of Riley’s first training camp experience with the team:

Each Knick would take part in “17s,” which meant seventeen sideline-to-sideline runs in under a minute’s time, briefly resting, then repeating the process over and over until the coach saw fit. A few players grew light-headed from the exertion and sweltering conditions in the gym, which left the floor so wet that the team was forced to move to another court during practice.

So much of the book is, understandably, focused on Riley and his mystique, but he is only part of the story. Along with detailing the behind-the-scenes drama, Blood in the Garden examines pivotal games and series during the Knicks’ run, and stars like Patrick Ewing, Charles Oakley, John Starks, Mark Jackson, Doc Rivers, Charles Smith, and Derek Harper all get their own heroic stories. While they don’t stand as tall as Riley in the book, they do receive similar grandstanding treatment of their unique characters and their individual successes and failures.

John Starks’s impulsive nature is traced back to his childhood and showcased through an encounter with a white classmate when he was a sixth grader in Tulsa. The classmate knocked Starks’s books out of his hands, and when Starks told him to pick them up, the boy called Starks the n-word. Starks fought back and beat him up. He was suspended for his reaction and told to leave school, but on his way home, he took the wrong bus. When he realized his error, he used the last bit of money he had to go in the opposite direction. He eventually found his way home by using landmarks that he recognized.

Charles Smith, Patrick Ewing and Charles Oakley of the New York Knicks, 1994. (Photo by Al Pereira/Getty Images/Michael Ochs Archives)

This memory reveals that Starks “was someone who often dug his heels in and doubled down on things, even in moments when he appeared to be totally lost.” The story is used as the prologue for why an ice-cold Starks kept shooting against the Houston Rockets in Game 1 of the 1994 NBA Finals. Houston won the game and Starks finished three for 18, with 10 straight misses.

Like Riley and others, Starks had a personality that accounted for both his successes and his failures. He went six for 11 in the next game, which New York won. More importantly, because his shooting ran hot and cold from game to game and quarter to quarter, Riley, who was loyal, kept his mercurial shooting guard in the games and allowed him to keep shooting even when he struggled—sometimes to the ultimate detriment of the team.

Although Anthony Mason wasn’t the biggest name on the team, at least in the beginning, none of the players are given a bigger heroic treatment in the book than he is—mainly because out of everyone, Mason has the most mythical and tragic story to tell and is representative of what those New York Knicks were. He was their avatar.

Mason is shown as both the symbol of all of Riley’s principles and also his most consistent enemy outside of management and Riley’s own paranoia. Mason began as a relatively unknown training camp invitee but turned into a central figure for the Knicks on offense and defense especially. But where Riley was tough and controlled, Mason was tough and explosive. The first chapter of the book begins with Riley looking ruffled during his first practice because Mason was trading blows with Xavier McDaniel.

More fights would ensue. Mason fought with teammates, with coaches, and with Riley, who suspended him several times. In a chapter titled “The Enigmatic Life of Anthony Mason,” Herring goes through a history of Mason’s life, in and outside of basketball, and relates how his reckless behavior was also accompanied by sensitivity.

When he was in college, Mason cussed out his coach at Tennessee State for subbing him out after a careless turnover. When he sat down on the bench, tears filled his eyes. He was sad, not because he was angry but because it was his last game with the school and his mother had made the trip from New York to see him play in person for the first time.

He got in constant trouble at school, was bailed out from jail several times, borrowed and crashed a teammate’s car, and generally was a handful for coaches, teammates, and friends. He fought people at bars, flattened his own son when the young boy challenged him to a basketball game, and was arrested on charges of statutory rape—which were ultimately dismissed when DNA evidence failed to link him to the crime.

In the most serious incident in the book, Mason almost died in a car accident and almost killed several others when he totaled his white 560 Mercedes-Benz after drinking and driving at over 100 miles per hour on the highway. There were five people in the car, all of whom miraculously survived. Mason was saved from imprisonment by some friends who were in a car behind him: They loaded him up into their car and drove away before the police arrived.

On the other hand, after college teammate Cordell Johnson shared his ties and dress slacks with Mason, who didn’t own any because he grew up poor, Mason shared everything he had with Johnson as an act of gratitude. He was a womanizer, but he was also the consummate wingman. One of his teammates married the woman Mason introduced him to.

He could be stern with his children but loved them deeply. He was very religious and went to church regularly, often ending his days in prayer. He was dedicated to his mother and would make late-night stops to leave thousands of dollars on her dresser. He made time for beat reporters and sometimes bought them drinks. He always had time for children, especially those less fortunate, whom he saw as a reflection of himself and his childhood. Patrick Ewing famously refused to sign autographs for kids in public, and Mason is reportedly still mad about that, well into retirement.

Reading Blood in the Garden was similar to watching Michael Jordan’s Last Dance, in the sense that it is a behind-the-scenes look at some of the most iconic basketball players and teams in NBA history, but it is also an exercise in burnishing a legacy—making a legend out of what was much less glamorous, much more ordinary. It’s a process that is almost unavoidable in sports, and history can remain so stagnant and sacred that any accusation of something being “less than” is likely to incite ire, or at least a fresh round of screaming matches on ESPN. That is another way of saying that it is hard to look back at different eras of sports with fresh eyes, because so much of its history is written through rose-tinted lenses.

Mason and Riley are the great embodiments of this problem. As the book is written in reflection, it begins with the premise that these men were almost supernatural, men unlike other men, larger than life, and then uses their character and personality to explain what happened to them and the team. It could very well be an ancient Greek epic poem.

This problem isn’t necessarily a bad one. It’s unavoidable in sports discourse because sports are an arena for mythmaking, and considering the power that individual players and coaches can have over the fate of a team, it makes sense that the storytelling follows the emotion of witnessing great players and coaches take a middling team and transform it into one of the best in the league over a handful of years. Heroic stories, tales of individuals bending the world to their will and overcoming their station through their unique genius and perseverance, especially as a man, are one of the most consistent narratives that human beings exchange, and sports present endless opportunities involving content and characters for that.

It can’t be dismissed that the brutality and violence of the 1990s NBA, and of the Knicks in particular, appeal to a certain idea of masculinity. They were men playing like men, beating each other and outdueling their opponents rather than shying away and complaining. If one isn’t careful while reading the book, it is possible to come away repeating the mantra of many retired NBA players these days, saying that they just don’t make players like that anymore.

Looking at the consequences of that kind of play, and that view of being a man, in terms of shortening the physical careers of many players and the mental health issues that they suffered in silence—or suffered while others looked at their reckless behavior as just personality quirks—it feels like a great thing for the league and for the world that we have moved beyond that time.

Still, the bootstrapping story of the Knicks remains appealing to a certain sort of fan. In the current era of NBA basketball fandom, everything has been reduced to a question of “rings.” It is an extreme way of looking at the world of sports, which champions ultimate glory, because everyone dreams of winning but knows that ultimate glory is often beside the point. It would only take a few minutes of conversation with an NBA fan of a team that doesn’t win often for someone to realize what people truly want from sports.

What people want from their team, at least if the team isn’t going to be a perennial winner, is a great story. They want characters who can win them over, and a team that has an identity a person can aspire to and embed themselves in—an identity that can make them feel part of something great, something representative, something with purpose.

The Knicks were failures in the sense that they never reached the ultimate glory they aspired to. But failures are often important. The underdog, the hero, doesn’t always have to succeed to end up immortalized. An underdog can become a symbol—a symbol that endures through the changing times.

Zito Maduis a writer living in Detroit.