A Snapshot of a Mother’s Life in Gaza Under Occupation

Khawla Ibraheem’s play A Knock on the Roof examines how the Israeli military terrorizes Palestinians in their most intimate and private spaces: their homes.

Khawla Ibraheem in “A Knock on the Roof.”

(Joan Marcus)

Exposure desensitizes. The repeated sight or expression of a horrific scene or idea might, at first, elicit shock or outrage or sorrow. Then, quickly or slowly, our emotional responses are dulled. The process is aided sometimes by euphemism, which works in the other direction: to swathe horror in a gauzy film.

A “knock on the roof” is one such euphemism. It describes a practice developed by the Israeli army, used widely in its occupation of Palestinian lands. But to understand what it means, one must first understand the architecture of a typical Palestinian town, village, or camp. Space is limited in Palestine, and families are large. People tend to build four- or five-story apartment buildings to house an entire extended family. In many cases, these homes are works in progress: Children will build new floors to house their own growing families, so that multiple generations live in a single building.

In the roof-knock procedure, the Israeli army will deploy a military drone to shoot a small explosive onto a structure’s roof—the “knock.” The inhabitants then have five, 10, or 15 minutes to evacuate. After that, the building is targeted with a much larger munition—a laser-guided bomb, for example—and completely destroyed.

The Israeli army claims this practice is humane. Its intent, they say, is to “minimize civilian casualties in Gaza.”

News reports and firsthand accounts from survivors equip us with the tools to begin to understand what the experience may be like. Imagine a crash on the roof just past midnight, with your children asleep in another room. You sprint to assemble your family and escape with whatever belongings you can pack before, within the next several minutes, a bomb destroys your home. The experience is shocking but fathomable. Our imaginations do not need to travel far to grasp the terror.

Khawla Ibraheem, a Syrian Palestinian playwright and actor from the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, wrote A Knock on the Roof to illustrate the reality—how inhumane it is, and how universal the terror may be. In the one-woman performance, Ibraheem plays Mariam, a mother in Gaza who lives in an apartment building with her young son, Nour, and her own mother. Her husband, Omar, is away completing a master’s degree; he calls them regularly to check in. Ibraheem voices all four characters, infusing each with depth and dimension.

The story follows Mariam’s increasingly frenetic and obsessive routine preparing for the knock. She packs essential items for herself and for Nour: a change of clothing, a toothbrush. She races up and down the building’s common stairwell, keeping time to gauge how far she can run in five minutes—the time she believes she may have before the second strike. The sequence is repeated endlessly across the play’s 85 minutes as Mariam trains, like an athlete, for the most consequential sprint of her life. She also recruits her mother and her son as her preparations grow more and more elaborate.

These two characters are used as foils; they help deliver critical insights into life during bombardment in Gaza. For example, Mariam’s mother admonishes her to wear a thobe, the gown that many women in Palestine wear, while showering. Her concern: that should the home be destroyed while Mariam is in the shower, her body may be discovered naked, an indecency. It’s a minor detail, but one that illustrates the totality, the all-consuming reality, of the occupation for the Palestinians who are forced to endure it. Their homes are not private. Their minds are occupied.

Mariam captures the emotional tenor of the experience, a kind of stultifying boredom saddled with anxiety, when she describes life in Gaza, an open-air prison: “Time feels endless, but none of it belongs to you.”

Yet there is an unexpected playfulness to Ibraheem’s performance—she tells wry jokes and bounds energetically from place to place—that prevents it from slipping into bathos or didacticism. She succeeds as well in rendering the voices of Mariam’s mother, son, and husband, imbuing them with life, like a friend telling you a story and spicing it up with impressions. She adopts a comic, exaggerated voice when mimicking Mariam’s mother’s speech. She whinges, like a 6-year-old, when Nour is speaking. The intimate setting, at the New York Theatre Workshop in the East Village, highlights her strengths as an actor.

Oliver Butler directed the performance. His spare use of lighting produces a range of effects. Sometimes the lights are deployed to highlight Mariam’s flouncy mien in coordination with a simple, evocative score. And sometimes they are used to broaden the stage and engage the audience—as when Ibraheem steps out of character to initiate brief, light-hearted exchanges with members of the audience with the lights up. Shadow is also used to great effect, enhancing the background and altering the emotional tenor: The play can swing from high drama to comedy through the use of darkness and light or a narrow or wide aperture on the spotlight lens.

The play began as a 10-minute monologue that Ibraheem wrote in 2014. According to the show’s program, it was “inspired by motherhood, war and the Israeli army’s tactic of ‘roof-knocking’” in the aftermath of Israel’s war in Gaza in 2008–09. In 2019, Ibraheem met Butler at the Sundance Theater Lab; she was there to workshop a play, London Jenin, which debuted at the Freedom Theater in Palestine. Ibraheem and Butler reconnected in 2022 when she began working to expand the monologue. Butler took on the role of director and helped bring the work to the stage.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The full production was set to debut in Haifa in October of 2023, but it was canceled after the war started. The cancellation is noteworthy—a play about Palestinian humanity could not be performed in Haifa, a historic Palestinian city within Israel, during a genocide. According to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, there has been mass state repression and coordinated mob violence targeting Palestinian citizens of Israel since October 7, 2023. Any reading materials containing “expressions of praise, support, or encouragement of terrorist acts, direct calls to commit an act of terrorism, as well as documentation of an act of terrorism” have been banned by Israeli authorities. According to the report, “to implement the law, the police have started confiscating phones from [Palestinians with Israeli citizenship] and scrolling through their social media accounts and chat groups for evidence of violations of the law.”

Indeed, because A Knock on the Roof was written before the genocide, it acts as a window onto a different time, when Israeli forces didn’t routinely exterminate entire families as a matter of policy. Roof-knocking was used in conflicts in Gaza in 2006, in 2008–09, in 2012, and in 2014. But it has not been used in the past 15 months, as the Israeli military oversaw the destruction of the Gaza Strip. On January 18, 2025, The Guardian reported that “nine in 10 homes in the territory have been destroyed or damaged” and that “schools, hospitals, mosques, cemeteries, shops and offices have been repeatedly hit.”

Israel’s abandonment of the roof-knocking procedure doesn’t necessarily need to be recounted or noted in Ibraheem’s play, but it occurred to me repeatedly as I watched it. The genocide mediates any understanding of the play, and its absence in the narrative is notable.

A Knock on the Roof represents an effort to combat the desensitization, the reduction in feeling, that a normal person experiences through learning that yet another family has been killed or another building destroyed in Palestine, in a far-away conflict. It’s an effort to access sites of empathy, to highlight just how ordinary the people in Palestine are.

When the play succeeds, it is through common touchpoints: the exposure that a person feels on the toilet; the back-and-forth quality of a mother-child exchange; the disorientation that one experiences at being awakened suddenly.

The evocation of others’ lives—and how like your own they may be—is folded into the play. In one scene, Mariam leaves her apartment and comes across a destroyed home in the course of her meanderings through the neighborhood. She observes the everyday items in the rubble—a prescription, an article of clothing, a child’s toy—and begins to imagine herself among her own belongings, the artifacts that every person collects in the course of living. The audience is encouraged to imagine the items they’d pack for a sudden trip—one from which they cannot return.

For all of the play’s strengths, there are opportunities for greater precision, too. In one scene, Mariam is stopped and questioned by a man with a gun. We’re not told if he’s a police officer (which in Gaza means someone identified with Hamas), a militant associated either with Hamas or some other group, or even a member of a gang. In the exchange, Mariam exhibits fear at the encounter, and the man with the gun admonishes her to wear a headscarf. The scene sits ambiguously, incongruously, in the scheme of things. Is it a criticism of Hamas? Or a concession to the dominant Jewish Israeli conception of life in Gaza under Hamas?

Still, the play is a meaningful contribution to the catalog of Palestinian resistance art. At its most successful, it pulls the viewer into the ordinary perspective, the everyday life, of a person who is subjected to extraordinary circumstances. What would you take with you? What are your personal artifacts? What are the milestones that describe a life in progress?

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks

The late actor and director leaves behind a roster of classic films—and a much safer and juster California.

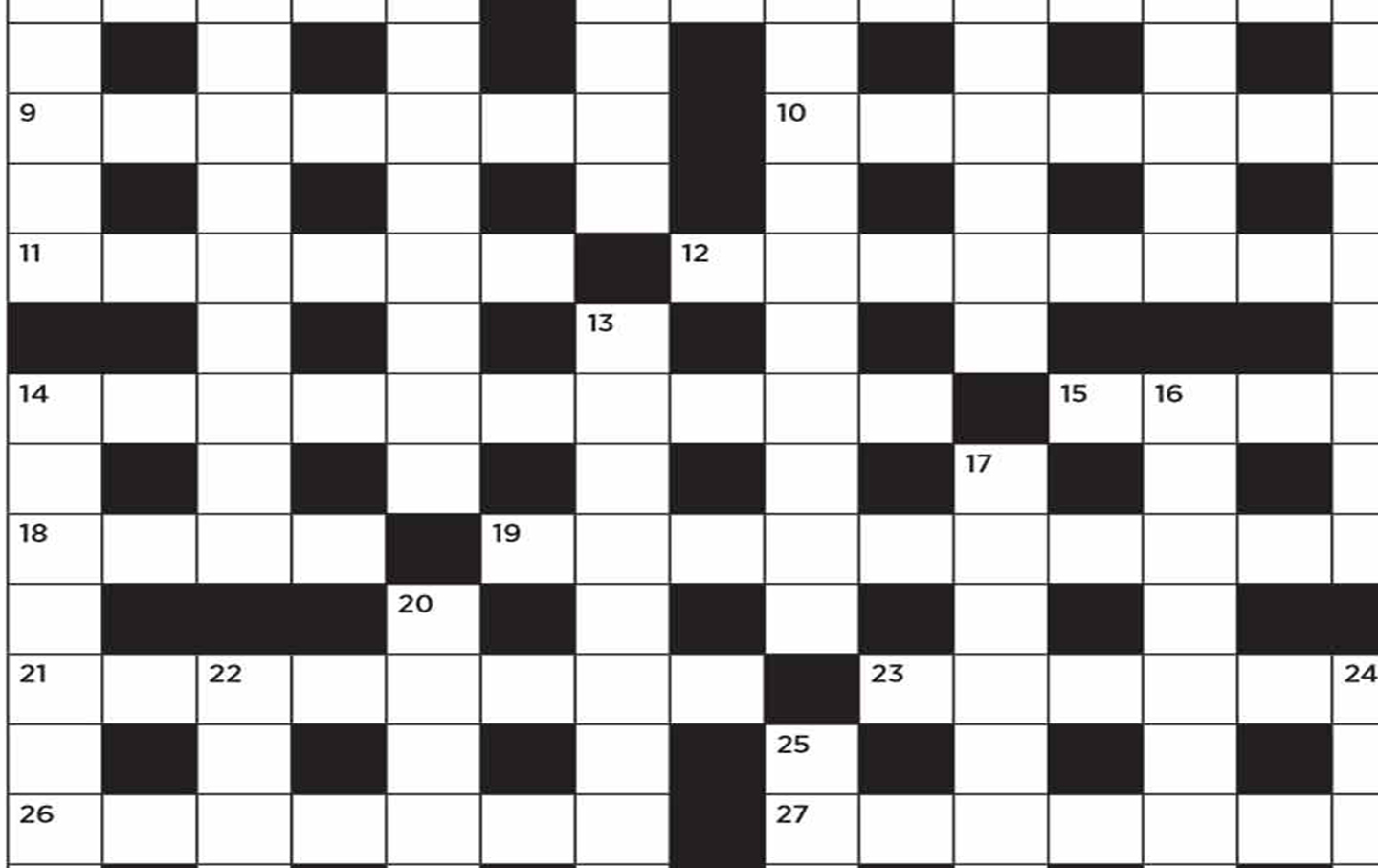

Solution to the “Big Event” Crossword Solution to the “Big Event” Crossword

If questions remain after reading this, please write to sandy @ thenation.com.

Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments

Dev Hynes moves between grief and joy in Essex Honey, his most personal album yet.