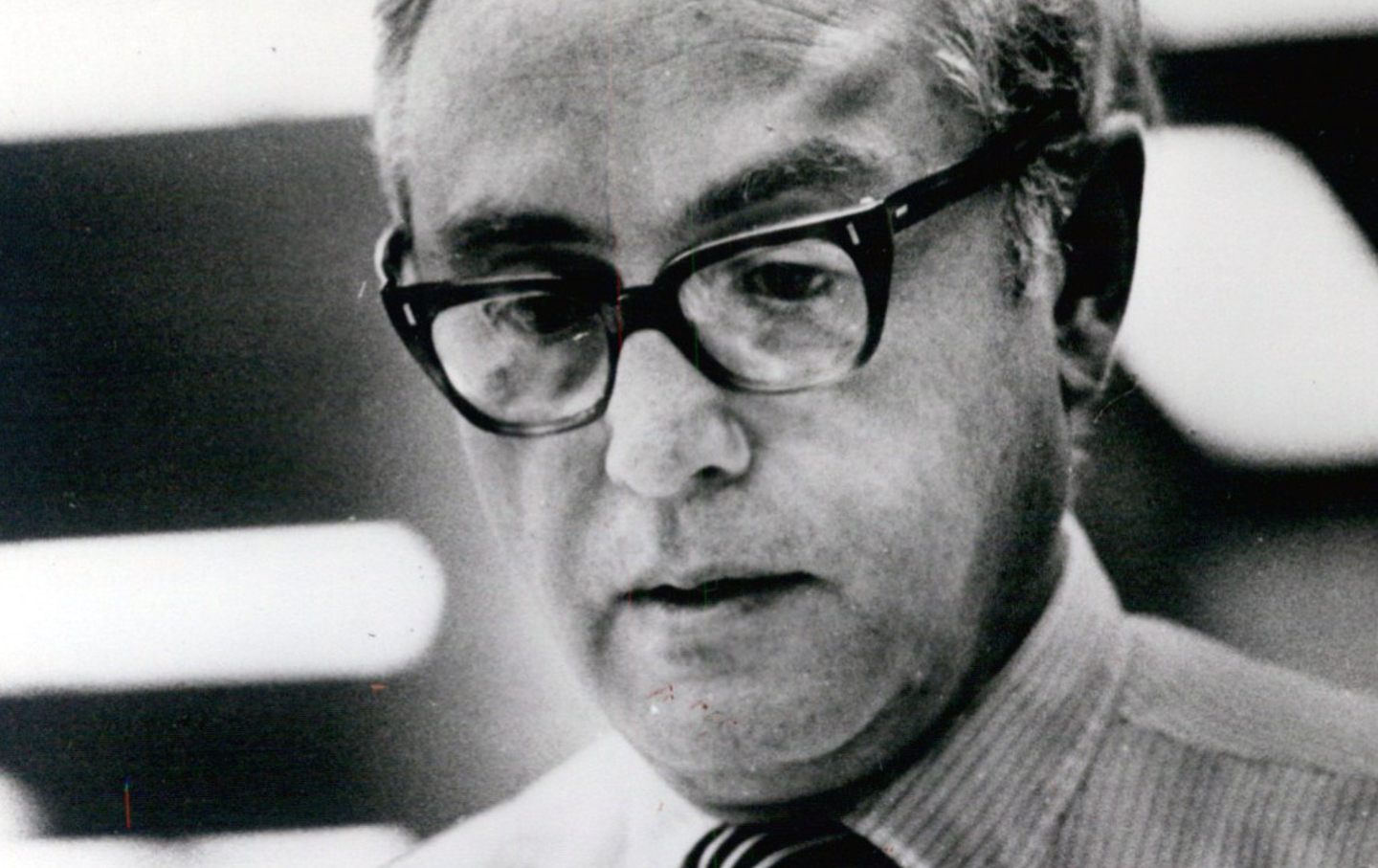

Kris Kristofferson circa 1970.

(Michael Ochs Archives / Getty Images)

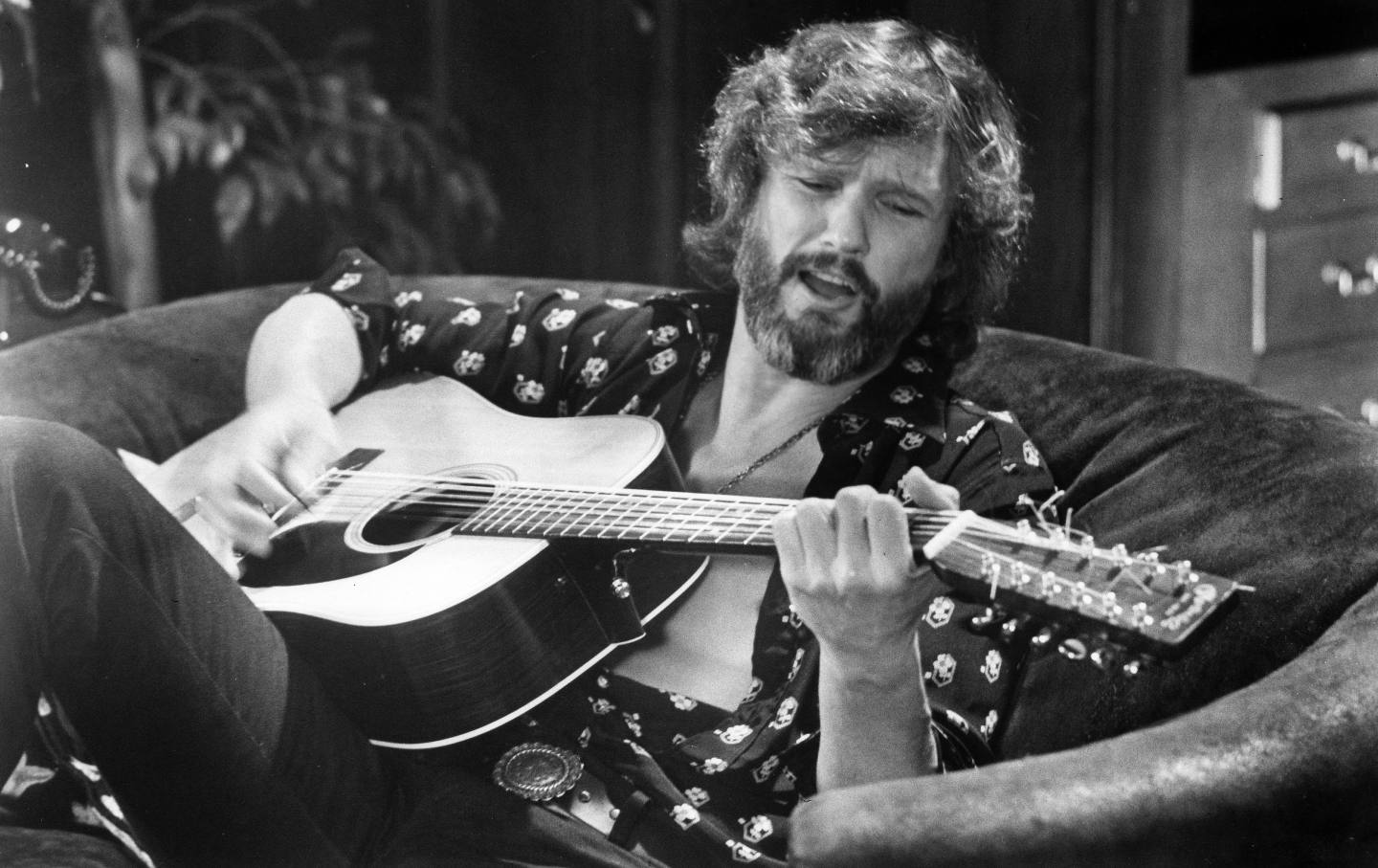

As I was making dinner Sunday evening, I was streaming an Apple-branded country station through our home wireless setup, and “To Beat the Devil” from Kris Kristofferson’s 1970 eponymous debut record came on. (This is not to be confused, by the way, with the long-running column that Alexander Cockburn wrote for this magazine called “Beat the Devil,” named after a John Huston caper film with a screenplay written by Cockburn’s then-blacklisted dad based on his novel of the same name.) I relished, as always, Kristofferson’s gruff, tune-challenged voice as he delivered a talking blues narrative reprising his career as a starving artist in Nashville. The opening lines of its chorus—a taunt from a regular in a Nashville bar who challenges Kristofferson’s crusading bard ethos—seemed particularly apt for a political journalist covering the present deranged presidential cycle: “If you waste your time a-talkin’ / To the people who don’t listen / To the things you are sayin’ / Who do you think’s gonna hear?”

Midway through the second verse, I idly grabbed my phone as I waited for a pot to simmer, and saw the news that the very man recounting the struggles of getting heard in Music City had died. The news lent a still more apt meaning to the song’s closing lines, which are the singer’s answer to his barstool critic: “I was born a lonely singer and I’m bound to die the same / But I’ve got to feed the hunger in my soul / And if I never have a nickel, I won’t ever die ashamed / ’Cause I don’t believe that no one wants to know.”

Kristofferson’s own life was unlikelier than any country song. A Texas transplant growing up in California, he studied literature in college, and earned a Rhodes scholarship. He started playing music in England under the name Kris Carson, as a rock act—and then enlisted as an Army helicopter pilot during the Vietnam War. After his discharge, he moved to Nashville and worked as a janitor at Columbia Recording Studios; that gig landed him a front-row seat at the sessions for Bob Dylan’s landmark 1966 album Blonde on Blonde. Though he didn’t meet Dylan then—“I didn’t dare talk to him,” Kristofferson recalled; “I’d be fired”—he saw Dylan finish writing “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” alone at a piano in the dead of night.

He became less starstruck over time; While he was working as a helicopter instructor for the National Guard, Kristofferson detoured a helicopter onto Johnny Cash’s front yard, to drop off demo tapes of two recent songs: “Sunday Morning Coming Down” and “Me and Bobby McGee.” The ploy worked; Cash recorded “Sunday Morning” in 1970, and it won Song of the Year honors at the Country Music Association that year. Remarkably, Ray Price had also won Song of the Year from the rival Academy of Country Music for his cover of Kristofferson’s “For the Good Times” the same year. By that time, Kristofferson had recorded his own debut album, and to top it all off, Janis Joplin covered “Me and Bobby McGee” on her posthumously released album Pearl the following year.

From there, the songs—if not always the hits—kept on coming. The Silver-Tongued Devil and I, released in 1972, is arguably his strongest record, with the puckish “Pilgrim Chapter 33” an early foray into what would later be known as outlaw country, and “Epitaph” one of the most anguished remembrances of Janis Joplin in song. (In the same vein, Kristofferson’s “Why Me,” from 1973’s Jesus Was a Capricorn, stands out as a wrenching personal testimony in the otherwise hackneyed field of modern country gospel.) Throughout the many later turns of his career, he remained the same lonely singer and intimate chronicler of everyday misfortunes that he was at the start. Later efforts, such as The Austin Sessions (a self-tribute album of sorts, recorded with stripped-down instrumental backing in 1999) and This Old Road (2006) were steeped in the same restless, self-questioning sensibility.

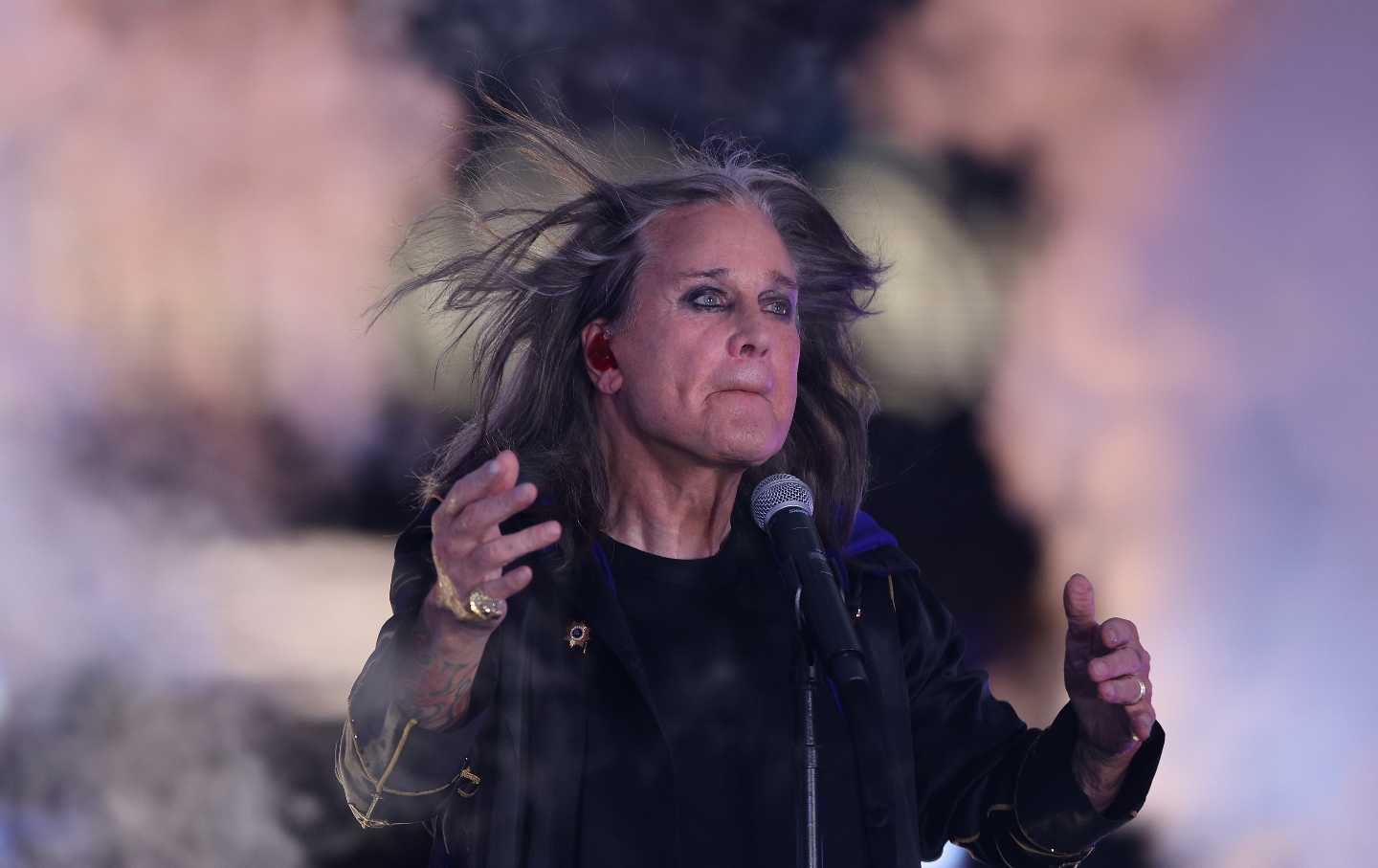

Kristofferson’s overnight siege of the country music scene soon segued into a film career; the former Columbia janitor appeared opposite Bob Dylan in Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid in 1973, and as Ellen Burstyn’s love interest in Martin Scorcese’s 1974 film Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. In 1976. he starred with Barbra Streisand in A Star Is Born—the blockbuster role now name-checked in all his obituaries. After appearing in Michael Cimino’s train-wreck 1980s epic Gates of Heaven, Kristofferson took on more journeyman roles; he’s probably best known to younger media audiences as Wesley Snipes’s vampire-slaying sidekick in the Blade franchise.

What’s most striking about Kristofferson’s long and accomplished career, though, is that he remained throughout the same crusading songsmith who narrated “To Beat the Devil.” In an age of frenetic country mainstreaming—and a ceaseless barrage of Lee Greenwood–style pseudo-patriot pandering—Kristofferson was an arch and eloquent critic of American callousness and hubris, at home and abroad. An anecdote from a profile written for Rolling Stone by actor Ethan Hawke lit up the social media sphere after Kristofferson’s death announcement. At a Beacon theater concert for Willie Nelson’s 70th birthday, a New Country star who’d recently charted his own jingoistic ’Merca hit—most likely Toby Keith—brushed by Kristofferson backstage, and growled at him, “None of that lefty shit out there tonight, Kris.” When Kirstofferson growled back, “What the fuck did you just say to me?,” the New Country tone policer stalked away and the following exchange ensued, in Hawke’s remembrance:

“Don’t turn your back to me, boy,” Kristofferson shouted, not giving a shit that basically the entire music industry seemed to be flanking him.

The Star turned around: “I don’t want any problems, Kris—I just want you to tone it down.”

“You ever worn your country’s uniform?” Kris asked rhetorically.

“What?”

“Don’t ‘What?’ me, boy! You heard the question. You just don’t like the answer.” He paused just long enough to get a full chest of air. “I asked, ‘Have you ever served your country?’ The answer is, no, you have not. Have you ever killed another man? Huh? Have you ever taken another man’s life and then cashed the check your country gave you for doing it? No, you have not. So shut the fuck up!” I could feel his body pulsing with anger next to me. “You don’t know what the hell you are talking about!”

Kristofferson was a self-described “dove with claws,” who remained fiercely proud of his military service. Indeed, at least some of his backstage outburst at the Nelson show could have been rooted in a distant sense of recognition—he’d included a pro–Vietnam War song on his debut LP. But as he explained to Hawke, his view of the war reversed as he spoke with traumatized veterans:

I was flying helicopters in the Gulf of Mexico on one of those offshore oil rigs, and I was talking to some guys coming home. The stories they were telling me were so horrible that I think it just shocked me enough to change my thinking 180 degrees. I’m talking about things like this young vet telling me about taking people up in a helicopter and interrogating them and if they didn’t say what they were supposed to, they’d throw them out, stomping on the fingers of the prisoner holding on to the skids, you know? The guy telling me this particular story was still just a green kid when he returned from the war. The notion that you could make a young person do something so inhuman to another soldier—or even worse, a civilian—convinced me that we were in the wrong. I hadn’t been thinking in human terms of what that military action was.

That vital, hard-won understanding of the real costs of America’s imperial adventures stayed with Kristofferson throughout his life. In a 1991 interview on New Zealand TV as he toured with the Highwaymen supergroup, Kristofferson lit into the government-media nexus then touting the first US invasion of Iraq as a blow for freedom and a new democratic regional order: “The lapdog media cranks out propaganda that would make a Nazi blush,” he groused as his bemused bandmates looked on. He also did benefit concerts for Palestinian children, and saw his career suffer as a result: “I found a considerable lack of work after doing concerts for the Palestinian children,” he said. “And if that’s the way it has to be, that’s the way it has to be. If you support human rights, you gotta support them everywhere.”

Kristofferson’s principled political commitments might seem surprising for a songwriting legend in a steadily right-veering pop-culture genre. Yet his political views were of a fundamental piece with his closely observed, heartfelt writing. “Sunday Morning Coming Down” is such an effective country song because it doesn’t make good-times sport of a crushing hangover but instead plumbs its intimations of mortality—in much the same manner that the testimony of the vets he transported in the Gulf of Mexico started him thinking differently about war. “Well, I woke up Sunday morning with no way to hold my head that didn’t hurt,” the song begins, and its chorus builds on the same lost and despairing mood: “There’s nothing short of dying / That’s half as lonesome as the sound / Of a sleeping city sidewalk / And Sunday morning coming down.”

Kristofferson’s singular gift was to observe such mundane downfalls without sentimentality or fake machismo; the same can be said of his equally hard-won political views. In the end, the best line from “To Beat the Devil” serves as a fitting epitaph: “I ain’t saying I beat the Devil / But I drank his beer for nothing, and then I stole his song.”

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation