Blood, Guts, and Queer Bodybuilders

The Kristen Stewart–helmed erotic thriller Love Lies Bleeding filters a study of sex, violence, and the limits of human will through a romance that begins in a New Mexico gym.

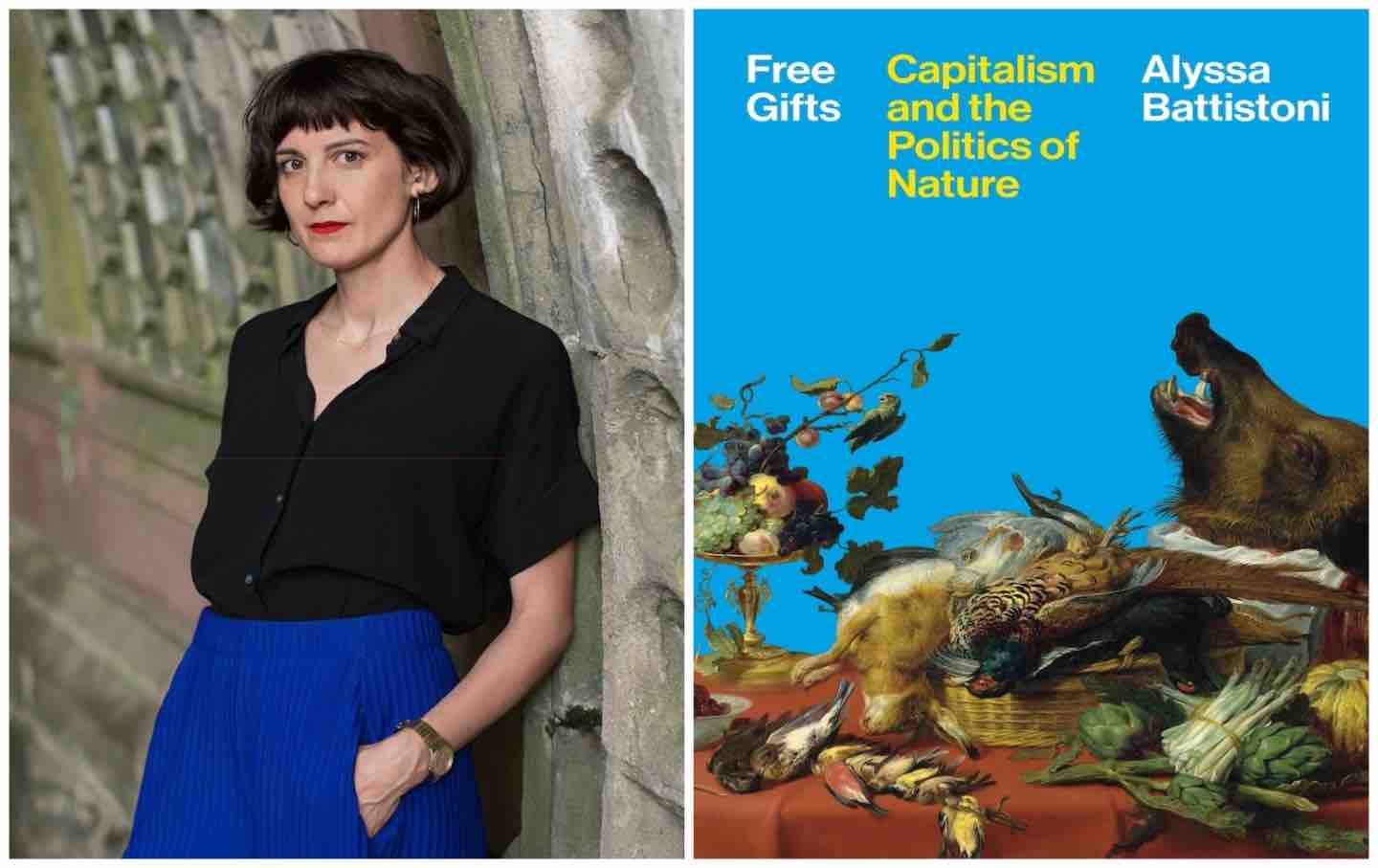

Katy O’Brian and Kristen Stewart

(Photo by Anna Kooris)“I’m in love with red. I dream in red,” read the opening lines of Kathy Acker’s My Mother: Demonology. Red is everywhere for the narrator: It’s the color of her nightmares, the tint of her passion, joy, and rage. In Rose Glass’s Love Lies Bleeding, Kristen Stewart’s Lou dreams in red, too. The film opens on her recurring vision: The camera hovers over the edge of a cliff that emits a menacing crimson glow, then plunges down to the bottom, a place shrouded in darkness. A lesbian neo-noir, Love Lies Bleeding takes red as its guiding light. The film’s women freak out and become furious; they spill blood and push their bodies to the edge. They love to death.

Love Lies Bleeding extends a torrid tradition of crime thrillers like Gun Crazy (1950) and Bonnie and Clyde (1968), with Bound (1996) as its sapphic forebear in this well-known genre of shoot-’em-ups and amour fou. Like those films, it’s a blood-and-guts-and-sex-soaked tale of two lovers who fend off gangsters, crooked cops, and evil fathers. Set in the American West circa 1989, the film puts a queer spin on the macho 1980s—the decade of hulking action stars like Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenneger; of cocaine and its promise of endless vigor; of Ronald Reagan and get-rich-or-die-trying materialism. This ethos of abundance applies instead here to the female body and soul—forces too strong and furious to be contained by the strictures of heteronormativity. This girl-power messaging simmers throughout, yet Glass’s script (cowritten with Weronika Tofilska) never stoops to the kind of rah-rah feminism that whittles characters down to pat symbols. It relies purely on intuitive forces, on surreal style and physical performance, to communicate its tale of feminine rebellion.

Early on, we’re welcomed to Cavern Gym, a spartan facility in the middle of a no-name border town in New Mexico. We hear the clang of weights, the whizzing of stationary bikes, the grunting and panting of sticky bodies captured in depersonalized close-up. Traditionally, fitness culture has tended to perpetuate a cis-hetero image of beefy men and lithe women; but here, the celebration of suffering and the body in extremis—“Pain is weakness leaving the body” reads one of the gym’s several motivational posters—has a primordial heft to it, one that hits beyond gender. Pain is universal; so is taking a dump. When we first spot Stewart’s Lou, a gangly butch and the manager of Cavern Gym, she’s unclogging a toilet choked up with someone’s gnarly bowel movement. Later, when she spots a muscular babe, Jackie (Katy M. O’Brian), getting hit on by a meathead, she immediately shuts off the lights, repelled by this open display of straight courtship and jealously protective of her new crush.

Lou’s got several chips on her shoulder: a mobster dad (Ed Harris), her namesake and the owner of a gun range and diner where Jackie gets a waitressing gig; her sister’s husband, J.J. (Dave Franco), a lowlife with a handlebar mustache, frizzy mullet, and penchant for domestic abuse. Lou’s sis, Beth (Jena Malone), a busted-up housewife with a blond bob, is her sole reason for sticking in town. Someone’s got to keep J.J. in check, and Lou, lanky though she is, has a bruiser’s disposition and a scowl that could scatter a crowd. Once complicit in Lou Sr.’s shady business dealings, she’s no stranger to whacking wiseguys, though the sardonic undertones in Stewart’s performance give the red-blooded proceedings some snark and levity. The actress has an authentic sort of swagger not unlike James Dean’s—her rugged cool and vulnerability are of a piece. In other words, for all her spacy reserve, she is one to fall in love.

Lou’s humdrum existence receives a sudden dose of adrenaline when the nomadic Jackie struts into town, intending to hang out and ramp up her training regimen before heading to Las Vegas the following month for a national bodybuilding competition. A parking lot meet-cute between the two women ends with Jackie slugging her snubbed male suitor (and receiving a black eye in exchange). Foreplay consists of Lou gifting Jackie with vials of steroids abandoned at the gym and injecting some into her derriere. Up till then, Jackie had been sculpting her body “au naturale,” but the thrill of instant gains is addictive for her—and so, too, are fresh love and sexual abandon.

The film pokes fun at the phenomenon of the U-Haul lesbian by following up the women’s first night of synth-scored cunnilingus with a morning-after in which Lou gives Jackie the OK to move in immediately with her. Incidentally, Lou has been trying to quit smoking. A self-help cassette tape tells her that withdrawal creates an “empty feeling” that she must restrain herself from filling—ironically, nothing about Love Lies Bleeding is suggestive of restraint. To its detriment, the film zooms through the couple’s honeymoon period, which both plays into the joke that lesbians move too fast and presumes the audience’s familiarity with lovers-on-the-run narratives (add to Bonnie and Clyde riffs like Badlands and True Romance) that run hot from the get-go. Stewart and O’Brian have a feisty rapport, which is scantly showcased in the film’s too few scenes of quiet lounging. The approach of competition day in Las Vegas matches the swiftness with which Lou and Jackie settle into their own brand of blissed-out domesticity in New Mexico, which Glass presents in a gauzy, suggestive montage of needles puncturing flesh and sizzling egg whites whose yolks have been tossed into bowls of cigarette ash.

Earlier in the film, Jackie expresses her lack of interest in guns despite her angling for the gun-range job—she prefers to “build her own strength,” she tells Lou Sr. The classics of crime-couple cinema usually like to fetishize the weapon: its phallic spurts of ammo and conferral of life-ending strength, which stokes delusions of grandeur that anticipate an eventual defeat. See, for instance, Gun Crazy, the prototype of the genre, which follows two lusty sharpshooters emboldened by their skills to commit bank robberies that yield an escalating number of casualties. Love Lies Bleeding employs a similar calculus, yet it triggers the genre’s snowball effect of swelling chaos and bloodspill by using the body as its tool of invincibility. O’Brian does a lot of the heavy lifting here: Throughout the film, the camera cuts to her muscles in close-up, her thick veins throbbing intimidatingly, suggesting a dark weapon whose full powers have yet to be unleashed. That the female body could be such an awesome, terrible weapon is the film’s greatest provocation.

With a background in law enforcement, competitive bodybuilding, and martial arts, O’Brian is a natural action star. The chiseled actress is exciting to look at even when she’s standing still, poised and preternaturally confident. Her “pretty serious lines” (as Lou calls them) beckon admiring gazes. There’s a feline twinkle in her eyes, edging on the feral, that complements the curves of her muscles, lending her look a playful femininity (her backless tank tops and Daisy Dukes also help), while her curly brunette locks recall the late Lisa Lyon, muse to Robert Mapplethorpe and the first winner of an international bodybuilding championship for women.

As Jackie gets increasingly jacked—as well as manic from the heavy influx of ’roids and good loving—she begins to see red as well. In the movies, when women “see red,”,they tend to be in the grip of a terrible spell, a psychosis: think Alfred Hitchcock’s Marnie or Quentin Tarantino’s Kill Bill. A few days before Vegas, J.J. puts Beth in the hospital, sending Lou into a rage that causes both her and Jackie to snap. Then the corpses begin to pile up. Effortlessly, Jackie breaks J.J.’s skull open with a few knocks against a coffee table; dutiful Lou cleans up the mess, dumping the body off that same wretched cliffside from her dreams.

The remainder of the film unfolds as a somewhat indifferent revenge plot that puts Lou Sr. under fire for J.J.’s death—Lou knows all too well that there are other bodies at the bottom of that pit. More captivating is Jackie’s spiral, its violent, visceral effects tripled by dint of her unique physical strength. Despite being told by Lou to lie low and stay home, Jackie is beset by competition-day tunnel vision that sends her hitchhiking to Vegas; there, she at first wows the judges, then loses it mid-pose. Glass shows Jackie’s breakdown as a procession of body-horror hallucinations in which she spits out a fetal version of Lou and imagines her competitors as cackling demons.

If the ensuing carnage feels mostly rote, Glass does manage to conjure a climactic image that brings together the film’s ideas about excess and power, gender and fantasy. In Jackie’s final showdown with Lou Sr., her muscles seem to burst out of her skin. But instead of transforming into a beast, she emerges as an evil-vanquishing giant, a literal tall-tale hero who effortlessly beats Lou Sr. into submission. In the next scene, we see Jackie and Lou—both magnificent superhumans running gleefully toward freedom against a shimmering backdrop of pastels. In My Mother: Demonology, Acker writes that when it came to plotting her escape from her parents and their rules, she thought she needed a man to do it; Bonnie needs Clyde to flee her lifeless town. Eventually, Acker realizes that linking up with a guy is a dead end. “My body was all I had,” she concludes. The women of Love Lies Bleeding have only their bodies, too—but that’s more than enough. Big and glorious, their bodies allow them to flee the scene of the crime, skip town, and forge their own escapes.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation