The Silencing of Sylvia Plath

In Emily Van Duyne’s Loving Sylvia Plath she asks if we can fully understand the poet’s work without understanding her abusive marriage to Ted Hughes.

A photograph of Sylvia Plath on her grave at St Thomas A. Beckett churchyard, Heptonstall, West Yorkshire, 2011.

(Amy T. Zielinski / Getty Images)

In the afterword to Loving Sylvia Plath, a book detailing the abuse that Plath suffered at the hands of her husband, the poet Ted Hughes, the literary scholar Emily Van Duyne recounts that when she started the book, a friend told her that she had to get “everything right” because “everyone is going to come for it.” Van Duyne took this to mean that the book had to be “textual,” not merely “rhetorical.” Getting “everything right” meant being sure to base her claims in verifiable, textual evidence and the documented historical record. There was good reason for the friend’s warning, its roots deep in the unsavory and litigious history of biographical publishing on Plath. Janet Malcolm depicted it as a field ruled by Hughes’s sister, Olwyn, who for decades was Plath’s literary executor, but who considered her a “nasty selfish bitch” (as Plath put it in a 1961 letter) and who granted access to the poet’s archive and permission to quote from her work only on condition of the biographer’s willingness to tell the story that the Hughes family wanted told.

Books in review

Loving Sylvia Plath: A Reclamation

Buy this bookThe friend’s sense that Van Duyne had to get “everything right” may also have been in reference to the combustible nature of her central claim: that Ted Hughes inflicted physical and emotional violence on Plath over the course of their six-year marriage. Van Duyne further claims that, after Hughes left her in the summer of 1962 for a woman named Assia Wevill, Plath strenuously tried to free herself from their abusive marriage, actively seeking a divorce and working to rebuild her life without him, though she struggled to rebound in part because she suddenly found herself a single mother. Plath was deeply concerned about how she would support her two young children while trying to maintain her professional life as a writer—all without consistent childcare. In Van Duyne’s portrait, the months before Plath’s 1963 suicide were indeed characterized by the return of her long battle with mental illness, but there’s also a sense that Plath was clearheaded about the monumental challenges that lay ahead of her as a single, working mother. “How can I ever get free?” she wrote in October 1962. “My writing is my one hope, and that income is so small. And with these colossal worries & responsibilities & no-one, no friend or relative, to advise or help as things come up, I have got to have a working ethic.”

This version of Plath clashes with the mythology surrounding her, which Van Duyne is at pains to show was constructed by Hughes and a cohort of powerful male critics and poets in the wake of her death. In their mythology—the one that has taken hold in popular culture—Plath was an unstable genius whose last burst of poetic productivity, the poems collected in Ariel (1965), drove her fully to madness. Her suicide, according to this myth, was foreordained, almost inevitable, and poetry was the cause. One of the original architects of this myth, the literary critic Al Alvarez, described Plath’s Ariel poems as “a murderous art,” and another, George Steiner, wrote that Plath “could not return from them.” In this story, Hughes is absolved of any wrongdoing.

Van Duyne’s sense that she must anchor her book in textual evidence may also stem from the fact that claims of intimate partner violence are systematically dismissed, silenced, or minimized in our patriarchal culture. In the parlance of the philosopher Kate Manne—whose theory of misogyny Van Duyne uses to understand how Plath’s claims of abuse have been overlooked and silenced—those who speak up about their abuse are routinely made to “eat their words.” Van Duyne, herself a survivor of intimate partner violence, fears that in making such claims about Plath, she too will be made to eat her words. So she insists on the text—the words that Sylvia Plath wrote and said. As it turns out, she said quite a lot.

In 2017, 14 letters written by Plath resurfaced. Since the 1970s, they’d been in the possession of Harriet Rosenstein, who wrote her dissertation on Plath and had set out to write what would have been one of the first biographies of her. By all accounts, Rosenstein was a prodigious researcher and interviewer. Van Duyne posits that many of the friends of Plath that Rosenstein interviewed considered her a proxy for Plath, and they eagerly offered their memories and assessments of the poet. One of these interviewees was Dr. Ruth Beuscher, Plath’s psychiatrist. Beuscher treated her at McLean Hospital after her suicide attempt in 1953 (which Plath fictionalized in The Bell Jar), and the two stayed close in the decade that followed: In 1958, she treated Plath again when she was in Boston for a year with Hughes, and in 1959, when Plath settled in London, she maintained a correspondence with her until Plath’s death in 1963. Beuscher gave Rosenstein these letters, but Rosenstein never finished her biography, and the letters resurfaced only when she attempted to sell them in 2017. Van Duyne makes the case that a small number of people likely read these letters in the 1970s, including Robin Morgan, the feminist activist and poet who openly accused Hughes of violence against Plath in a poem called “Arraignment” (a poem that was censored by Morgan’s publishers under the concern that it risked libel). But as the decades wore on and biography after biography of Plath appeared, the letters remained unseen. They became available to scholars just in time for Heather Clark to consult them as she finished her own biography of Plath, Red Comet, which was published in 2020 and nominated for the Pulitzer Prize the following year.

The letters matter for several reasons. For Plath scholars, one reason is that they cover a period, from 1960 to 1963, for which there is comparatively little archival material. Plath wrote prolifically over the course of her short life; her journals and letters alone number in the thousands of pages. But Ted Hughes burned one of her last journals and claimed to have lost another. The letters suggest some of what may have been contained in those last journals. They are a devastating record of the great hope that Plath had for her young family and her career, and starting in July 1962, a gutting account of her marriage’s disintegration and the intensification of her mental illness.

They matter, too, because they make a straightforward claim of Hughes’s physical abuse: “Ted beat me up physically a couple of days before my miscarriage,” Plath wrote to Beuscher in a letter dated September 22, 1962. Plath had miscarried in February 1961. She’d discussed the miscarriage in an earlier letter to Beuscher as well, from March 1962, where she wrote, “I lost the baby that was supposed to be born on Ted’s birthday [last] summer at 4 months…. No apparent reason to miscarry, but I had my appendix out 3 weeks later, so tend to relate the two.” These statements, and the apparent contradiction between them, have received much attention, not least from Plath and Hughes’s daughter, Frieda Hughes, who now holds her mother’s copyright (Ted Hughes’s second wife, Carol Hughes, holds his). Frieda Hughes did not know of the existence of the Plath-Beuscher letters, let alone their contents, until 2016. Since that time, she has allowed them to be published with the rest of Plath’s known correspondence in the second volume of Letters of Sylvia Plath.

In her foreword to the volume, published in 2018, Frieda Hughes writes movingly of reading these letters for the first time, and she asks readers, first and foremost, to consider them, including the statement of physical violence, in “context.” Context, she writes, “is vital.” To supply this context, Frieda Hughes offers a portrait of her parents’ marriage as unsustainable from the beginning: two artists in the grips of a great passion, who spent almost no time apart for six years, a relationship that had no “oxygen.” She asks readers to remember that Plath wrote that line—“Ted beat me up physically”—in the midst of great pain at learning of her husband’s infidelity and suggests that it would make sense that Plath, in that moment, would want to paint Hughes in the “darkest colours.” The other important context, to Frieda Hughes, is Plath’s provocation of her father. In the letter to Beuscher, Plath writes that Hughes beat her after she had torn up some of his writings—she was furious that he was late to take over the care of Frieda so that Plath could go to work at one of her part-time jobs. Placing the statement in this context, Frieda Hughes comes to see that her father was not the “wife-beater that some wish to imagine he was.”

Heather Clark also calls attention to the fact that Plath follows her claim about the abuse by writing, “I thought this an aberration.” In her discussion of the event and Plath’s 1962 letter, Clark writes: “Whatever happened between Sylvia and Ted that day, it was unusual enough that both poets singled it out as…an ‘aberration,’ in their marriage…. According to Sylvia’s September 1962 letter to Beuscher, nothing like it ever happened again.”

To understand these lines of Plath’s—which Clark, I believe, has misread—we need even more context, more text on the table. We need to consider the entire paragraph in which they appear—that is to say, Plath’s whole thought. The line “Ted beat me up physically a couple days before my miscarriage” appears in the middle of a paragraph that is primarily about Hughes’s relationship to their son, Nicholas, who was about 8 months old at the time of Plath’s letter. After opening it by saying that she is going to London to see a lawyer about a legal separation, and telling Beuscher that Hughes’s weekly visits to their house make her “miserable,” Plath abruptly writes: “He hates Nicholas.” She then relays a story of Hughes forgetting (or perhaps refusing) to buckle Nicholas into his stroller, even after Plath had reminded him to do so. She writes that Hughes “did not even go pick him up” when he tumbled out of the stroller onto the concrete floor; “the cleaning lady did that.” She then says that Hughes “has never touched [Nicholas] since he was born, says he is ugly and a usurper.” Plath clarifies to Beuscher that Nicholas is, in fact, a “handsome vigorous child” and immediately follows this with the line about the abuse, which is important to quote at length:

Ted beat me up physically a couple of days before my miscarriage: the baby I lost was due to be born on his birthday. I thought this an aberration, & felt I had given him some cause, I had torn some of his papers in half, so they could be taped together, not lost, in a fury that he made me a couple hours late to work at one of the several jobs I’ve had to eke out our income when things got tight—he was to mind Frieda. But now I feel the role of father terrifies him. He tells me now it was weakness that made him unable to tell me he did not want children, and that his joyous planning with me of the names of our next two was out of cowardice as well. Well bloody hell, I’ve got twenty years to take the responsibility of that cowardice.

Seeing the whole paragraph, it becomes clear that what Plath is thinking about here is Hughes’s relationship to fatherhood—how it “terrifie[d] him.” This is what the paragraph is about. Its purpose is not to announce the news of having had a miscarriage (Plath had already told Beuscher that fact six months earlier) or even the abuse itself. The purpose is to illustrate Hughes’s fear of fatherhood, his “hatred” of the male child, and his violent reactions against both. Her purpose, in other words, is not merely to narrate the event but to interpret it anew: She has just begun to see Hughes’s actions, including the moment of physical abuse before her miscarriage, as connected to his antipathy to the very idea of being a family man. To Plath, her pregnant body became one target of this antipathy.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Plath’s use of the word “aberration” should also be tied to this new understanding. When Plath writes, “I thought this an aberration…. But now I feel the role of father terrifies him,” the key word here is “but.” What Plath seems to be expressing is that she had originally thought this moment was an aberration, but now she sees many of Hughes’s actions—not buckling Nicholas into the stroller, beating her when she was pregnant, being late to take over childcare duties—as consistent, not aberrational, with never truly wanting children. Plath is not using the word “aberration” in reference to a pattern of violence against her, as Clark suggests. The pattern she is tracking in this paragraph is Hughes’s animosity toward having a family; the event fits right into this newly gleaned pattern. To be clear, then, when Plath says, “I thought this an aberration,” we cannot take it as hard evidence, as Clark seems to, that Hughes beat her only this one time.

As though once wouldn’t have been enough to make Van Duyne’s case. For her, the unveiling in 2017 of Plath’s statement merely confirmed with fact what Van Duyne and other Plath scholars had long sensed to be the case. “It was only possible to be shocked by Plath’s accusations of abuse if you had ignored or disbelieved her—or, importantly, people writing about her—for the last fifty-one years,” Van Duyne writes. For while there are no other known statements in the Plath archive as direct as “Ted beat me up physically,” Van Duyne shows that there’s plenty more evidence of violence coursing through it. She brings to the foreground an episode from the couple’s honeymoon—when Hughes strangled Plath on a Benidorm hillside—that has swirled around the biographical treatments of both Plath and Hughes. Plath seems to have told the story to her close friend Clarissa Roche in November 1962. Roche, in turn, acting as a confidential source, told the story to the Plath biographer Paul Alexander, who published an account of it in his 1991 biography, Rough Magic. Van Duyne also points to a number of poems in which Plath uses strangulation imagery, including “The Rabbit Catcher.” But many of the big names writing about the Plath-Hughes fray have dismissed or minimized the story: Jonathan Bate, a Hughes biographer, cast the moment as embedded in and inseparable from a sexual encounter and called it, in any case, “unverified,” while Janet Malcom excoriated the account presented in Alexander’s book—a book she “profoundly dislike[d]”—writing that its aim seems to have been to “see how outrageously it can slander Hughes and still somehow stay within the limits of libel law.”

As much as Van Duyne’s book seeks to provide textual evidence of Hughes’s violence (and does), it’s this tendency—the tendency not to take Plath at her word, and to make her eat her words—that Van Duyne especially illuminates. It is structural to patriarchy that survivors’ narratives are disbelieved, or that the narrators themselves are subject to moral interrogation. The result is epistemic injustice (in the words of Miranda Fricker, upon whom Van Duyne draws): an act of even further violence that silences testimony, rendering it almost inaudible, such that a person can say the words “Ted beat me up physically” or even dramatize such violence in poetry (see, for instance, Plath’s poem “The Jailer”), and these words can fly right by—so much so that a whole book must be written to argue that what Plath said happened, happened.

Painfully, in the culture of misogyny, sometimes even reams of textual evidence aren’t enough to counter a myth. When Van Duyne’s friend tells her that she has to get “everything right,” Van Duyne’s first instinct is to stick to the text—but upon further reflection, she writes, the evidence for her discoveries about Plath transcends the text. Instead, it is embodied, felt. “I could not have written [this book] without the embodied experience of loving Sylvia Plath—tramping across graveyards and into the British Library, standing alone on a dark March night outside the London home where Plath killed herself, trying to leave, and feeling, each time I turned to go, that something called me back.” Her discoveries are also gleaned in the light of her own experience of intimate partner violence, which Van Duyne relayed in series of propulsive essays for Literary Hub, weaving together the story of her escape from an abusive partnership—how she fled at dawn with her infant son—with her revelations of Plath’s abuse. Van Duyne’s lived experiences create an identification with Plath that, far from undermining Van Duyne’s credibility, as she worries it will, convinces the reader of her ability to recognize in Plath what she, too, once suffered. Her work reveals the scholarly power of identification, or experience as a lens—what she calls the “communion of women who know what [Plath] went through.”

Women, perhaps, like Assia Wevill, the woman of Ted Hughes’s affair. In 1969, six years after Plath’s death by suicide in her London apartment, Wevill died in the same manner: suicide by gas in her London home. She also intentionally killed the child she had with Hughes, the 4-year-old Shura Wevill. Van Duyne writes that bringing Wevill’s story into her book makes Plath’s experience look less “anomalous” and more like a “larger pattern.” It also, for me, brings motherhood to the very front. Reading the Plath-Beuscher letters and Van Duyne’s Loving Sylvia Plath, my lens of experience is being the mother of two very young children—one, a boy, of nearly identical age to Nicholas when Plath died, and the other, a girl, the same age as Shura at the time of her death. I reflexively flinch when I read “Ted beat me up physically,” but I break when I read the letters to Beuscher as a series that begins with Plath telling her psychiatrist the story of Frieda’s birth (“I had the baby completely without analgesia of any sort”) and writing in its aftermath, “I don’t know when I’ve been so happy.” Her hopes grow—“I’m still nursing her, which pleases me very much: it’s been one of the happiest experiences of my life. I didn’t know what I was missing, really, in not having children, & now only look forward to buying a house big enough to hold as many as we want”—before they come crashing down, with Plath frantically searching for childcare so she can carve out time to write after Hughes leaves her. My baby was very recently 6 months old, Nicholas’s age when Hughes left Plath, such a tender, overwhelming time. When I look at pictures of Shura, I can only weep.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Best Albums of 2025 The Best Albums of 2025

From Mavis Staples to the Kronos Quartet—these are our music critic’s favorite works from this year.

Forrest Gander’s Desert Phenomenology Forrest Gander’s Desert Phenomenology

His poems bridge the gap between nature’s wild expanse and the private space of one’s imagination.

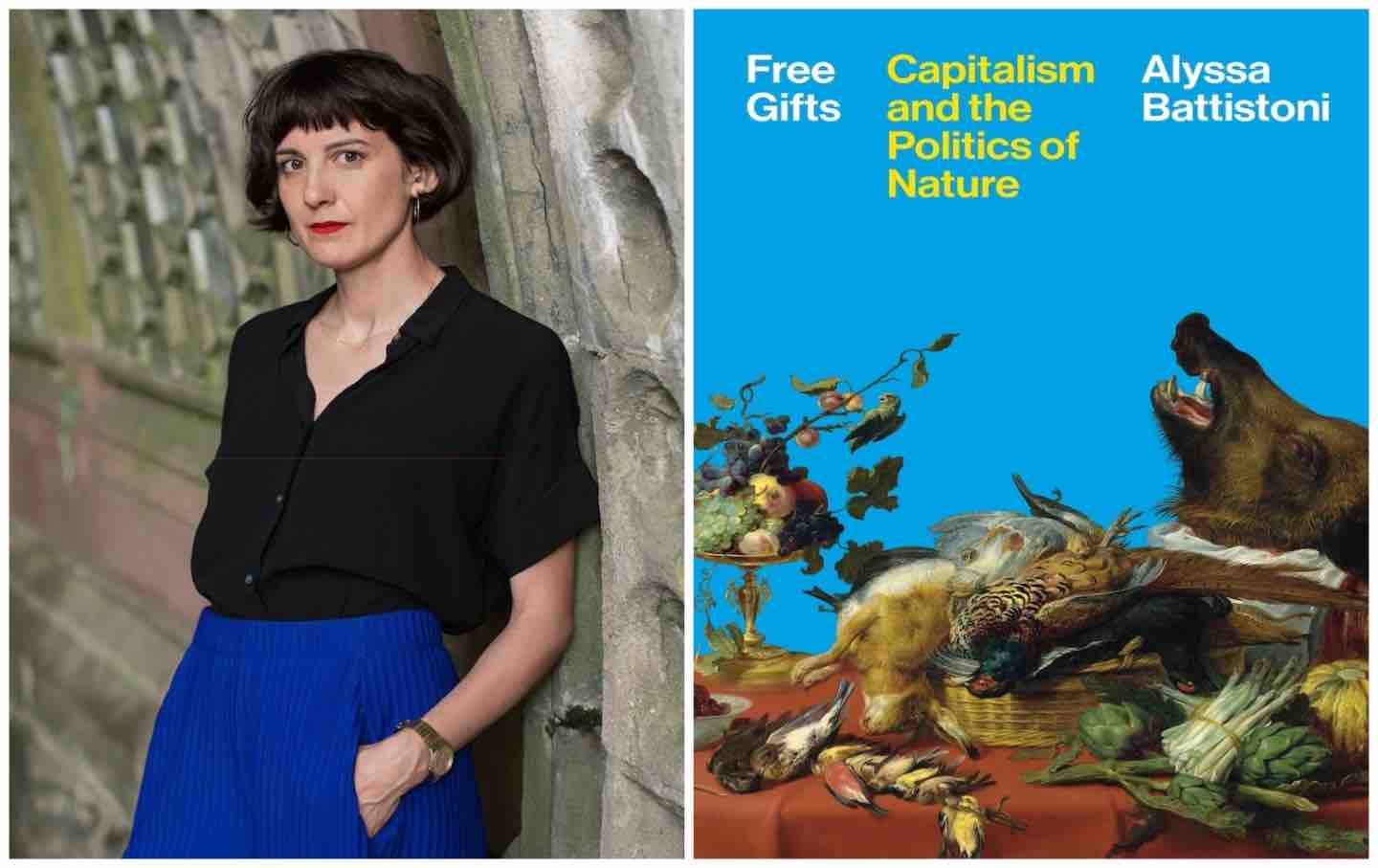

Capitalism’s Toxic Nature Capitalism’s Toxic Nature

A conversation with Alyssa Battistoni about the essential and contradictory nature of capitalism to the environment and her new book Free Gifts: Capitalism and the Politics of Nat...

Solvej Balle and the Tyranny of Time Solvej Balle and the Tyranny of Time

The Danish novelist’s septology, On the Calculation of Volume, asks what fiction can explore when you remove one of its key characteristics—the idea of time itself.

Muriel Spark’s Magnetic Pull Muriel Spark’s Magnetic Pull

What made the Scottish novelist’s antic novels so appealing?

Luigi Pirandello’s Broken Men Luigi Pirandello’s Broken Men

The Nobel Prize-winning writer was once seen as Italy’s great man of letters. Why was he forgotten?