Metaperson

The enchanted worlds of Marshall Sahlins

The Enchanted Worlds of Marshall Sahlins

What if we saw the study of ghosts, gods, and other metapersons as worthy of a science of its own?

Is a god, or any divine power, only a mirage of the human-made political structures that oppress us? This understanding of religion, popularized by 19th-century thinkers like Karl Marx and Émile Durkheim, has become received wisdom among the anthropologists and sociologists studying the origins and functions of religious life. We sense that we live under forces of authority that constrain us, and yet we cannot precisely locate or understand them. Needing to give some shape or form to this coercion, we project it onto the clouds, fashioning heavenly beings that are ultimately deifications of the human state. “Religion is realistic,” Durkheim noted; it corresponds to our social realities and reinforces them.

Yet the existence of societies without chiefs or kings, or any vertical political organization, challenges this picture. In communities that traditionally recognized no rulers or government, from Tierra del Fuego to the Central Arctic to the Philippines, we still find complex concepts of celestial hierarchies, metahuman authorities, and bureaucracies of deities and spirits with no correspondence to the human social order. Where do these ideas come from, which reflect no living conditions on the ground? How is it that notions of the state seem to be anticipated by cosmology before they are realized in society?

These questions lie at the heart of Marshall Sahlins’s final book, The New Science of the Enchanted Universe: An Anthropology of Most of Humanity. Across most cultures, Sahlins observes, human life unfolds in continuous reference to other beings—supreme gods and minor deities, ancestral spirits, demons, indwelling souls in animals and plants—who act as the intimate, everyday agents of human success or ruin, whether in agriculture, hunting, procreation, or politics. These not-quite humans, or metapersons, can be found across all landscapes, from the Chewong “leaf people” in the Malay Peninsula to the Greenland Inuits, who had the idea that spirits animate each human joint and knuckle. Indigenous communities possess empirical knowledge about these spirit worlds, yet anthropologists often use the language of “belief”—or worse, “folk belief”—to describe them, an approach loaded with their own disbelief. Rejecting the obscurant category of “belief,” Sahlins asks: What if we saw metapersons as worthy of a science of their own? If we examine them as a ubiquitous global presence, and attempt to tease out general theories about their role in human political and economic life, what would this new science teach us?

Published posthumously, The New Science of the Enchanted Universe is riveting, and this is in part because Sahlins writes with an incantatory, late-style openness to the existence of metapersons—just as he began to turn into an ancestral spirit himself. In the late autumn of 2020, Sahlins had become paralyzed after a fall; not long before his 90th birthday, he slipped into a dissociative state and was given days to live. Yet he soon surfaced from the hereafter, determined to finish the manuscript. Having lost the use of both hands, over the next few months he dictated it to his son, the historian Peter Sahlins, and completed it a month before his death. The book (“my swan song,” as he calls it in the preface) is electrified by ideas—of human finitude and eternity, the interlacing of the political, the enchanted, and the divine—that Sahlins, even near his end, could not lay to rest.

If Marshall Sahlins had a faith of his own, it was humor. Born in 1930 in Chicago, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants, Sahlins was raised in a secular household, although his family counted among its ancestors the 18th-century Jewish mystic Ba’al Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidic Judaism, who was famous for his laughter during a Passover seder. This contagious, charismatic wit was something of a family inheritance—his brother Bernard Sahlins later became a comedian, while Marshall became known for a mix of mischief and polemic that ignited conversations as well as the written page. He studied anthropology at the University of Michigan, sailed through a PhD at Columbia in two years, and then returned to Michigan to teach.

In those years, Sahlins was an evolutionary materialist, interested in how cultures evolve alongside technological progress. His dissertation, Social Stratification in Polynesia, took this approach, looking at how cultural difference arises through environmental and economic factors. Yet by the mid-1960s, the United States’ disastrous war in Vietnam had shattered the technological determinism that Sahlins was taught in school and revealed to him how ways of understanding cultural progress are often at the behest of empire. As Sahlins recalled in an interview, he became interested in what he called “the indigenization of modernity,” the ways in which peoples attempt “to engage the encroaching ‘World System’ in something even more encompassing—their own system of the world.” He had observed this phenomenon during fieldwork on the island of Moala in Fiji in 1955, when he studied how chiefly lineages adapted to new orders of power.

The 1960s were a transformative period for Sahlins, intensifying his left-leaning commitments and sharpening his political activism. Amid the upheavals in the United States and Vietnam, Sahlins detected “a clear and simple law of revolution”: that it is the rulers, not the revolutionaries, who undermine a society’s culture and principles of government. “It is from deep traditional values that the opposition draws its outrage—and in defense of them, takes to the streets,” he later reflected in a collection of political essays, Culture in Practice. At an all-night protest in Ann Arbor in 1965, Sahlins led the first anti–Vietnam War “teach-in” and is often credited as the inventor of the concept, which took college campuses by storm. Soon after, he organized a national teach-in of thousands of students in Washington, D.C., and the following year he flew to Vietnam, where he taped a set of darkly absurd dialogues with American operatives—“hard-headed surrealists,” as he called them.

In 1968, Sahlins moved to Paris to participate in the famed anthropological laboratoire of Claude Lévi-Strauss, and he also witnessed the mass student protests and workers’ strikes that year. Inspired by the collective uprising, he sought to adapt Lévi-Strauss’s theory of structuralism, of how symbols, patterns, and binaries form the building blocks and hidden laws that structure human thought. What happens when these structures collide with a revolutionary present? How do individuals become agents of historical change? Amid the labor strikes, Sahlins was also contemplating how leisurely life must have been in the Paleolithic period. In his essay “The Original Affluent Society,” he argued that hunter-gatherers lived not in hardscrabble misery, on the edge of starvation, but in prosperity.

“There is,” Sahlins wrote, “a Zen road to affluence, departing from premises somewhat different from our own: that human material wants are finite and few.” Among pre-agricultural tribes, Sahlins calculated, food acquisition took only three to five hours per day, leaving plenty of time for feasting, recreation, and sleep. In contrast, “the market-industrial system institutes scarcity, in a manner completely unparalleled,” as it requires insufficiency as the foundation of all economic activity. Poverty, Sahlins wrote, is above all “a relation between people. Poverty is a social status. As such, it is the invention of civilization,” which forges tributary relationships between classes. Sahlins developed these ideas in Stone Age Economics (1972), a book that, half a century later, remains a prophetic call for degrowth amid the current climate collapse.

For Sahlins, Indigenous cultures offered profound counterpoints for how humans might live, a theme he continued to develop after his move in 1973 to the University of Chicago, where he remained for nearly 50 years. In Islands of History, he began to investigate how divinity intersects with cultural structures and historic events—most notoriously through the fate of James Cook. In 1779, when Captain Cook landed on Hawaii, he was reportedly hailed as the god Lono, and a rapturous crowd of thousands offered him sacrifices. Yet when Cook stepped ashore a second time, after his ship was damaged in a storm, he was slain; Sahlins argued that this was because Cook was inadvertently playing out the script of a myth held by the islanders that when the god returns, he must act out a battle with the king. To the anthropologist Gananath Obeyesekere, Sahlins’s analysis was exoticizing and patronizing, for it denied Hawaiians common sense: Why would Polynesians mistake a Yorkshireman for their own god? For Obeyesekere, what he called “practical rationality” was universal, while Sahlins argued for its cultural specificity in his 1995 book-length reply, How “Natives” Think (About Captain Cook, for Example). On Hawaii, Sahlins wrote, “politics appears as the continuation of cosmogonic war by other means.”

These ideas deepened through Sahlins’s ongoing dialogue with a luminous former student, the author and activist David Graeber, who died less than a year before his teacher. In 2017, Sahlins and Graeber published the monumental On Kings, in which they argued that the structures of sacred kingship have never vanished from modern politics or our institutions of “popular” sovereignty. Throughout On Kings, supra-human beings continuously appear, ever setting “the terms and conditions of human existence.” One even appears on its cover: the frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan, depicting the crowned monarch rising above the human landscape, his body made of myriad tiny persons who blur together like a scaly coat of armor. The image reveals how metapersons have penetrated the conceptualization of the state in Western traditions often deemed the apex of rational, secular thought. The essence of political power, Sahlins and Graeber wrote, “is the ability to act as if one were a god; to step outside the confines of the human, and return to rain favor, or destruction.” It must have been while he was writing On Kings that the metapersons approached Sahlins and requested, or demanded, that he devote an entire book to them.

The New Science of the Enchanted Universe takes as its starting point perhaps the earliest cultural revolution, that of the “Axial Age,” the period between the eighth and third centuries BCE in which the civilizations of Greece, the Near East, India, and China underwent a seismic shift. Notions of divinity, Sahlins tells us, moved “from an immanent presence in human activity to a transcendental ‘other world’ of its own reality,” creating the foundations for the Vedic, Buddhist, Judaic, and (later) Christian and Islamic religions. In the disenchanting exodus of transcendence, the high gods and spirits evacuated to the upper echelons of the sky, “leaving the earth alone to humans, now free to create their own institutions by their own means and lights.” In societies that remained enchanted, the legions of metapersons continued to be “the decisive agents of human weal and woe,” and what we would call “culture” was still not considered “a human thing.” In contrast, in the transcendental societies, culture became humankind’s own invention, a domain entirely under our control.

In what Sahlins calls the “Second Axial Age,” rooted in the doctrinal wars and imperialist conquests of the early modern period from the 15th through the 19th centuries, European civilization forged a set of abstract, differentiated spheres—“religion,” “politics,” “economics,” “culture,” “science,” and “nature”—that created further distance from the once-enchanted cosmos. The realm of the economy came to be seen as the base of the pyramid of quotidian life, while divinity moved from being the infrastructure to the superstructure. With each axial turn came a host of intractable theological dilemmas; throughout the book, the immanentist perspective emerges as the most intuitive, as it escapes the perennial problem of theodicy—of why an infinitely benevolent Almighty would cause so much harm to mortals, or even get involved in their minutiae—that plagues transcendentalism.

In The New Science, Sahlins attempts to convene a vivid conference of metapersons and let them speak, without imposing the distorting transcendentalist categories upon them. These familiar binaries—of “natural” versus “supernatural,” “material” versus “spiritual,” “secular” versus “religious”—make no sense, he argues, as a way to understand the halibut master of species that brokers deals with Kwakiutl fishermen in the Pacific Northwest. For ancient Sumerians, minerals like salt were alive, with opinions of their own. BaKongo people had a practice of shaving the head to keep it clear and smooth “for spirits that might want to land there,” as the anthropologist Wyatt MacGaffey reported. It is not surprising, given the huge range of ways to suffer, that demons tend to be the most diverse and heavily populated class of metahumans: The Chewong recognize 27 different types. “All that exists lives,” a Siberian Chukchee shaman told the Russian ethnographer Waldemar Bogoras. “The lamp walks around. The walls of the house have voices of their own…. Even the shadows on the wall constitute definite tribes and have their own country, where they live in huts and subsist by hunting.”

The Chukchee, descended from nomadic hunter-gatherers, are among what Sahlins calls the “so-called tribes without rulers” who historically lacked vertical political structures yet knew entrenched cosmic forms of authority. In the early 20th century, the shaman described to Bogoras how they were subjugated to hosts of invisible, mercenary spirits with whom they had to forge alliances or pay ransoms for protection. One might theorize that cosmic polities are modeled, if not around earthly political coercion, then after patriarchy within the unit of the human family itself. Yet even in communities that prize familial relationships of equality, Sahlins notes, such as the Buid of Mindoro in the Philippines, we find strongly hierarchical concepts of the metahuman world that in no way reflect their equitable mode of life. Sahlins particularly focuses on geographically isolated groups uninfluenced by transcendentalist missionaries, such as the subarctic Naskapi in what is now northern Canada, who acquiesce to no authority except the overlord Moose-Fly. Flanked by his avatars, the stinging moose-flies that appear during the summer salmon-fishing season, Moose-Fly rules over the fish tribes upon whom Naskapi life depends. Humans must obey his laws, such as never making fun of a fish for its big eyes.

“The state of nature had the nature of the state,” as Sahlins put it in a companion essay in the volume Sacred Kingship in World History (2022). If immanence was the original human condition out of which transcendentalist civilizations arose, it follows that a hierarchical cosmology was already in place from the beginning—almost as if originating from a source that preexisted human life. This possibility is furthered by the existence of utterly random, bizarre laws that seem to serve no human function (the United States has many). In The New Science, Sahlins compares the Inuit “rules of life” recorded in Baffin Land in the 1920s—“If a woman sees a whale, she must point to it with her middle finger”—to an ancient Akkadian list of commandments, including that one must never point at a lamp. Even where there is no clear moral content, what is at stake is obedience to the higher metapersonal powers, in a deference “even better served by ‘irrationality,’” a pattern replicated in the whims of autocrats today. If “power descends from heaven to earth,” Sahlins writes, “human political power is necessarily and quintessentially hubris, the appropriation of divinity in one form or another.” The charisma of politicians is always given by the gods, such as the mana handed down to legions of Melanesian chiefs. In his essay, Sahlins touches upon the interesting point that hubris, or overstepping the boundaries between the human and the divine, also underlies structures of class, with elites often seen as possessing or appropriating spirit-power. In turn, any emancipatory movement must mobilize the metahuman as “the necessary precedent of political action.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Sahlins has an eye for profound, poetic details and writes with a deep empathy, as someone who is constantly moved by the ideas and worldviews he encounters. Yet his project is tricky, as he still can’t help but fall back on the transcendental language of culture, politics, and science that he is familiar with to communicate what he wants to say. There is also always the anthropological danger of heroizing such traditions in a way that reduces their complexities. At times, The New Science risks falling into the same trap as the debate with Obeyesekere did, of the attempt to unearth what people really think (or worse, believe), for one will never truly know. One might ask not only why ideas of the metapersons are so lasting and compelling but also why the anthropological impulse to take them “on their own terms,” even if this is impossible, endures. It remains a powerful mode of political self-critique—and a kind of self-help, much needed—of which Sahlins is a master, although it ultimately speaks more to “the West” than anyplace else, confronting it with other ways to live and face death.

In between roving from the Amazon to New Guinea, Sahlins might have opened the door of his study to the many contemporary American metapersons, from extraterrestrials and angels to imaginary friends in childhood. Even in any allegedly disenchanted culture, the vestiges of the immanent never disappear. We continue to live in a world crowded with nonhuman persons, from commercial brands who speak in distinct “voices” on Twitter, to currencies with their own agency, to the meat shunned by vegans, as Sahlins observes, on the premise of “the personhood of food.”

Along with demons, ancestral spirits—including the “recent familial dead”—are an especially populous global demographic. Sahlins writes beautifully of traditions in which the dead are kept close at hand. In Kwaio settlements in the Solomon Islands, he relates, people spoke as frequently to their dead relatives as to their living ones. During a festival period in the Trobriand Islands off New Guinea, when the baloma, or ancestral souls, are said to return, the deceased are so closely present that the living must be careful not to spill hot drinks or wave sticks in the air, lest they injure the spirits. “‘Lineage’ as the participation of the ancestor in the bodies and identities of living persons—as by the transmission of ‘blood,’ ‘bone,’ or ‘soul’—is a spiritual condition,” Sahlins writes. He might also have explored the American ritual of transmitting samples by mail—to corporations such as Ancestry.com and 23andMe—as a way to find lost ancestors and locate ourselves in the still-enchanted webs of human kinship. For “humans are spirits too,” Sahlins reminds us.

When the academic reviews of The New Science of the Enchanted Universe began to appear, following its publication a year after Sahlins’s death, I noticed a strange phenomenon: For a genre conventionally prosaic, the scholarly critics kept having encounters with the metaperson of Sahlins himself. When Katherine Pratt Ewing, a professor of Islam at Columbia University, sat down to write her review at her dining table on a Sunday morning, she suddenly found herself slipping into “an almost hypnagogic state in which Marshall was a felt presence,” she recalled in HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory. “It wasn’t a matter of belief about whether this was possible—it just was.” Ewing later realized that Sahlins had appeared to her on the morning of his memorial service, held at the University of Chicago on April 3, 2022.

“I kept trying to imagine how he would take my comments,” the anthropologist Carlos Fausto wrote in another piece for HAU. “Would he act like a benevolent or a mean-spirited ancestor?” Ancestors, Sahlins had wryly observed, are ambivalent powers, usually the most moralistic of all metahuman types. They are needy, even though “they are not actually in need of anything,” to quote the Swiss ethnographer Henri Junod. At the memorial service, Sahlins’s former doctoral student Sean Dowdy gave a eulogy, and he was certain—for a moment—that he saw Sahlins sitting in the crowd, carrying himself with a shabby dignity. Dowdy spoke of how the late professor had been appearing to him in dreams. In one, Dowdy walked up the stairs to Sahlins’s house on University Avenue. Sahlins opened the door wearing his usual navy-blue sweater vest, greeted Dowdy with a smile, and asked him how the mourning had been going.

It seemed to me that Sahlins, ever since his death, was continuing to develop the arguments of The New Science in a new way. (The book was meant to be a trilogy, if only Sahlins had more time.) The scholar Frederick B. Henry Jr., another former student and longtime friend, worked tirelessly to prepare the manuscript for publication. Henry told me how, as he was driving down a highway in Princeton to an early morning appointment, he suddenly realized that Marshall was sitting in the passenger seat. He stayed there for 10 minutes, as Henry’s hair stood on end and a wave of joy and sadness overcame him. “I found myself belly-laughing at some unidentifiable joke he had manifested beside me to deliver,” Henry recalled. Sahlins was inimitably demonstrating his point, of the immediacy of the spirit world that ever surrounds us. “It is the flip-side, behind the mirror of our limited being,” Henry wrote to me. “None of it need be considered paranormal in the slightest. It is part and parcel of our human condition…. I will eventually become a metaperson, to someone. So will you.”

More from The Nation

“The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy “The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy

The new show from the creators of The Office reminds us that their comedic style does now work in every “workplace in the world.”

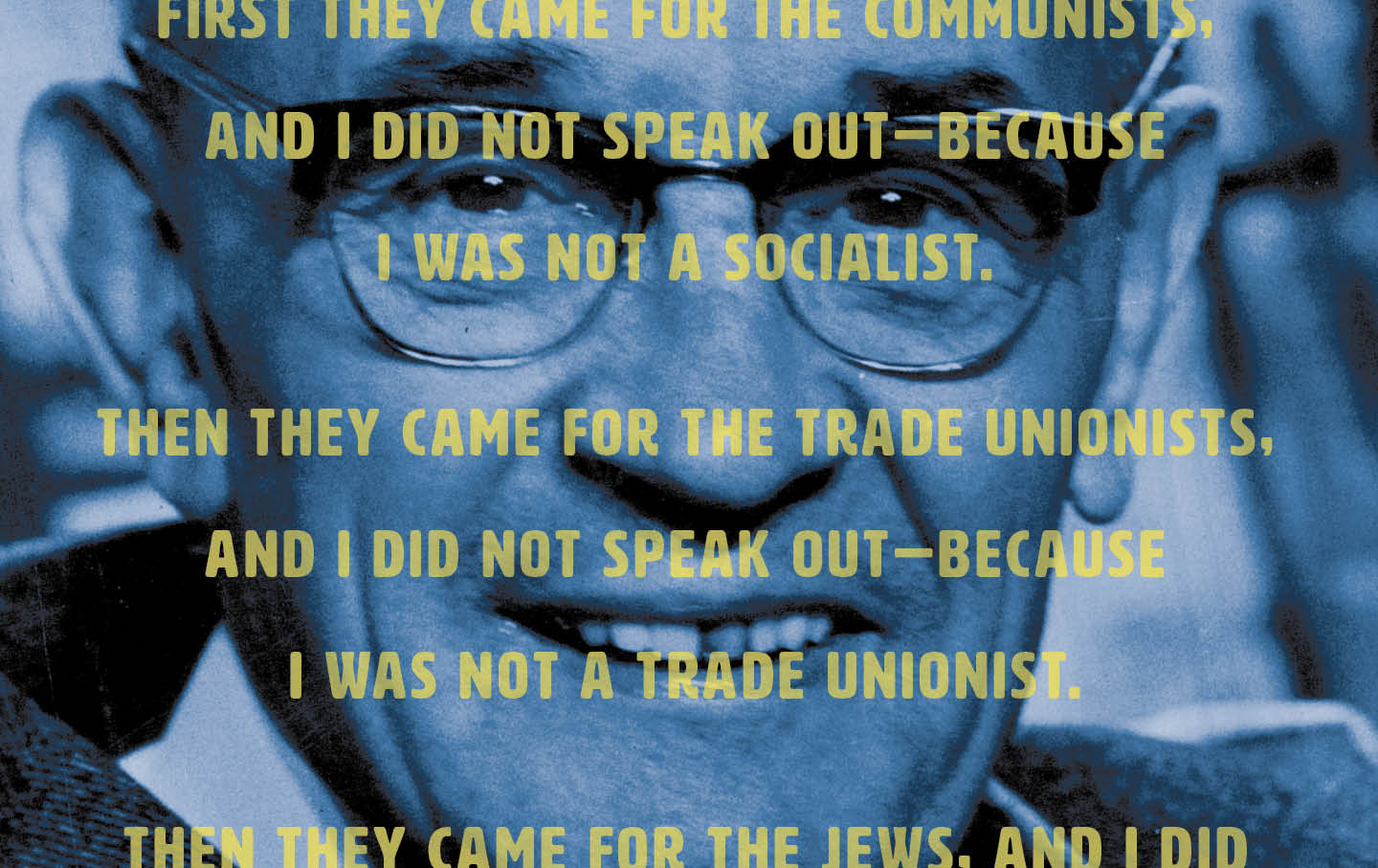

The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…” The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…”

In his celebrated mea culpa, the German pastor Martin Niemöller blamed his failure to speak out against the Nazis on indifference. Was that the whole reason?

John Updike, Letter Writer John Updike, Letter Writer

A brilliant prose stylist, confident, amiable, and wonderfully lucid when talking about other people’s problems, Updike rarely confessed or confronted his own.

The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme” The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme”

Josh Safdie’s first solo effort, an antic sports movie, revels in a darker side of the American dream.

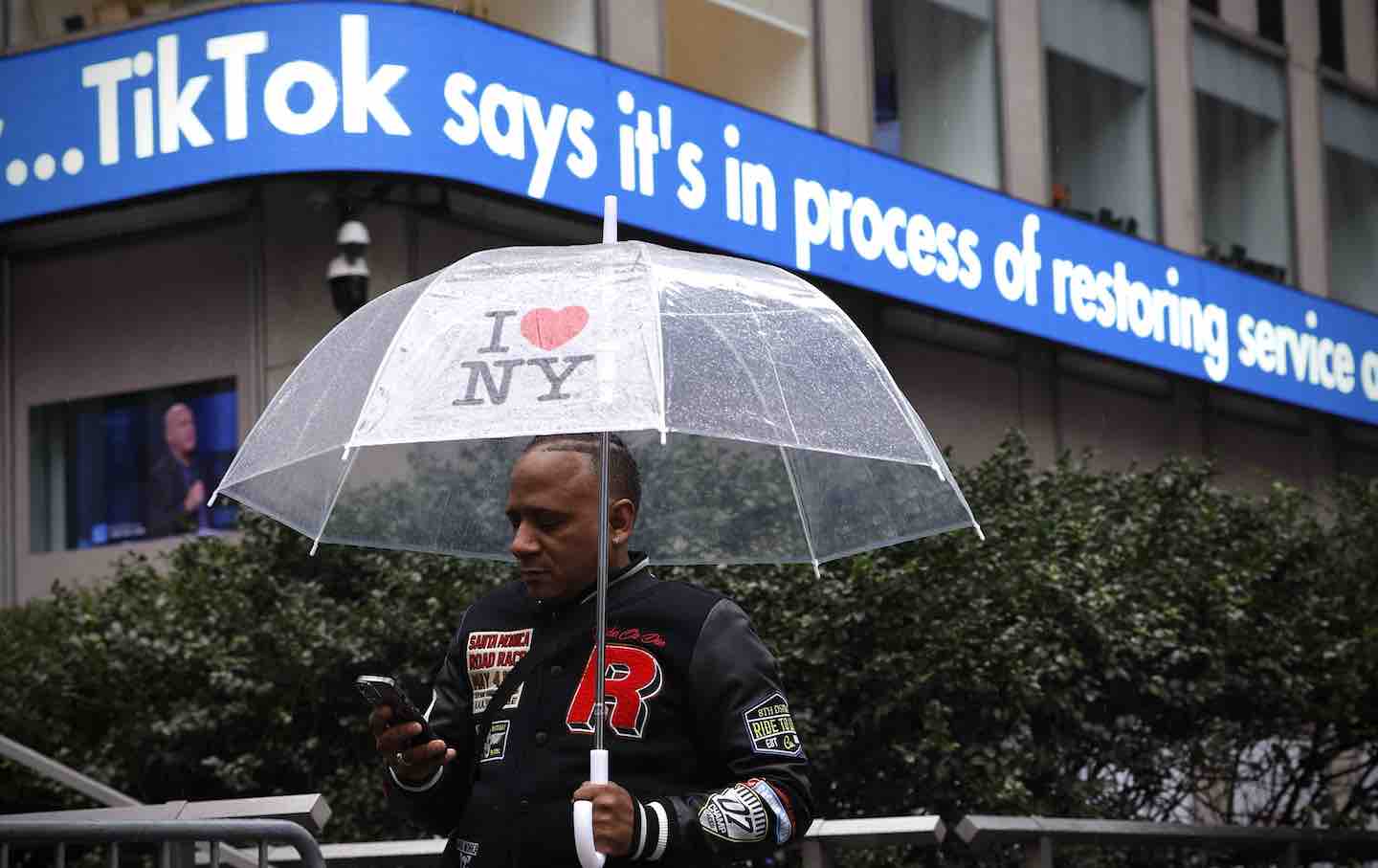

TikTok’s Incomplete Story TikTok’s Incomplete Story

The company has transformed the very nature of social media, and in the process it has mutated as well—from tech unicorn to geopolitical chesspiece.