Friends and Enemies

Marty Peretz and the travails of American liberalism.

Marty Peretz and the Travails of American Liberalism

From his New Left days to his neoliberalism and embrace of interventionism, The Controversialist is a portrait of his own political trajectory and that of American liberalism too.

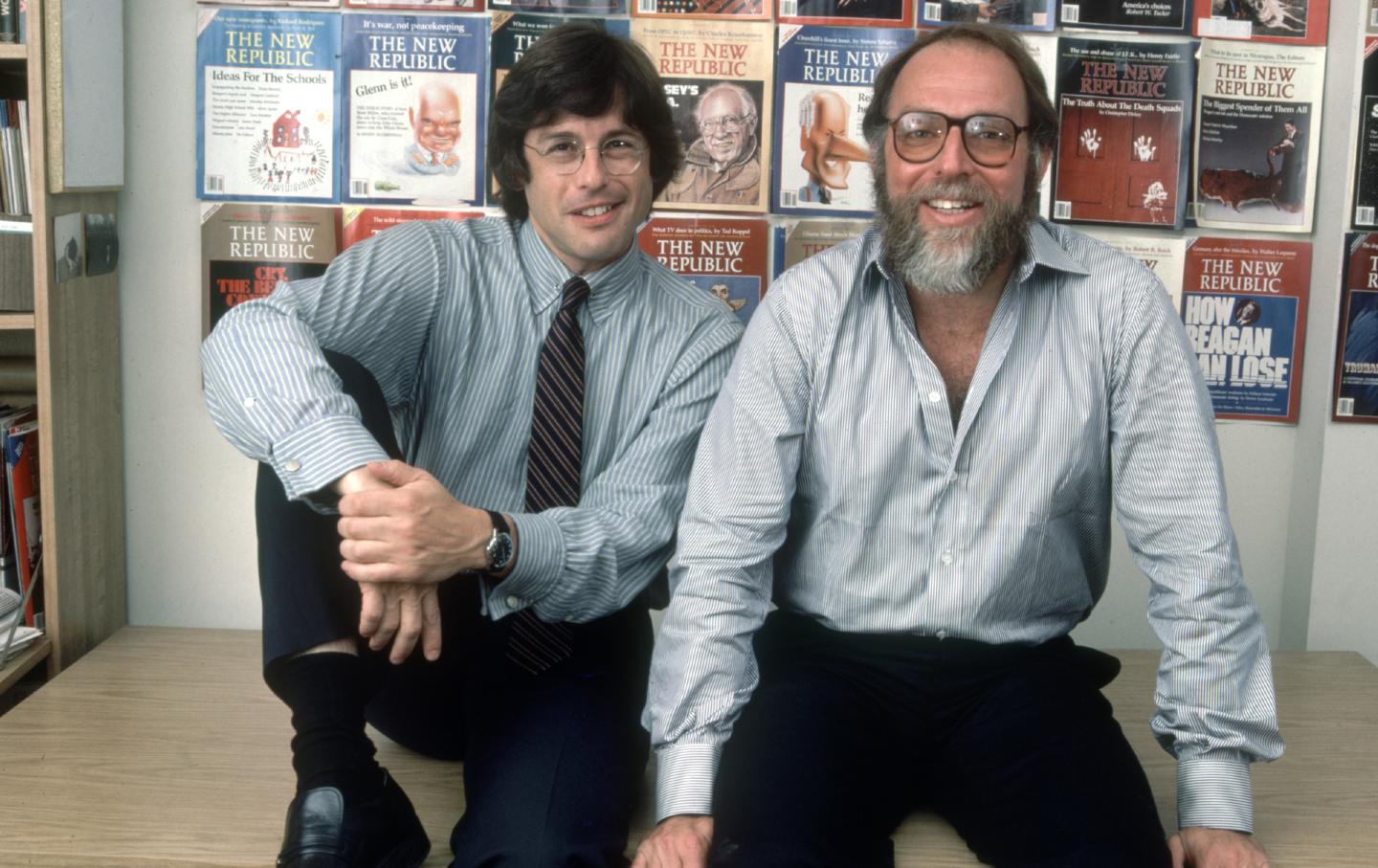

Martin Peretz (R) and then–New Republic editor Hendrick Hertzberg, 1984.

(Cynthia Johnson / Getty)In 1975, Susan Sontag—the star intellectual of her generation—was forced to confront the fact that she was just another American without healthcare. At 42, she made a rare visit to the doctor, which brought the terrifying news of a tumor in her left breast. The metastasized cancer had already reached Stage 4. She soon underwent a radical mastectomy, which left her feeling “maimed,” and girded herself for an even more ruthless remedy: an experimental course of immunotherapy developed by a Parisian oncologist.

As a freelance writer whose books enjoyed more prestige than sales, Sontag didn’t have any health insurance. The treatment would cost $150,000 (or more than $850,000 in 2024 terms). Fortunately for Sontag, she did have access to an alternative in the United States to a welfare state: extravagantly wealthy friends. Spearheading the campaign to fund Sontag’s treatment were her publisher, Roger Straus, and her editor at The New York Review of Books, Robert Silvers. Straus, a Guggenheim heir, and Silvers, a lifelong partner to Grace, Countess of Dudley, were perfectly positioned for the delicate job of passing around the hat to those with plump bank accounts.

Among the many people the pair approached was a couple who had the requisite combination of cultural aspirations and a superabundance of ready cash: Anne and Marty Peretz. Anne, a left-leaning philanthropist and heir to the Singer sewing machine fortune, and Marty, then the owner-editor of The New Republic, decided to pitch in. As Marty recalled, “After a little discussion, Anne and I said yes, even though we felt strange giving money to someone we didn’t really know who had very rich friends. If I tell myself the entire truth, I might have been pleased to be asked: it felt like I was being let into the cultured inner sanctum.”

That Marty Peretz, a consummate outsider, would actually be invited in was another matter. When Sontag later had dinner with the Peretzes, she wasn’t all that nice. Chilly to Marty, she condescendingly told Anne, “You are a very good homemaker.” Marty was “startled”—the couple didn’t exactly expect thanks for their help, but they assumed that “good manners” and “common decency” might mean that Sontag would at least treat them as her equals.

The dinner with Sontag is recounted in Marty Peretz’s memoir, The Controversialist, in which the polarizing publisher recounts the many friends and equally numerous foes he has encountered in a roller-coaster life that has seen him move from the periphery of American society to the centers of power only to then find himself a near-pariah late in life in the communities where he once ruled the roost. In The Controversialist, Peretz recounts his ups and downs with a certain knowingness that can be, at times, candid or evasive, boastful or apologetic. Peretz tells his story in the irascible, self-pitying, blunt voice of an octogenarian gearing up for the Seinfeld-ian ritual of Festivus, where he can shout out all his grievances. Beginning with his hothouse upbringing in an argumentative and often abusive household in the Bronx in the 1940s, and continuing with his emergence as a wealthy supporter of radical causes during the heady 1960s and his political U-turn toward neoliberal disillusionment in the last quarter of the 20th century, The Controversialist offers a portrait not just of Peretz’s own ideological and social trajectory but also of the long shadow he cast over American political culture as one of the most pivotal liberal figures in the second half of the 20th century. For better and (often) for worse, Peretz has been a force in American life for decades, and his story is not just of one man but of a politics, and an elite, that has never quite been able to come to terms with its culpability for triggering the ever-widening crises of the 21st century.

Born in 1938, Martin Herbert Peretz grew up in the Bronx. He didn’t come from poverty; his father was a landlord who rented property in Washington Heights and owned a pocketbook factory. But he did grow up in a world touched by the poverty of others—a claustrophobic, Yiddish-speaking and Shoah-haunted immigrant milieu far from the American mainstream. The most emotionally hard-hitting pages of The Controversialist, in fact, come from those moments when he talks about this often isolated and traumatized world: the helpless anguish and guilt his parents and the parents of his peers felt as they followed the horrifying news of the Nazi slaughter in Europe, knowing full well that many of their closest kin were being killed. As Peretz recalls, “My father had nine brothers and sisters and, aside from my uncle Jake, who lived in Brooklyn with his wife and owned a candy store, they and their families were all in Europe. My parents had a list of the people who they were close to, and they were always waiting for them to write. Most of them never did.”

From this shell-shocked and marginalized beginning, Peretz pursued a swift path of upward mobility via higher education. Entering Brandeis University—then a haven of radical intellectuals—in 1955, Peretz found himself in an entirely new world: In Waltham, Massachusetts, he met C. Wright Mills, Irving Howe, and Herbert Marcuse. More than Mills and Howe, Marcuse was an especially important mentor to Peretz, who took from the abstruse German refugee the lesson that “sex—real sex, exploratory sex, sex sundered from consumer corruption—was the key to political liberation.”

More from Books & the Arts

This is, of course, a simplification of the kinds of lessons that Marcuse was hoping to teach his young American students, but it also speaks to Peretz’s early attraction to the burgeoning New Left, and in particular the ways in which it combined political and sexual liberation, a radical activism and counterculture. Indeed, sexual liberation emerges as an important—albeit oblique—theme in Peretz’s memoir, where for the first time he publicly identifies himself as gay.

After graduating from Brandeis, Peretz stepped up the academic ladder and embarked on a PhD in government at Harvard. He fell in love with the storied university almost as soon as he arrived, becoming a self-professed “Harvard patriot” who cherished the institution for sociological as well as academic reasons. It was there, after all, that he could both engage in brainy talk with figures like Stanley Hoffmann and Erik Erikson and also, as he knew from the start, meet a new generation of elites. For Peretz, Harvard was a second Ellis Island, where the offspring of recently landed immigrants could mingle with the old-money Brahmins.

With the New Left starting to coalesce, Harvard was also a place where a politically minded academic could help tutor this new elite in a more enlightened and radical politics. With his friend Michael Walzer, who made the same journey from Brandeis, Peretz became the academic mentor to undergraduates forming civil rights and anti-war groups. He carved out an anomalous position at Harvard. Senior scholars, such as Judith Shklar, quickly sized him up as someone lacking a scholarly bent and discouraged him from pursuing an academic career. But he proved to be a popular teacher at Harvard and served as an assistant professor and lecturer for five decades. Peretz became, as he notes, a “fixture” at the university, a mentor to many students who would go on to major achievements, from the future Tennessee senator and vice president Al Gore on down.

If Peretz did not often find that he was his fancy professors’ favorite pupil, his fledgling career as a New Left organizer and Harvard guru was helped by a different source of encouragement: In 1962, he married a wealthy heiress named Linda Heller. She gets only two skimpy paragraphs in his memoir, but it is hard not to assume that Peretz’s marriage to Heller helped secure a kind of social cachet that had thus far eluded him. The Heller family were Florida citrus growers, with tendrils stretching from Fifth Avenue to Miami Beach; once Peretz had joined this chic and moneyed family, he was able to throw lavish parties filled with professors, intellectuals, writers, aspiring politicians, and more than a few celebrities.

It was before this first marriage, while Peretz was making a name for himself as a rising young man who was both debonair and politically radical, that he also met Anne Devereux (Labouisse) Farnsworth. Six years later, she became his second wife—and if Heller had given him a leg up, then Farnsworth did even more. Born in 1938, Anne grew up in a world of almost unimaginable wealth, with family members owning entire city blocks of prime New York real estate as well as paintings by Matisse, Picasso, and van Gogh. Her grandfather Stephen Clark, whose own grandfather had helped start the Singer Sewing Machine Company, bequeathed her a painting that he knew she liked because she had written a term paper about it. It was a Rembrandt. At one point, the family also owned 39 Renoirs.

Family opulence on that scale is invariably rooted in brutal primitive accumulation. The Singer company had a history of union-busting and a soul-crushing enforcement of “scientific management” designed to turn workers into efficient cogs. As a student at Smith, Anne sought to make amends: She threw in her lot (and her purse) with the New Left and the fight for civil rights and peace. When she met Marty, the pair found in their commitments a shared interest; after both divorced their first spouses, they married in 1967.

To marry one heiress is proof of great good luck; to marry two heiresses suggests a calculating turn of mind. Disarmingly candid about many matters, Peretz is evasive on the questions raised by his marriages. But even while being close-lipped on this and other personal subjects, he becomes positively giddy at times when describing the enormous size of his second wife’s assets: Anne’s family, he tells readers, was “wealthy almost beyond imagining” and “astoundingly, alienatingly rich.” She felt like money “came from nowhere and kept raining down on her.”

Peretz had an idea of what she—and now he—might do with this endless downpour. The pair would spend their money on many causes. Along with the anti-war and civil rights movements, the couple had grown appalled by the civil war in Nigeria and organized the American Committee to Keep Biafra Alive. As Peretz recalls, “Anne and I were increasingly involved in Left causes: we bought a full-page ad in the New York Times with I.F. Stone’s essay against the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, and we supported Ramparts, a radical magazine.” In 1968, the Peretzes were also the single biggest donors to Senator Eugene McCarthy’s insurgent presidential campaign.

But even as the Peretzes became closely identified with an ascendant generation of the left, they also began to grow apart from it—or at least Marty did. In 1967, the couple financed the National Conference for New Politics, in Chicago, designed to bring together New Left and Black radical organizations into an umbrella group that would recruit Martin Luther King Jr. and Benjamin Spock to run a third-party anti-war presidential campaign. But the New Politics conference dissolved into a fury of bitter factionalism. It also started Peretz on his journey to the political right; in a very real sense, he never recovered from the hurt and anger of that moment.

In 1974, Peretz’s growing discontent with the left found a new outlet—a famous and well-reputed magazine. The New Republic, long an avatar of liberalism, had become something of an anachronism in a country torn apart by the battles over the Vietnam War and Watergate. The magazine’s owner, Gilbert Harrison, put it up for sale, and Marty, using Anne’s fortune, purchased it. Having promised to keep Harrison on as editor and retain the staff, Peretz reneged on that promise within the first 10 months of finalizing the deal, ousting not just Harrison but many staffers and replacing them with editors and writers who shared his goal of remaking liberalism. While still nominally a venue for Democratic Party liberalism, The New Republic over the next two decades would move ever more to the right, rejecting both the New Deal and the New Left and calling for a tougher liberalism that embraced welfare cuts, military intervention, and a two-fisted, negotiation-adverse Zionism. In some ways, this new incarnation of The New Republic marked a revival of the truculent early postwar days of Cold War liberalism, but it also proved much harsher toward the poor and less respectful of international law and diplomacy.

This policy mix of more money for weapons and less money for the poor paralleled the emerging neoconservatism that Irving Kristol and Norman Podhoretz had pioneered, but with two crucial differences: The New Republic continued to embrace a moderate social liberalism (becoming an early advocate in the United States for marriage equality), and it continued to support the Democrats (by 1980, most neocons had shifted their allegiance to the Republican Party). Even so, The New Republic promoted right-wing causes with a swagger and élan lacking in the conservative journals of that era, winning fans among people like Podhoretz and George Will. (The Reagan White House also had eager TNR readers.) The magazine also won over many parts of the Democratic Party’s center and right wings, which were also beginning to question and eventually reject the social democratic liberalism of the 1930s to ’60s.

The New Republic’s influence was reinforced by a remarkable social network that Peretz built and fused three nodes of American power in the 1970s and ’80s: Harvard, Washington, and Wall Street. While TNR was based in Washington and made inroads pushing national Democrats toward neoliberalism, Marty and Anne remained in Cambridge, where he continued to teach popular courses on political and social thought. At Harvard, Peretz was an anomalous big man on campus who hobnobbed with the university’s presidents and top tenured faculty and did much of the magazine’s talent-scouting there. While some of his students entered into politics—Al Gore, Antony Blinken, Merrick Garland—others, notably Michael Kinsley and Nicholas Lemann, became prominent journalists.

Most of Peretz’s acolytes, it turned out, were political in one way or another, but there was a third contingent too of avid capitalists who ended up on Wall Street: notably Jim Cramer, Lloyd Blankfein, and Bill Ackman. From the 1960s onward, Peretz also played the market, which put him in the thick of a world of hedge funds and junk bonds. Eventually, he entered into business partnerships with figures such as Ivan Boesky, Michael Milken, and Michael Steinhardt. Harvard provided the brains, Washington the power, and Wall Street the money. For a few decades, this system of interlocking elites worked for Peretz, making him a genuine power player.

The Democratic Party was also embracing this trio of often overlapping movers and shakers—the ambitious products of an elite university who became politicians and journalists, a Washington turning its back on the New Deal and the Great Society, and a Wall Street avariciously taking advantage of the new era of deregulation and social-spending austerity. As these different groups merged to become the dominant faction in the Democratic Party, it also began to shift, like The New Republic, ever more to the right as a new generation of “Third Way” candidates emerged, including Bill Clinton (praised by Peretz for being “friendly to finance”), Al Gore (Peretz’s former student at Harvard, who was wise to the need to be “incrementalist”), and Joe Lieberman (whose ridiculous presidential run was endorsed by TNR in 2004). As Peretz enthuses, this new crop of neoliberal Democrats “were willing to listen to Republican critiques of the welfare state” and “were not hostile to the increasingly powerful corporate sector.”

This new rightward turn in the Democratic Party was often outpaced by an even more rightward turn at The New Republic, leading to some the magazine’s most notorious positions. In February 1994, TNR unleashed right-wing pundit Betsy McCaughey, a denizen of the Manhattan Institute, on the Clinton administration’s healthcare reform plan. McCaughey claimed that it would forbid patients from privately paying for doctors, which The New York Times denounced as one of her “fearmongering falsehoods.” The most devastating debunking of McCaughey’s article also appeared in The New Republic, written by Mickey Kaus. But it ran a full 15 months after the offending article, and by then the damage had been done: McCaughey’s claims ended up widely amplified by right-wing pundits like George Will and Rush Limbaugh. Printing a lie as the main story in one issue and then tardily following up with the truth more than a year later is a good way to spread the lie.

Another moment of infamy came when The New Republic published an excerpt from The Bell Curve, the book by Charles Murray and Richard Herrnstein, which argued that Black people were genetically disposed to be intellectually inferior. “The point was to open a discussion,” Peretz claims. “I was happy to publish dissents” to the article. But that wasn’t the article’s effect; once again, the magazine gave its imprimatur to a fraud. The Bell Curve purported to be a work of science but was in fact pushed by a marketing strategy designed by the American Enterprise Institute, another right-wing think tank, to make a splash while evading scientific scrutiny. The book wasn’t peer-reviewed, nor were advance copies sent to the relevant journals. As The Wall Street Journal reported at the time, The Bell Curve was “swept forward by a strategy that provided book galleys to likely supporters while withholding them from likely critics.” And while The New Republic ran more than a dozen responses in the same issue, it included only one from an expert in the field of intelligence research. TNR’s coverage created the impression that the book was a work of scholarship that some liberal journalists might quibble with and that was open to debate, but that should still be taken seriously. This was not true: The Bell Curve was attacked by scholars, in specialized journals with circulations far smaller than TNR’s, who vigorously debunked it. Peretz and editor Andrew Sullivan had rigged the game for The Bell Curve to win. Peretz now admits that his goal was to get reluctant liberals to read a book they were inclined to disregard. In other words, he was part of the deceptive marketing strategy.

Embracing a politics of public selfishness, Peretz was nonetheless often bountiful in his personal dealings—the Sontag story was only one of many. Among the other beneficiaries of his charity was Henry Fairlie, a perpetually down-and-out TNR staff writer whose heart surgery was also paid for by the Peretzes. And yet all the while the public positions that Peretz and The New Republic advocated at the turn of the 21st century were the very opposite of munificence: Time and again, they advocated for a stingy and winnowed-down welfare state, expanded policing, and a militaristic foreign policy. Their motto could have been “More guns, less butter.”

You might think there’s a contradiction between being a Santa to your friends and a Scrooge to society. But in terms of pure class interest, private generosity and public selfishness aren’t really contradictory; they are mutually reinforcing. The well-to-do require low taxes and security of property (more police, more soldiers) so they can have funds to look after the needs of the special poorer people they have a fondness for. William Blake might have been thinking of Peretz when he wrote in Songs of Innocence and Experience: “Pity would be no more / If we did not make somebody Poor.”

But Peretz’s public stinginess and private beneficence were also ideological. Peretzian liberalism was committed to the idea that economic inequality wasn’t a social problem—poverty was no longer something that society had a duty to address; it was a regrettable condition to be ameliorated, if at all, on a personal level at the whim of the wealthy. One of TNR’s more intelligent writers in the Peretz era, Mickey Kaus, even wrote a book, The End of Equality, in 1992 outlining this vision: Liberals should give up the hope of economic equality (including their support for labor unions, the welfare state, and redistribution) and focus on fostering civic cohesion. Peretz and Kaus might have thought this was a hard-nosed liberalism. But, in truth, it was really an ideology of plutocracy.

Framed in these terms, Peretz is just another wealthy reactionary. After all, a mix of private generosity and public miserliness can also be said to be the politics of people like the late William F. Buckley Jr., as well as of the conservative mega-donors Charles Koch and Harlan Crow. They all have a record of extravagant charitable donation combined with support for public policies that entrench their class in power.

Yet, although he certainly shares many of their policy preferences, Peretz doesn’t quite belong in the camp of purely reactionary plutocrats. He doesn’t have the smugness of the breed, the Panglossian confidence that we’re living in the best of all possible worlds. He isn’t entirely blind to the iniquities of capitalism—and this remains true even in his memoir, many decades after his turn to the right. Because of his upbringing, and perhaps also because of his time on the left in the 1960s, Peretz can’t quite see himself as one of life’s naturally ordained winners. Even once he had “made it,” he still always felt like something of an arriviste and an outsider.

In this way, The Controversialist is the work of a profoundly unhappy man who realizes late in life that something has gone deeply wrong with his politics and with the world he’d hoped to create. With his home base at Harvard and his sway in Washington and on Wall Street, Peretz had hoped to “humanize the technocracy.” Yet the end result, as his book documents, is that he played his own modest part in the production of a ruling class that has become ever more intellectually crass, culturally philistine, morally callous, and self-interested. Here and there, Peretz has flashes of awareness that he played a role in helping to create these problems. In fact, the melancholy and unease of the book—and the occasional moments of painful recognition—redeem it from being merely an exercise in self-exculpation and score-settling (although both of those are present, too).

In this way, The Controversialist is actually shot through with a soul sickness. Peretz admits, “I am a dissatisfied man.” He laments that the United States has become “media-ized, financialized, and atomized.” His discontents are crystalized in what he describes as the most painful episode of his public life. The year is 2010. The Committee on Degrees in Social Studies at Harvard was marking its 50th anniversary with the creation of a fellowship in Peretz’s honor, for which $700,000 had been raised. Then Nicholas Kristof wrote a column in The New York Times calling attention to Peretz’s history of racism, including a TNR blog post in which Peretz opined that “frankly, Muslim life is cheap, most notably to Muslims,” and further wondered “whether I need honor these people and pretend that they are worthy of the privileges of the First Amendment which I have in my gut the sense that they will abuse.”

Peretz would later offer a half-hearted non-apology apology. But a storm of opposition was also brewing. Here’s Peretz’s account of the scene:

[T]he invasion of Iraq, which I backed, is a disaster; the financial system that my friends helped build has crashed; my wife and I are divorced; the New Republic is sold after I feared going bust—and here I am in my white suit walking across Harvard Yard, surrounded by students: “Harvard, Harvard, shame on you, honoring a racist fool.” The racist fool is, apparently, me. It’s a sodden coda, one I don’t quite grasp, or believe.

This moment shows Peretz squinting at the world he helped to create and also destroy. By then, he had lost much of his family’s money in reckless speculative investment—he played the market, initially with success, but ultimately it ended badly. The 2003 invasion of Iraq caused another divide in Peretz’s household. His wife opposed the war, but he dismissed her objections because “Anne was a peacenik from a long way back.”

On shaky financial footing, Peretz had to sell The New Republic in 2007 to a shifting series of owners–starting with the moguls Roger Hertog and Michael Steinhardt in 2001 and then the Canadian media conglomerate Canwest in 2007, then in 2009 it fell into the hands of a group of investors headed by the businessman Laurence Grafstein, and then finally in 2012 Chris Hughes who bought a majority share. In 2009, Marty and Anne got divorced. According to The New York Times, Anne’s grounds for divorce were his “infidelities and explosive temper.” She later remarried. Peretz still continues to wear his wedding ring.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Even while there are compelling moments in The Controversialist in which Peretz gives an admirably frank account of the foibles of the ruling class he joined, there are many in which his self-justifications and blinkered view of his own motives make it a text that demands critique rather than assent. The book is perhaps best read as one of the liveliest novels narrated by an unreliable narrator since Nabokov’s Lolita. Peretz’s vitriolic racism, which he waves away in The Controversialist as simply some moments of ill-advised blogging, is hard to ignore, and it follows from his larger post-welfare-state liberalism that turned its back on the midcentury left’s quest to link economic and racial egalitarianism.

Peretz’s lifelong and persistent bigotry is an outgrowth of his vision of an orderly society where the rich form a beneficent ruling class basking in the gratitude of the lower orders. The problem with Black Americans and the impoverished and working classes of America, and with Arabs in the Middle East, is that they don’t know their proper station in the world. These groups are ingrates asking for more than is their deserved lot. Speaking to Haaretz in 1982 during Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, Peretz recommended that Israel inflict “a lasting military defeat that will clarify to the Palestinians living in the West Bank that their struggle for an independent state has suffered a setback of many years. [Then the] Palestinians will be turned into just another crushed nation, like the Kurds or the Afghans.” Alas, the Palestinians—like the Kurds and the Afghans, as it happens—refuse to accept that their permanent destiny is to be a “crushed nation.”

Black Americans and Arabs are intertwined in Peretz’s racist imagination. Since 1967, he has feared that the Black freedom struggle in the United States will make common cause with Palestinian nationalism, and he has used the same language of cultural incapacity to insist that Black Americans learn their place in the world. Speaking at a conference on Black-Jewish relations in 1994 he said, “So many people in the black population are afflicted by deficiencies—and I mean cultural deficiencies—which Jews, for example, didn’t [have].” Asked to elucidate, he replied, “In the ghetto, mothers—a lot of mothers don’t appreciate the importance of schooling,” and added, “A mother who is on crack is in no position to help her children get through school.” (A 1996 TNR issue with an editorial advocating welfare reform featured a photo on the cover of a Black mother smoking.) He also stated, “It seems to me that a population 67 percent of whose children are born into single-parent families is a population which in large number is culturally deficient.”

Again, society and the larger social, political, and economic structures that might create a world riven by inequality are of little interest to Peretz. But his invocations of crack use and its detriments to Black America highlight not only a bad politics but also a double standard. When it comes to crime, Peretz believes in prison for the (often non-white) poor but pardons for his friends. Leon Wieseltier, Peretz’s consigliere and The New Republic’s literary editor from 1983 to 2014, was for a period an avid snorter of cocaine, selling books sent to him to consider for review for cash to pay for his quick hits. Another friend, Eric Breindel, suffered from heroin addiction. With his large and loving heart, Peretz never called either culturally deficient and was admirably steadfast in helping these friends in their darkest moments. He has also been notably loyal when it comes to more than a few of his business associates and friends who have turned out to be crooks of one sort or another. As mentioned earlier, his business partners have included Ivan Boesky (convicted of insider trading), Michael Milken (convicted of securities fraud), and Michael Steinhardt (made to surrender $70 million in stolen relics and barred from trading in antiquities), and there was also his friend (and unindicted war criminal) Henry Kissinger. But this is because the personal and the political are not connected for Peretz: For his friends he offers charity and succor, but for the great mass of society nothing but lectures on austerity and belt-tightening.

Peretz expected a similar loyalty in return. Rare was it that one of his friends or editors would say anything about his contradictions—let alone his racism and public parsimoniousness. For his book Sound and Fury, Eric Alterman asked TNR editor Michael Kinsley what he objected to most about the magazine. Kinsley responded, “I have a problem with some of the needlessly vicious things about Arabs that we publish.” A problem. Some. Needlessly. What a hero.

How do we weigh so large and various a legacy as that of Martin Peretz? We should be grateful that he helped Susan Sontag and Henry Fairlie live longer, and yet we can’t but flinch at his racism, his truculent Zionism and interventionism, his sabotage of the welfare state and efforts at healthcare reform, and of course his willingness to let The New Republic, under his watch, publish a lot of heinous and outright fraudulent articles. Life expectancy in many parts of the United States is lower now than it was when Jimmy Carter was president and Peretz was learning his ropes as publisher of TNR; and while no one can simply blame Peretz for this, or even lay the lion’s share of blame at his feet, he did arguably play his own part in making America a less healthy, less egalitarian, less free, and less enlightened place.

Under Peretz’s leadership, The New Republic was a lively magazine that invented a style of neoliberal snark and sometimes irreverence that, while not as hegemonic as it was in the 1990s, still has journalistic imitators. Echoes of this style continue to reverberate in many publications, from Slate to Tablet to The Atlantic to The New York Times’ op-ed page. Peretz’s TNR hired and nurtured scores of talented journalists, chief among them Hendrik Hertzberg, John Judis, Robert Wright, Margaret Talbot, Peter Beinart, and Michelle Cottle. True, the staff leaned heavily white and male and also toward Harvard alumni, highlighting privileged voices even more than the dismal standards of the rest of the media. Further, the magazine also published more than its share of unsavory characters and fabulists: Stephen Glass, Charles Murray, Steven Emerson, and Michael Ledeen, among others. Peretz says his publishing philosophy at The New Republic, when working with his editors, was: “My bullshit goes in, so does yours.” In aggregate, this meant Peretz’s New Republic published an enormous amount of bullshit—his, but that of many of his editors too. The magazine promoted many of the worst decisions in modern American history–the killing fields in 1980s Central America, the invasion of Iraq, the downgrading of diplomacy in preference to military solutions in foreign policy, the neoliberal economics that has fueled inequality and instability, the brutalization of the Palestinians, the revival of scientific racism, and the persistent whittling-down of the welfare state. And this is only a partial list.

Having said that, The Controversialist is an absolutely terrific book that I can’t recommend highly enough. Anyone who cares about American politics should read it. To be sure, Peretz is often in error: To pick just one example, he claims that “the first time that journalists were regularly on TV” was in the 1980s, on shows like The McLaughlin Group. Meet the Press, which first aired in 1947, would like a word. And many of his other claims or characterizations of people are demonstrably false or absurd. Yet, despite this, The Controversialist clarifies how a powerful segment of the ruling class thinks and operates. There’s no other book that so clearly illuminates the moral, intellectual, and political corruption of neoliberalism. Susan Sontag never gave him thanks, but I will. Thank you, Marty, thank you!

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks

The late actor and director leaves behind a roster of classic films—and a much safer and juster California.

Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments

Dev Hynes moves between grief and joy in Essex Honey, his most personal album yet.

Ars Poetica with Backup from The Clark Sisters Ars Poetica with Backup from The Clark Sisters

after “Is My Living in Vain?”, 1980

Helen DeWitt and Ilya Gridneff’s Sweeping Anti-War Novel Helen DeWitt and Ilya Gridneff’s Sweeping Anti-War Novel

Your Name Here dramatizes the tensions and possibilities of political art.