Is It Possible to Suspend Disbelief at Ayad Akhtar’s AI Play?

The Robert Downey Jr.–starring McNeal, which was possibly cowritten with the help of AI, is a showcase for the new technology’s mediocrity.

The cast of Lincoln Center Theater’s production of McNeal.

(Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmer)

Midway through Ayad Akhtar’s new play McNeal, a deepfake appears of Robert Downey Jr., who stars as the title character. The image is as unsettling as it is underwhelming—it fails to provoke a suspension of disbelief. Yet the animation (manufactured by the studio AGBO) is not entirely out of place in a work that often seems more like a simulacrum of a play than the red-blooded real thing.

On the day McNeal opened at Lincoln Center Theatre, Akhtar made a somewhat shocking admission in an interview with The Atlantic: He enlisted AI in writing part of the play. As he told The Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg, “I wanted some part of the play to actually be meaningfully generated by ChatGPT or some large language model—Gemini, Claude. I tried them all.” In the wake of the announcement, critics have discounted Akhtar’s use of AI—or were altogether ignorant of the fact that he had used LLMs.

One critic even made the misleading claim that “the script is 0 percent AI.” To be fair, McNeal doesn’t go out of its way to dodge these suspicions. Its set is as sleek as an iPhone and makes the audience feel as if they’re trapped in an infernal computer program. In a perhaps unwitting display of AI’s propensity to hallucinate, the 90-minute drama is a decoupage of sources as disparate as King Lear, Ibsen’s The Master Builder and Hedda Gabler, and Kafka’s “Letter to My Father.”

McNeal begins with an invocation to AI. On a live-feed projection that resembles the screen and blinking cursor of ChatGPT, the question appears: “Who will win the Nobel Prize in Literature this year?” When the software declines to make predictions about the likelihood of the play’s titular protagonist winning, we hear a voice denouncing it as a “soulless, silicon…suck-up.” That voice belongs to Jacob McNeal, an egomaniacal and alcoholic author whom we first see in a doctor’s office, where his physician (Ruthie Ann Miles) warns him he’ll face “Stage 4 liver failure within three months” if he keeps drinking. The warning, courtesy of an AI program called Suarez, is our first glimpse into how deeply artificial intelligence has permeated daily life in this vision of the near future. The checkup is interrupted when McNeal receives a call from an unfamiliar Swedish number.

In the next scene, McNeal delivers his Nobel speech, focusing less on his own oeuvre than on AI’s dominance in the literary world, where it is not “just remaking stories, they’re remaking us.” He tells the audience that he even ran his own speech “through the chatbot just to see” before reassuring us that “a few good cuts aside, I didn’t prefer its suggestions.” The line rhymes with something Akhtar recently disclosed to The New York Times: He told reporter Alexandra Alter that when he uploaded a draft of McNeal into ChatGPT and instructed the program to rewrite it in a Shakespearean style, he was gobsmacked with what it returned; still, he “used only two of the chatbot’s lines.” Generative AI, it seems, is a subpar understudy for writers.

While McNeal eschews the chatbot’s suggestions for his Nobel lecture, our prize-winning pasticheur does come to appreciate the “suck-up”’s proposals for dramatic scenes that borrow from “psychiatric papers on borderline disorder,” Oedipus Rex, the Bible’s parable of the prodigal son, the other aforementioned literary works, and even his dead wife’s diary entries. He commands ChatGPT to “rework these texts in the style of Jacob McNeal,” which sets off a chain reaction of career-imploding consequences. It spoils little to say that McNeal (and the fragments of a play-within-the-play) is not on par with any of the works from which it is self-consciously derived. The critic Jesse Green noted in his review for the Times that McNeal “rarely rises to drama”—a sentiment shared by several other reviewers, who have called the work a “bloodless and convoluted mess” that carries the “unreal tang of AI-generated content.” I have little to add to these impressions, with which I mostly agree. Even if it was Akhtar’s intention to make a somewhat clunky play—that is, to dramatize the limits of AI in generating riveting drama—the gambit fails to account for the lackluster central performance.

That its main character never comes across as a convincing novelist owes more to the half-hearted script than to Downey’s efforts. Without seeming to have realized it, Akhtar has given us not a drama about the labor of writing, but one on the labor of editing. The personage who wrote the novels Malice’s Marvel, Acts of Faith, Goldwater, and Falcon’s Flight is hardly in evidence in the play’s 90 minutes. Instead, we get a clichéd outline of a writer: someone who goes on and then off Lexapro, who feels obliged to attend book parties, who envied Saul Bellow early in his career, who considers woman “the great Other,” and who sticks in his oar in conversations with underlings. Above all, he is someone who converts his traumatic backstory into art. As he tells his literary agent Banic (Andrea Martin), “The job’s to give them pleasure, lift them to a place of beauty, order, truth. But you’re doing it because of the darkness. Pain is the motor.”

At best, one might say that McNeal’s central figure is someone for whom “writer” has fallen to the very bottom of his drop-down menu of identities. In one of the more realistic scenes, McNeal goes through his (assuming that’s the right possessive) new manuscript with Banic, asking to “stet” certain lines. Needless to explain, at some point all writers must become ruthless editors of their own work. Yet the two remain separate activities, and the distinction is not supererogatory: to edit something requires it to have been written first. It’s a truism that we live in an age when everyone can be a critic or writer, but McNeal inadvertently seeds a slightly different idea—that in an age of generative AI, more and more people will turn into unwitting editors. As a case in point, one review of McNeal was partly generated by AI: The writer, David Gordon, copied the text produced by AI as well as all of his strikethroughs and emendations. The result looks exactly like a track-changed document, a fitting response to a play that frequently resembles a Frankensteinian cut-and-paste job.

Problems further accrue when McNeal starts behaving in more overtly self-destructive ways. In a meeting with a fledgling reporter from The New York Times who is working on a profile of the new Nobel laureate, McNeal finds various ways to stuff his foot in his mouth. He asks the young Black journalist (Brittany Bellizeare) if she was “a diversity hire,” admits that he “envied Harvey Weinstein,” and blithely confesses to “reconstructing” the book his wife had been working on before she took her own life (a detail partly borrowed from Hedda Gabler, which Akhtar has called his favorite play). Despite being a prolific user of generative AI, McNeal acknowledges the limits of the technology: “It’s not a good writer. Not yet. Just makes everything fit better into the mediocre middle of things.” That “mediocre middle” is the zone where the play roots itself. In its failure to creatively synthesize and transcend its source materials, it demonstrates that large language models have not quite figured out how to artfully borrow from other sources.

In 2021, Akhtar delivered a Philip Roth Lecture in which he ruminated on the ways that “our affinities are no longer the result of our own interest or tendencies, but are increasingly selected for us for the purpose of automated economic gain.” In the wide-ranging talk, he canvassed several topics that have only taken on new urgency in the intervening years: the cascading logic of “attention traps”; the stickiness of emotions that traffic in the “new and alluring, the surpassingly cute”; the erosion of interiority by technology. While no explicit mention was made of generative AI, Akhtar ended by exalting the wisdom of the writer who relies on “her own sense of things” rather than the “singularity” or automating technologies that “masquerad[e] as a kind of knowing.” Which brings us to McNeal: The character would seem to be the very antithesis of the humanist that Akhtar extolled in his lecture. Yet it’s worth noting what Akhtar asserted at the start of his talk: “Saul Bellow once said of writing novels…the challenge was to put his best ideas to the test and hope that those ideas failed. The optimizing rhetoric of our digital utopist/billionaires has, alas, yet to be put to a litmus test as rigorous and resonant as the one Bellow lays out for literature.” McNeal has strong claims to being that litmus test. (And if there is a fatal irony present here, it’s that a number of Akhtar’s works, including several plays and his first novel, American Dervish, were among the books used to train generative-AI systems, according to a data set compiled by the Atlantic that was revealed last year.)

With its meta-theatrical tendencies and magpie energy, McNeal shares more in common with Akhtar’s semi-autobiographical novel Homeland Elegies (2020) than with any of his previous plays, which include the cacophonous finance drama Junk (2017) and the Pulitzer Prize–winning Disgraced (2012). In Homeland Elegies, one character gives this piece of advice to the narrator, an aspiring writer and an avatar for the author: “Everyone knows there’s not a new idea to be found anywhere under the sun…. The problem, beta, is that you have to do it well. You have to do it better than the ones you’re stealing from.” Homeland Elegies is more notable for its borrowings from life than from literature, though it’s possible to discern the influence of literary lunkers like Rushdie, Roth, and Bellow in its pages. The book’s smudging of fact and fiction is handled with a finesse conspicuously lacking in McNeal. The writing in Homeland Elegies never betrays the sense that someone was desperately feeding quarters into a chatbot, and the novel has two protagonists instead of one: Ayad, its narrator, who shares many biographical details with the author, and Ayad’s father. In exuberant prose, the book limns Ayad’s entanglements with various women, his financial setbacks, his lean years as a writer, his meetings with a Pakistani American investor, and his strained relationship with his father. Dr. Akhtar is revealed to have had an equally eventful life: A onetime cardiologist for Donald Trump with a debilitating gambling addiction, he endures, in the course of the novel, a bankruptcy, a lawsuit for alleged medical malpractice, and the death of his wife. Most poignantly, the book conveys how, after decades of living in America, Akhtar père continues to feel like an outsider.

If Homeland Elegies brokers a sense of narrative intrigue from its melding of disparate sources, the opposite is true of McNeal. The characters in the drama are publishing insiders, well-connected editors, and nominal writers who seem exclusively concerned with image management and whose inner lives remain inscrutable. We learn that McNeal was born to an Irish Yankee dad and a Jewish German-born mom and was raised in East Texas—all details that are dutifully trotted out for a post-Nobel puff piece but not enlarged upon. In a confrontational scene with his son, McNeal grouses that “I put you through private school and rehab” and paid for “your mother’s endless psychiatric bills”—and the son and the ghost of McNeal’s wife proceed to pantomime the worst platitudes of troubled teens and disturbed mothers. More troublesome, the scene is prefaced by an interlude in which McNeal explicitly prompts ChatGPT to “scan these journals and pull material for a scene in which a father and son confront a family secret.” Our mind leaps back to an earlier interlude in which the fêted author uploads Oedipus Rex and other works to the chatbot. These gimmicky AI transitions (the script unsubtly calls them “sources”) cast a pall upon all of the scenes that sprout off from them. The effect is not unlike scanning a book’s annotated bibliography before reading the text proper and is deflationary in the extreme.

The play ends anticlimactically with Downey reciting, in a voice as flat as a bedsheet, a monologue inspired by Prospero’s final speech in The Tempest. The self-consciously stylized language is a departure from the largely naturalistic dialogue that has come before: “What issue, were these forged of ones and ohs, / Or in a smithy warmed by human fire? / What consequence if Jake McNeal was as real / As I am now, or if no such fool e’er roamed / A Swiss clinic’s fated, paper halls.”

Dramatically, these are inert questions that raise the baleful suspicion that we’ve watched a play of no more consequence than a tensionless dream. At the same time, these are metaphysical quandaries that Akhtar the writer seems genuinely to be wrestling with. To the above questions, one can add more: Will an increasing number of playwrights and designers feel pressured, in the coming years, to use AI in their creative work? Will theaters have to roll out nutrition labels about the percentage of AI content in their plays? What will audiences look like then? To quote the Bard, the game’s afoot.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks

The late actor and director leaves behind a roster of classic films—and a much safer and juster California.

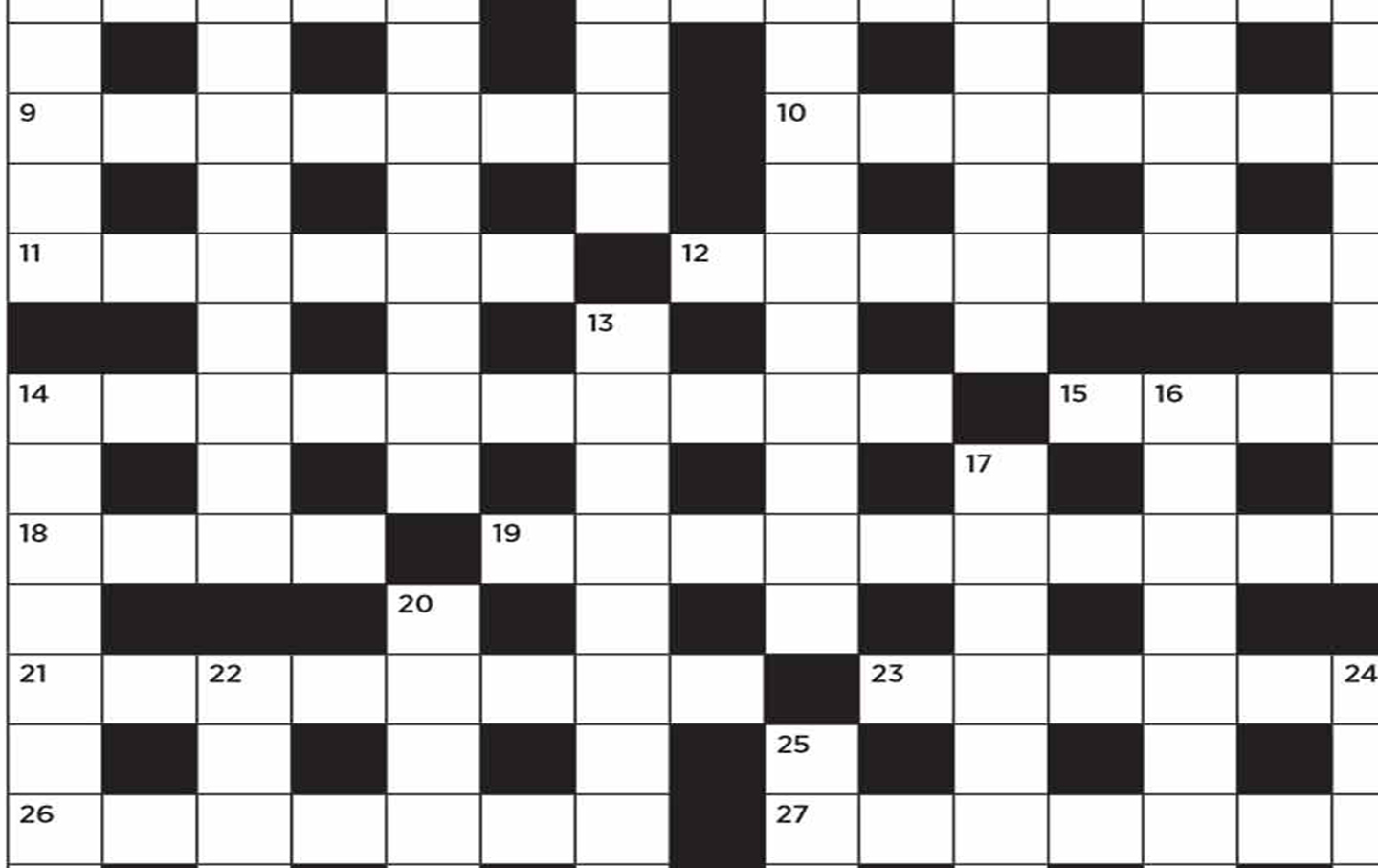

Solution to the “Big Event” Crossword Solution to the “Big Event” Crossword

If questions remain after reading this, please write to sandy @ thenation.com.

Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments

Dev Hynes moves between grief and joy in Essex Honey, his most personal album yet.