The Rise and Fall of the Marvel Cinematic Universe

How a movie studio and its head honcho redefined moviemaking for the worst.

President of Marvel Studios Kevin Feige, 2019.

(Photo by Jesse Grant / Getty Images for Disney)

Iron Man may have launched the most lucrative franchise in movie history, but when filming began in 2007, its script was half-finished. “We had to show up every day and we wouldn’t know what we were going to say,” Jeff Bridges recalled. “We would have to call up writers on the phone: ‘You got any ideas?’”

Books in review

MCU: The Reign of Marvel Studios

Buy this bookAs the journalists Joanna Robinson, Dave Gonzales, and Gavin Edwards detail in MCU: The Reign of Marvel Studios, the entire creative team on Iron Man was “working off plot points and concept art.” The hair and makeup department had roughly “five seconds” to change Leslie Bibb’s look for a party scene; one portion of the script was rewritten on the spot so Gwyneth Paltrow could showcase her knowledge of the paintings being used for set dressing. The “controlled chaos” of Jon Favreau’s improvisational directing even extended to one of the film’s most memorable sequences: Paltrow and Robert Downey Jr.’s impromptu escape from a gala at the Disney Concert Hall in Los Angeles. As one set decorator remembered: “All of a sudden, they’re going to the rooftop of Disney Hall and they’re kissing. And we’re like, what the hell?”

However frustrating for many members of the production team, Favreau’s approach worked wonders. Iron Man grossed a half-billion dollars globally, an unheard-of windfall for a studio’s debut feature, even one tagged with a brand name like Marvel. By 2008, superhero flicks had already been a dominant mode in Hollywood for the better part of a decade, thanks to the box office bonanza of 2000’s X-Men and 2002’s Spider-Man, which in turn inspired a legion of widely derided imitations (remember Halle Berry’s Catwoman?). Suddenly, the genre felt fresh again: The New York Times’ A.O. Scott wrote that Favreau wore the trappings of the superhero genre “as a light cloak rather than a suit of iron,” creating “a world that crackles with character and incident.”

This being Hollywood, it wasn’t Favreau who reaped the greatest rewards from Iron Man’s success, but the film’s producer, Kevin Feige, who was named president of the still-nascent Marvel Studios days after the film premiered. Now fully empowered to build an expansive cinematic universe, Feige began to drift away from hiring strong-willed directors whose vision for a particular film might conflict with his grand plan: a series of movies that together formed a single story arc called a “phase,” all meant to mirror the serialized format of a comic book.

Over the past 16 years, Feige’s tenure at Marvel Studios has generated $26 billion, making him the most revered Hollywood producer since Robert Evans presided over Paramount in the 1960s and ’70s. Yet while Evans successfully fostered a generation of directorial talent—the so-called New Hollywood of Francis Ford Coppola, Roman Polanski, and John Schlesinger—Feige’s innovation has been to wrest control of the creative process from the directors and writers, running movie production from the C-suite down.

Both Evans and Feige were known to exercise the power of final cut on their pictures, but while Coppola once reflected that Evans’s habit of deeply embedding himself within the quotidian churn of a film’s creation meant that, “ultimately, a mysterious kind of taste comes out; he backs away from bad ideas and accepts good ones,” there’s nothing mysterious about Feige’s taste. In an earlier interview with Joanna Robinson for Vanity Fair, Feige called himself “obsessed with deep mythologies.” Though he pays lip service to the idea that each individual film ought to stand on its own, Feige has always been most animated when talking in the lingua franca of the comic book nerd—continuity, or the ability to “bring that experience that hardcore comic readers have had for decades of Spider-Man swinging into the Fantastic Four headquarters, or for Hulk to suddenly come rampaging through the pages of an Iron Man comic…there is something just inherently great about that: seeing characters’ worlds collide with one another.”

In 2023, the novelty of the crossover began to wear off—and with it, the profitability of Marvel Studios. The past year’s slate of films demonstrated that the studio has run out of marquee heroes, with the likes of Ant-Man and Star Lord taking implausible turns as the headliner. The sagging box office culminated with The Marvels, which garnered $200 million this winter—$70 million short of what the film cost to produce. Making matters worse, Feige was forced to drop Jonathan Majors—whom he had planned “Phase Six” around—after the actor was convicted of domestic abuse. With the bloom fully off the Marvel rose, stars like Steven Yeun are now scrambling to escape from their commitments to the studio.

In their introduction to MCU, Robinson, Gonzales, and Edwards seem reluctant to believe that Marvel’s triumphant era might have indeed come to an end. “Although it may not have engineered show-business failure out of existence, it could easily survive a misstep or three,” they write. In treating Marvel’s dominance as “inevitable,” the authors ignore a truism of Hollywood: Genre films work until they don’t. The industry has been ruled by fads throughout its history, from the westerns of the 1950s to the sci-fi boom of the ’70s and the erotic thrillers of the ’90s. In each case, studio suits hammered away at a formula until they started losing money—a sure sign the audience was ready for something new. In their eagerness to canonize Kevin Feige, the authors of MCU unwittingly demonstrate the executive’s shortsightedness. Over the course of the past 15 years, Feige has drained every bit of fun from the MCU, obsessing over interconnections, continuity, and IP Easter eggs instead of allowing his filmmakers to embrace their idiosyncrasies. In the process, Marvel has taken what was once a collection of standout genre films and drowned them in a faddish flood that is only now beginning to recede.

“Other studios repeatedly tried, and failed, to find an IP steward who could replicate Kevin Feige’s accomplishments at Marvel Studios,” the MCU authors write just after recapping the glories of 2019 (namely, the studio making an astounding $3.9 billion off just two films, Captain Marvel and Avengers: Endgame). “The job appeared to be nearly impossible, requiring a precise balance between what was best for the brand and what was best for the characters”—with directors, writers, and visual effects artists not really figuring into the calculus. As the showrunner Dan Harmon joked to them, “Orson Welles is not going to work well at Marvel.”

Nevertheless, elsewhere in the book, the authors write that Feige “had an inarguable talent for getting creative people to do their very best work,” a risible assertion they support with the case of Joe and Anthony Russo, a pair of brothers who had mostly labored in TV before Feige hired them to direct Captain America: The Winter Soldier. By 2013, when The Winter Soldier entered production, “Marvel Studios trusted its [in-house special effects] artists so completely that it [had] started building movies around the splash-page images they created, an extraordinary inversion of the usual Hollywood approach where visual artists are hired to render images after a screenplay is written.” That meant two-thirds of The Winter Soldier “existed in pre-viz before it was shot, taking the guesswork—and the spontaneity—out of the production process.”

This was a distinct break from traditional moviemaking (including films like Iron Man), where art departments are limited to creating concepts before a script is ready. Instead, starting in 2010, the story structure for Marvel films was determined not through fostering a character’s development, or even creating a coherent plot, but by the need to reach a climactic sequence of visual effects: a big fight scene, followed by a picking-up-the-pieces denouement that served as scene-setting for the next feature.

When Feige approached Joss Whedon to work on The Avengers in 2010, Marvel had already “decided on some important moments in the movie—the studio knew, for example, that it would end with a huge battle against aliens in New York City, and had already started generating concept art for that sequence—[but] it was unsure how to unite its disparate heroes as one team.” Likewise, Whedon was instructed to include a “high-tech flying aircraft carrier” and that the film’s villain, Loki, should “wield the Cosmic Cube” (later renamed “the Tesseract”). By the end of 2010, Marvel had made its “extraordinary inversion” of filmmaking’s traditional creative workflow official by establishing an in-house visual effects department that would take a first pass at every idea Feige dreamed up.

The predominance of visual effects—particularly in Avengers: Endgame, which featured an astonishing 3,000 shots that included CGI—is one-half of the formula that the authors of MCU call the “Marvel method.” The other half is the control that Feige and his lieutenants have over storylines, ensuring that each film fits into the larger arc of a grand, universe-striding narrative meant to unspool over the course of a “phase” constituted by a half-dozen films. While Favreau chafed at the inclusion of an after-credit sequence in Iron Man that would hint at a future Avengers film, the Russo brothers were happy to incorporate a “mid-movie infodump” in The Winter Soldier whose only purpose was to foreshadow a sequel. “Kevin was in there to make great movies,” one of his top aides, producer Craig Kyle, insists. “That could never be a guarantee until we could actually control the process.”

That attitude created an inevitable conflict with Edgar Wright, whom Feige first approached about directing an Ant-Man film after Wright’s comedic take on a zombie apocalypse, Shaun of the Dead, became a surprise hit in 2006. At the time, Wright seemed like a budding Favreau: a young, imaginative filmmaker with a distinctive voice who could make a Marvel property his own. But once Wright finally got a script together in 2011, the Marvel method was in full effect. While “Wright had established himself as an ambitious young auteur who controlled every frame of his film…Marvel Studios had also established itself as a studio that demanded control.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Nevertheless, Wright remained excited about the project, telling the authors that the “crazy premise” of a man who could shrink or grow at will offered a similar level of creative potential as the original Iron Man. His enthusiasm waned once he started getting notes from not just Feige but also Joss Whedon (who was serving as czar for all Avengers-related IP) and a board of toy and comic book executives at Marvel’s main office in New York. While Wright’s vision was for a stand-alone movie, the Marvel brain trust demanded continuity. At one point, one of Marvel’s in-house writers did a pass on Wright’s script that left the director “horrified…. swaths of dialogue had been altered, and references to the wider MCU had been shoehorned in.” A week later, Wright was off the film, even as principal photography was set to begin within days. He was quickly replaced with Peyton Reed, best known for helming Bring It On, the first in a popular franchise of cheerleader movies.

From one angle, Ant-Man was still a huge success: It fulfilled its intended purpose as the coda of “Phase Two” while still making $519 million. But the film itself was just more fodder for the canon, artless and perfunctory. Critics yawned: The Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw called it “reasonably amusing”; at BuzzFeed, Alison Willmore wrote, “No other Marvel installment has felt as weighed down by its obligations to the franchise.”

Robinson, Gonzales, and Edwards are strikingly defensive of the Marvel method, writing that it “favored strong managers, not auteurs.” After quoting film journalist Eric Vespe’s acerbic charge—“Marvel was bringing in all these journeyman directors who would do what the studio wanted, or these people who they could, frankly, bully”—the authors seem briefly aghast. They quickly backtrack: “The truth was somewhat more nuanced,” they argue, noting the latitude afforded to the Russo brothers as long as they “were willing to cede a measure of control” over “narrative and visual continuity.” With narrative and visual continuity off the table, one wonders what a director has left.

Given the profound financial success of Marvel Studios, it’s natural that the rest of Hollywood has sought to replicate it. Disney’s other tentpole franchise, Star Wars, has been the purview of executive Kathleen Kennedy since the company acquired Lucasfilm in 2012, with uneven results. (It’s no coincidence that the best Star Wars offshoot from her tenure has been The Mandalorian—another Favreau project.) Now that Mattel is looking to transform its toy catalog into a full-fledged franchise after the triumph of Barbie, it won’t be Greta Gerwig who is calling the shots but producer Robbie Brenner. Like Feige, she was elevated to the presidency of her studio soon after Barbie’s box office success.

The only real aberration from the trend of micromanaging producers is DC Studios, which poached Guardians of the Galaxy director James Gunn from Marvel last year. Gunn became cochairman of the studio along with producer Peter Safran, taking on a charge to revive their Superman and Batman franchises. Whether or not that arrangement succeeds—giving a filmmaker the same share of control over the business side of a studio as a career executive—won’t be put to the test until 2025, when new movies from each franchise will square off against Marvel’s latest Captain America picture and its attempt to revive the Fantastic Four.

Meanwhile, Feige seems to have realized that the glut of films and tie-in series on Disney+ that characterized the MCU’s “Phase Five” was a mistake. That’s in no small part thanks to his boss, Disney CEO Bob Iger, who, in the midst of slashing costs for the entire entertainment conglomerate, said at a conference last year that he had grown disenchanted with sequels and had begun wondering: “Is it time to turn to other characters?”

For now, Feige’s release calendar for 2024 has been scrubbed of all titles—not that viewers will be spared the typical spate of superhero fare, since Disney is still involved in the release of three films that fall outside of Feige’s bailiwick on the conglomorate’s sprawling org chart: a pair of Sony’s Spider-Man spin-offs, plus this month’s Deadpool & Wolverine. The first of those films, Madame Web, netted a paltry $15 million over its opening weekend back in February. That makes it hard to imagine that simply slowing down the pace of mainline Marvel releases will solve what ails the studio—though not for Robinson, Gonzales, and Edwards, who argue that the failure of many of the TV shows based on Marvel IP that were produced for Disney+ in recent years is due to the elimination of “a key step in the Marvel method: close scrutiny by Feige.” The authors turn to Joe Russo—ever the loyal soldier—to explain why other studios can’t replicate Marvel’s track record: “Simple. They don’t have a Kevin.”

The closest that MCU comes to addressing the headwinds facing the studio is when the authors articulate the dilemma created by its dynasty: “how to extend a story with no obvious endpoints, to keep familiar characters relevant, to constantly reinvent the formula for success without rebooting the whole enterprise.” Over the course of the book, the only answer to the quandary that emerges is to trust Kevin. For now, the executive seems to be betting that a year off from any proper MCU releases will generate the necessary excitement for, well, a reboot: The Fantastic Four, which will kick off “Phase Six” in 2025. But if widespread interest in Marvel is indeed waning, it’s no sure bet that returning to a more recognizable set of heroes will save the day.

More from The Nation

“The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy “The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy

The new show from the creators of The Office reminds us that their comedic style does now work in every “workplace in the world.”

The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…” The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…”

In his celebrated mea culpa, the German pastor Martin Niemöller blamed his failure to speak out against the Nazis on indifference. Was that the whole reason?

The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme” The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme”

Josh Safdie’s first solo effort, an antic sports movie, revels in a darker side of the American dream.

John Updike, Letter Writer John Updike, Letter Writer

A brilliant prose stylist, confident, amiable, and wonderfully lucid when talking about other people’s problems, Updike rarely confessed or confronted his own.

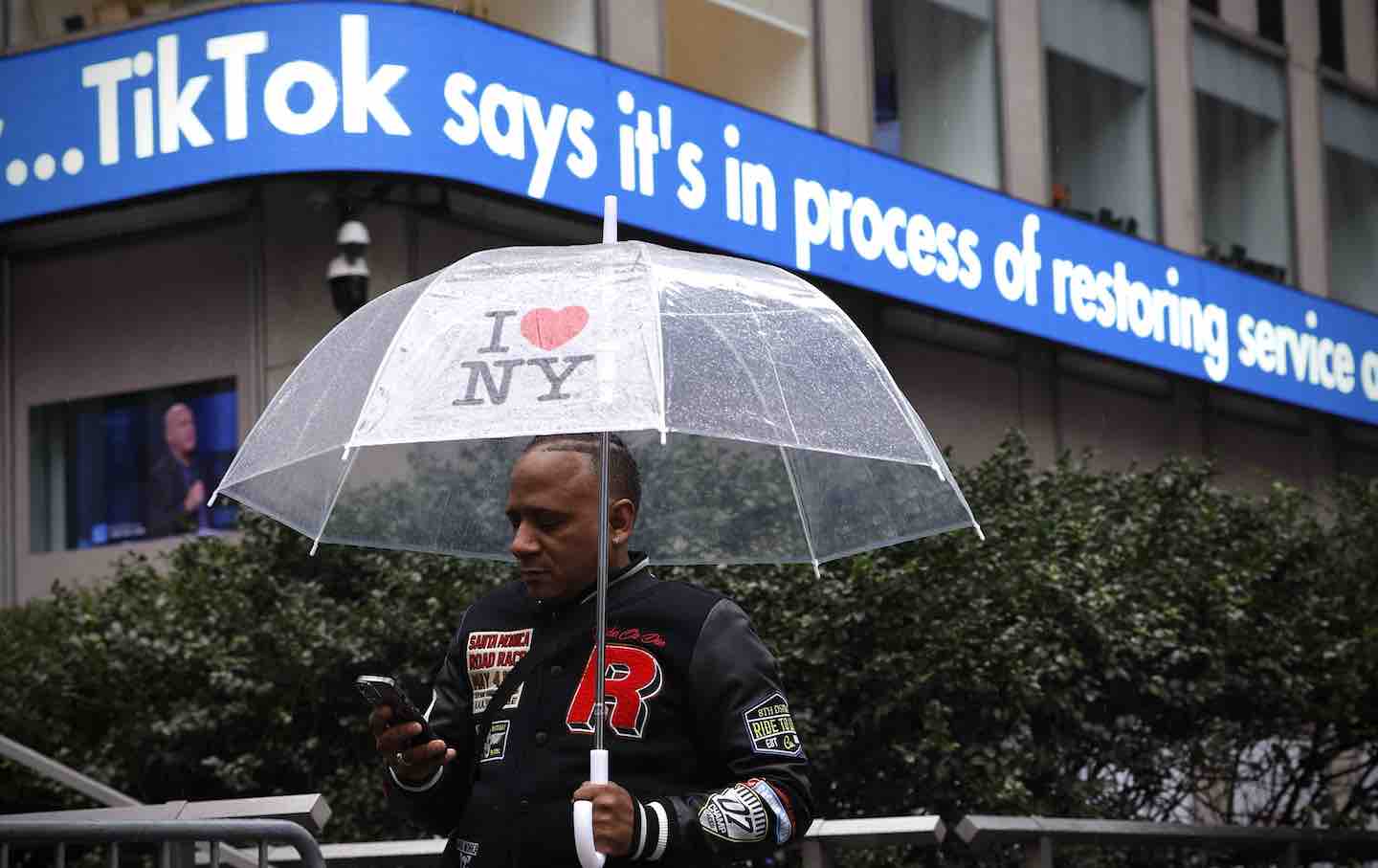

TikTok’s Incomplete Story TikTok’s Incomplete Story

The company has transformed the very nature of social media, and in the process it has mutated as well—from tech unicorn to geopolitical chesspiece.