The Trans Panic in Sports Is Nearly a Century Old

Michael Waters’s eye-opening history of gender and athletics in the lead-up to the 1936 Olympics reveals just how old this reactionary movement in athletics is.

Helen Stephens winning the Women’s 100m at the 1936 Berlin Olympics.

(Photo by ullstein bild / ullstein bild via Getty Images)

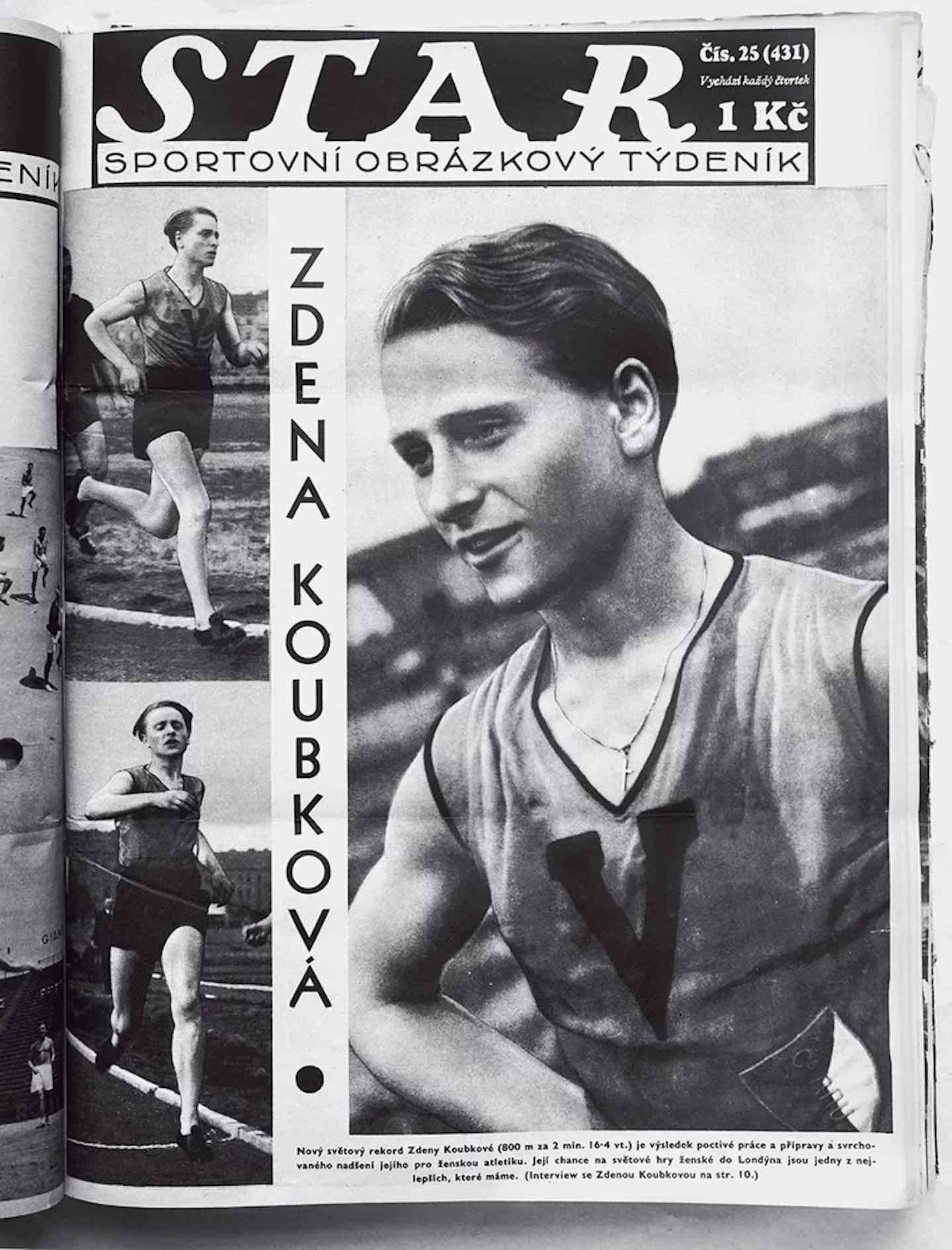

A conspiracy was brewing in the world of women’s track and field. Zdeněk Koubek had just set a new world record in the 800-meter run at a major track meet in London, but onlookers had their doubts. Didn’t Koubek seem a little masculine, some wondered? Was the Czech track star a man disguised as a woman, who was trying to cheat real women out of their deserved prize? A coach from South Africa, Bertie C. Sims, was so certain that Koubek had stolen the race that he threatened to pull his team from future competitions. It was sex fraud, he declared to the press. Canadian coach Alexandrine Gibb agreed, lamenting that her athletes had been forced to run against a man. “I had a dressing room full of Canadian girls weeping because they had to toe the mark against girls who shaved and spoke in mannish tones,” she wrote in an op-ed for the Toronto Daily Star. Gibb felt that many competitors—not just Koubek—were “extremely mannish” and had made the competition unfair. Her athletes were “real feminine Canadian girls.” Koubek, she implied, was not a real girl.

Books in review

The Other Olympians: Fascism, Queerness, and the Making of Modern Sports

Buy this bookIt turned out that Sims and Gibb were on to something, though not in the way they understood it. A year after Koubek won gold, he told the world that he intended to live as a man. He received surgery to affirm his gender, masculinized his name, and attempted to change the sex marker on his ID. Koubek introduced many around the world to the very idea of changing sexes. But when Koubek beat the field in the 800-meter, he was still living as a woman, competing as a woman, and was simply a stronger runner than the South African or Canadian athletes.

If you don’t remember Koubek’s story, that’s because it was largely lost to history. Koubek won the Women’s World Games, a now-defunct sports competition, in 1934, representing Czechoslovakia, a now-defunct country. Not long after he announced his transition in 1935, war broke out, and Nazi Germany invaded and occupied parts of Czechoslovakia in 1938. Following a brief period of fame, Koubek decided to blend in, marrying a woman and working for a car manufacturer, lest he draw the ire of Hitler’s regime, which began detaining queer and trans people.

But before the war, his transition was covered obsessively by journalists around the world, who portrayed him as a medical marvel and a peculiar human-interest story. Koubek was among a small wave of athletes, including Mark Weston, Willy de Bruyn, and Witold Smętek, who transitioned in the 1930s. The news of their transitions was met with praise, wonder, and, of course, fierce backlash. The ensuing backlash to these athletes and the effect it had on how gender is administered and policed in sports is deftly uncovered in Michael Waters’s The Other Olympians: Fascism, Queerness, and the Making of Modern Sports.

Waters’s book unearths the buried history of trans and intersex athletes in the 1930s, reintroducing Koubek and others whose public transitions brought surprising visibility to trans people in the early 20th century but were then forgotten. The Other Olympians focuses largely on the lead-up to the infamous 1936 Olympics Games in Berlin and shows how Hitler’s government initiated a regime of spurious sex testing to ensure “fairness” in athletics. Chiefly, Waters’s history dispels the myth that the current panic about trans athletes is a new one—it has haunted sports for generations, as fascism and nationalism helped birth the very idea of gender surveillance in athletic competition.

Much of how we understand sex today was unknown when Koubek was running at the Women’s World Games, and the language used to describe his transition reflected that. Some reports, as Waters recounts, referred to his transition as a “metamorphosis,” describing it in terms that seemed to insinuate it was something that had happened to him rather than a decision he made. A US newspaper explained to its readers that Koubek had been born “bi-sexual,” in a possible attempt to say he had parts of both sexes. Others implied he was intersex, framing his transition, inelegantly, as a “choice of either sex.”

No matter how Koubek was born, he decided to live as a man and wanted to compete as one after he transitioned. “How a government or regulatory body defines ‘sex’ is actually a subjective choice,” Waters writes. “One that, over the last century, governments and regulatory bodies have taken it upon themselves to make.” These arbitrary decisions, he continues, are “not reflecting some objective reality”: The traits that we are quick to assign men and women—such as XY and XX chromosomes—collapse as useful markers once we acknowledge genetic diversity, and hormone levels can’t determine gender either. The decisions made by states to police gender, then, have never been rooted in science.

As is often the case, these unscientific decisions were made by people who purported to be defenders of science. Wilhelm Knoll, the head of the International Federation of Sports Physicians, which advised the International Olympic Committee, was outraged that Koubek received positive press coverage. Knoll, who was an ardent member of the Nazi Party, set out on a mission to besmirch Koubek and other athletes like him. Knoll said that Koubek was “deliberately fooling” the public about his sex assigned at birth and “unfairly [made] use of superior physique, as a man, against frail women.” As a solution, Knoll demanded the implementation of sex testing before the 1936 Olympics, which he felt should include a physical examination of female athletes. The panic Knoll was trying to create was based on a fiction, one further muddled by his implication that Koubek was possibly assigned male at birth and competed as a woman to win races, only to then return to living as a man. Der Führer, a Nazi newspaper, circulated Knoll’s comments and thanked him for standing up against Koubek.

This unfolded in the months before the Berlin games and only intensified as they grew closer. Waters explains that “there was no coherent ideology or intellectual idea behind Knoll’s push for sex testing.” For Knoll, Waters surmises, “regulating women’s bodies was probably an extension of that fear of difference.” Indeed, the sex testing was of a piece with other Nazi policies ahead of the games that sought to block “unsuitable elements,” like one that all but banned Roma and Jewish Germans from participating in the Olympics.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Rushing to pass something before the games, the Olympic committee announced a rule allowing people to challenge the gender of a competitor, who would then have to undergo a sex test. This rule was “the birth of a regime of gender surveillance in sports,” Waters writes, and would become the basis for decades of unscientific, invasive, and humiliating sex testing that persisted into the 1990s.

Koubek didn’t compete in the 1936 Olympics, and neither did Mark Weston, another trans athlete at the center of Waters’s book. The policies that Knoll advocated for—with the support of Avery Brundage, the head of the American Olympic Committee—did, however, greatly affect Helen Stephens. Stephens was an American runner who fell victim to what Waters calls the “inevitable end point” of the backlash against Koubek and Weston. She was trouncing her competition—as a sprinter, but also as a shot-putter and discus thrower—and, at the height of her career, was accused of being a man. Stephens’s mother was forced to publicly confirm that her daughter was a woman. Stephens herself said she underwent a sex test that proved her womanhood, but the details of the exam remain unclear, and some at the time claimed no test happened. Still, Stephens was shaken up by the incident, Waters recounts, and mortified by the accusations that seemed to overshadow her crowning achievement: two gold medals (for the 100-meter and the 4×100-meter relay) at the 1936 Olympics.

While Waters spends little time commenting on the present, contemporary analogues to the subjects featured in The Other Olympians abound. Take, for example, Caster Semenya, who twice won Olympic gold medals for the 800-meter—the same race that Koubek mastered—but has been attacked for most of her career because her body naturally produces more testosterone than most women. But the symmetry I kept coming back to while reading the book is that both now and then, right-wingers and fascists used the cases of a few athletes to incite panic and implement regressive policies that hurt both trans and cis athletes. The backlash to Koubek hurt him and Helen Stephens in the same way that the backlash to the swimmer Lia Thomas is hurting plenty of cis and trans women and girls today.

Just look at recent examples of girls in sports who have had their gender questioned, such as the 9-year-old girl in British Columbia who sported a pixie cut in a track meet last year. A grandfather of one of her competitors allegedly interrupted the race to accuse her of being trans. “My daughter is cisgender, born female, uses she/her pronouns. She has a pixie haircut,” the girl’s mother, Heidi Starr, told the local news site Castanet. “He stopped the entire event. He also pointed at another girl who also had short hair. He then piped in and said, ‘Well, if she is not a boy, then she is obviously trans.’” Starr said the man went on to accuse her of being “a genital mutilator, a groomer, and a pedophile.” The incident, Starr said, “destroyed” her “daughter’s confidence.” And in Utah earlier this year, state school board member Natalie Cline posted a picture of a high school girl playing basketball on Facebook and implied she was transgender, leading to intense harassment of the athlete. In her subsequent, half-hearted apology, Cline said she posted the image because the girl “does have a larger build.” She went on to justify her actions, writing in the same post: “We live in strange times when it is normal to pause and wonder if people are what they say they are because of the push to normalize transgenderism in our society.”

Strange times indeed. Bleak ones too. This fomenting anti-trans backlash came to a head last week at the 2024 Paris Olympics, when Algerian boxer Imane Khelif beat her Italian counterpart Angela Carini, who quit after 46 seconds and said she had never been hit harder in her life. Citing vague claims from the International Boxing Association (one of the sport’s governing bodies which was recently banned from the Olympics) that Khelif failed a gender test last year, critics decided the competition was unfair because Khelif was not a woman. Author J.K. Rowling condemned the match, which she described as between a man and woman. the New York Post put Khelif on its cover with the caption “sting like a ‘he’” and called her a “male-testing boxer.” Former president Donald Trump lied about Khelif at a rally, saying she “is a person that transitioned.” Nobody criticizing Khelif seemed to care that she was born a woman, identifies as a woman, had been cleared by the International Olympic Committee to compete, and hails from a country where it’s illegal to transition genders. (Her critics also did not seem to stop and consider that Carini might just be a quitter.) Many of Khelif’s trolls said, without proof, she had XY chromosomes. And no evidence that Khelif has higher testosterone levels, like Semenya, has been published. What makes the fury particularly disingenuous is that it only came now that Khelif is winning. When she lost in the quarterfinals at the 2021 Tokyo Olympics, her current critics didn’t bat an eye.

The outrage about Khelif will feel startlingly familiar to readers of The Other Olympians, as nine decades later the invented and hateful debates about Koubek and Stephens repeat themselves. Waters’s book, then, has arrived at a timely moment, as the backlash against transgender rights is mounting, transgender people are being barred from sports, and female athletes are increasingly subject to unfair and invasive questions about their identity when they excel. The Other Olympians is a stirring excavation of important, forgotten trans history, and it’s also a warning about how easily the scales can tip against people who challenge outdated ideas about gender and sex.

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation