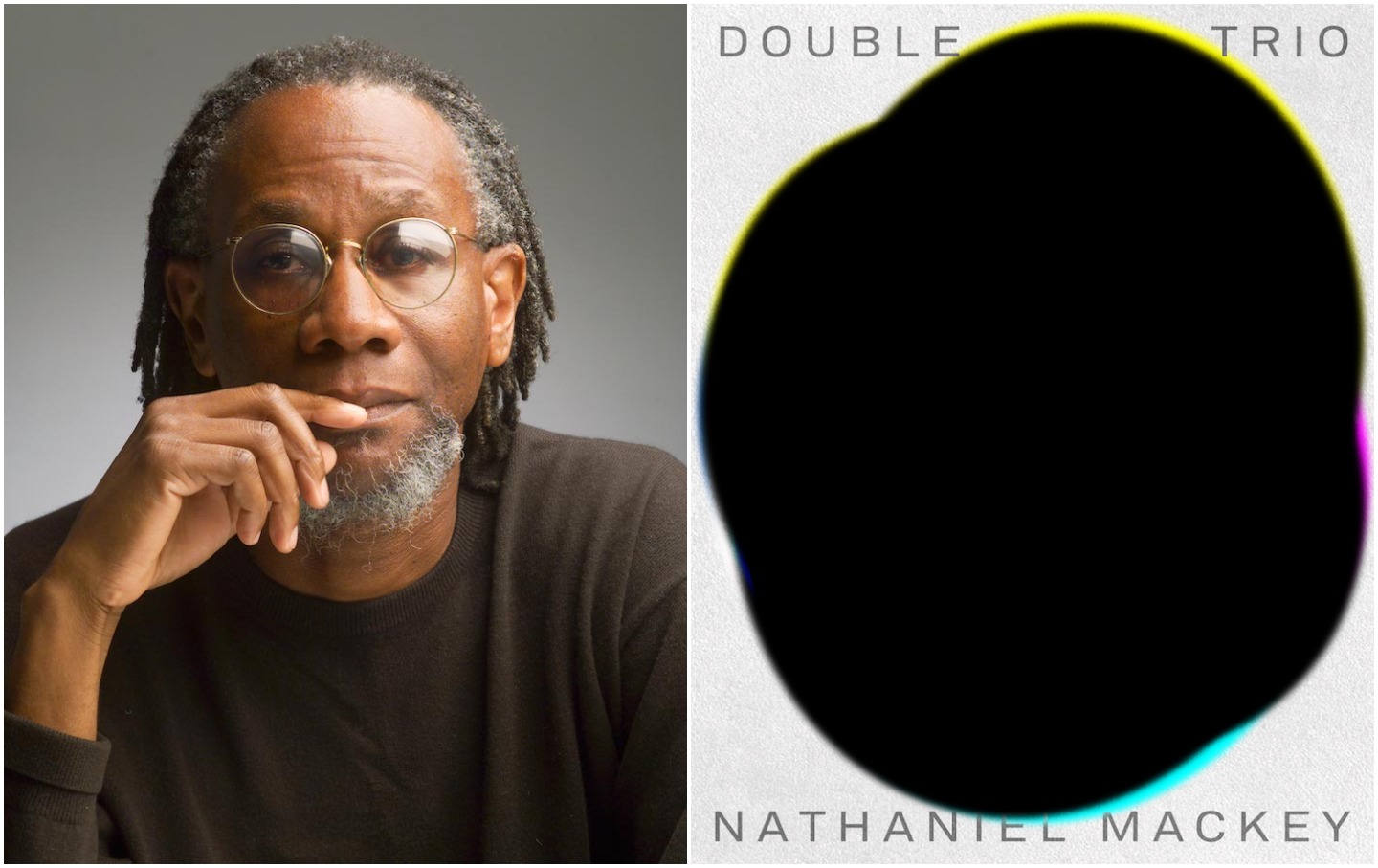

Nathaniel Mackey.(Courtesy of New Directions)

Toward the end of a conversation between Jacques Derrida and Ornette Coleman in 1997, the philosopher and the musician compare their experiences of estrangement from a “language of origin.” Coleman introduces the term to explain that, as a Black man from Fort Worth, Tex., whose first ancestors in America were slaves, he never knew the language his people originally spoke. Derrida offers in response that, as a son of French-speaking Algerian Jews, he maintains no connection to the language of his own ancestors. Both men now somewhat disarmed, Coleman pries, “Do you ever ask yourself if the language that you speak now interferes with your actual thoughts?”

Estrangement from one’s own origins and the struggle to think in a language under the control of an imperial power are two themes that pervade “Songs of the Andoumboulou” and “Mu,” the two long poems that Nathaniel Mackey has been writing in different installments for four decades. Double Trio, his new trilogy, is the largest collection of poetry Mackey has produced. As a whole work, it’s epic not only in size and reach but also in its synthesis of influences and themes into a compositional mode in which Mackey writes a history of alienation—of his own and of characters throughout history—from scratch.

“Songs of the Andoumboulou” is named after an album compiling field recordings of Dogon folk songs. The Dogon are a people native to West Africa whose mythology tells of an ancient race known as the Andoumboulou, a prototypical species prefiguring human beings. “Mu” is named after a pair of Don Cherry albums, released between 1969 and 1970. The two albums document some of Cherry’s early efforts to broaden the free improvisation he pioneered as a member of the Ornette Coleman Quartet, assimilating sounds and methods of different regional folk musics of Africa, the Middle East, and India. The two poems follow a cast of dozens—Netsanet the Beautiful One, Huff the true doctor, Anuncio the Elder and his lover, Anuncia, to name a few—writers, philosophers, and other rootless wanderers tripping across time and distance from India to London to outer space, from the cradles of civilization to the Middle Passage to the gyre of the present day, a series of love affairs, jam sessions, and spontaneous rituals bringing them together or pulling them apart.

Double Trio, named in homage to the records by Coleman and saxophonist Glenn Spearman on which two jazz ensembles improvise at once, continues this neverending dispersion outward. Although its movement is not exactly linear, allusions throughout its three books—Tej Bet, So’s Notice, and Nerve Church—refer to the major political events of the years Mackey spent writing it, which span most of Barack Obama’s second presidential term and Donald Trump’s first: the US presidential election of 2016 (“How could hair look so much like hay / we were asking, how could white be such a bright / or- / ange…”), the Boston and Paris bombings (“The news came in that / some- / where what could happen anywhere had hap- / pened, bombs gone off in Boston, bombs at a / kebab shop in Paris”), and the many police shootings and mass shootings of the last decade (“Twenty six dead, twen- / ty wounded”; “Nine people / had been shot in a church the radio said”; “a black man shot every- / where”). These references and Mackey’s citations of the many records that inspire him provide a body of dissonant motifs for this collection, forming what we might call a jazz fugue, written into the tension between the political atrocities of white supremacist America and the liberatory resonances of African American music.

In addition to being written under different titles, the poems in Double Trio can and must be read in multiple ways. Reading them for their personal, political, and philosophical significance almost runs parallel to reading them for the phrasing, articulation, and intonation that distinguishes them as exercises in improvisation. Many of Mackey’s lines, however knotted they are, make more musical sense when heard uninterrupted than when read repeatedly. This quality evokes Fred Moten writing on the jazz pianist Cecil Taylor, in whose spoken-word poetry Moten identifies “an anarchic and generative meditation on phrasing that occurs in what has become, for reading, the occluded of language: sound.” Mackey’s poetry, like Taylor’s, engages language musically in a way that reading for comprehension alone prohibits.

Among jazz musicians and listeners, “proper” melodic syntax is often considered uninspired. A bebop phrase that originates or resolves at the tonic, or the first scale degree, of the chord over which it is played is almost a faux pas. A phrase that begins at the third or the seventh scale degree, or jumps from the seventh to the second, skipping the first, is hipper. In Mackey’s poems, word order works in an analogous way, the arrangement of the parts of speech reversed so that style takes precedence over meaning in clauses like “opulent lip / one / got only abuse from we read about.” Likewise, to further embellish on a melody made up primarily of chord tones, a bebop player will often add an approach tone, or a note chromatically adjacent to a more consonant note. Mackey makes similar use of a robust vocabulary of near homophones. For any word he uses, he can always find a sonically adjacent word he can use to introduce another idea without disrupting the music of a line, as in a phrase like “abode / we / abided / by.”

These idiosyncrasies are not accidental but practiced—or they’re so practiced they occur even accidentally. So’s Notice, the second book of Double Trio, opens with three epigraphs. The second is a transcription of the opening bars of Miles Davis’s trumpet solo on “So What,” a solo that students of jazz often transcribe by ear to study the phrasing and articulation of modal jazz. The swing feel of most jazz improvisation alternates between longer and shorter notes of the same metric value, like metered poetry alternates between stressed and unstressed syllables. In “The Overghost Ourkestra’s Next—‘mu’ one hundred fortieth part,” the first poem of So’s Notice, Miles’s phrases echo in the scansion of Mackey’s lines: “War droned / on, money stayed on top”; “temporizing / remit, reminiscent romance”; “So it was or so we said or so we…” This is not just homage; it’s translation—how a poet trains as an instrumentalist.

Part of the project of Double Trio is for the musical qualities of Mackey’s poetry to engage the reader’s attention differently from its thematic content, and this troubled distinction between sound and meaning is also essential to Mackey’s political expressions regarding music and its role in Black American culture. In “Song of the Andoumboulou: 185,” a character named Sister C, an oracular presence who eventually composes a “new sensorium” called “The Sacred and the Senses,” is riffing on “the rigors of seeming defeat” when the “we” of the poem begins to speak along with her: “Babble be our boon we said without / words / or with words we made up or both ways, / choral insistence we cracked on Sister C with, / seconded her with, babble be our boon we / said / alongside everything she said. Such were / the dictates of seeming defeat, fugitivity’s / rigor.” The phrase “babble be our boon” recalls a comment by the author George Lamming on the community in his novel In the Castle of My Skin, a comment Mackey has quoted in multiple interviews: “The word is their only rescue.”

The rescue of the word, for Mackey, is the sense of play for which all languages allow, even a language a people must adopt once removed from their place of origin and robbed of their own language. Elaborating on Lamming’s quote at the University of Pennsylvania’s Kelly Writers House in 2017, Mackey told his audience:

So much slang in US verbal culture comes out of Black communities. That’s not an accident. It’s the treating of the given language as simply given. That has no claims to inevitable validity, truth, eternity, etc., etc. It’s just the beginning, just like a Tin Pan Alley tune for a bebopper is just the beginning. You don’t just play the melody, you look at the chord changes, and you do all these variations on it.

For Mackey, jazz and poetry are two different but cooperative practices by which Black people in America have defined and maintained a distinct culture, one with its own origins and languages. In a society in which white supremacy continually reasserts itself, with stubborn hostility, despite all movements for social progress, these practices are taken up out of necessity, but they can also be a source of solace that allows these movements to persist.

In a brief author’s note at the beginning of Double Trio, Mackey reveals that its three books correspond to the three tracks on the second side of John Coltrane’s 1966 album Meditations: “Love,” “Consequences,” and “Serenity.” Because the trilogy was written in a time of increasing social crisis, Mackey did not consider “Serenity” the most suitable note on which to end it. Therefore, he explains, “Nerve Church is ‘Serenity’ tweaked, modulated, or transposed to’ve become ‘Severity.’” For the touring band, the escaped and exiled tribe, the nomadic population of Double Trio, the challenge of living is to reconcile the utopian promise of music and language, the promise of an always distant but always accessible domain of sanctuary and freedom, amid the strangled, tone-deaf severity of a social order founded on intolerance. The latter is what Mackey calls “nonsonance,” the nonconsonance and nonsense of a life deserving and yet deprived of freedom. Nathaniel Mackey writes to keep the promise of art alive for those for whom nonsonance is nonstop. His word is their rescue. His babble is their boon.

Stephen Piccarellais a freelance writer whose work has appeared in n+1, The Believer, and The New Inquiry.