Norman Mailer was proud of his essay “The White Negro: Superficial Reflections on the Hipster.” Published in Dissent in 1957, it was reprinted in Advertisements for Myself (1959), Mailer’s anthology of selections from his fiction and nonfiction. It’s easy today to forget the immediate context: Mailer’s protest against the threat of mass destruction during the early part of the Cold War. It was absurd, the argument went, to behave as though life were normal or society rational when human beings faced daily the possibility of total extinction. Americans had to cultivate values that went beyond the concerns of middle-class comfort. “What the liberal cannot bear to admit is the hatred beneath the skin of a society so unjust that the amount of collective violence buried in the people cannot be contained.”

In “The White Negro,” Mailer argues that the postwar bleakness of the 1950s saw the appearance of “a phenomenon,” “the American existentialist,” the “hipster.” The hipster had the “life-giving answer” to the threats of both “instant death by atomic war” and “slow death by conformity.” By embracing death as an immediate danger, divorcing himself from society, the hipster—who was understood to be a white male—could exist without roots. This “uncharted journey” into the “rebellious imperatives of the self” meant encouraging the “psychopath in oneself” and the freedom to explore “the domain of experience.” Most Americans, Mailer held, were conventional, ordinary psychopaths, but a select few represented the development of the “antithetical psychopath,” who derived from his condition a radical vision of the universe.

Much of “The White Negro” is devoted to analysis of why the overcivilized man cannot be existentialist. The hip ethic is immoderation, adoration of the present. The image of the rebel without a cause, the embodiment of society’s contradictions, involved for Mailer the romanticization of the psychopath. “The drama of the psychopath is that he seeks love.” Hip is “the liberation of the self from the Super-Ego of society.” There are “the good orgasm[s]” of the sexual outlaw and “the bad orgasm[s]” of the cowardly square. The hipster belongs to an elite—rebels who have their own language that only insiders can convincingly speak, a language of found and lost energy: “man, go, put down, make, beat, cool, swing, with it, crazy, dig, flip, creep, hip, square.” As Mailer writes:

The organic growth of Hip depends on whether the Negro emerges as a dominating force in American life. Since the Negro knows more about the ugliness and danger of life than the White, it is probable that if the Negro can win his equality, he will possess a potential superiority, a superiority so feared that the fear itself has become the underground drama of domestic politics. Like all conservative political fear it is the fear of the unforeseeable consequences, for the Negro’s equality would tear a profound shift into the psychology, the sexuality, and the moral imagination of every White alive.

At the time, some white writers, Mailer among them, allied themselves with Black people who were urgently calling for American society to re-create itself. Like the juvenile delinquents, these white bohemians were drawn to the culture of the urban Black. “Any Negro who wishes to live must live with danger.” Unconventional action takes disproportionate courage, therefore “it is no accident that the source of Hip is the Negro for he has been living on the margin between totalitarianism and democracy for two centuries.” The Negro, in Mailer’s view, had been forced to find a morality of the bottom. “Hated from outside and therefore hating himself, the Negro was forced into the position of exploring all those moral wildernesses of civilized life which the Square automatically condemns.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

“The White Negro” had its specific origins in a quarrel with no less than William Faulkner. A mutual friend had sent Mailer’s sketch on school integration to Faulkner. In it, Mailer had said that white men in the South feared the sexual potency of the Negro and his hatred for having been cuckolded, historically, for two centuries: “The Negro had his sexual supremacy and the white had his white supremacy.” Faulkner replied that he had heard that idea expressed by ladies, but never by a man. Mailer observed that the sheltered Faulkner’s most intense conversations had no doubt been with sensitive ladies. Yet to be so dismissed by Faulkner annoyed him, and he decided to expand on his interpretation of a sexualized racial politics.

Whatever Mailer’s reasons, James Baldwin later said that he could not make any sense of “The White Negro”—that he could scarcely believe it had been written by the same man who recognized the complexity of human relationships in his novels The Naked and the Dead (1948), Barbary Shore (1951), and The Deer Park (1955). Mailer’s characters do not live on the road, Baldwin observed, yet he had fallen for the mystique of the Beats. Baldwin charged Mailer with maligning the sexuality of Negroes—and failing to see the limits in his point of view as a white man.

In his essay, Mailer reiterated the contention that offended Faulkner: that the white man feared the Black man’s sexual revenge. He himself was not opposed to miscegenation. Baldwin knew American masculinity because he’d been menaced by it enough, writing that the American Negro male was “a walking phallic symbol: which means that one pays, in one’s own personality, for the sexual insecurity of others.” He tried to convey in his work what life for the Negro was like, but he had become weary, he said, which was why he hadn’t anything to say about Mailer’s essay when it was first published.

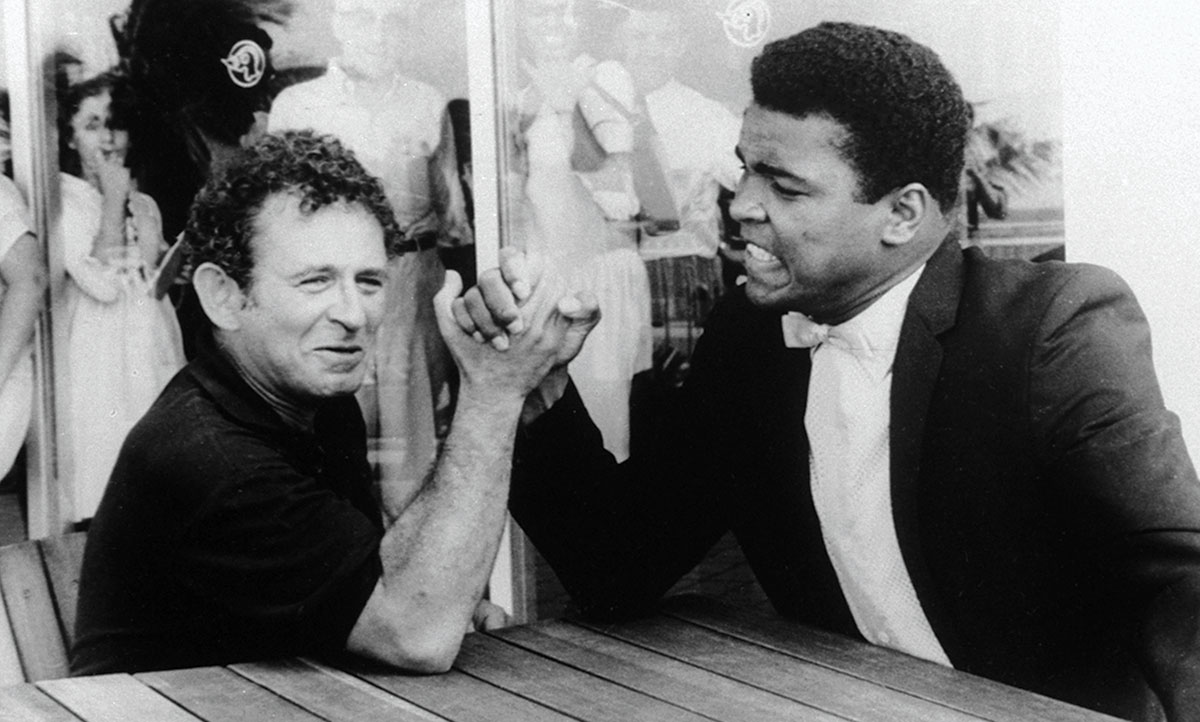

Yet two years later, Baldwin did respond. “The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy” was published in Esquire in May 1961 and reprinted in Nobody Knows My Name (1961), Baldwin’s second collection of essays. In Advertisements for Myself, Mailer had called Baldwin “too charming a writer to be major,” quipped that his prose was “sprayed with perfume,” and suggested that Baldwin lacked his—Mailer’s—street credibility. Baldwin admits in the essay that Mailer’s condescension hurt, but he doesn’t believe Mailer’s opinions will affect his reputation. Rather, he recalls with some eloquence the personal circumstances, differences, and similarities that prevented real friendship between the two writers. Then he takes aim: “The Negro jazz musicians, among whom we sometimes found ourselves, who really liked Norman, did not for an instant consider him as being even remotely ‘hip’ and Norman did not know this and I could not tell him…. They thought he was a real sweet ofay cat, but a little frantic.”

Mailer makes a distinction between hipster (of the proletariat) and beatnik (middle class). Baldwin didn’t—and he expressed contempt for the character in Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1952) who, when alone in Denver, seeks the Black part of town because that is where real life is. In The Subterraneans (1958), Kerouac’s white hoodlum succumbs to his paranoia that his soft brown bop-generation girlfriend will steal his white soul. Baldwin considered Kerouac and the Beats inferior to Mailer as writers, and he would be as impatient with the hippies in the ’60s as he had been with the Beats. He said his problem with white people was that he couldn’t take them seriously. They acted like crybabies—but their innocence was a danger to people like him.

Mailer’s argument that the Black man in America was born to be existentialist in outlook, because, unless he was an Uncle Tom, he had no other alternative philosophy that honestly addressed his circumstances, had antecedents. In his novel Native Son (1940), Richard Wright had anticipated the existential drama that follows when the feeling of what it is to be human has been lost through racial oppression. The urban loneliness Wright portrayed descended from Dostoyevsky, one of existentialism’s precursors. Partisan Review published parts of Jean Paul Sartre’s Anti-Semite and Jew in 1946, after which Wright read widely in existentialist literature. In The Outsider (1953), he attempted to formulate a more cogent philosophy about murder and irrational behavior. Wright eventually decided that his alienation was not due to his color but was man’s fate, and wrote another murder story, Savage Holiday (1954)—a so-called raceless novel, a psychoanalytical study about the singularity of existence. Some critics missed Wright’s insights into the racial context and were disappointed by the abstract application of existentialist ideas in his fiction, especially his notion of how the violent act defines human essence.

Baldwin didn’t see a quest for an authentic self in the sex and violence of Wright’s novels either. Bigger Thomas, the black murderer of both a white girl and a Black girl in Native Son, was based on a stereotype, Baldwin said. Wright himself was so sensitive to racial stereotypes he wouldn’t dance or play cards.

Michele Wallace agreed with Baldwin. In Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (1978), she said that the white man’s love affair with Black Macho began with Native Son. Wallace claimed that its message was that a Black man could come to life only as a white man’s nightmare. She credited Mailer with having been accurate in “The White Negro” about “the intersection of the black man’s and the white man’s fantasies.” But this was diagnosis, not praise. Though Eldridge Cleaver in Soul on Ice (1968) had been outraged by Baldwin’s criticisms of Mailer, in Wallace’s judgment Baldwin had suppressed his own ambiguities and ambivalences about gender and sexuality, because Black militancy, the political face of Black Macho in the ’60s, required it of him to do so.

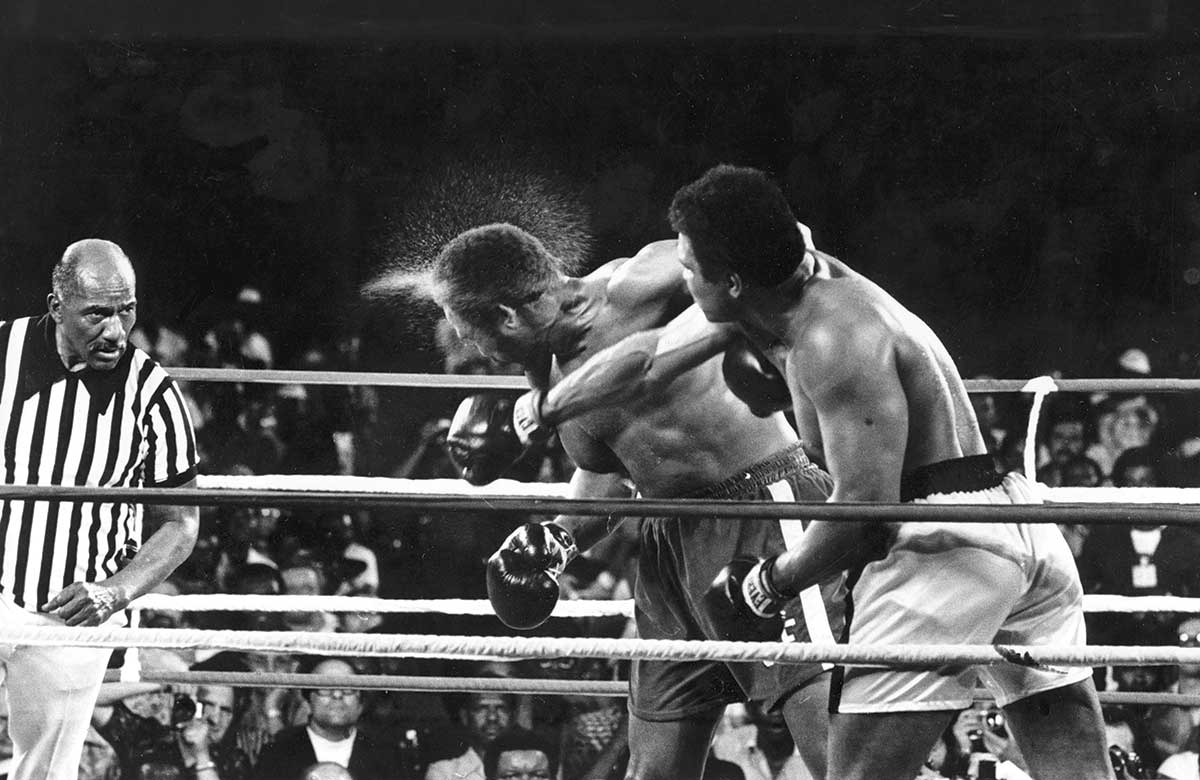

An obsession with the Black male also drove The Fight (1975), Mailer’s report on the heavyweight championship match between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman in Zaire in 1974. Mailer took the art of boxing seriously, and it was a subject he had some real knowledge of. However, reading him on the underworld of Black emotion, Black psychology, Black love—with Ali as exuberant as a white fraternity president and the darker Foreman the true African—we can’t help but recall Mailer saying of himself in “The White Negro,” “I am just one cat in a world of cool cats and everything interesting is crazy.”

Writing of himself in the third person—his signature move—in The Fight, Mailer admitted:

His love affair with the Black soul, a sentimental orgy at its worst, had been given a drubbing through the seasons of Black Power. He no longer knew whether he loved Blacks or secretly disliked them, which had to be the dirtiest secret in his American life.

In contrast to Mailer’s fame in New York, the indifference to his presence on the streets of Kinshasa had succeeded, Mailer wrote, in “niggering him; he knew what it was to be looked upon as invisible.” But the Zaïrois had “an incorruptible loneliness,” “some African dignity,” and when Mailer read Bantu Philosophy, by the Belgian missionary Placide Tempels, he was excited that the instinctive beliefs of “African tribesmen” were close to his own. People are forces, not beings. He rediscovered his “old love for Blacks—as if the deepest ideas that ever entered his mind were there because Black existed,” and he delighted in “the mysterious genius of these rude, disruptive, and—down to it!—altogether indigestible Blacks.” He also confessed once again to the old fear—the resentment of “black style, black rhetoric, black pimps, superfly, and all that virtuoso handling of the ho”—and envy that “they had the good fortune to be born Black.” He felt he understood what a loss the loss of Africa had been for Black people.

Anti-slavery literature was older than pro-slavery literature, but fear of interracial mixing was older than whatever the opposite of that was. Melanin infatuation doesn’t always imply wanting to interact with or to be intimate with Black people. It can mean a person wanting to be Black, to be like Black people, to import Black, have the Black style, or, especially for white men, to copy Black men. The Black hustlers Detroit Red learned from in The Autobiography of Malcolm X all came to a bad end. Yes to the glamour, no to the risk.

As the War on Drugs destroyed Black militant politics, hip-hop became the keeper of the real, the authentically Black. Hip-hop, an aggressive sound created by Black American youth on the East and West coasts of the United States, is “the dominant form of youth culture on earth,” Jelani Cobb proclaims in To the Break of Dawn (2007), his study of the hip-hop aesthetic. But the love of things Black, like existentialism, is a tradition, not a movement. That is why Baldwin kept saying, This is your problem, not mine.

After the slaughter of World War I, many white writers and artists lost faith in the supposed rationalism of Western society. This questioning marked a return yet again to the pastoral as an ideal—and Black people were thought to be close to the ways of the earth. Every negative in the depiction of Black people in American culture—shiftless, emotional, childlike, animal-like—became positive qualities. As the conventional paths to success that newly middle-class Americans chased in the 1920s were revealed to lead to the deformation of character, the exclusion of Black people turned into their supposed detachment from stress. Oppression gave Black people the freedom to want the right things from life.

The social Darwinism of the late 19th and early 20th centuries let white people put themselves at the top of the cultural pyramid, given the (to them) advanced development of their societies when compared with the decayed societies of Asia and South America and the barbaric ones of Africa. But then Picasso paid a visit to Matisse’s studio in 1905, and in 1907 he had his fateful encounter with African art in the Musee d’Ethnographie. After World War I—civilization’s catastrophe, as it was called—and after the 1919 exhibition of Paul Guilluame’s African art collection in Paris and the arrival of jazz there, the primitive, or primitivism, spread through the arts as a virtue, a reaction to the old social order. “Our age is the age of the Negro in art,” the Jamaican-born poet Claude McKay declared. “The slogan of the aesthetic art world is ‘Return to the Primitive.’”

McKay himself was more interested in primitivism in literature than he was in its expression in the visual arts. Batouala (1921), by the Martinican poet René Maran, made a considerable impression on McKay, as it did on Hemingway, as a novel that presents the consciousness of an African. Maran enjoys a sexual frankness in his tale of love and jealousy beyond anything D.H. Lawrence could have published about white people at that time in English. The anticolonialism of the novel is part of the natural life of the characters in their equatorial village. Batouala was one of the first literary works to present primitivism from a Black perspective as a positive political and social value.

In his study The Negroes in America (1923), McKay proposed that the root of the racial problem in the US was the old fear of social equality. To conceal the crimes of labor exploitation and lynch law, McKay said, the “American bourgeoisie” maintained a war between the races over sex. The sexual taboo that served the interests of the master class was a form of black magic. Sexual fear had acquired the force of instinct in the US, he contended.

The black writer Jean Toomer belongs more to the Imagists than he does to the Harlem Renaissance, but Cane, published in 1923—a collection of sketches, poems, and Expressionist-like drama that Toomer called a novel—was much emulated for its nostalgia for an instinctive way of life and its eroticized Southern landscape. Waldo Frank, a novelist born into an upper-class Jewish family who became known for his radical ideas, wrote the preface for Cane and published his own novel, Holiday (1923), on similar themes. However, in Frank’s romance of primitivism a white woman’s desire for the kinds of experience she imagines is available to Blacks delivers the Black man she attempts to seduce to a lynch mob.

Sherwood Anderson’s Dark Laughter (1925) shows Toomer’s influence in its telegraphic prose style, mixed with lyric poetry, and its determination to contrast the fecundity of the South with the sterility of the industrialized North. A Midwestern white man—everyone must be labeled these days—Anderson’s protagonist escapes the highly organized Chicago existence that has weakened his instinct for life, finding cures for the body and soul in the ease of New Orleans, among overly enthusiastic images of sexually anti-neurotic blacks. Anderson expresses much of what he has to say about the cultural and spiritual afflictions of white people in sexual terms.

Melanin infatuation circulated through American culture after the Jazz Age, mostly unexamined, unacknowledged. Mailer developed his hypothesis of hip during yet another postwar mood of repudiation. “For Hip is the sophistication of the wise primitive in a giant jungle, and so its appeal is still beyond the civilized man,” Mailer said in “The White Negro.” Mailer was 16 years old when he entered Harvard in 1939. Drafted upon graduation, he saw action in the Pacific in 1945. Veterans like Mailer had also seen something of the world, and the experience of meeting people unlike yourself is part of his ambitious, hugely successful first novel, The Naked and the Dead, published when he was only 25—a book Richard Wright read in Paris but doesn’t mention in his letters. Mailer’s was an American career, though he and Baldwin first met in Paris. If Henry James was Baldwin’s early model, then Hemingway was Mailer’s—especially when it came to projecting an image of masculine prowess.

The Brooklyn-raised Mailer was a New York City character, a founder of The Village Voice, a onetime mayoral candidate, his moods of dread or discontent always on public display. Making a spectacle of himself gave Mailer bragging rights, always bogarting onto center stage. Pugnacious in his intellectual style, he was not a good Jewish boy like Lionel Trilling, anglicized by the Ivy League.

In an essay published in Commentary in 1963, “My Negro Problem—and Ours,” Norman Podhoretz, another working-class Jew from Brooklyn, remembers as “bad boys” the sort of Black guys Mailer casts as natural dissenters. They persecuted Podhoretz when he was growing up in Brownsville in the 1930s. Italians and Jews feared the Negro youths who embodied “the values of the street—free, independent, reckless, brave, masculine, erotic.” The qualities he envied and feared in the Negro, Podhoretz said, made the Negro “faceless” to him, just as Baldwin claimed Blacks were to whites in general. And as a white boy, Podhoretz said, he in turn was faceless to them. Mailer wanted not to have this problem of intimidation, facelessness, shared or otherwise—not after the Holocaust. Summon instead the Maccabee who can hang tough with anyone, anywhere.

We all have changing relationships to writers, and how they seem to us down through the years is not fixed and can’t be when it comes to such complicated artists. I was not a reader of Mailer’s fiction. My college friends and I struggled throughThe Naked and the Dead and then read James Jones, a peer of Mailer’s as a novelist of their war, but because of the Vietnam War we preferred Joseph Heller’s blackly comic tone to their grit. I can recall the sensations that The Executioner’s Song (1979) and Ancient Evenings (1983) were as publishing events. I have a memory of Christopher Hitchens extolling the virtues of Harlot’s Ghost (1991) as a CIA novel. But my heart is with Miami and the Siege of Chicago (1968), Mailer’s reportage on the Republican and Democratic political conventions in 1968, and The Armies of the Night: History as a Novel, the Novel as History (1968), about the march on the Pentagon in 1967. The mere memory of those two titles makes me mourn again my older sister, an anti-war hippie who brought Mailer home in paperback. It took a while for serious citizens to like him as much as the young did, Baldwin said.

Many of Mailer’s readers grew up with him. Or not. Margo Jefferson remembers that she found The Prisoner of Sex (1971) “insufferable.” Oddly enough, it is this book, about his views on what he accepted as the natural inequality of men and women, that reminds us of the days when race relations were spoken of as a conflict between Black men and white men, for which white women were the prize and Black women were not in the frame. Town Bloody Hall (1979), the documentary about the panel discussion at Town Hall in 1971 between Norman Mailer and Jacqueline Ceballos, Germaine Greer, and Diana Trilling, captures the atmosphere of his public presence: combative, provocative, fired up. The women in the audience, plenty of whom knew Mailer, take his pronouncements on women as what they’d expect: condescending, out-of-date about equality and biology, and therefore irrelevant, just more of his shtick, which was to be outrageous. This, for the man notorious for having stabbed his second wife.

Mailer brought out nearly four dozen books in his lifetime, right up to his death in 2007. Do the biographies already out there have anything to say about Jason Epstein, Mailer’s longtime editor, who once said he really disliked “The White Negro”? Epstein, who has just died, remembered in his eulogy for Mailer in The New York Review of Books his “limitless ambition” and his sense of the writer’s “vocation” as being a commitment to explore “the deepest mysteries.” Baldwin said he wanted to die in the middle of writing a sentence. Time has obscured what he and Mailer once had in common, their love of purely literary qualities. Baldwin was certain that Mailer’s work would outlast the newspapers, the gossip columns, the cocktail parties. And Mailer’s own garrulity, he might have added.

Recently, news accounts have appeared claiming that a posthumous collection of Mailer’s political writings had been turned down by his publisher, Random House. The rejection was due, at least in part, according to the initial account, to the reaction of a member of the publisher’s junior staff to the word “Negro” in the title of the essay “The White Negro,” which was to be included in the volume. There were also rumors about declining sales, and speculation over how much Random House had paid Mailer over the years for his quest for the Great American Novel. Mailer’s family has stressed continued good relations between his literary estate and his backlist publisher. The estate’s literary agent also denies that any “cancellation” had occurred. In any case, the collection is to be brought out by Skyhorse Publishing, haven of the canceled.

What does this episode mean for Advertisements for Myself, which seems to be very much in print? Perhaps Mailer himself has become too controversial, given his misogyny, the violence in his personal history. But some people are asking, What is the difference between being canceled because you offend and your book getting turned down because your offensiveness represents a financial risk?

I don’t want to read Mailer again, but I don’t want to read any more Baldwin either, not until we get his letters. But while it may be too late for me to want to read Mailer’s books again—or even, most of them, for the first time—I wouldn’t want them not to be available in someone else’s future. As a historical document, “The White Negro” does not need to be defended, and as for Mailer’s ideas on Black primitivism, as an update on an American fetish they seem more in debt to Freud than to Sartre. Mailer said he was trying to kick benzedrine when he was writing “The White Negro,” which brings to mind Sartre going off speed in order to prove he didn’t need it. Sartre wrote his best book, The Words, without the aid of drugs.

Still, there is something cold turkey about “The White Negro” in its mania—but then Mailer was always on, out there. Sobriety was not one of his muses. In his time, critics talked a lot about Mailer’s saturation in the language, in the invention of his idiom, and how in his nonfiction each of his participant/observer narrators was a persona embarked on an adventure of mind and will. Writers must be free to take risks, to make their own mistakes. Mailer should be defended not for reasons of nostalgia but on principle.

There has always been a problem that what is being said about Black people and white people depends on who is saying it and where. There had always been the question of whether the superiority seen in Black vernacular culture was adequate compensation for political powerlessness and economic suppression. Intellectual heritage is now capital, and the belief that the fight for control of culture is political has become obsolete. Zora Neale Hurston resented white writers’ making money from Black material when she never got the chance to. Poachers. What separates the chaff from the wheat these days, and who decides and by what criteria? In print culture, the change in who gets to say what is grounds for expulsion from cultural memory signals a shift in power, a creation of new powers. The offended are not merely heard, they are enthroned.

I don’t believe in the non-AA use of the word “trigger.” You are not brought down by the encounter with a written work or an object of art to the extent that you would harm yourself or others unless you were already predisposed to do so and thrived on suppositions confirmed by your paranoia.

New powers need new standards: Is the aim the chastisement of the white gaze, control over sublimated and unsublimated aggression—or the placement of an additional apparatus of surveillance and accountability over culture? The market loves what are deemed icons, while the culture has come to suspect individualism. Even David Blight’s monumental Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom has moments when he regrets that Douglass thought of himself as exceptional. Never mind that Douglass could not have accomplished what he did had he not had this extraordinary sense of self. The age of auteurism is over. We all can be stakeholders in the fantasy that culture should be a safe place and that talent must be democratic, not a mystery.

I do not know how we got from wanting civilized workplace practices to imposing censorship—and doing so in the name of progressive intentions. John McWhorter was inspiring in his defense of the word “Negro” in a recent New York Times opinion piece. I was always told that my great-grandparents, listed either as “colored” or “Negro” in every official US Census, related to the word “Negro” in print as manifesting the respect they and W.E.B. Du Bois had won for themselves.

Writers’ works often disappear after their deaths—and then come back. Or not. Mailer has range in his subjects, but are his ideas just flawed, or are they so wrong they’re harmful? Eldridge Cleaver, rapist of Black women and white women, was excused back then because of white supremacy’s crimes. Did the murderer Gary Gilmore, the subject of Mailer’s Executioner’s Song, find dignity when he insisted on being executed for his crimes? Was the murderer Jack Abbott, whom Mailer helped get out of prison, worthy of what Mailer read into his miserable upbringing in the criminal justice system?

The history of ideas is unpredictable. Critic Sterling A. Brown was adamant that readers made the canon; academics seem to think they’re in charge these days. Perhaps time and other writers shape these matters, which are so fluid—what to call them? Along with the objections to what Mailer represents comes an exasperation with the ’60s, later generations fed up with hearing what to them sounds like the plea of impotence: that the wide cultural dimension is a crucial gauge to a free society. Artistic independence is fragile as social practice. What is being canceled is the status of art as sacrosanct, and that of the artist as belonging to an elect. Writing used to be considered a form of magic. Now it’s a profession. Behave.