Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s Voice From the Past

The Pakistani qawwali icon sang words written centuries ago and died decades ago. He’s got a new album out.

In June 2021, in a Nissen hut in the middle of Wiltshire, England, less than 30 miles from Stonehenge, Odhrán Mullan was looking through the archives of Real World Records. A project manager for the record label, which was created in 1989 by the musical polymath Peter Gabriel, Mullan spotted a tape that immediately sparked his interest. “Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan—Trad Album” was all it said on the cover. “I was always browsing, and I would spend a lot of afternoons after lunch there,” Mullan says. “I knew that would be the ultimate find—a Nusrat unreleased thing.”

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, the best-known qawwali singer of all time, died in 1997, two days after the 50th anniversary of Pakistan’s independence. After a career that spanned more than three decades, he had achieved immortality as the voice of a nation, often bearing the title Ustad, a word roughly equivalent to maestro or teacher. Khan’s stature was such that he was sometimes spoken about in the same terms as the saints he venerated through his music, the lyrics of which are drawn from Sufi poetry. His Pakistani biography, written by Ahmed Aqil Rubi, is punctuated with anecdotes of supernatural import, including miraculous escapes from deadly accidents and moments of spiritually exalted clairvoyance. (In one such tale, Khan dreams of a city in India that he has never visited but is able to describe in sufficient detail for his companions to identify as Ajmer Sharif; in another, a rural mystic makes him smoke four cigarettes before informing him that he has made Khan the king of East, West, North and South.)

Qawwali, which originated in the 13th century, is a style of music that’s unique to the Indian subcontinent. It is choral in nature, with a group leader joined by as many as a dozen supporting vocalists, known as the “party.” For centuries, those voices would have been heard unaccompanied, because of a prohibition against instrumentation in orthodox Islam. Today, most ensembles include a harmonium, a reed organ similar to an accordion that was introduced to India in the late 19th century, and tablas, a set of hand drums, while the rest of the party claps along in unison. Khan’s emergence in the 1960s brought the genre into modernity, not unlike the revival of medieval folk music that was happening in Great Britain at around the same time. He captured the imaginations not just of Pakistanis at home but of members of the South Asian diaspora abroad.

After the rest of the world discovered Khan in the 1990s, the acclaim was almost as breathlessly reverent as it was in his home country. The Village Voice rock critic Robert Christgau called him “the most awesome singer in the known universe,” and the singer Jeff Buckley compared him to God, Buddha, and Elvis. Khan is to qawwali what Paco de Lucía is to flamenco: at once its most famous export and a figure of gargantuan influence at home.

Conscious of Khan’s importance to the Real World brand, Mullan was eager to investigate the contents of the tape, which had been recorded in 1990, on the cusp of the artist’s global breakthrough. But before anyone could listen to it, the tape had to be baked, a process that involves sealing it in a controlled environment and heating it to between 130 and 140 degrees Fahrenheit. This treatment temporarily removes any moisture that has accumulated on the tape and allows it to be fed through the rollers of a tape machine. Once the music had been digitized, the staff at Real World Records sent the recording to Khan’s former manager, Rashid Din, who checked the four tracks against the rest of Khan’s repertoire. “He was able to say categorically that one track, ‘Ya Gaus Ya Meeran’—nobody had heard it before or since,” Mullan says. “And it just turns out that musically it’s quite a unique track, and the rhythms of the tabla and everything is just so unusual from the rest of his work.”

Last fall, Real World released the recording as Chain of Light, which becomes Khan’s final studio album, 34 years after it was recorded and 27 years after the singer’s death. Today, Khan’s legacy is undeniable, to the point that the pieces that form the bulk of the modern qawwali repertoire were almost all made famous by him. Though qawwali is a devotional music, Khan was responsible for taking it from the shrine to the record shop, turning it into a genre that could be enjoyed in a secular context. His use of sargam (a technique in which the voice is used like an instrument to improvise within the structure of the composition) to complement the music’s devotional aspects gave it an exploratory quality with immediate appeal to fans of modern jazz or psychedelic rock. To Khan’s hundreds of millions of fans in India and Pakistan and his admirers dotted across the West, the new material on Chain of Light amounts to a musical resurrection.

“Ya Gaus Ya Meeran,” meaning “O Helper, O Exalted One” in Urdu, is a composition in Raag Bhairav. In the music of the subcontinent, a raag is a melodic framework that’s comparable to a scale, but far more complex and prescriptive: It lays out the combinations in which the notes are to be arranged, lists the notes that must be given emphasis, and includes esoteric details like the time of day when a given raag is considered most effective. Bhairav is an ancient raag that includes the same notes as the double harmonic major, a scale that Western musicians tend to use when they want to evoke an Arabian or Moorish feel, as in Claude Debussy’s “La soirée dans Grenade” or, more recently, Dick Dale’s 1962 surf rock instrumental “Misirlou.” In “Ya Gaus Ya Meeran,” the music is the setting for a venerative poem about Abdul Qadir Jilani, a Sufi saint and scholar who preached in 12th-century Baghdad.

There is no universally agreed-upon definition of Sufism, but it typically refers to an Islamic devotional system that advocates the forging of a personal bond with Allah. Though it can be traced back to the years immediately after Muhammad’s death in 632 ce, Sufism truly flourished in the ninth and 10th centuries, part of the period sometimes referred to as the golden age of Islam. Sufis tend to emphasize God’s love rather than his justice and believe that the soul has the power to feel the divine presence in all things. The drinking of wine, for instance, is a recurring motif in Sufi poetry and literature; even though alcohol is prohibited in Islam, the intoxicating properties of wine are used as a metaphor to describe the ecstasy of spiritual enlightenment—one often invoked in the work of the best-known Sufi poet, Jalaluddin Rumi.

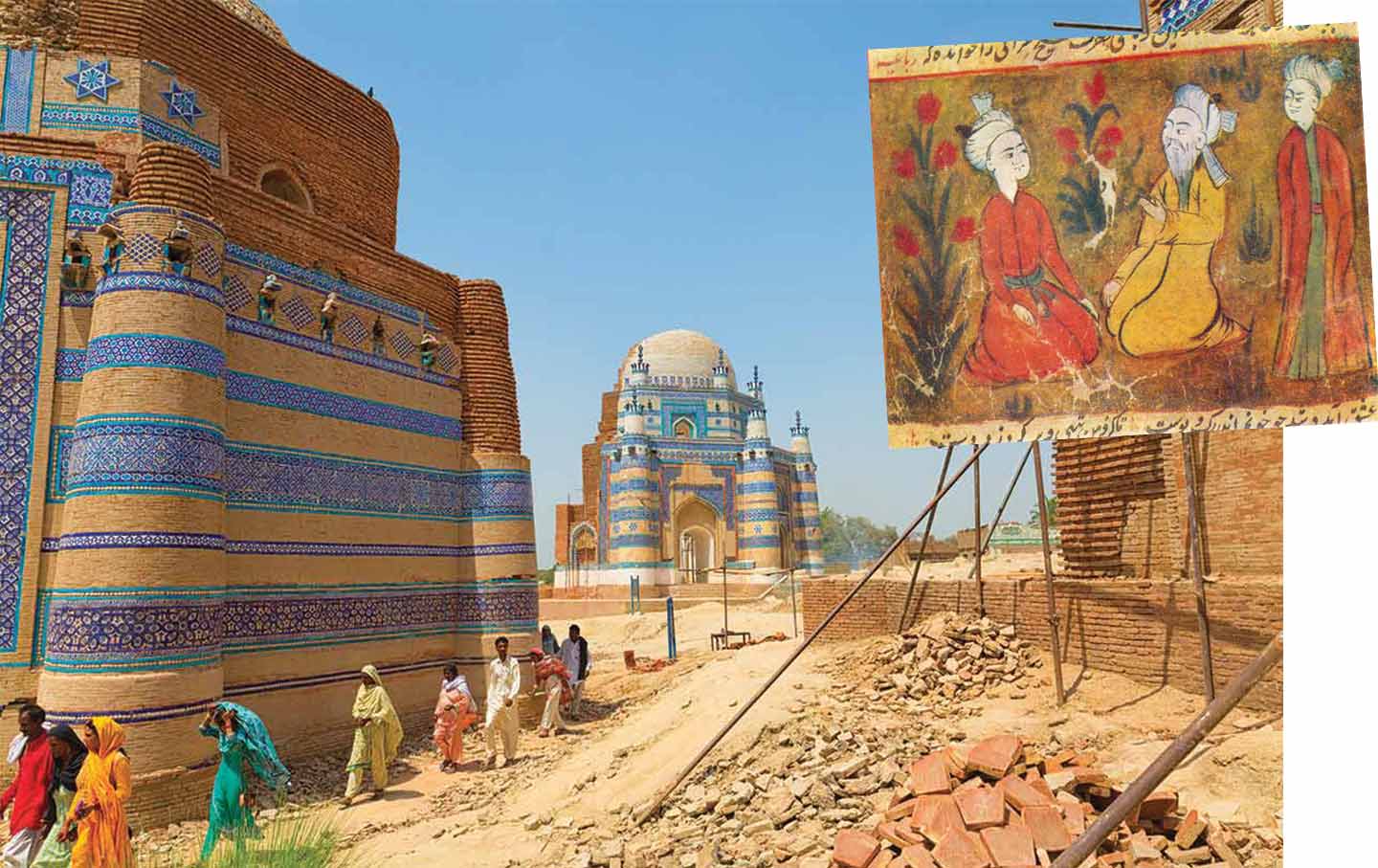

Sufism is transmitted from master to disciple in a silsilah, or chain, that is often traced all the way back to Muhammad, and this spiritual genealogy has made the veneration of preachers a cornerstone of Sufi art and music. In the subcontinent, qawwali developed over successive centuries of Muslim rule as the artistic arm of Sufism, which was patronized by the Muslim ruling elite because its similarities with Hindu mysticism made it an effective tool for nation-building. Since music has always played a significant role in Hindu worship, qawwali became the medium through which preachers were able to spread the message of Islam in medieval India—a practice carried out at Sufi centers, usually shrines built in veneration of particular saints or preachers.

These Sufi centers have become repositories of power in the modern era. According to a study by the economists Adeel Malik and Rinchan Ali Mirza, there are about 60 such shrines in Punjab, Pakistan’s most populous province, controlled by families who use their centuries-old religious authority to influence large voting blocs of disciples. Some “saintly descendants” run for office themselves, the most famous example being Shah Mahmood Qureshi, who served as foreign minister in Imran Khan’s government from 2018 to 2022. In order to maintain these Sufi shrines, the ethnomusicologist Regula Burckhardt Qureshi notes in her book Sufi Music of India and Pakistan, “saintly representatives rely on service professionals who are attached to their shrine by hereditary right.” Qawwals, who make up part of this indentured milieu, “stand in a servile or ‘client’ relationship of dependence to the shrine descendants.” To some extent, that dynamic persists today.

Before Khan rose to international fame, qawwals tended to earn the bulk of their living by performing in mehfils, or salons, for the rich and the powerful. Khan, along with stars like the Sabri Brothers and Aziz Mian, was one of very few exceptions. Even today, the weakness of copyright law in Pakistan and the attendant culture of piracy means that most musicians are unable to rely on royalties and remain dependent on patronage.

Since qawwali follows the Sufi model of hereditary training, there are entire households of musicians who have developed their own repertoire. The idiosyncrasies of each gharana—or specialist school of performance—have been honed over generations and sometimes centuries. But the intergenerational exposure of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, who remains the genre’s only global superstar, has led contemporary qawwals to neglect their own material in an attempt to sound more like him. “It is a huge mistake,” says Arif Ali Khan, a retired businessman who travels around Pakistan recording qawwals and classical musicians for an audiovisual project called The Dream Journey. “You can be a magician, but you will never be Nusrat. Nobody had a following like him in the past, and it’s unlikely anyone will have it in the future.”

Though his project has plucked a number of singers from relative obscurity, Arif Ali Khan paints a mixed picture of the health of qawwali. “There is a perception that artists are all struggling and hungry all the time, but at least in the groups that we’ve recorded, that’s far from the reality,” he says. “There are over a hundred qawwali groups in Pakistan who are making a living.” At the same time, the large size of these groups means that money is often stretched thin. “Qawwali involves eight or 10 artists at the same time, and very often you’ll find that some are family members but some are not, or some are family members who have their own family units that they need to support.” Indeed, Maulvi Haider Hassan, a qawwal from Faisalabad, Pakistan, who died in 2019, had four families—a total of 92 people—living with him.

It is to escape the degradation of this social status that Nusrat’s father, Fateh Ali Khan, is said to have wanted his son to eschew the family’s 600-year tradition of qawwali performance and instead train to become a medical doctor. The young Nusrat had other ideas. His insistence on continuing to practice alone eventually led his father to relent, and it was at his father’s funeral that Khan made his first public performance.

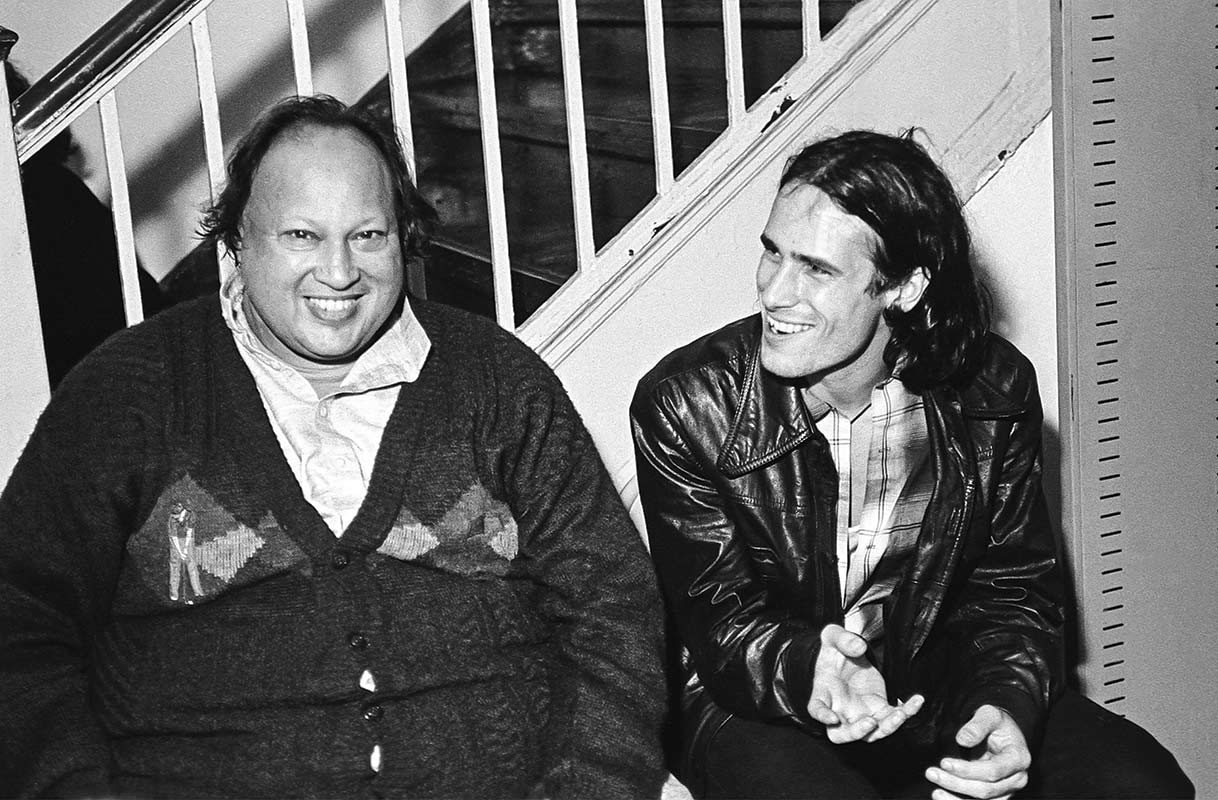

Peter Gabriel, who was instrumental in bringing Khan’s music to the West, was introduced to qawwali by Pete Townshend of the Who. (In the late 1960s, Townshend had become a disciple of the Indian mystic Meher Baba, whose complex religious philosophy incorporated aspects of Sufi teaching and had influenced the composition of the Who’s 1969 album Tommy.) Gabriel had helped found the World of Music, Arts and Dance Festival (WOMAD) in 1980, and Khan was booked for its 1985 event, which took place on Mersea Island on the eastern coast of England. By then, Khan was already famous in his native Pakistan and had been signed by the British record label Oriental Star Agencies. The label released more than 100 albums of Khan’s music and organized concerts for the South Asian diaspora community, at which the audience would shower him with cash during his marathon performances. But global recognition had remained elusive. Throughout the 1970s, the only qawwali group that had managed to break out internationally was the Sabri Brothers, who performed at Carnegie Hall in New York and the Royal Albert Hall in London. After Khan’s performance at the WOMAD festival, all of that changed.

“It was a cold night; the island was misty,” remembers Amanda Jones, the manager of Real World Records. “Nusrat had to be bundled up with blankets to keep going. But the audience were this completely new audience for him, and that was a kind of revelation for both sides, because the audience were so overwhelmed by the experience of seeing Nusrat. Very few of them had any cultural context for what they were seeing—certainly very few of them would have understood the lyrics. But it was such a great encounter. It was from then on that Nusrat decided that there was something exciting there for him to introduce his music to.”

When Gabriel was commissioned to write the music for Martin Scorsese’s 1988 movie The Last Temptation of Christ, he asked Khan to provide the vocals for the Passion sequence. The raag that Khan chose, Darbari Kanada, uses all the notes of the natural minor, a ubiquitous scale in Western music, but with a crucial difference: Two notes in the scale, the minor third and minor sixth, are brought up to pitch using a slow and stately vibrato. Legend has it that the Mughal emperor Akbar, having tired of listening to the natural minor, ordered his court musician, Miyan Tansen, to find a different way of treating the same notes. Tansen is said to have borrowed a similar-sounding raag from the Carnatic system of music, developed in South India, and adapted it to suit the emperor’s tastes. The name of the raag—Darbari means “of the court,” and Kanada refers to the raag’s origins in the music of the Indian state of Karnataka—recounts the history of its creation.

“This is a Hindu scale, sung by a Muslim musician in a movie about a Jewish rabbi, directed by a lapsed Catholic,” says the American film composer Richard Einhorn, whose own most famous work, Voices of Light, is inspired by Carl Theodor Dreyer’s 1928 film The Passion of Joan of Arc. The resulting music evokes a “not entirely rational experience,” he suggests, while remaining “anchored in some imagined origin for the Abrahamic tradition.”

Khan went on to release five albums of traditional qawwali music on Real World Records, beginning with 1989’s Shahen-Shah (“King of Kings”). By the end of the 1980s, the American “world music” phenomenon had created a market—and a record-shop section—for music from outside the English-speaking world. In Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, the genre had found another Ravi Shankar: an Eastern musician able to inspire awe and enchantment in Western listeners. A whirlwind of international tours and media appearances took him from London to Tokyo and beyond.

In 1994, Khan and Gabriel joined forces again to contribute a song to the soundtrack of Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers. While that burnished Khan’s credentials as one of the foremost vocalists of the ’90s, he was upset that his devotional music had been used in the background of a prison riot scene. “When someone uses something religious in that way,” he said, “it reflects badly on my reputation.” Regardless, he contributed two duets with Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder to the soundtrack of the prison drama Dead Man Walking the following year. With that, The New York Times noted, Khan had “finally entered the mainstream.”

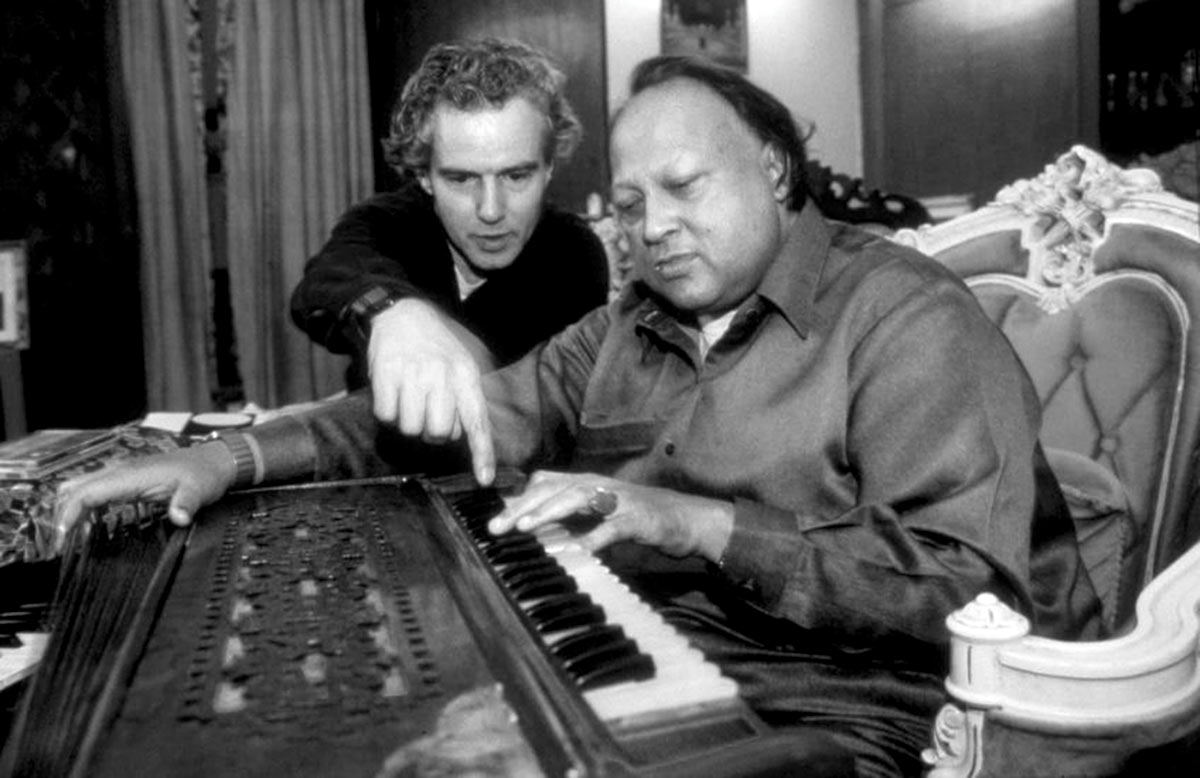

Perhaps the most interesting work Khan released in this period consists of the two experimental albums he recorded with the Canadian guitarist and producer Michael Brook, Mustt Mustt and Night Song. “Nusrat just found a way to do something that he was comfortable doing…on top of what I had done,” Brook says of their collaboration. “It sounds kind of fishy to say that we just went for it, but he was a master at what he did, so he was very good at adapting.”

Brook was also in the producer’s chair when Khan recorded the four tracks of the lost record—something he had forgotten until the tape was rediscovered three decades later. “I listened to it and thought, ‘Well, it’s amazingly good, maybe better than what we put out at the time,’” he says. “I think it’s his best qawwali that I’ve heard. He was at his peak, and everything was just working fantastic.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The title Chain of Light is taken from a line in “Ya Gaus Ya Meeran,” the otherwise unrecorded composition that stood out to Khan’s former manager Rashid Din: “Ek silsila-e-noor hai har sans ka rishta,” meaning “Every breath is related like a chain of light.” The other pieces on the record include material that Khan had previously recorded, but never with the production values of Chain of Light.

“Aaj Sik Mitran Di” (“Today the longing for my beloved”) is an illustration of the Sufi idea of finding the divine in earthly experience. It begins as a down-tempo exploration of what initially seems like secular love; as the tempo increases, and as the vocals gather intensity, the romantic idiom gives way to a celebration of the Prophet Muhammad, revealing him as the “beloved” of the poem’s early verses. “Khabrum Raseed Imshaab” (“Tonight there came news”) is a setting of the Persian poetry of the 13th-century mystic Amir Khusrau, who is sometimes credited with helping to create the qawwaliart form.

These subjects may not have come across to Khan’s growing audience when the album was recorded, but something did. “Look, our people understand the words and the poetry,” Din says. “But when he used to perform in front of white people, I used to sometimes ask them what they had understood. They would often identify certain pieces of spiritual music and say that their hearts had been affected, even without understanding the words.”

As Khan’s celebrity grew, his health began to deteriorate at an alarming rate. Weighing as much as 300 pounds and suffering from diabetes, he became reliant on twice-weekly dialysis to keep his kidneys functioning. During a trip to California in 1995, he was advised to have a kidney transplant, though it would take another two years before a donor was found. On August 11, 1997, Khan boarded a flight to Los Angeles to have the procedure. His nephew, Rahat Fateh Ali Khan, remembers that a great sadness had consumed his uncle on the car journey to the airport. “He was looking so downcast and worried,” Rahat says. “But he had a new album coming out, and he put on the tape in the car. Right until the end, he was still thinking about his work.”

Khan never made it to Los Angeles. Having fallen ill on the plane, he was dropped off in London and rushed to the Cromwell Hospital, where he died a week later after suffering a heart attack. The doctors at the hospital blamed his death on the use of infected dialysis equipment during his treatment in Pakistan.

In an echo of the ancient patronage system, Khan was still being booked for concerts even after his kidneys had failed. “The people around him did not care about his health or whether he was going to live or die,” says the Pakistani photojournalist Saiyna Bashir, who has spent the past two years researching Khan’s life for a forthcoming documentary. “Every minute counted; every buck that they could make before he died, they did.”

During his short life—he was only 48 when he died—Khan was responsible for turning qawwali into a global phenomenon. A live album of traditional qawwali released in his final year—Intoxicated Spirit, on the world music label Shanachie—was nominated for a Grammy Award, and archival live recordings, outtakes, and remixes have followed ever since. In his native Pakistan, meanwhile, there is a sense that the magnitude of Khan’s career has dwarfed everything that followed it. Rahat Fateh Ali Khan describes his uncle’s influence as a kind of prison. “It has been 27 years since he passed,” he says. “But the circle that he was able to draw around qawwali—the Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan style of performance—is one that nobody has been able to escape.” In Pakistan, this means that most qawwali groups perform the role of cover bands, appearing at weddings and parties where they faithfully reproduce the mainstays of Nusrat’s decades-old repertoire. There has also been a trend toward repackaging qawwali in the form of Western-style ballads, with synthesizers and drum kits replacing traditional instruments. In this context, the release of Chain of Light is raising hopes of a revival.

In the course of writing this article, I asked all of my sources what Khan was like in person, and the answers were almost invariably the same. He was described as a quiet and unassuming man whose fire burned only for the duration of a performance. When asked to speculate on the source of his ability to transcend language and geography, most invoked a quality of otherworldliness.

“He somehow touched some kind of common emotional resonance in people, and I don’t think anybody knows what it is,” says Michael Brook. “Someday, maybe someone will figure that out.”

More from The Nation

“The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy “The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy

The new show from the creators of The Office reminds us that their comedic style does now work in every “workplace in the world.”

The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…” The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…”

In his celebrated mea culpa, the German pastor Martin Niemöller blamed his failure to speak out against the Nazis on indifference. Was that the whole reason?

John Updike, Letter Writer John Updike, Letter Writer

A brilliant prose stylist, confident, amiable, and wonderfully lucid when talking about other people’s problems, Updike rarely confessed or confronted his own.

The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme” The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme”

Josh Safdie’s first solo effort, an antic sports movie, revels in a darker side of the American dream.

TikTok’s Incomplete Story TikTok’s Incomplete Story

The company has transformed the very nature of social media, and in the process it has mutated as well—from tech unicorn to geopolitical chesspiece.