Peter Handke’s latest novel, The Fruit Thief, translated by Krishna Winston, begins with a man going out for a walk. He is waylaid from the first step: Walking barefoot on the grass, he gets stung by a bee. The sting opens up a flood of thoughts—about the weather, a broken shoelace, the anatomy of bees, and whether bee stings are a cosmic sign. He declares, “Suddenly I felt fine about setting out without any map at all.” From there, the narrator begins a strange, sometimes inscrutable journey through provincial towns and fields, across rivers and into darkened woods. He is ostensibly in pursuit of a mysterious woman (the fruit thief), yet all the while our narrator keeps cogitating, describing, elaborating—even though it is unclear whether he wishes (or cares) if his purpose is understood.

Many of the Austrian writer’s protagonists are wanderers, and for the author, the work of noticing is a lonely struggle between the isolated self and the murky outside world. Language is the bridge: necessary for articulating what we observe and feel, but also fundamentally vulnerable to collapse. Handke subjects the words he uses to a microscopic examination: There is often a stunning ability to shift between abstractions (say, what it feels like to have a “successful day”) and the precisely sensory (say, a meditation on the sound of stepping on a manhole cover). Although they’re often detached in tone, this steady accumulation of impressions asks readers to question how attuned to their surroundings, and their sentences, they really are. The level of detail that The Fruit Thief’s narrator musters in his attempt to put the world around him into words creates a contradiction: Individual moments are exacting in their detail, but the world itself is vague, as if struggling under the weight of its elaboration. It can lead a skeptical reader to wonder whether the narrator—and, by extension, Handke too—is sometimes missing the forest for all the carefully described trees.

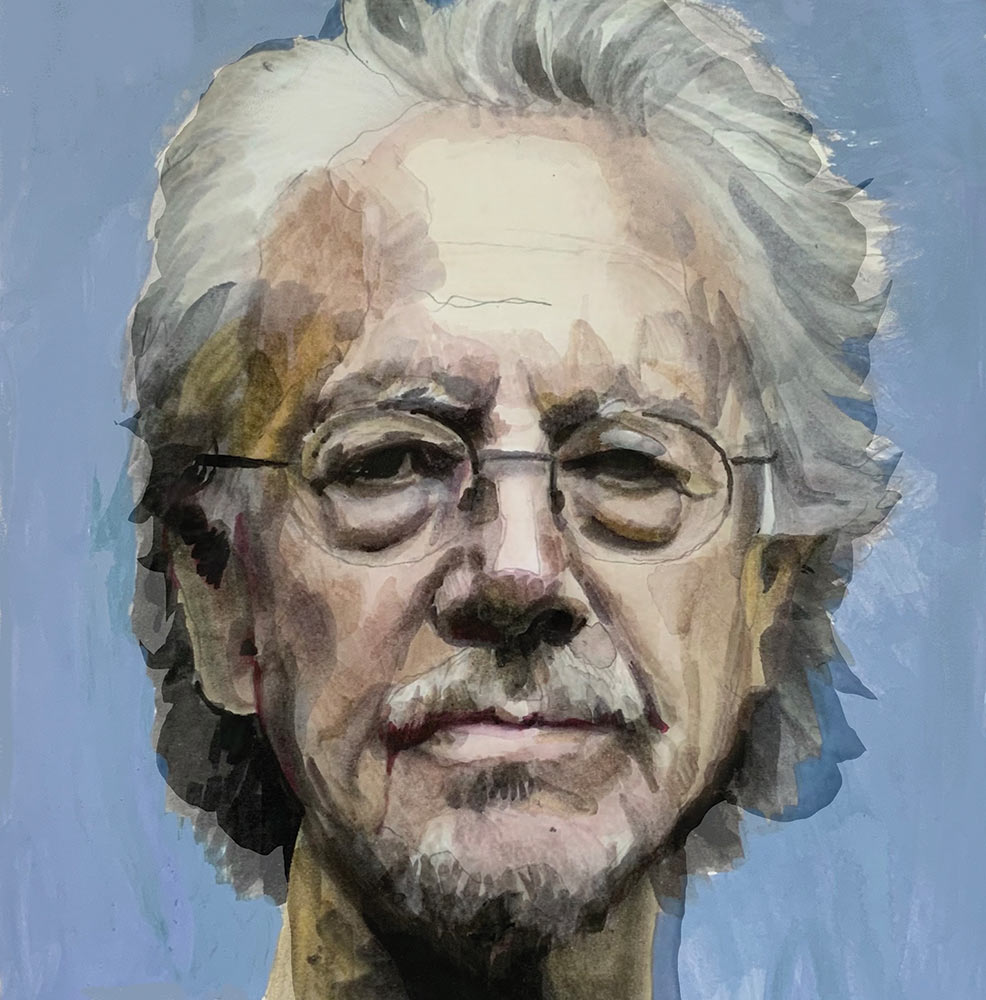

Although Handke first came to prominence as a playwright and novelist of prolific output (he’s the author of dozens of works), he has become much better known for his politics. His support for Serbia in the Balkan Wars of the 1990s, particularly his statements about the genocidal violence committed against Bosnian Muslims, has made him a pariah. A habitual contrarian, Handke embraced his outcast status and offered a bizarre disputation of the facts of the war that struck many as delusional, especially considering that he had only a glancing personal interest in Balkan politics—his mother was Slovenian, a fact he clung to with increasing intensity. In the years that followed, Handke has dug in even deeper. When Slobodan Milošević died in 2006 during his trial for war crimes, Handke spoke at his funeral. Years later, he was feted and decorated by the Serbian government. Despite the support of high-profile writers like Elfriede Jelinek and Karl Ove Knausgaard, his reputation has suffered. When he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2019, protest was widespread and one member of the Nobel committee promptly resigned, in part because of his politics.

Encountering Handke’s new book, prospective readers are left with a set of uneasy questions: Can the novelist’s gift for transforming opacity into lucidity and back again be separated from his opinions on the Balkan Wars, as some of his defenders have argued? Perhaps there is a better, more specific way to put this time-worn question of separating the artist from his art: How did a writer so preoccupied with language, interiority, and individuality become a defender of Serbia in the 1990s?

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Handke’s childhood was a lonely one. He was born in 1942, the son of a Slovenian mother and a German father, a Nazi soldier. Handke didn’t meet his father until adulthood, and his stepfather was a violent alcoholic who terrorized him in his youth. He was raised in rural southern Austria near the Slovenian border, an isolated landscape that runs through his writing.

As a novelist, Handke has sometimes been characterized as an apolitical writer, preoccupied by aesthetic and formal questions (a critic once dispatched his work as “the evil of banality”), but pervading his books is also an antipathy for his homeland—an Austria that he depicts as materialistic, vulgar, and not that far removed from its Nazi past. From the outset, Handke’s novels and plays have been defined by a misanthropy that he, at least, viewed as an antidote to the false sociality of a supposedly liberal Austria and the barely papered-over fascism of its recent history—a deep distrust that made him a youthful rebel in the 1960s and a strange reactionary afterward.

This misanthropy fits perfectly into the political and literary scene in which Handke came of age. Emerging as a prodigy of provocation, he first gained notoriety when he stood up at a 1966 Princeton literary conference and delivered a stinging rebuke to the leading German writers of the time, the so-called Gruppe 47 (which included future Nobel laureates Günter Grass and Heinrich Böll), whom Handke denounced as dull peddlers of “descriptive impotence.” He rejected the project of these socially conscious writers, and in the years to come he devoted his energy to a more abstract investigation of language itself.

Whether or not Handke’s critique was accurate, it heralded a writer whose ruthless focus would be subjectivity itself—what the ego felt, not just what it owed to others—and moreover, a writer eager to nettle the establishment. Instead of “realism,” Handke embraced linguistic virtuosity. His early experimental theater works helped launch his career. The most cited is Offending the Audience, from 1966, a “speak-in” monologue for four performers who address the audience from the stage, describing them and drawing them in and, in the end, targeting them with a torrent of abuse.

Handke’s 1972 novel Short Letter, Long Farewell embraced comic humor as well as disdain. It chronicled an Austrian man on a road trip across the United States, first searching for his estranged wife and then running from her when she threatens to kill him. The narrator eventually ends up at the house of the film director John Ford—a metafictional novelty for its time. A lover of rock and roll and all things unburdened by history, Handke used the US as a screen onto which he could project his fantasies. The dream of a blank-slate nation (which, of course, ignores America’s own genocidal past) would grow into a preoccupation for Handke as he sought to enlarge the boundaries of the self in a world in which he had never felt at home.

Yet even as he wrote about the United States, Handke never really left the Europe of his upbringing. In the 1970s, he produced some of his most accessible work by plumbing his own life story and the relationship between author and text. In the brief but powerful memoir A Sorrow Beyond Dreams, the book for which he is best known among Anglophone readers, Handke describes his mother’s suicide, and it is perhaps his frank admission of grief that allows the reader in beyond the dance of language. Similarly, The Weight of the World (written in the mid-’70s but published in 1977), a kind of daybook that chronicles Handke’s observations during a period of illness, became a West German bestseller. Avoiding political pronouncements, the book is a series of gemlike vignettes of cosmopolitan life, fatherhood, and mortality.

Returning to his mother’s death, and his own family life, may have planted the seed for a new direction at the end of the decade—one focused on Handke’s Slovenian roots. His mother would briefly reappear in the 1979 novel Slow Homecoming, and Slovenia appears prominently in his 1986 novel Repetition.

One of the most careful students of Handke in the 1980s and ’90s was W.G. Sebald, who drew inspiration from Handke’s flaneurs in his own digressive fictions. In an essay on Repetition, Sebald acknowledges his debt and traces the evolution of Handke’s style, considering him as a critical darling who later came to be ignored as his work became more insular. Sebald praised the novel for its alchemical transformation of experience into language but also noted that “in the higher realms, the air is thin and the danger of falling great.” Indeed, Repetition was an early sign of Handke’s descent and the beginning of his fixation on the Balkans.

Repetition’s vagabond is a man named Filip Kobal, who lives in Austria but comes from a family of Slovenian exiles. He journeys south into the country of his heritage and finds a bucolic land outside of time, unscathed by the materialistic corruption of Western society. Kobal rarely mentions that he is also a writer, but after he settles in a village on the rocky karst, he feels a new sense of freedom and imagines that this new life might “bring someone who has time for it an archetype, a primordial form, the essence of some thing.” For Kobal, the Balkans were a place where history couldn’t interfere, and Slovenia and Yugoslavia became for Handke canvases for a new fantasy of a homeland, a stateless state free of difference.

Whether or not the Yugoslavia of the 1980s was this place, by the mid-1990s, the region was far from it. Consumed by brutal wars and genocidal violence, several newly founded states were fighting with each other to establish their desired and ethnically defined borders. Despite or perhaps because of this turn of events, Handke would continue to return to the former Yugoslavia as a more fantastic space in later works like The Moravian Night (2008). He tried to abolish the particulars of place altogether in novels like Absence (1987) and On a Dark Night I Left My Silent House (1997).

As war intensified in the early ’90s, this arch-solipsist stood little chance of playing any mediating role. But he nevertheless wrote about it. In 1995, he traveled to Serbia in a trip recounted in A Journey to the Rivers (subtitled “Justice for Serbia”), a book originally written as a series of articles for the newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung. Travelogue was not so different from the methods Handke had already established, and so the author journeys around Serbia, seeing what he wants to see and not seeing what he doesn’t, indulging in the bucolic pleasures of “a primeval world that appeared as an undiscovered civilization.” The reaction to the book was immediate and intense—it was roundly denounced by critics and literary peers. Contained within the book was a response to his critics, one that took to task what he saw as an anti-Serbian bias in Western media: “What does one know when overwhelming on-line networking produces only information and not the knowledge that can come into being solely through learning, observing and learning?”

While A Journey to the Rivers is studded with the acute details that characterize much of his work, Handke never visits or speaks to any Bosnian Muslims in the book; nor does he attempt to learn about their experiences of the war’s horrors—and only briefly does he wonder if he ought to.

After A Journey to the Rivers, Handke went even further. While he affirmed, in 2006, that the massacre at Srebrenica, when Bosnian Serb forces killed over 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys, was a crime against humanity, he did not use the word “genocide” to describe the event. (He would go on to use the word in a statement years later.) At Milošević’s funeral, Handke waxed rhetorical on his ignorance of Serbian crimes, stating, “I don’t know the truth. But I’m looking. I hear. I feel. I remember. I ask.” Of course, the object of these actions is elegantly omitted, a final perversion of Handke’s late-modernist love of ambiguity. Literary complexity was transformed into the sowing of doubt in the face of overwhelming evidence of war crimes.

In an early play titled Kaspar, Handke tells a story loosely based on the historical case of Kaspar Hauser, a boy raised in a dungeon. The play presents Kaspar in a similar state of sensory deprivation, but instead he is exposed to the noise of contemporary society: a bombardment of mass-media moralism, hygienic advice, and commands to obey. Fearing the same fate, Handke has in the past two decades similarly resisted external viewpoints and sensory intakes that might contradict his most immediate experience and knowledge. But by trusting only his own sentences, he has transformed his resistance to the contemporary world into something far uglier.

The novels that followed Handke’s Balkan controversies have sometimes approached the subject obliquely, though as a novelist Handke holds his cards too close to his chest to ever bluntly state his opinions. However, over time it is possible to notice a drift in his work toward the fantastic, with musings drawn more from the imagination than from any form of direct observation. The Fruit Thief belongs to this group of novels reflecting Handke’s “late style”—not explicitly addressing the Serbian question but offering enough half-clues to keep one thinking about it.

The Fruit Thief is the product of personal experience viewed through a fable’s lens, and the result is a curious hybrid of autofiction and dreamwork. Intermittently over the course of his walk, the narrator tells us the story of the titular thief, a woman named Alexia (for Saint Alexius, we are told, the patron saint of beggars and pilgrims), who is like a daughter to him. After time spent abroad in Siberia, Alexia wanders the small towns and forests of the French “interior,” searching for her mother and encountering a cast of characters so fluid that they melt before our eyes: a pizza delivery boy who gives a speech on the meaning of suicide, an unnamed man in a bar who gives an extended lecture on the botany of the wild hazelnut, and a man roaming the woods looking for his lost house cat, among others. It’s an assuredly laissez-faire approach to storytelling, with a determination to “avoid like the plague and cholera any infection with old stories said to be ‘still relevant today.’” But by seeking not to tell any obviously “relevant” story, The Fruit Thief suggests something more primordial: the writing of a novel as if it were a bedtime story.

This dreamy tolerance for digression aspires to offer readers pure storytelling, a formal flow of surprises that will drive the story, Alice-like, into always-new territory, and there is something almost coy about the extravagance of these rabbit holes, as if Handke takes pleasure in not answering the questions you might pose to him. Still, he can’t help but be drawn back toward justifying himself, albeit in a roundabout way. At the end of The Fruit Thief, Alexia’s father appears, ostensibly to toast the gathering together of a long-separated family: “We stateless people, here and today rid of the state, beyond the reach of the state. All the rest turned into sects—states and churches—and…and… And we? Time refugees, heroes of escape.”

By constructing a total fantasy, Handke can offer up the ideal ending he believes his narrator deserves—a refuge where language is solely an aesthetic tool and no longer socially consequential. This fantasy is at the heart of Handke’s work. Throughout his novels, he dreams of a pure art created by pure exile, an art that can be appreciated for its beauty and strangeness alone. This very inclination to imagine a world outside the world we live in is the weakness of his work as well as its strength. Art may allow us to escape our origins, but it still reflects out into the world, changing it in unpredictable ways.

As is so often the case with “problematic” writers, the sense that their reputation has been damaged is undercut by the feeling that they’ve suffered no repercussions at all. Handke is perhaps the supreme example of this. After publicly complaining about the Nobel, he was more than happy to receive the prize and the financial windfall that accompanied it. But it seems that the criticisms of his position still sting. At a Nobel press conference, Handke exclaimed that a reporter’s question about whether he thought the Srebrenica massacre had happened was “empty and ignorant,” and that he preferred the “anonymous letter with toilet paper inside” that he had previously been sent.

“Can we separate the art from the artist?” is a question that perhaps grows more faded every time it gets asked. But it seems likely that we will continue to ask it—for artists are as likely to be moral monsters as the next person. People are complex and often illogical, and their actions rarely unified. And yet that is, of course, not an entirely satisfactory way to respond to the question either. Don’t the diverse parts of the artist’s self coalesce to create a unique work of art? Sometimes the impulses that can produce great art are all too obvious when, caught out, they prove defective in waking life.

This is true in The Fruit Thief as well. There is something brilliant about it that also seems inextricable from the author’s willful ignorance. Here and there, Handke hints at resisting the attention drain of the ever-accelerating information culture of Western Europe that he so despises: “You have control over the meanwhiles. Don’t let them be taken from you! It’s in the meanwhiles, the in-between stretches, that things happen, take shape, develop, come into being.” But by luxuriating in the meanwhiles, Handke lays claim to a solipsism that finds originality in self-indulgence. Unlike his earlier works, which remain grounded in the brutal truths of the everyday, the hermeticism of The Fruit Thief is less accessible and far more mercurial. Lost in the flow of the narrator’s thoughts, Handke’s novel makes it difficult to know where one idea begins and another ends, and one starts to wonder if that is the point: The novel is, for good and for ill, a study in the act of isolated creativity, the bounty of an artist who has left the world behind for good.

A piece in Quiet Places, a recently expanded collection of Handke’s nonfiction, “Essay on a Mushroom Maniac” offers a striking admission of uncertainty, even a shimmer of repentance—or at least self-awareness. The essay describes a “friend” who becomes obsessed with collecting mushrooms. But as one reads it, one begins to doubt that the narrative is about just this mushroom collector; it reads almost as if Handke is discreetly asking advice “for a friend.” Absorbed in trying to work out a set of patterns for his mushroom gathering—the most promising locations, the best times of year—the friend, a lawyer who defends war criminals, sees his pastime grow into an obsession. After a strange mental lapse, one day he finds himself holding up a mushroom in the courtroom. Handke muses: “Mushroom seeking, and seeking of any kind, caused one’s field of vision to shrink, he asserted, to a mere dot. Blotted out one’s vision altogether.” Handke doesn’t tell his readers to make any further assumptions, but it is hard not to wonder if this is Handke wrestling with his misgivings about his own entrenched opinions.

In a 2016 documentary by Corinna Belz titled Peter Handke: In the Woods, Might Be Late, made about the author before his Nobel victory, we glimpse an image of the author in his home on the outskirts of Paris. Not entirely to our surprise, he goes on long walks, prunes the trees in his garden. He keeps busy, gathering mushrooms. Handke is all eyes and ears in his place of refuge, a romantic figure—one perhaps a little too comfortable. Sequestered in his cozy rooms and his private garden, Handke acts mildly surprised that no journalist has come around to seeing his perspective on Serbia. When Belz tries to push Handke on the years of criticism, he obfuscates, never conceding, but finally admitting that the fallout “haunts” him. Here we still glimpse a Handke who remains stubbornly at a distance from the world around him. Having won everything, why surrender now?