In Poetry’s Church

More than a half century of the Poetry Project

The tone was set early. It was afternoon at the Poetry Project’s New Year’s Day Marathon, the 50th since the event’s debut in 1974. After an hour and a half or so of poems, the day’s topic had come into focus. Sarah Schulman was reading a short essay about Palestine and reaching what felt like a conclusion. “For me, personally, the turning point came when I realized that I would not want to live under occupation for even one day,” Schulman read. “This is what we need to make Americans ask themselves: If they were being occupied and controlled, never had safety, were told what roads to go on, could not travel, could not work or walk where they wanted to without being controlled, had their kids arrested at age 9 for throwing rocks at bullying armed soldiers and then saw their fellows mass-murdered in cycles of repetition—if that was what was imposed on you, wouldn’t you do everything you could to change that? Any honest answer would be yes.”

Hours later, after the audience had heard many calls for a cease-fire, the Palestinian writer and organizer Kaleem Hawa recited a poem called “Maintenance,” set in the Al-Shati refugee camp. Hawa read calmly: “Most staff have long since packed up, save for the enlistees, / snapped and folded into the regulatory matrix, / and then returned to the camp. / Their flip-flops point leftwards when they walk, / their base is the provision of goods and services, / and their tips are the sweat of men.” As Hawa said to me after the reading, “I was trying to chart a different sort of affective course than the poetry of victimhood. The poem is, at once, about the liberation struggle and the infrastructures of colonization.”

The seriousness of solidarity and the power of festive hope have long been central to the Poetry Project. What began in 1966 as a response to a bunch of poets getting kicked out of two cafés has, over its 58 years, become a nonprofit nestled in one of New York’s oldest churches. The Poetry Project is a home for genuinely experimental poetry and performance, a loving refuge that has persisted in a New York where not much else has. (At least none of the bookstores and clubs that I grew up with—other than the Strand—have.)

The members of the Poetry Project are seeking to “change what certain cultural norms are,” its former executive director, Kyle Dacuyan, told me. As the death toll of the Nuseirat massacre climbs and The New York Times continues manufacturing consent for genocide, it may seem that Palestine has no need of poetry from New York. But in a city where cultural institutions are used as moral laundromats for Zionists, changing cultural norms is also vital work. As Schulman posted to a thread on X on February 10: “why [are] so many esteemed cultural institutions in New York, sophisticated national publications, and so many American universities…completely failing to respond to the moral crisis of this bloody slaughter of people in Gaza?”

Other institutions may struggle with their responses to the ongoing genocide, but the Poetry Project has remained resolute: In October, it signed on with the Palestinian Campaign for the Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel, or PACBI. “I think it would be fair to say that it had not been a widely discussed commitment among US cultural institutions prior to that point,” Dacuyan told me. Shiv Kotecha, a member of Writers Against the War on Gaza, reports that since October, at least 176 more organizations have endorsed the PACBI call, including literary magazines, small presses and publishing houses, music labels, podcasts, art galleries, film festivals, and performance venues, among others.

For people engaged in broadcasting the terms of culture, there are poems to be written and labor to be withheld. (See the implosion of Artforum for the latter.) A blend of the material and the spiritual is the political horizon, and this is also poetry’s arena—but it is not grim. I have not been to a musical event with as much energy and heat as the New Year’s Day Marathon in years. I saw the first half in person, and it wasn’t until six hours had passed that I became aware of my body. (I saw the other half via livestream on my laptop; the entire event is now available on the Poetry Project’s YouTube channel. I recommend all of it.) It is hard to think of an event as spontaneous and free of repetition, since so much of what happens doesn’t fall into any one category, and the performers change every five minutes or so. I thought for days about performer Nile Harris, walking up the aisle of the sanctuary with a small speaker and a headset, cleansing the room with a small torrent of feedback, like a spiritual exterminator stalking our baseboards. Legendary dancer Yoshiko Chuma walked the same aisle and jumped into the arms of poet Jim Behrle, wearing the Gumby costume he’d been in all day as he took care of tech duties for the performers.

One moment in particular captures the syncretic jolt of the marathon, and the Poetry Project in general. In the early evening, actor and poet Cecila Gentili introduced a last-minute addition named Emily Allan. After some brief confusion (Gentili didn’t have a bio to introduce her with), Allan performed a song called “Steps to Destruction.” For five minutes, she told a convoluted story of toxic romance that was somehow funnier than it was unpredictable. Imagine LCD Soundsystem’s “Losing My Edge” (same kind of tiny beat) rewritten by Chris Kraus and Patti Harrison, with none of the narration particularly reliable: “I manipulate you into maintaining an intimate relationship with me under the guise of liberated desire and sexual autonomy,” Allan intoned. “We enter a free space of play and association. I tell you that a relationship is simply the erotic thrill of the threat of infidelity. You are impressed by that analysis.” When Allen was done and the crowd cheered, Gentili—impressed and startled all at once—posed our communal question: “Wait… who the fuck are you, Emily?”

Like many creative ventures in cities that are in thrall to the real estate industry, the Poetry Project was itself a miracle, a space emerging out of the chaos and communal energy of a small circle. In 1966, a set of poets who had been gathering at Le Metro and Les Deux Mégots (pun and homage intentional) went through some internecine squabbles and found themselves in need of a new spot for readings. St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, on East 10th Street, was that place. Consecrated in 1799, it’s the second-oldest church building in Manhattan, located on New York’s oldest site of “continuous religious practice.” By the 1960s, it was home to something else, too: Theater Genesis had taken root there, jazz performances were happening during the summer, and poetry readings were common. The church’s reverend, Michael Allen, was active in protests against the war in Vietnam and was generally open to rogue events that might bring locals together.

As reported in Daniel Kane’s All Poets Welcome, the Poetry Project obtained its initial financial support in the form of an unlikely grant. A man named Israel Garver, a federal employee in the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare’s Office of Juvenile Delinquency and Development, was in charge of allocating funds that needed to be disbursed by the end of the fiscal year. He called a friend who taught sociology at the New School, Harry Silverstein, and asked him if he could think of a program that needed the money. Silverstein suggested Judson Church on Washington Square, where a theater and dance community was developing. Howard Moody, the rector at the church, passed the suggestion along to Al Carmines, Judson’s theater director. But Carmines wasn’t interested: “We don’t need sociologists running around in an arts program,” he said. As Kane notes, this missed opportunity provided the opportunity for another: St. Mark’s Church and its various endeavors, including the Poetry Project, got the grant instead and “became a center for politically radical events tied specifically to the oral presentation of poetry.”

Not everyone involved with the Poetry Project agreed about taking the grant—these were poets, after all—but it did help give the developing community a new form of “institutional stability.” That initial cohort included Paul Blackburn, the spiritual leader of the group; Joel Oppenheimer, who had ties to the Black Mountain Poets and who was chosen as the first official director of the program; as well as Carol Bergé, Ted Berrigan, Gregory Corso, Kathleen Fraser, Allen Ginsberg, Gerard Malanga, Peter Orlovsky, Ron Padgett, Aram Saroyan, Tony Towle, and Anne Waldman.

Led by this crew, the Poetry Project set to work. It put on performances and readings; organized benefits for publications like El Corno Emplumado, a Spanish and English experimental-poetry magazine edited by Margaret Randall; and held a memorial for Frank O’Hara after his sudden death. The poets were (almost) unanimous in their protests against the war in Vietnam, which made government funding of any kind unwelcome. Tensions within the group over the federal backing of the project were significant. Ultimately, these conflicts strengthened the project’s political commitments, especially in relation to its role in the neighborhood. “During that hot, early founding period, the Black Panthers had a breakfast kitchen, and the Trotskyites were in the building,” Waldman recalled. “Then you had the Young Lords… it was amazing, mutually supportive, and a kind of hotbed. The whole vision was sort of ‘You do your thing, but don’t mess with my thing.’”

Waldman organized the first New Year’s Day Marathon in 1974. It was called “The Benefit,” running from 8:30 pm to midnight and, just this once, taking place on January 2 rather than the day of. The readers included Patti Smith and Ed Sanders, as well as Helen Adam, Rebecca Brown, Phillip Lopate, Jackson Mac Low, Bernadette Mayer, Lewis Warsh, Rebecca Wright, and Waldman herself.

For the second marathon, in 1975, Smith performed a piece called “Parade,” which you can hear on an album called Sugar, Alcohol, & Meat (an album that features John Ashbery, William S. Burroughs, and John Giorno on the cover). The performance is mesmerizing: Smith switches between sound effects, recitation, and singing, talking about eating crows and pulling out her eyes and teeth like a stand-up comic dissociating. “In the street, the people, they’re livin’ it up! There’s a ticker tape parade!” she declares, sounding more like Art Carney than Frank O’Hara. The first person to play the album for me was Lucy Sante, who saw several of Smith’s early shows. “It’s a spectacular performance,” she told me, “and it’s also a rare artifact of what Patti’s act was like before she formed the Patti Smith Group. She would slide into song form then, here and there, but it alternated with poetry, comedy, asides to the audience—everything sounded as if it was made up on the spot, and no two performances were quite alike.”

Waldman served as the project’s executive director from 1968 to 1978, as a new cohort known as the “younger poets” moved in—a group that included Tom Carey, Maggie Dubris, Bob Holman, Steve Levine, Greg Masters, Eileen Myles, Elinor Nauen, Michael Skolnick, and Rachel Walling. These younger poets found the Poetry Project already locked down in some ways: It was property of the second generation of the New York School. “When we came along,” Myles recalled, “we were all low-key punks who went to CBGB’s and stuff, and we were like ‘Yay!’ when the church’s roof caught fire in 1977.”

But that wasn’t because Myles and the younger poets were not committed to the larger ambitions and aesthetics of the Poetry Project—they just felt the organization itself had to change. They were familiar with the new, multiracial arts scene taking root in a multitude of tiny clubs, galleries, and feminist and queer theaters in the East Village. They were also interested in videotaping the readings, and instead of the legends of Patti Smith and Sam Shepard, they wanted the project to reckon with what was going on at the Pyramid and PS122. New York was also materially different in this period, and the younger poets knew they had to deal with AIDS and homelessness and the many repressions of the Reagan years. And in good dialectical fashion, some five years after the church’s roof was repaired and the building renovated, it was Myles who ended up serving as artistic director from 1984 to 1986; they were also the Poetry Project’s first queer leader. Patricia Spears Jones, who shared the leadership with Myles as program coordinator, was the first woman of color to lead the project.

During the 1980s, various figures became important to the Poetry Project’s operations, especially Bernadette Mayer and Bob Holman. “Bernadette had the very Taurean beer-drinking-earth-mother vibe,” Myles recalled. “She was the project’s first great fundraiser. Bob was the spark and could look wide—he was always getting the necessity for the project to be as diverse as the neighborhood.” A number of the poets were also in bands, like Barbara Barg and Susie Timmons. Richard Elovich and Chris Kraus curated shows at the project in the 1980s; Kraus brought in theater events, while Elovich brought in Karen Finley and Nan Goldin’s The Ballad of Sexual Dependency.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →This period was something like a revival—one of many; they seem to happen at least once a decade—for the Poetry Project. New poets joined; old ones left or moved away. In the early 1980s, the project co-ran a reading series with the Nuyorican Poets Café as a collaboration between Bob Holman, Lois Elaine Griffith and Miguel Algarín, under Bernadette Mayer. In 1982, the Poetry Project newsletter stopped being produced by mimeograph, and throughout the decade poets from the project toured nationally and appeared in similar independent arts spaces. Perhaps against its deeper nature, the Poetry Project had become an institution.

The Poetry Project has carried on into the new millennium. So, too, has its New Year’s Day marathons. In 2018, Kyle Dacuyan, a poet and former PEN America staffer, was appointed the project’s executive director. In his five-year tenure, Dacuyan significantly increased fundraising and doubled the size of the staff. He recently passed the torch to interim director Nicole Wallace, and along with program director Laura Henriksen, editorial director Kay Gabriel, and countless others, Wallace has continued to link experimental arts programming with the work of building and maintaining an oppositional liberation-oriented community—joining political and cultural fronts in a shared central meeting place.

There are few communities as fond of infighting as New York’s literary set, but somehow the Poetry Project seems to transcend this fractiousness. Spending New Year’s Day at the project was a true blessing. Opening its doors to any who want to join and reinvigorating its role from the Vietnam era onward as an anti-war cultural organization, the Poetry Project serves the function of a “church”—its colloquial name in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s. The project makes it possible for people engaged in the business of changing everything to cohere in a shared and meaningful sense of the world at regular intervals. Its new cohorts, Myles told me, have helped to make it “a new thing. It’s more queer and trans of color in a way that the Poetry Project has always been, but not in such a front-and-center way. It’s radical again, and it always was.” Wallace adds: “I think there’s a care and desire to keep that scrappy, freaky spirit going.”

In February, Cecila Gentili passed away unexpectedly. Her one-hour slot as marathon host was one of her final public appearances. Her funeral, held several weeks later at St. Patrick’s Cathedral, felt like another ingathering of the Poetry Project spirit. At the service, editorial director Kay Gabriel said, “Everyone served extreme cunt,” which seems the right description for a day of drag and Catholicism (if there is any difference between the two). But Gabriel also provided an answer to the question of why the Poetry Project keeps on going. When talking about what Gentili brought to the project, Gabriel mentioned her “ability to make people convene for a serious purpose from the point of view of having a joyful orientation towards life, in which people who would not have recognized each other otherwise could meet each other and learn and become something else through each other.”

At the beginning of April, I walked to the Poetry Project’s home in lower Manhattan, going north on Second Avenue, up from Second Street to 10th Street. There were very few places, aside from the restaurant Veselka (an East Village landmark) and the Ukrainian National Home, that had been there in my youth, when I wrote poetry like a headless hose, and yet St. Mark’s Church and the Poetry Project were still among them.

On that evening, I found myself sitting in the parish hall of the church, one among many in a standing-room crowd assembled for Ann Rower’s launch of the revised version of her If You’re a Girl, first issued by Semiotext(e) in 1990. The readers included Richard Hell, Kate Valk, and Rower herself, making her 30th appearance at the project (her first was in 1978). It was vastly moving for so many reasons. Here was a feeling rare in a city in which almost everything gets sold to the highest bidder: a sense of continuity and history, but as important, a sense of community. We are all looking for that in New York—that feeling when, as Myles described it, “suddenly, you were standing there, and you were with your people, and you knew why you were there.” If these connections go missing elsewhere in the city, there is one very specific reason they are found at the Poetry Project. “If it’s a new accident that poetry holds that space, then that’s just marvelous, because all it is language,” Myles said. “It’s language not owned by anybody. You can’t sell poetry, but you walk through it and you hold it and you remember it and you’re getting on the train and you think about it.”

More from The Nation

“The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy “The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy

The new show from the creators of The Office reminds us that their comedic style does now work in every “workplace in the world.”

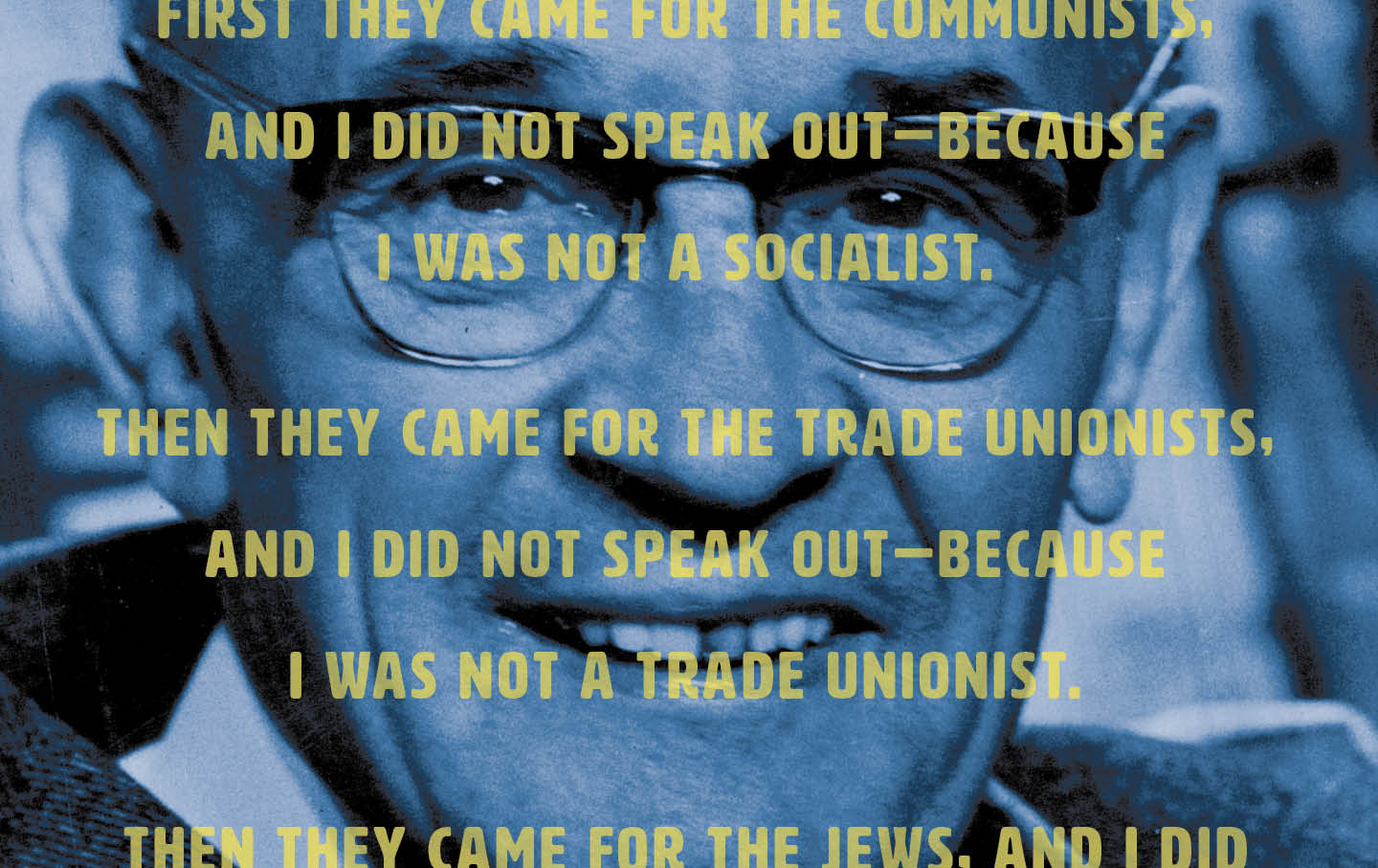

The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…” The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…”

In his celebrated mea culpa, the German pastor Martin Niemöller blamed his failure to speak out against the Nazis on indifference. Was that the whole reason?

The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme” The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme”

Josh Safdie’s first solo effort, an antic sports movie, revels in a darker side of the American dream.

John Updike, Letter Writer John Updike, Letter Writer

A brilliant prose stylist, confident, amiable, and wonderfully lucid when talking about other people’s problems, Updike rarely confessed or confronted his own.

TikTok’s Incomplete Story TikTok’s Incomplete Story

The company has transformed the very nature of social media, and in the process it has mutated as well—from tech unicorn to geopolitical chesspiece.