If the Left Doesn’t Channel Populist Resentment, We Know Who Will

What tone-deaf liberals can’t hear in Rich Men North of Richmond.

The liberal commentariat is miffed. Oliver Anthony, a white down-and-out former mill worker, broke the Internet with a populist country tune called “Rich Men North of Richmond” recorded on his land in Farmville, Va. Folks of all races, from the right, left, and center, are singing its praises.

I’ve watched dozens of reaction videos, many of them by Black music critics visibly moved, sometimes to tears, by Anthony’s extremely relatable lament—“selling my soul, working all day, overtime hours for bullshit pay,” while the powers that be kick us all down, “people like me, people like you.”

After decrying workplace exploitation, Anthony goes after a political establishment whose only use for the working class is to tax and control them while letting inflation, hunger, and greed run rampant. It is the song of a man who feels sad, angry, beaten-down, and all but hopeless. That is to say, it is the ballad of 2023 America.

Related

But many left-leaning commentators weren’t moved. In the pages of The Nation, The Washington Post, Slate, and elsewhere, they argue that the song carries a reactionary, right-wing message. They cite lyrics that demonize overweight people who spend their food stamps on junk food. They take aim at one line that obliquely references Jeffrey Epstein and jump to the conclusion that Anthony is a Q-Anon/MAGA nutjob. And they note that right-wing bomb throwers like Matt Walsh, Kari Lake, and Marjorie Taylor Greene are promoting the song.

They have a point. The trope of the lazy welfare cheat has been a staple of blame-the-victim, anti-government rhetoric for decades. And right-wing politicians and influencers do have a nasty habit of donning the mantle of working-class crusader while serving the rich and powerful.

But here’s what I believe liberal critics are missing when they focus on the song’s discordant notes: People are working “overtime hours for bullshit pay.” There are “folks in the street with nothing to eat.” And working- and middle-class taxpayers are getting squeezed, because neither party is willing to raise taxes on the rich. Meanwhile, an out-of-touch Democratic establishment is telling us that, thanks to Bidenomics, the economy is thriving, the implication being that there’s little cause for complaint. If we want to reach the people who have made this song their anthem, we have to spend more time hearing what they, and their music, have to say, and less time yucking on their yum.

It’s true that Anthony hits a sour note when he dishes on welfare recipients; it’s easier to notice and judge the choices of someone at the grocery store than it is to observe the Amazons and KFCs and opioid peddlers picking our pockets and wrecking our bodies. Right-wing propaganda takes advantage of the human brain’s tendency to focus on what’s right in front of us and extrapolate sweeping generalizations. We need to relentlessly put forward a counternarrative that holds the real culprits accountable.

The song’s fans are fed up and ready for change, but if the only change on offer is slashing the welfare rolls or sealing the border or banning critical race theory, then that’s what many of them will go with. Others will surrender to apathy and cynicism, convinced that no one in the political class truly cares about them. Populist ferment requires yeast, and right now the left isn’t supplying it.

I asked John Russell for his take on the song. Russell is a bartender in West Virginia with a Substack about class politics called The Holler. Coincidentally, Russell, like Anthony, got famous a couple of weeks ago, after he went to a Trump rally in Erie, Pa., to see if he could overcome what he calls the “engineered division” of the working class into right and left. To the amazement of many liberals, he got Trump rally-goers talking about monopolies, corruption, and corporate greed.

Russell cautions liberals against throwing the baby out with the bathwater just because some of the lyrics assign misplaced blame. “The working class’s reaction is a big fat ‘yes,’ and everyone who wants a working-class movement should pay attention to it,” he told me. Were he in command of the Democratic Party, he’d make sure candidates show up in all the forgotten places and keep reminding folks that it’s the rich men north of Richmond who are ruining their lives.

Russell is right. The song is an opportunity to take stock of our own shortcomings instead of restating what we already know about how cruel and manipulative right-wing propaganda is. It’s also an opportunity to take a hard look in the mirror: Liberals have a habit of denigrating rural and working-class people’s tastes and lifestyles. Their scorning and scolding have antagonized millions of Americans who look to Trump, as resenter in chief, to retaliate.

What Anthony’s fans hear us saying is: Don’t like what you like. We’ll tell you what’s worthy of your esteem.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →I believe that this kind of elitist condescension is a big reason working-class voters (and not just white ones) increasingly vote Republican or stay home. Many of the tweets in response to Rolling Stone’s negative review of the song reveal widespread anti-elite sentiment:

@HocDolliday makes the point I want to end on here. The negative reaction to this song is an unforced error reminscent of the “basket of deplorables” gaffe that likely cost Hillary Clinton Pennsylvania and the presidency. It prompts working people to resent us and to look to faux-populist charlatans like Trump who at least pretend to respect them. If people think voting against the rich men of Richmond means voting Republican, we’re in serious trouble.

More from The Nation

“The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy “The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy

The new show from the creators of The Office reminds us that their comedic style does now work in every “workplace in the world.”

The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…” The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…”

In his celebrated mea culpa, the German pastor Martin Niemöller blamed his failure to speak out against the Nazis on indifference. Was that the whole reason?

John Updike, Letter Writer John Updike, Letter Writer

A brilliant prose stylist, confident, amiable, and wonderfully lucid when talking about other people’s problems, Updike rarely confessed or confronted his own.

The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme” The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme”

Josh Safdie’s first solo effort, an antic sports movie, revels in a darker side of the American dream.

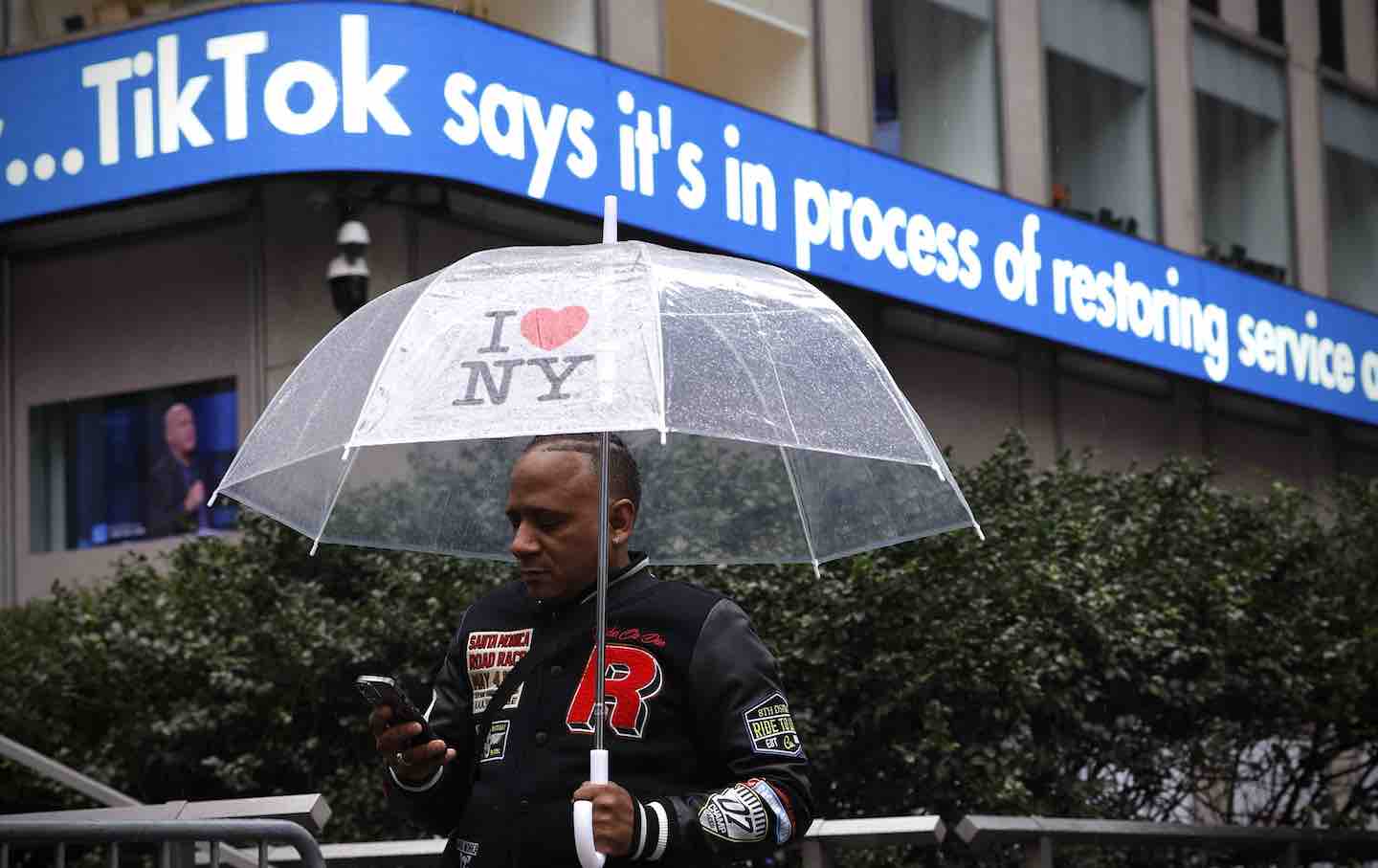

TikTok’s Incomplete Story TikTok’s Incomplete Story

The company has transformed the very nature of social media, and in the process it has mutated as well—from tech unicorn to geopolitical chesspiece.