Robert Eggers’s Nosferatu Is a Modern Gothic Triumph

Robert Eggers’s “Nosferatu” Is a Modern Gothic Triumph

The latest adaptation of the silent film classic evokes anxieties at once eternal and contemporary, using one of horror’s ur-texts to dissect race, sex, and power.

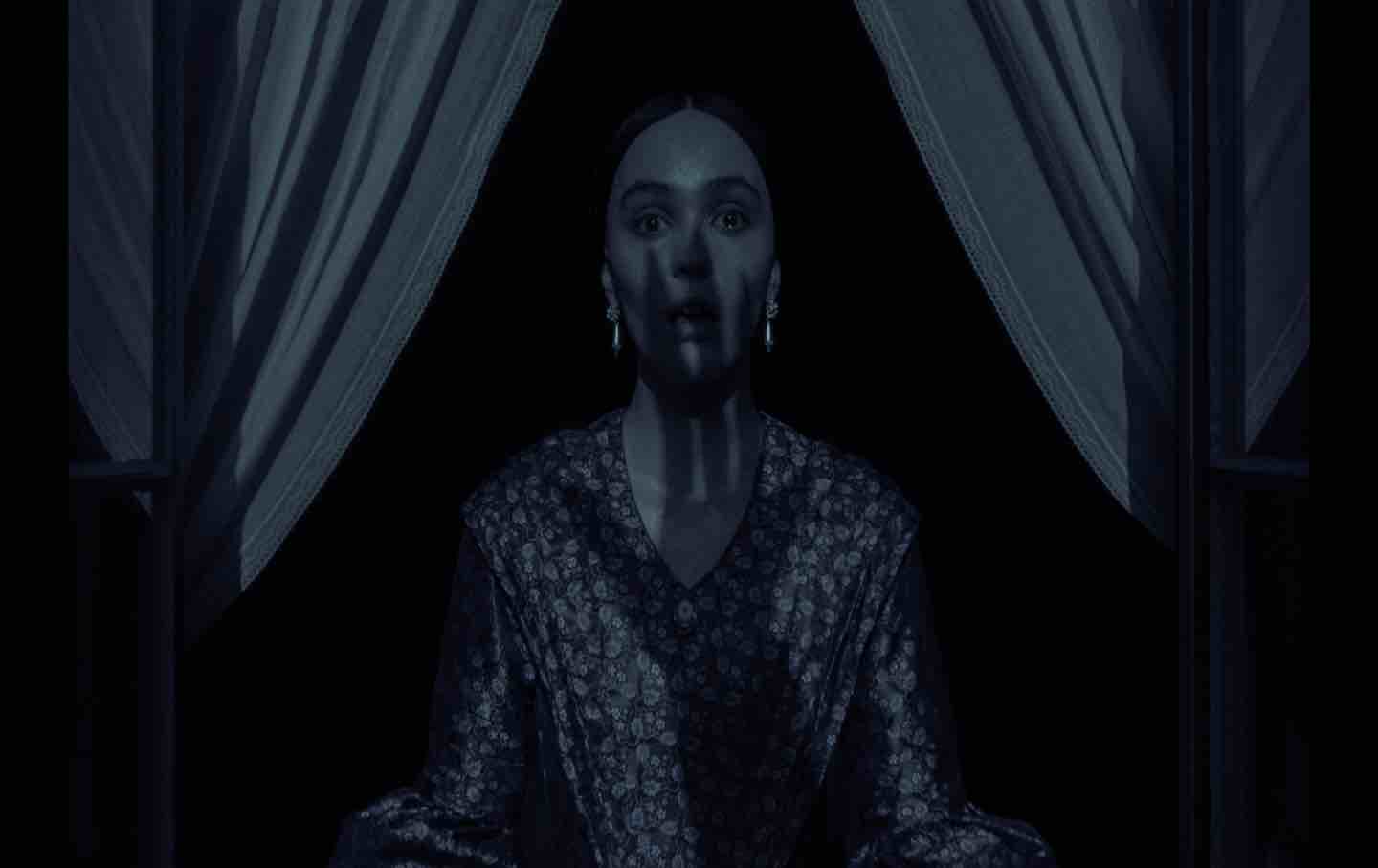

Lily-Rose Depp as Ellen Hutter in director Robert Eggers’s Nosferatu.

(Aidan Monaghan / Focus Features)

Somewhere in the overcast German town of Wisborg, our weeping protagonist, Ellen (Lily-Rose Depp), emerges from the shadowy corners of her bedroom. Enveloped in an aching loneliness as dense as the sheet of darkness that blankets her, she cries out to some astral plane for companionship. “Spirit of any celestial sphere,” she sobs, hands clasped prayerfully, “come to me!” The response, far from empyreal, pierces her mind and commands her flesh with a rasping whisper. She opens her eyes to reveal a vacant gaze as she drifts, mesmerized, toward her balcony where Count Orlok (Bill Skarsgård) has cast his silhouette upon a pair of billowing curtains. “And shall you be one with me ever-eternally?” he hisses, drawing her into the lush courtyard below. By the time Ellen, unwittingly or otherwise, swears herself to him, this story as we commonly know it has not quite begun, but her descent is complete. Like Eve in her garden or Persephone in her meadow, Ellen’s encounter with the devil is an encounter with the murkier, more concealed depths of nature—or, to put it crudely, sex. The critic Robin Wood once observed that “nature” is the real subject of F.W. Murnau’s 1922 silent film classic Nosferatu, and Robert Eggers’s new adaptation remains most faithful to the original in this sense. Lying under an ornate arch of white roses, Ellen is seized by the first of the feverish nocturnal convulsions that betray Orlok’s presence.

Years later, we find her newly married to an ambitious estate agent, Thomas Hutter (Nicholas Hoult). He appears to be a doting, if fatally myopic, husband; the couple are in love, but he does not understand her. Ellen is still vexed by painful childhood memories and disturbing visions: “But I’d never been so happy as that moment,” she recalls tearfully, “as I held hands with Death!” Thomas—with more traditional ideas (less emotional, more material) about providing for her—dismisses these dreams.

At the behest of his employer, Herr Knock (Simon McBurney), Thomas heads for the Carpathians to negotiate in person with the firm’s mysterious new client: none other than Orlok, who wishes to secure a residence in Wisborg. Ahead of his trip, Thomas leaves Ellen with the Hardings, Anna (Emma Corrin) and Friedrich (Aaron Taylor-Johnson), their much wealthier friends. In the Hardings, the Hutters find bitter reflections of their own presumed inadequacies. Friedrich is a successful shipyard owner, and Thomas aspires to his prosperity, while the charming, regal Anna models an impossible performance of traditional femininity—gracious mother, agreeable wife—for the wan Ellen, so often overtaken by somber or passionate moods.

As Thomas breaches the misty woodlands along the snowy, alpine horizon of Transylvania, curious happenings trail him. At the inn where he briefly sojourns, the Romani community there advises him not to venture further. When his horse abandons him, Thomas resumes the journey on foot until a driverless carriage suddenly appears to convey him to Castle Orlok. There, he finally meets his fearsome host, an imperious nobleman with putrid features and a husky baritone. Thomas immediately crumbles in terror and never quite recovers. He cannot refrain from trembling during their nightly summits, and the count always disappears in the daytime. There exists an implacable sense of Orlok’s malignance even before Thomas discovers him sleeping naked in a coffin. More bizarrely, the young man finds himself eerily incapacitated. He awakens with little memory of the night before and bite marks on his chest. But Orlok refuses to let him leave.

Back in Wisborg, Ellen is also struck by a peculiar somnambulism. Beleaguered by frightening seizures, her limbs inhumanly bent and outstretched, she prophesies—ventriloquized by some otherworldly force—in hoarse, unearthly, even delighted tones, “He is coming!” The Hardings entreat the counsel of Dr. Sievers (Ralph Ineson), whose conventional knowledge proves no match for Ellen’s ineffable malady. So Sievers turns to his former professor, the eccentric occultist Albin Eberhart Von Franz (Willem Dafoe), the only one who can name the dreadful creature they face: the plague-bringer, “the vampyr Nosferatu.”

Perhaps no contemporary filmmaker is better suited for this lofty revival than Eggers, already inclined to trace the lineage of the Gothic project and, invariably, the ongoing anxieties this mode is uniquely disposed to express. In that way, his period portraits inevitably divulge more about the workings of the modern world than many contemporary films care to say. Where Eggers departs from his looming progenitors (Werner Herzog and Francis Ford Coppola among them) is by locating this familiar tale, based on the Bram Stoker novel Dracula, in the perspective of Ellen, the doomed young bride who runs afoul of Orlok’s lecherous designs. This pivot propels us into the very core of Gothic history and the politics that have shaped the genre from its literary inception.

Since first viewing it when he was 9 years old, Eggers has nursed a primal affection for Murnau’s Nosferatu. He codirected and starred as the count in his high school stage production of the tale, a rendition that caught the eye of a local theater director, who invited Eggers to professionally restage the play for his company. He would devote his subsequent years to cinema in the image of his Gothic and German Expressionist icons: His debut feature, The Witch (2015), suggested an author with a clarity of vision, fastidious in matters of historical detail. At length, Eggers would prove himself a reliable craftsman with a healthy sense of irreverence (fart jokes, devilish goats, etc.) and an affinity for historical re-creation. Here again, in Nosferatu, we find all the signature embellishments: the masterful atmosphere, the absurdist humor, the scrupulous research, the visual extravagance, the stock supporting cast (Ineson and Dafoe reunite with the director for the third time), lovingly measured with a broad fidelity to the material.

Eggers’s longtime collaborator Jarin Blaschke lends a stately dimension with his grisaille cinematography: sepia-veiled scenes in the Hardings’ lavish mansion reminiscent of Victorian portraiture; dusky long takes of Thomas waiting in the barren, snow-crested avenues outside Castle Orlok. Each shot charts its generic heritage, from Carl Theodor Dreyer to Jack Clayton. Naturally, the film contains an ancestral sprawl that attests to its source material’s enduring eloquence: Hoult starred in Renfield (2023) as the count’s mononymous minion, played here by McBurney with relish; in 2000’s Shadow of the Vampire, Dafoe (the veteran of no fewer than four other vampire films) played the actor Max Schreck, who portrayed Orlok in the original Nosferatu. In particular, Depp’s intensely physical performance recalls a long lineage, evoking forebears Greta Schröder and Isabelle Adjani, but also the likes of Linda Blair in The Exorcist (1973). In this cinematic genealogy of “mad” women—their bodies driven, supernaturally or otherwise, to articulate their psychosexual unrest—we discover the remnants of a centuries-old belletristic tradition that Eggers artfully embraces. It is this framework—in which the sexual, nationalist, and racialized dimensions of the Gothic so richly intersect—that animates his film.

Stoker’s novel already boasted a striking genetic resemblance to what was retroactively christened the Female Gothic, literature that gave voice to the waking distress that plagued women: forced marriage, femicide, rape, incest, and the trauma of childbirth. Although Dracula is not usually counted within the genre’s ranks, Stoker does borrow its central xenophobic arc (see The Italian, Zofloya, Wuthering Heights, etc.): an orphaned heroine sexually pursued by a decadent, aristocratic man, often a racialized foreigner who seeks (by force or seduction) to confine her in his ivy-coiled estate. This literary connection is instructive because it provides a grammar for understanding the gendered slippages of Stoker’s tale and Eggers’s retelling, organized around a woman’s point of view.

Notably, Eggers’s (and Stoker’s) narrative relies on an inversion: Thomas’s internment at Castle Orlok resembles the domestic captivity and sexual danger that defined the subgenre (and women’s lives). For the first third of the film, he functions as the archetypal Female Gothic heroine—trapped and wandering the castle’s sepulchral corridors, slipping into forbidden chambers where he fails to plunge a stake into the count’s chest. The young bridegroom’s impotence shadows his eventual reunion with Ellen, for the lovers now share a strange twinship, also marked by the way Thomas’s mysterious convalescence—mired in sweating nightmares of Orlok—doubles her own. Later, furious and likely possessed, Ellen cruelly recalls that Orlok “told” her “how [Thomas] fell into his arms like a swooning lily of a woman!” The scene, pure Eggers flourish, culminates in urgent, frenzied sex, at once an anxious exercise in masculinity for Thomas and a willful performance of submission for Ellen.

The Female Gothic novel achieved such popularity among bourgeois women in the 18th and 19th centuries—largely written, as this fiction was, by bourgeois women themselves—because it cataloged their own ambivalent relationship to the domestic: torn between a fear of entrapment and their erotic and classed investment in their persecutors. We know that Ellen is compelled to smother her voracity—the fount of disavowal from which her inner tumult certainly springs—and can reasonably discern that her marriage to Thomas offers a “safe” place for her to express her desires, but one not quite free from her intolerable, abiding shame. “He is my melancholy!” she confesses to her horrified husband.

The figure of the vampire expertly summons a labyrinth of metaphor, including this sexual and gendered defiance. (Biographers report that Stoker began writing Dracula around the time his childhood acquaintance, former romantic rival, and fellow Irishman Oscar Wilde was convicted of sodomy; several scholars speculate that the inspiration for Dracula himself, at least in part, was the disgraced, imprisoned writer.) But the vampire is, perhaps above all for Stoker, a monstrous interloper that imperils the “home”—marriage, community, nation—which (white) women remain obliged to symbolize.

An unrecognizable Skarsgård renders Orlok in a chilling, transformative performance, his voice a deep, thunderous rumble cloaked in a Slavic-tinged accent, each word a thick snarl between gasps of wheezing, labored breathing. Eggers sensibly strives to avoid the antisemitism that has troubled the count from his provenance: The design of Skarsgård’s Orlok respectfully nods to the bat-like villain animated by Schreck but skirts the more flamboyant elements of racial caricature. Now he appears closer to a decomposing, mustachioed corpse, pallid and anemic, with stringy wisps of hair slicked to the side of his bulbous skull. But Orlok’s ethnic difference remains integral to his threat: He communicates extensively in Dacian, a long-dead Romanian tongue, and Thomas’s Transylvanian expedition is, from the beginning, a collision both with the racial other (in his dealings with the count as well as the local Romani) and the vampire’s wanton sexuality: “I am an appetite, nothing more,” Orlok tells Ellen. Moreover, his illicit voyage to Wisborg—flanked by rats, of course—promises a blood contamination that its denizens cannot survive.

Consider, too, the bare skeleton of the vampire’s enterprise: to conquer the Protestant West, prostrate the men, and sexually subjugate their women; in short, the very campaign of organized violence—complete with disease-spreading—that these same parasitic nations employed in their colonies. The film falls comfortably, then, within the thematic perimeter of Eggers’s work. At least twice now, the director has charged himself with the nature of empire, and as such the ugly entanglement of whiteness, sex, and power.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The Puritan family at the center of The Witch, a portrait of the nation’s perverse individualist origins, so fear spiritual pollution (including “Indian magic”) that they alienate themselves in the woods, away from their fellow Puritans, who fail to equal their religious vigor. They cannot help but perish, remote from humanity outside and within, as their eldest daughter becomes for them an incarnation of sexual deviance. Eggers is on record about the reservations that nearly prevented his making The Northman (2022), loosely based on the same Norse legend as Hamlet. “The macho stereotype of that history,” he told The Observer, “along with, you know, the right-wing misappropriation of Viking culture, made me sort of allergic to it, and I just never wanted to go there.” Some critics question whether the filmmaker successfully cleaved this narrative from the vapid clutches of white supremacist fancy, but the feudal conflicts are there for those who wish to see them, and in time the hero learns that his quest to avenge his slain king father has been in service to “a proud, lust-stained slaver.”

Of course, any foray into the Gothic must embody these questions, for its very scaffolding gives way to these themes. In the end, Orlok is defeated: Much like the women he so determinedly preys upon, he, too, discovers in the domestic a lethal trap. In the finale, we have yet another inversion, this time of the film’s prologue, as Ellen lures the vampire into a simulation of a marriage scene, a fulfillment of their deathly covenant. The final shot is a visual consummation of her tragedy: The seemingly erotic convulsions that disturb the men around her so much that they resolve to tie her to the bed is the kind of arch symbolism that, like mass infection, collapses the centuries. But then Eggers understands nothing so well as the Female Gothic’s supreme diagnosis—that the traumatized, or those who shut their eyes to the past, are compelled to repeat the repressed as contemporary experience. Perhaps Nosferatu survives in every age because we, too, are still replaying its guiding tensions.

More from The Nation

“The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy “The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy

The new show from the creators of The Office reminds us that their comedic style does now work in every “workplace in the world.”

The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…” The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…”

In his celebrated mea culpa, the German pastor Martin Niemöller blamed his failure to speak out against the Nazis on indifference. Was that the whole reason?

The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme” The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme”

Josh Safdie’s first solo effort, an antic sports movie, revels in a darker side of the American dream.

John Updike, Letter Writer John Updike, Letter Writer

A brilliant prose stylist, confident, amiable, and wonderfully lucid when talking about other people’s problems, Updike rarely confessed or confronted his own.

TikTok’s Incomplete Story TikTok’s Incomplete Story

The company has transformed the very nature of social media, and in the process it has mutated as well—from tech unicorn to geopolitical chesspiece.