Rumaan Alam’s Haves and Have-Nots

With his latest novel, Entitlement, he asks: Can wealth inequality make you lose your mind?

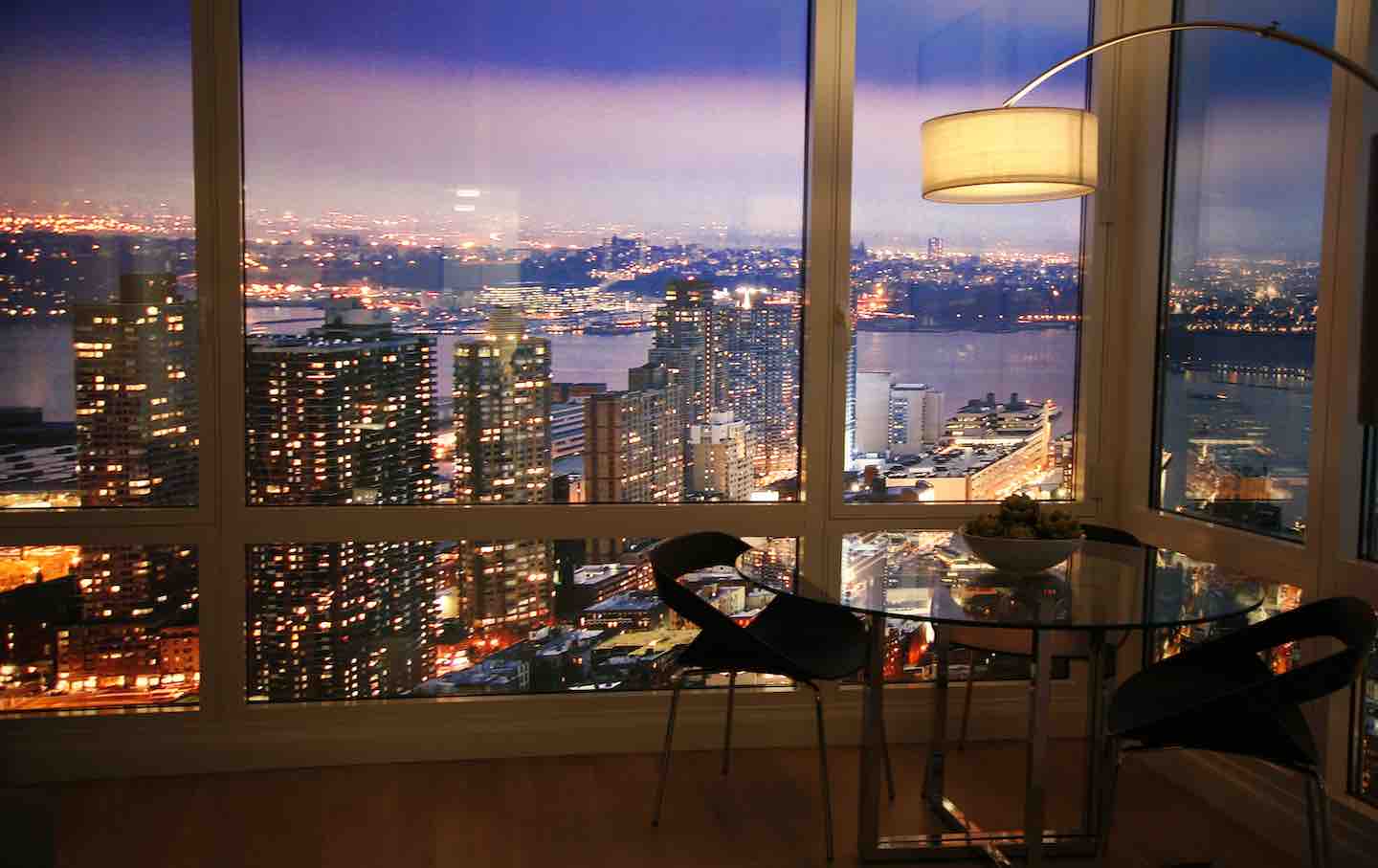

An interior view of a model condominium at the sales center for the Platinum luxury condominiums in New York City, 2008.

(Amy Sussman / Getty Images)

Over the past decade, Rumaan Alam has established himself as a gently wry chronicler of New York’s upwardly mobile classes—as well as a vigilant observer of their homes. In his 2016 debut, Rich and Pretty, we get the story of best friends Sarah and Lauren, who are continually drawn back to the ivy-covered townhouse that Sarah’s family owns on East 36th Street, where the pair spent many adolescent afternoons. Its capacious layout—foyer, living room, dining room, library, basement kitchen, ample backyard, roof deck, nanny apartment, multiple bedrooms—is rendered with a precision that would make a broker proud. In Leave the World Behind, Alam’s 2020 thriller, we follow the travails of two families menaced by a coyly unspecified disaster event while holed up in a Hamptons vacation home whose immaculate finishes are lovingly inventoried—from the French doors to the marble countertops to the wood floors reclaimed from a defunct cotton mill.

Books in review

Entitlement

Buy this bookIn Alam’s new novel, Entitlement, real estate is once again prevalent, acting as a shorthand for the divergent material circumstances among a group of friends, family, and colleagues. Of the many different apartments it depicts, from Bedford Stuyvesant to the Upper West Side, two in particular loom large. The first is a modest one-bedroom on 29th Street in Manhattan that the novel’s protagonist, Brooke Orr, becomes fixated on buying despite lacking the means to do so. The second—a minimalist masterpiece overlooking Central Park from what can only be Billionaires’ Row—belongs to her boss, the newly minted philanthropist Asher Jaffee.

It’s clear that Alam, whose own house has been featured in multiple design publications, takes a certain amount of pleasure in building this fictional portfolio. (“I don’t care about sports, unless you count real estate,” he once told Curbed.) But his portraits are more than merely decorative: In his novels, as in life, homes are furnished with symbolic significance. Rich and Pretty’s townhouse is a portal to the past that grounds a decades-long relationship between two women who have known each other since middle school. The well-appointed vacation rental in Leave the World Behind is a reminder to one Brooklyn couple of all that their upper-middle-class striving has yet to achieve, a symbol for another couple of all they have overcome, and later a fortress against the violent breakdown of society.

There’s always been a measure of class anxiety in Alam’s work, but in Entitlement, the divides between the haves and the have-nots are starker and more unsettling. In the novel, Asher Jaffee’s pristine aerie represents the ultimate privilege of inexhaustible wealth: the ability to withdraw from society while acting upon it as a god. The 29th Street apartment might be humble by comparison, but Brooke Orr’s hopes for it are not. To her, it’s not just a promise of stability but a talisman that could solve the riddle of her life. It might fulfill her quest for purpose, make her “the person she meant to be.”

From the start of Entitlement, it is clear that Brooke and Asher are mismatched in ways that go well beyond their respective net worths: Brooke is a thirtysomething Black woman, Asher an octogenarian white man. But difference is no impediment to the blossoming of their professional relationship, which begins shortly after Brooke is hired as a program coordinator at the Asher and Carol Jaffee Foundation, a lean, start-up-like nonprofit designed to dispense the bulk of Asher’s $3.7 billion fortune before he shuffles off this mortal coil. Asher’s interest in Brooke is piqued when she tells him about her dispiriting experience teaching at a Bronx charter school (they cut the arts program so that the children might learn to code). It is then cemented when she tries to refuse a reimbursement check for a lunch meeting that he issues her from his personal account. “I see something in you,” Asher tells Brooke. “Maybe a protégé.” He charges her with finding a youth arts organization the foundation might support.

Brooke is energized by her boss’s belief, but the mission of changing others’ lives with an enormous financial gift soon becomes entangled with her mission to change her own. “Good things were possible for the world, and most importantly, good things were possible for herself,” the novel quips (the narration is in a third-person voice that largely stays close to Brooke’s consciousness, with occasional forays into other perspectives). As Brooke begins to entwine her life more and more with Asher’s, the gulf between their lifestyles and identities becomes more acute, but at the same time, in Brooke’s increasingly delusional eyes, more surmountable. She comes to believe that Asher—his serenely confident business philosophy and, later, the man himself—is the key to realizing her homeowner fantasies.

Entitlement is not only about class and real estate but also about a particular moment in US history. Taking place in the summer of 2014, amid “the good luck of a boring moment in the world’s long history, Obama’s placid America,” it is a barbed requiem for the dream of a multiracial progressive future that Barack Obama’s election seemed to embody and that had not yet entirely curdled into the reactionary backlash that would sweep Donald Trump into the White House for the first time.

Brooke’s own work puts this dream at its center. While Asher does not make this explicit, Brooke interprets her assignment at his foundation as supporting the artistic development of not just any children but a specific set of them: “Black kids with Black problems.” Eager to please and to prove herself, she discovers a humble operation in Brooklyn teaching children African music and dance out of a damp church basement, which she encourages Asher to support. The woman who runs it, Ghalyela Jefferson, is a beatific figure who is willing to do anything for her students—except selling them out. At first, Ghalyela is wary of Brooke and any outside influence, but eventually Brooke is able to persuade her to accept a still-hypothetical gift from the foundation. It turns out that the two of them want the same thing—real estate—though for very different reasons. The older woman hopes to build a permanent home for her students in a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood that threatens to displace them. Brooke’s desires are motivated by more personal feelings: a sense that she’s been denied prerogatives that should rightfully be hers.

Because Brooke’s own ascension up the property ladder is her underlying motivation when it comes to her philanthropic work, her relationship with Ghalyela, and even with her own identity as a Black woman, ranges from ambivalent to mercenary. Though her two best friends, Matthew and Kim, are Black, Brooke resents the solidaristic overtures of most of the other Black people she encounters in the book—a young city council candidate, a panhandler, Asher’s driver—whom she sees as either users or impediments to her individual success. “The power of tribe,” she thinks disdainfully after meeting the city council candidate, a woman named Alissa McDonald. “Even if they looked one way, they were nothing alike.” When Brooke senses that the presumption of sisterhood might be an advantage to her, however, she is happy to capitalize on it, as she does with Ghalyela and, later, a mortgage underwriter at Chase Bank.

Brooke’s relationship to her identity is complicated by another matter: She is the adopted daughter of a white single mother. Growing up, Alam writes, “Brooke spent most of her time with white people, who never discussed the allegiance of race, because they did not need to.” That her mother, Maggie, and her brother, Alex—who is also adopted, but white—are close causes Brooke to sometimes get a “familiar feeling, ugly, best suppressed,” one that she disguises “with a veneer of smile, nod, downturned face.”

While Brooke’s uncertainties about who she is remain unresolved, so, too, does her relationship to the rich: At times, she wants to emulate Asher’s sense of entitlement, his ability to “demand something from the world. Demand the best.” But at other times, she seems to register, if distantly, that there is something monstrous in this orientation toward the world. When it comes to excelling at work and, above all, securing the 29th Street apartment, Brooke has a surfeit of desire: “She was in a state that either no one else could see or everyone else turned away from as though she were again a two-year-old with her hand down her pants. She needed; she wanted; she coveted. She felt itchy and on fire.” Her attempts to manifest what she wants through sheer determination risk alienating her from her loved ones and, ultimately, lead her to commit fraud.

This happens because, while Brooke may be working for a billionaire, she is not one herself. In an attempt to secure her mortgage, she forges a proof-of-income letter to inflate her salary and uses her corporate credit card to invest in a luxury capsule wardrobe, complete with Christian Louboutin heels. Brooke sees this illicit shopping spree as a token of faith in her own future: “If she couldn’t be rich, she could at least possess some of what rich people did. To participate in this world would get her nearer to that apartment.” When her plan to increase her karmic balance by securing a significant donation for Ghalyela’s school fails to pan out, Brooke persuades herself that all is not lost: Asher will purchase the home for her himself.

There is the tantalizing suggestion, as Entitlement progresses, that the proximity to obscene wealth one can never hope to attain is enough to drive a person insane. Alam’s novels have often focused on the narcissism of small differences between the truly affluent and the merely well-off, a perspective that Brooke’s friend Matthew gives voice to here: “The people who are obsessed with money aren’t the rich who have it or the poor who don’t. They’re us. They’re the big middle, it’s all the rest of us, because we know what money can do. We know how we’ll never get our hands on it, but we know it could make us free.” Entitlement raises the stakes of this comparison by making Brooke’s foil a man rich enough to reshape swaths of society according to his own whims. The gap between Asher and Brooke is no matter of small differences.

Brooke is constantly reminded of this gap throughout the novel. After gaining Asher’s confidence and temporary access to the privileges he takes for granted—a standing table at Jean-Georges, the view of the city from his chauffeured Bentley—she begins to feel as though she has glimpsed an alternate reality, a promised land outside her reach. “There are men with this much money,” Brooke tells Matthew, “and it’s not that they control the world. They’ve defeated it. They’ve left it. They live somewhere above the rest of us, and we spend our days not knowing this because if we did we would all lose our minds.”

Yet Brooke does know this, and it eventually leads her to a more belligerent conclusion: “I think it’s good to look right at it…. To say fuck that. To say that we will do what we have to do. Because we will do what we must.” Her use of the word “we” might suggest that this is a moment of political radicalization, one in which her bitterness is rerouted into solidarity with others who’ve been systematically excluded from the comfort and power enjoyed by the Asher Jaffees of the world—the people on whom the wealth of such men depends. But what Brooke actually has in mind is both more individualistic and more self-sabotaging. Her plan comes to a head during a party at Asher’s Connecticut estate, when her increasingly erratic behavior leads to a desperate final confrontation with her boss.

Cornered about her unsanctioned expenses on the company card, Brooke finally asks Asher outright to buy her the 29th Street apartment. When he demurs—“It must be difficult to hand out my money. But we’re addressing need. Not want”—she makes a veiled threat to accuse him of sexual harassment, then immediately pivots, offering to bear him an heir in exchange for this gift. It’s a dagger for Asher, whose beloved only daughter, an analyst at Cantor Fitzgerald, died on 9/11. Finally cast out of his good graces and his home, Brooke leaves the party barefoot, going nowhere in particular. Only her self-deception remains: “She was free.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Are we to take Brooke’s breakdown as an indictment of Asher and all he represents: wealth hoarded and then bestowed in exchange for influence, the arbitrary advantages granted to those born white and male? It’s difficult to say; Alam muddies the water by alluding to his protagonist’s mental fragility as early as the novel’s opening. Its very first line is a self-conscious rewrite of Sylvia Plath’s in The Bell Jar: “It was a strange, sultry summer, the summer of the Subway Pricker….” Entitlement makes clear even throughout its early sections that, like Esther Greenwood, Brooke is a woman on the verge of unraveling. She comes across less like a hyper-competent idealist undone by the excesses and hypocrisy of the philanthropic-industrial complex than a woman whose ruthlessness is compensating for a hollow core; perhaps any line of work would have pushed her over the edge. At many points in Entitlement, Alam seems to be winding up to a critique that never fully materializes, allowing ambiguity to soften the sharp edges of social criticism.

Entitlement also equivocates over aspects of its own plot. The novel sometimes refuses to disclose whether Brooke has truly acted out in a bizarre fashion or instead has only imagined doing so: “All this, no, maybe, but, perhaps, all these possibilities, all these selves,” Alam writes after one such incident, when Brooke either does or does not push a woman after a confrontation in a coffee shop. Even her name becomes part of the gag, explicitly acknowledged as an expression of uncertainty: “Brooke Orr” being indistinguishable from “Brooke, or?”

The novel is shot through with this kind of ambiguity, which comes to the surface explicitly as a theory of art. At one point, Brooke and Asher are at dinner, discussing a Helen Frankenthaler painting she has recently convinced him to buy for his wife. He remains uncertain about the piece, convinced that he might still be missing something he’s supposed to see in its brushstrokes. Brooke, however, is quick to disabuse him of the idea. “That’s what art does,” she tells him. “It reminds you that you feel, or asks what it is you feel. The answer doesn’t even matter. It’s the question.”

We get the point: All literature needs to do is pose a set of questions, and perhaps it’s even a form of philistinism to go trawling for particular answers. But upon finishing the novel, it’s hard not to wonder the opposite: If the answers don’t matter, then are the questions really useful at all?

More from The Nation

“The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy “The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy

The new show from the creators of The Office reminds us that their comedic style does now work in every “workplace in the world.”

The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…” The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…”

In his celebrated mea culpa, the German pastor Martin Niemöller blamed his failure to speak out against the Nazis on indifference. Was that the whole reason?

John Updike, Letter Writer John Updike, Letter Writer

A brilliant prose stylist, confident, amiable, and wonderfully lucid when talking about other people’s problems, Updike rarely confessed or confronted his own.

The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme” The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme”

Josh Safdie’s first solo effort, an antic sports movie, revels in a darker side of the American dream.

TikTok’s Incomplete Story TikTok’s Incomplete Story

The company has transformed the very nature of social media, and in the process it has mutated as well—from tech unicorn to geopolitical chesspiece.