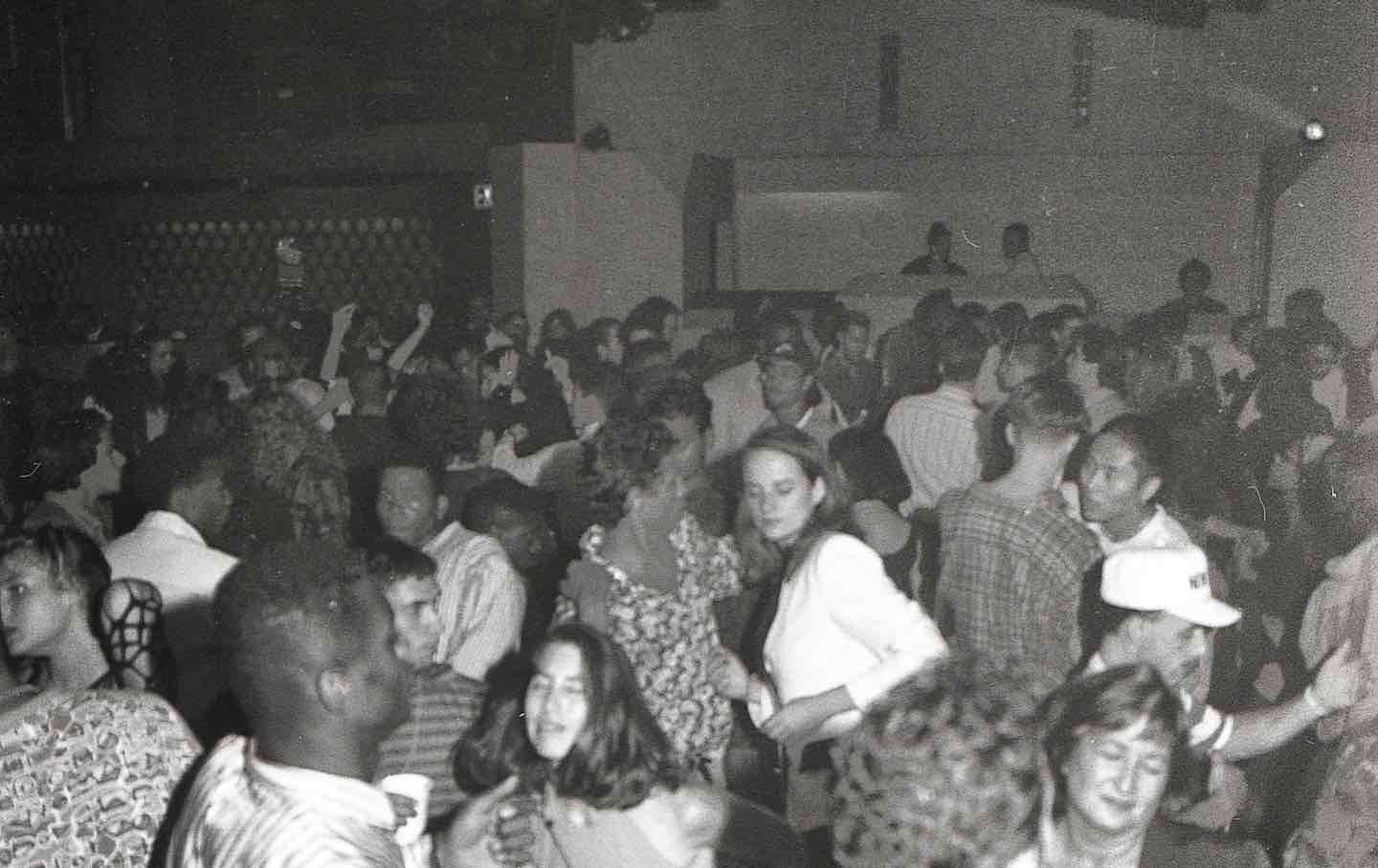

A party at Danceteria in New York City, 1990. (Photo by Bill Tompkins / Getty Images)

Sasha Frere-Jones is an institution of music criticism in an era when music critics are no longer institutions. Roughly over the course of the 1990s, Frere-Jones made a transformation that can usually be made only in theory, if not complete fantasy: He built a practice as a gigging musician and contributor to fanzines into a full-time career as a commentator for legacy media. From 2004 to 2015, he served as the pop music critic for The New Yorker, articulating the magazine’s taste in music more definitively than any critic to hold the role since Ellen Willis. Now, in his new memoir Earlier, he applies the theories he developed writing about chart-topping pop, the indie underground, and the contemporary avant-garde to a critic’s most elusive subject: his own life.

Frere-Jones’s critical preoccupations are many, including race, technology, and money, but chief among them is a materialist’s attention to the possible ways that sound can fill and segment time. In a 2000 LA Weekly piece about downtempo music, he explained: “A beat, more or less related to hip-hop, is set up, sounds and melodic fragments float above it, and things go on for a while, sometimes a really long time.” For Slate in 2003, he described Radiohead’s late style as “moving closer and closer to long sustained sounds and subdued timekeeping.” Writing about the composer Éliane Radigue for Artforum, he concluded that her nonlinear compositions “cannot be excerpted or sliced into representative swatches or versified.” Earlier is Frere-Jones’s masterwork because it extends this approach to listening—one rooted in observation, prioritizing structure and form over interpretation, and interested in movement, disruption, and change as aesthetic gestures—to an entire lifespan, an exercise that culminates in the book’s defining aphorism: “Time is what the heartbeat divides.”

Initially, the nonlinear structure of Earlier seems to lift from the dozens of DJs and hip-hop producers whom Frere-Jones name-checks in its pages. Episodes from his life are clipped, recalled from the past, juxtaposed alongside others they don’t naturally complement until they’re forced into conversation with each other. As Frere-Jones’s ruminations accrete, a continuity of vision and project emerges. The episodes capture the course of a life at moments when the terrain shifts underfoot and one has to adapt to keep one’s bearings and continue on. Page by page, sentence by sentence, this method and structure produce scintillating reading. In the long run, when treating central themes like addiction and grief, their effect is more elliptical, even riddling.

Anxiety emerges as a destructive, or at least confounding, force in Earlier, beginning with the financial insecurity of Frere-Jones’s family life in the Fort Greene neighborhood of Brooklyn. “It has become tangibly and manifestly clear that things are going to fall apart at any minute because they quite obviously do,” Frere-Jones writes in one chapter. “You run out of tuition money, you run out of rent, your best friend’s parents cop a double shotgun suicide, your father dies. Bad things can happen and likely will.” Frere-Jones didn’t lose his own father until he became a father himself, but their relationship impacted his development in similarly destabilizing ways.

When he was still prepubescent, Frere-Jones discovered that his father had been living a secret life, which at one point included a sexual relationship with the man Frere-Jones grew up knowing as Uncle John. “It is 1977 and I am ten,” he recalls. “So these data are just opaque the first time around.” Later on, he confides: “My father loves the people around him and is also unable to see his needs as anything other than incredibly urgent missions the people around him must complete.” These revelations live on and reverberate in Frere-Jones’s psyche. In college, he named his anxiety “the Golf Ball, because it seems like a thing that could only be hidden with difficulty. It is going to be either visible or felt, never eliminated. Wherever you stash it, you will sense it.”

Music is what ultimately taught Frere-Jones to observe and reconcile the sense and shape of all this instability and flux. Remembering playing in his first band as a teenager, he proclaims: “I realize I need that skill, the ability to generate a map, if not a traditional score; an ordinal series of cues.” Around the same time, Frere-Jones began taking trips to Manhattan to buy records (Madonna, Kid Creole and the Coconuts). Listening to them in his room, he thinks: “This is liberation, freedom, and goodness. This will lead somewhere. I will produce these records, play bass on them, something.” For Frere-Jones, as for many lifelong fans and self-styled connoisseurs, music was the first thing in life to solve a problem.

His commitment to listening for and scoring life’s natural rhythms led Frere-Jones to a copywriting job at Columbia Records’ mail-order music club Columbia House; some inconsistent but appreciable success with his band, Ui; and, finally, a writing career. Contributions to friends’ zines turned into one-off reviews for newspapers like the New York Post and then a staff job at The New Yorker. The amorphous, indeterminate nature of Frere-Jones’s experience would eventually be translated into the writing style it uniquely informs. As a child of New York City’s 1970s and ’80s, an erstwhile punk and denizen of downtown, Frere-Jones’s affect as a critic was mediated through slang and urban life: Popular music itself is a kind of advanced, technologized slang, which makes it a perfect focus for an addled psyche.

This ear for vernacular speech and behavior also makes Frere-Jones acutely aware that the culture of the city he lives in is as transient and tenuous as his own identity. In the New York of his youth, “there is breakdancing in the streets…and graffiti…. There are the clubs, most importantly.” His favorite dance records “are played at Danceteria in all their glorious sonic heft and at considerable volume.” But years later, after “the incursions of drugs into the clubs, the neutron bomb of AIDS, and the advent of Giuliani’s fist politics and the cabaret laws…we lose the consensus that dancing is a default social activity and the idea that hip-hop is primarily dance music.” This is one of several lapsarian moments in Earlier, the most significant of which is Frere-Jones’s reckoning with alcoholism.

In popular media, stories of addiction and recovery invert the conventional narrative arc: Instead of a series of rising actions, the addict’s conflict is a slow descent, until the addict hits bottom and climbs in recovery back to zero. In Earlier, this is not what addiction looks like, because this is not what life looks like: Addiction is not a dead end, just unfamiliar territory. Besides eagerly hitting the open bar a couple of times at events he covers for work, Frere-Jones never exhibits the spectacular behavior that readers of popular memoir might expect from an addict in thrall. Instead, addiction becomes real in the presumed aftermath of these episodes, in the doctors’ offices and mental health clinics in which Frere-Jones consciously assumes and performs the work of recovery.

In one of the longest sections of the book, “A Summer of Listening (2019),” Frere-Jones catalogs the music he heard over the weeks he spent in treatment at his psych ward and then in rehab. What dominated was radio pop and R&B like “I’m Blessed” by Charlie Wilson, “Sucker” by the Jonas Brothers, “Old Town Road” by Lil Nas X. In reaction, Frere-Jones craved “music that is soggy-in-your-clothes heavy like Marvin and Sabbath.” He had a recurring dream about Richard Ashcroft of the Verve. When he left, the first thing he wanted to hear was King Crimson. But Frere-Jones is no enemy of pop radio: His dissatisfaction was his in-the-moment indication that he was undergoing psychological repair. Addiction is not a corruption of one’s character but rather a disturbance of one’s relationship to the outside world, and music is the constant against which to measure that relationship.

Just as addiction disturbs this relationship, so does love. The first time Frere-Jones spent the night with Deborah, who would become the mother of his children (and to whom the book is dedicated), she played him a David Byrne song. Although he was skeptical of Byrne by that point, Frere-Jones writes, “I see her big liquid eyes and easy smile, her sweet little buck teeth, and I realize that I want to love things the way she loves them, without additional anxiety about where it might fit into the world, thinking only of where it fits inside her.” Deborah died in 2021, and the book reflects the work of processing her loss—but like the depths of Frere-Jones’s addiction, the grief itself is not broadcast on its pages. Instead, grief is measured by the accumulation of moments spent loving the person who, in the world beyond the book, is no longer here.

Earlier resists linear advancement and dwells on metaphysical quandaries, but it still observes and honors certain traditional mores: Age and experience are sources of wisdom, and family is a source of strength. Growing up in the ’70s and ’80s and participating in the DIY publishing and indie rock subcultures of the ’90s make Frere-Jones a veteran of the same cultural epoch that produced the New Sincerity, a movement founded on the hope that the cataclysm of postmodernism could be overcome through individual demonstrations of compassion and caring attention. Frere-Jones seems to be well aware that on the broader social scale, this has not panned out. As a program for weathering personal cataclysm, it may be more instructive.

Stephen Piccarellais a freelance writer whose work has appeared in n+1, The Believer, and The New Inquiry.