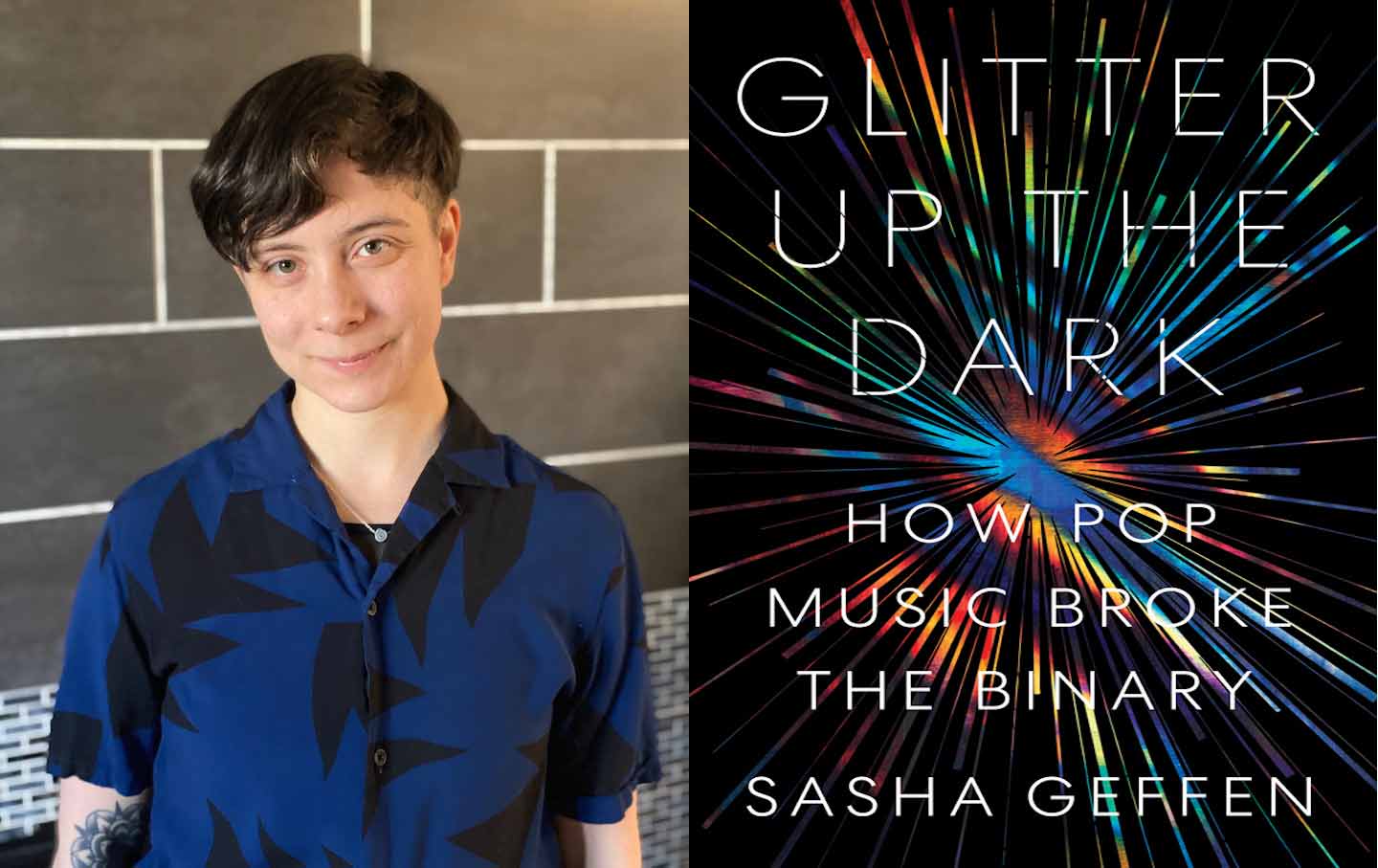

Sasha Geffen’s first encounter with a trans person was listening to Wendy Carlos, the A Clockwork Orange composer who helped develop the synthesizer as a musical instrument. The first time Geffen (who uses “they/them” pronouns) remembers hearing the word “androgyny” was in reference to Annie Lennox, and they were, like the other gay kids in high school, a big fan of the punk band Against Me. Transition (or in Geffen’s words, “figuring shit out”) became possible through music. Glitter Up the Dark is not just a chronicle of the transgressive possibilities of pop music but also a history of Geffen’s listening and a demand that we regard pop culture in explicitly political terms.

As they trace how music acts as a vessel for gender transgression, Geffen connects Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, the early blues singer who they say “set the stage for pop music’s tendency to incubate androgyny, queerness, and other taboos in plain view of powers that would seek to snuff them out” to a long history of musical expression—from Kurt Cobain and Courtney Love to Brooklyn rapper Young M.A. and Björk collaborator serpentwithfeet. As in much queer writing, origin is precious material, and the past informs Geffen’s reading of contemporary mainstream cultural production as well as today’s conversation surrounding gender identity. (“The history of American music is the history of black music,” they write, “and since the gender binary is inextricably tied to whiteness, pop music’s story necessarily begins slightly outside its parameters.”)

The book is also a collage of voices that quietly unsettle the status quo, nimbly linking artists one would expect to see in this sort of anthology (Prince, David Bowie, Missy Elliot, Grace Jones) and others who are more surprising (the Beatles, DJ Kool Herc, Klaus Nomi). If Geffen’s thesis is that “music shelters gender rebellion from those who seek to abolish it,” then the book operates in a similar way, circulating clues about Geffen’s realizations about gender alongside each artist they profile.

I spoke with Geffen by phone, sometime after they’d completed Glitter Up the Dark. Our conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

—Taliah Mancini

Taliah Mancini: Gender is often thought about in terms of performance and reception, which is in turn thought of in visual and bodily forms. Why is voice such a critical site for gender nonconformity, fluidity, and refusal?

Sasha Geffen: The idea that gender is performative—that it occurs in the interaction between the eye of the beholder and the outside of the performer’s body—is pretty well explored, but it didn’t encompass my full understanding of my own gender or my interactions with other trans people. That gender is performative doesn’t mean that it’s superficial, and so voice became a way of exploring how gender works inside the body. It also squared with my history and experience as a listener. When I was maybe 11, airplanes had airplane “radio,” which was actually just two hours of preprogrammed music, and one of the songs I heard on there was Savage Garden’s “Truly, Madly, Deeply.” It was a song I’d heard before in mini form on the Internet. I originally thought [vocalist Darren Hayes] was a woman but discovered that he was very androgynous, not only in voice but also in presentation. I became obsessed. I brought a picture of this dude to the person who cut my hair when I was 12 years old. Looking back, it’s very obvious that this was the beginning of my whole gender situation—this idea that information about the body and its relationality can be inferred from voice. I’ve always been drawn to vocal music for the ambiguity, but more recently, I’ve been doing research into lip-synching as a drag practice. How the female voice can animate feminine men is a big clue as to how voice can work in terms of gender and affinity.

TM: Is the trans voice describable?

SG: A lot of contemporary artists I write about in the book, like Arca and Sophie and Fever Ray, were not out when I and many other trans fans started actively listening to them. I’ve had coworkers ask me “What do you hear in this?” and honestly the best answer I can come up with is just “trans.” It resonates in my body in a way it won’t in yours because you don’t have this weird experience of being ill-fitting in the dominant schema.

Right now I’m thinking a lot about synthesizers as a kind of artificial voicing that squares with synthetic hormones and other performances that are seen as false by certain subsets of society. This goes back to Wendy Carlos, the first person to ever use Vocoder. I eagerly want to interpret Carlos as a specifically trans artist, but she has never wanted to talk about her transness. There’s a generational shift here. Doctors also didn’t want trans patients to carry their transition as a topic of conversation into their present life. Still, I think it’s important that one of the people most responsible for how synth sounds in pop culture is a trans woman. Someone who worked to embody the synthesizer as it is now—who had the idea to do touch-sensitive keyboards and who made the interface a lot more accessible—was also someone who was working on her own embodiment.

My ears perk up for this processed voice, this voice that blurs the line between “natural” and synthetic—which relates to the trans body, this body that blurs what’s endogenous and what’s exogenous. That ambiguity is productive for a lot of trans people. Or it isn’t, and we just want to get on with our lives, but I think a lot of trans artistic practice focuses on that confusion. In music, it might just come in certain inflections—technological breaks with Auto-Tune and Vocoder or natural ones where the voice kind of yelps in the throat. “Breakage” is a good word to describe what I’m hearing.

TM: You survey a number of artists who operate as foils for cis fans to act and desire in ways that are scripted as deviant. How does fandom play into all of this?

SG: In the diaries of [writer and gay trans activist] Lou Sullivan that got published last year, Lou, living as a teenage girl, talks about his own Beatlemania and wanting to get a Beatle haircut and wear Beatle boots. Fandom is a kind of safe avenue of expression for people perceived as teen girls, one that trans femininity doesn’t necessarily have. The Backstreet Boys and ’NSync were definitely styled to be palatable to teen girls, to look younger than they really were and more feminine than they might have otherwise been. Maria Sherman, who just wrote a book about boy bands, recently shared a Simpsons screenshot of a teen magazine with the title Non-Threatening Boys. Boy bands are not quite in the precipice state where they have sexuality, and they’re also not confident in it in the way an adult male is seen to be. Forced naivete allows boy bands to emulate femininity in a way that is not taken as a danger to the heteronormative order.

TM: The book reads like a history of technology just as much as one of gender or music. Your documenting the technological shifts that have shaped pop culture is incredible. At the same time, I can’t help but think about the ways that tech threatens queer life.

SG: Technology is a concern for everyone who is looking for a way out of hell right now, which is certainly not just trans people. Political solidarity has to be in person to some degree, especially now that everything is algorithmically sorted by the heavy, impersonal hand of the machine. In terms of music, we’re in a weird moment where platforms like Spotify and YouTube and SoundCloud are life-giving in that they allow for cheaper or free access to music, but this is at the expense of the artist, who is working at a severe deficit, only earning enough to live through touring or licensing—or more direct deals with capital. You can’t sell music itself anymore, unless it’s to an advertising company.

We just have to keep burrowing into the available infrastructure and finding each other in an attempt to elude the gaze of the technocrat overlords. It helps to be confusing to the powers that be but not to each other. I’m interested in using technology as a tool and a portal but also paying attention to the body and what can’t be accessed by the Internet, connecting on levels that go beyond what surveillance can readily examine, and trying to garble the channels that swoop up all our data and use it to advertise to us. How can we make base connections online and then transfer that into building offline solidarity with each other? A lot of people with various disabilities can’t just get out, but it’s a trajectory to follow, optimistically.

TM: You write that the history of pop music is inseparable from the history of black survival. How important is white theft for pop music as we know it?

SG: In the first half of the 20th century, around the time that music became a business, white record executives realized that, in an America coded around white propriety and white desire, white people wanted to buy things that sounded dangerous to them. Like now, there was a period of time when black artists were selling very well but—while there were black record labels selling black music—the majority of capital was in the hands of white people. These record execs cut a lot of deals with black artists, like Little Richard, but did not give them support.

From that foundation, we get the phenomenon of Elvis. When you hear Elvis sing, you hear Big Mama Thornton and white country singers and white proto-rock singers. Even though we now think of Elvis as infallibly masculine—he’s become almost like a cartoon—at the time he was perceived as an androgynous presence, dancing in a way that was only seen in burlesque clubs at the time. Jazz and early rock and roll were viewed as dangerous because their sexual nature was part of a racist history of seeing black men and women as having an outer sexuality that threatened white propriety. Record executives tapped into that and made Elvis what he is, selling him as this conglomerate of various influences. Obviously, he sold much better than anyone he was parroting—and he was literally parroting, singing the same songs black artists sang and singing with the same vocal inflections. The same happens with the Beatles, who covered No. 1 hits from black girl groups, but their versions are now heralded as the authoritative ones.

[In pop music] you see this papering over of history and this reattributing of creativity and creative spark to the people that could sell better in white America. It’s not that different today, with the phenomenon of Iggy Azalea—who presents and speaks like this white girl from Australia but is trying to copy the cadence of black women rappers from Atlanta. There are a lot of black pop superstars, but there is also a lot of attention and money directed to white people parroting black styles.

TM: The book is a catalog of artists, but it also feels personal in a way that traditional memoirs do. How much was it shaped by your ear?

SG: I don’t write in the first person as much, but at the end of the day, my book follows the rhythms of memoir because it is ultimately an attempt to figure myself out. You can’t get out of the self. There is no objective stance. Every listener has their own little prism through which they hear this stuff, and I hope that lots and lots of different people write about theirs so that we can hear from as many listeners as possible about how they construct identity, how they find their own voice by hearing the voices of others.

TM: I want to ask about the coda, in which you write about transition as the fulfillment of one’s gender. Who has a stake in gender and music, and who are you writing to when you compile these histories?

SG: I was thinking about what I would want to read if I were 15 and operating from a place of extreme scarcity of information—not knowing what I am or why I am the way I am and burying myself in music to try to figure it out. I wanted to write the kind of book that would have sped things up for me if I had read it when I was a teenager—a text that was like, “Hey, the reason you’re obsessed with music and this kind of music in particular is probably ’cause you have some trans shit going on.” All people can benefit from the practice of attuning to one’s own body, though.

There’s a concerted effort to disavow the knowledge of the body and place that authority in the hands of corporations. This capitalist project is part of why there’s been such a violent reaction against the trans rights movement. The idea that an app knows more about how well you slept than you do is really indicative of where we are right now, where technology is regarded as the all-knowing, watchful eye of both the social block and the individual body. A lot of people are doing work to disempower the technological superstructure, and a lot of that work is happening in music and dance spaces, where you have to listen to what your body is doing and what other bodies are doing in a very visceral way. That is my hope, to make some small strike against the capitalist project of disembodiment and some small gesture toward a more holistic way of listening to each other and to ourselves.

Tal MilovinaTal Milovina was an editorial intern at The Nation.