Why Americans Are Obsessed With Poor Posture

A recent history of the 20th-century movement to fix slouching questions the moral and political dimensions of addressing bad backs over wider public health concerns.

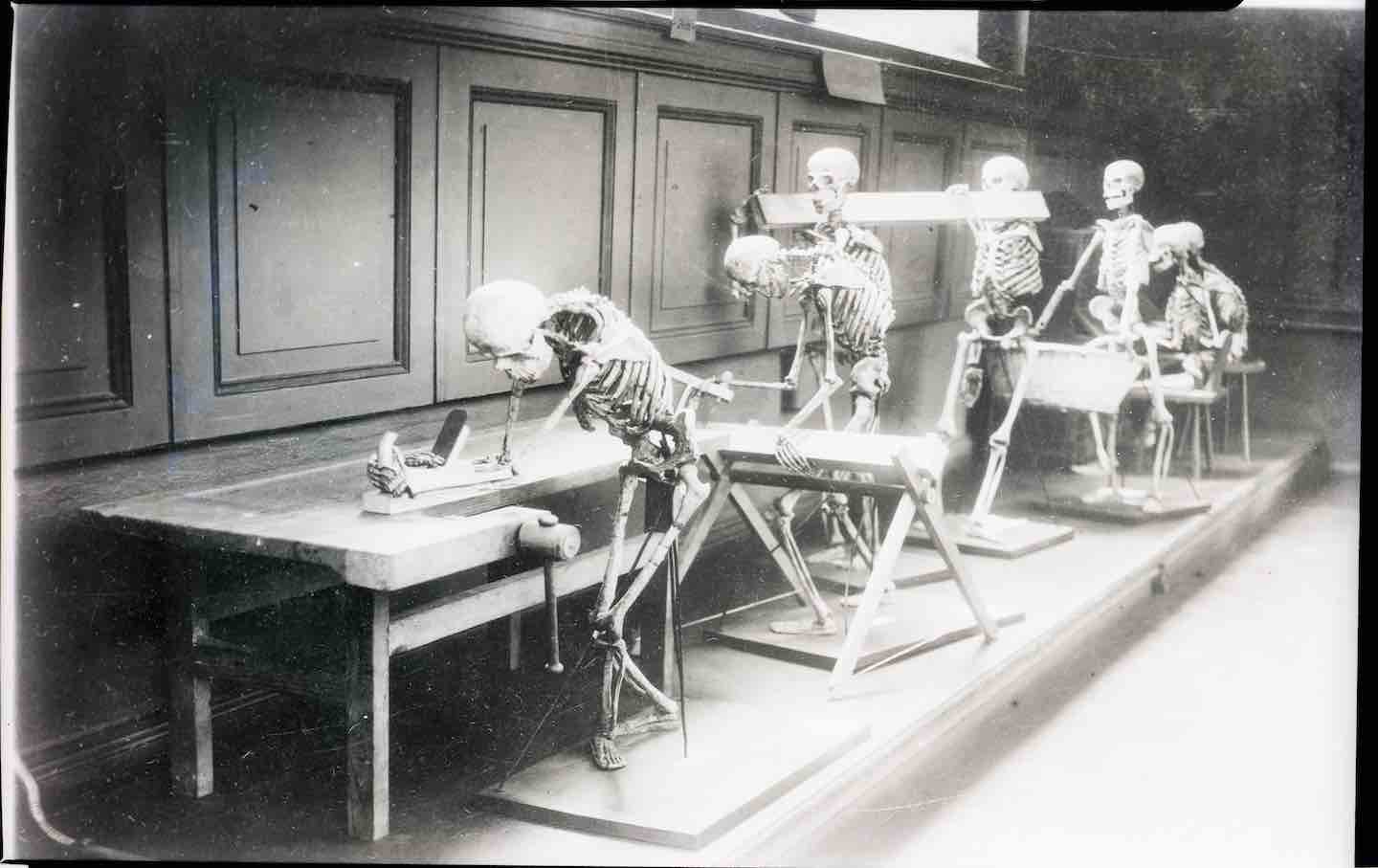

Skeletons used in a museum in Amsterdam. They are posed in various positions for working; sawing wood, doing housework, carrying planks, office work, etc.

(Bettmann / Getty Images)

“Imagine a string pulling the top of your head towards the ceiling,” my barre instructor announced to the room. My body was shaking. I looked around the packed studio and saw a sea of predominantly white bodies in matching workout sets, all striving for an ideal elongated frame. Our instructor invited us to smile through the pain, as if baring one’s teeth could evaporate discomfort. After my first class, I received a handwritten postcard from the studio. An anonymous staff member, writing in pink gel pen, congratulated me on “100% embracing the shake!” I immediately threw out the card. But the next day, I signed up for another class.

Books in review

Slouch: Posture Panic in Modern America

Buy this bookAs an internal medicine resident, my job largely consists of sitting in a chair. I run around the hospital and see patients, but that’s only a small fraction of my day. I am usually hunched over a desktop in a windowless workroom. I don’t need a mirror to know my posture is horrific. The exhaustion of residency has made me feel estranged from my own body. Barre—with its focus on posture and alignment—brought an awareness back to my physical self that the years of school and residency had taken from me. I took the skills I honed in barre to the hospital, smugly tightening my core as I looked at my fellow residents slouched over their computers. I then noticed that my elongated spine brought benefits that transcended the physical: Were my male attendings taking me more seriously? Did my patients regard me as displaying more authority? Could good posture make me feel like a more competent doctor?

We’ve all been told to stand up straighter. But the scold isn’t necessarily connected to our health.

The back’s central place in the psychodrama of our personal health is so commonplace that we don’t really question its origins. Beth Linker, a historian of science and former physical therapist, uncovers just how recent our obsession with posture is in Slouch: Posture Panic in Modern America. What she finds is a moral panic, one that began in England at the turn of the 20th century with the rise of evolutionary science and its impact on human health. Posture migrated from a debate over anatomical development to a concern that popped up everywhere throughout the 20th century, a symptom tied to a whole host of anxieties around race, class, and industrialization.

How did concerns about posture become so ubiquitous? Instagram ads featuring posture-enhancing technologies like standing desks, ergonomic chairs, smartphone apps, and the FDA-registered posture-correcting bra that Taylor Swift wore while training for her Eras Tour consume my feed. And why have we attached so much meaning to posture? A child sitting upright at the family dinner table continues to symbolize respect, and colloquialisms like “upright citizen” signal virtue. Some people may purchase the viral posture bra because they feel a taller stance makes them more attractive or commanding. Others feel the bra or standing desk actually improves nagging back or neck pain. There is a blurriness here: How much of this concern with posture is a moral panic or pseudoscience? And to what extent might poor posture and its contribution to pain be a legitimate issue?

Linker’s history opens in the late 19th century, with a debate concerning the first step in human evolution. The question at hand: Did the human brain develop before humans stood upright or after? Charles Darwin was a member of the “posture-first” camp, using the principles of natural selection to argue that humans’ ability to stand upright preceded brain development. Darwin’s stance was controversial because he claimed that a small physical difference—rather than an intellectual one—was what initially separated humans from apes. While Darwin wasn’t a medical doctor, his ideas circulated among British and American paleoanthropologists who also happened to be physicians. These physician-paleoanthropologists had a stake in applying evolutionary science to clinical practice and became fixated on posture as a tangible “indicator of evolutionary fitness,” Linker writes.

Ever since Darwin identified posture as an important evolutionary trait, anxieties about the social order were projected onto it. Beginning in the post-Victorian era, the emergent professional middle class regarded the aristocratic leisure class with disdain, dubbing their slovenly stance the “debutante slouch.” The working class came under similar scrutiny in America: Factory workers, often recruited from the ranks of recent immigrants, hunched over their machines, ruining their backs in the process.

Regardless of class, the demands of an industrialized economy undeniably affected human posture. The creation of Henry Ford’s assembly line—informed by the principles of “Taylorism”—made work increasingly repetitive and stationary, contributing to the rise of medical conditions like flat feet, scoliosis, and back pain. Poor posture was everywhere, and it needed to be corrected. Or at least that’s what the emergent “posture scientists” thought. The proponents of posture science were far more concerned about correcting bad backs than addressing unsafe working conditions, a more serious driver of poor health outcomes.

Before posture could become a true issue, even a medical panic, it needed to become a legitimate science to have staying power. Linker deftly tracks the medicalization of posture, starting with the American Posture League (APL), an organization founded in 1914 by Jessie Bancroft, a physical educator from the Midwest known for her commitment to the “new physical education movement,” where an emphasis on the “psychosocial” aspects of exercise figured prominently. Prior to founding the APL, Bancroft was the assistant director of physical education for New York City’s vast public school system in 1904. Bancroft took advantage of this position of power to use New York’s most vulnerable children as a canvas for correcting what she deemed to be an epidemic. The APL—whose ranks included orthopedic surgeons and other medical doctors in addition to physical educators—would be formed a decade later, with the goal of spreading awareness about the negative health effects of poor posture on a national scale.

Bancroft was not interested in New York City’s privileged children. Rather, she wanted to study immigrant children who lived in “the crowded tenement section, where undeveloped standards of living, ethical sense, personal ambition and ideals, and an embittered attitude toward all government, formed the basic problems for our country.” Posture could be used not only to correct future health problems but to further American nationalism, policing the bodies of the immigrant populace under the guise of science. This nationalistic drive would come to define the mission of the APL, whose members viewed themselves, Linker writes, as “vital to the Americanization process, molding the bodies of would-be citizens.”

As phys-ed director, Bancroft found that over half of New York City’s public school children suffered from poor posture. She made this discovery using her rudimentary vertical-line test, which involved lining students up in profile next to a metal pole that noted postural defects. This statistic led the APL to develop more refined measurements that could be implemented across the country. Enter the schematograph, an instrument that used a reflecting camera furnished with tracing paper to allow its operator to outline a mostly naked figure’s posture. The schematograph took off: Every female freshman who entered Stanford University in the early 1900s received a schematogram. Dozens of colleges and universities across the country soon adopted the technology. By the 1950s, more than 30 years after the founding of the APL, Smith College students still needed at least a B- in posture to receive their diploma.

Though Linker doesn’t specifically discuss posture science in relation to the eugenics movement, which emerged in the same years, she shows us the unexpected ways that scientific racism played out in assessments of posture. The APL’s “Good Posture Pin”—awarded to students with Grade-A posture—featured a commanding image of a Lenape man in profile. Posture scientists fetishized Indigenous communities because they were “untouched” by the corrupting forces of society that made Americans prone to slouching. Similarly, the APL idealized head-carrying customs among African and Indigenous communities. But Bancroft and others were quick to remind students that what objects they decided to balance on their heads mattered: Books signified an educated, upper-middle-class lifestyle; baskets or basins were too practical and working-class.

The posture panic quickly moved out of America’s schools and into branches of the federal government and the military, where posture inspection became part of physical exams for immigrants, the US Navy, and nationwide studies of children’s health through the US Public Health Service and the US Children’s Bureau. After World War I, increasingly conservative approaches to public health—which historians have called “the new public health movement”—were gaining popularity. Public health historian Nancy Tomes argues that proponents of this movement wanted to “remove medicine from partisan politics,” focusing instead on individual health and disease prevention. Posture science and the APL exemplified the new public health movement, allowing the government to neglect the structural determinants of health that impacted the urban poor, such as poverty, racism, and dangerous working conditions.

This is made glaringly evident in a 1920 National Child Welfare Association poster that warned of the link between poor posture and tuberculosis. The poster depicts the biblical story of David and Goliath, with David representing good posture and Goliath tuberculosis. It reads, “Poor posture encourages tuberculosis. Erect carriage combats it.” The pseudoscientific link between posture and tuberculosis distracted the public from the true drivers of the tuberculosis epidemic: overcrowding, poverty, and homelessness.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Posture also figured prominently in the push for racial uplift among the Black elite in early 20th-century America. Dr. Algernon Jackson, a Black physician who worked with Booker T. Washington to establish the National Negro Health Movement, once said that young African Americans “too often slump along stoop-shouldered and walk with a careless, lazy sort of dragging gait.” The parallels to contemporary respectability politics are obvious: New York City Mayor Eric Adams’s “Stop the sag! Raise your pants! Raise your image!” billboards come to mind.

Black women were doubly marginalized due to their gender and race, with proper posture and beauty training functioning as a “behavioral entrance fee…to the right of full citizenship.” As one historian notes, posture assessments in Black finishing schools “veered towards performing whiteface,” teaching white beauty standards to ensure that working- and middle- class Black American women could achieve economic security. Historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) also hosted statewide posture pageants judged by members of the APL. The winner received the infamous posture pin with the Lenape man on it.

In her introduction, Linker states that she is not interested in adjudicating “the realness of the posture epidemic or the degree to which poor posture was and is debilitating.” As a cultural historian, her decision not to explore the legitimacy of posture science is understandable—she studies how knowledge travels, not the science itself. But this choice leaves the reader with an incomplete portrayal of how poor posture became a health epidemic. Is the concern with posture a moralizing junk science with no basis in fact? Or is it something more nuanced?

According to Linker, the commercialization of posture in the 1920s and ’30s catapulted posture science into the mainstream. Sensing a hole in the market, companies advertised solutions to the poor-posture epidemic in the form of ergonomic chairs, orthopedic shoes, belts, and girdles. Our appetite for posture-promoting devices and fitness programs persists today. Approximately $1.25 billion is spent annually worldwide on these devices and on exercise classes from barre to Pilates to the Alexander technique, private lessons where an instructor observes a student walk and sit while making manual adjustments to aid in posture improvement and muscle relaxation.

But the story is more complex than a capitalist push to promote a health fad. After the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City, textile workers’ unions—made up of predominantly Jewish immigrant women—advocated for safer working conditions and improved seating, as most factories only provided benches or stools for their workers. Linker includes an eye-opening photo by the Progressive-era documentary photographer Lewis Hine that shows three child laborers sitting on wooden stools with their curved spines facing the camera. Hine used photography to raise awareness about child labor and “work scoliosis.” In the wake of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, researchers began to study chairs for industrial workers, leading to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology “work chair,” which had a bend in the bottom of the chairback to provide lumbar support. After four months of using the MIT chair, textile workers reported decreased fatigue and pain.

Yet, instead of framing ergonomic chairs as a possible advancement in workers’ rights, Linker doubles down, characterizing the posture scientists behind the MIT chair as practicing another form of manipulation, one used to “instruct and inform individual bodies without requiring such persons to be cognizant of it.” Didn’t workers advocate for these chairs? Wasn’t this a public health win for the working class? What about workers’ reports of decreased pain? Sometimes a chair with lumbar support is just simply a good thing.

Other than a few pages detailing President John F. Kennedy’s quest to cure his lower back pain, Linker does not entertain the most important potential negative health effect of slouching: back pain. Back pain is the most common complaint in any doctor’s office in the United States. Clearly, any supposed relationship between posture and communicable diseases like tuberculosis is laughable. But posture’s connection to pain seems like an area worth exploring with more subtlety. In a recent New York Times interview, Linker calls posture science “fake news.” Yet if this is the case, what do we do with the evidence or patient anecdotes that state the opposite? Back pain can be intractable and difficult to address for thousands of patients; chronic musculoskeletal pain continues to be a known driver of addiction to prescription opioids. If there was a safe and inexpensive way to alleviate this suffering—even in the form of a placebo—shouldn’t clinicians lean in?

A 23-year-old patient recently came into my primary care clinic for an annual physical. We talked about a lot of things—his job, anxieties about the future. After a pause, he gestured to his upper back. He looked at me rather urgently and said, “Dr. Adams, I’ve been having bad back pain. My neck also hurts sometimes. Do you think this has anything to do with my bad posture?” I had no idea how to answer him.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks

The late actor and director leaves behind a roster of classic films—and a much safer and juster California.

Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments

Dev Hynes moves between grief and joy in Essex Honey, his most personal album yet.

Ars Poetica with Backup from The Clark Sisters Ars Poetica with Backup from The Clark Sisters

after “Is My Living in Vain?”, 1980

Helen DeWitt and Ilya Gridneff’s Sweeping Anti-War Novel Helen DeWitt and Ilya Gridneff’s Sweeping Anti-War Novel

Your Name Here dramatizes the tensions and possibilities of political art.