Feminism Against Itself

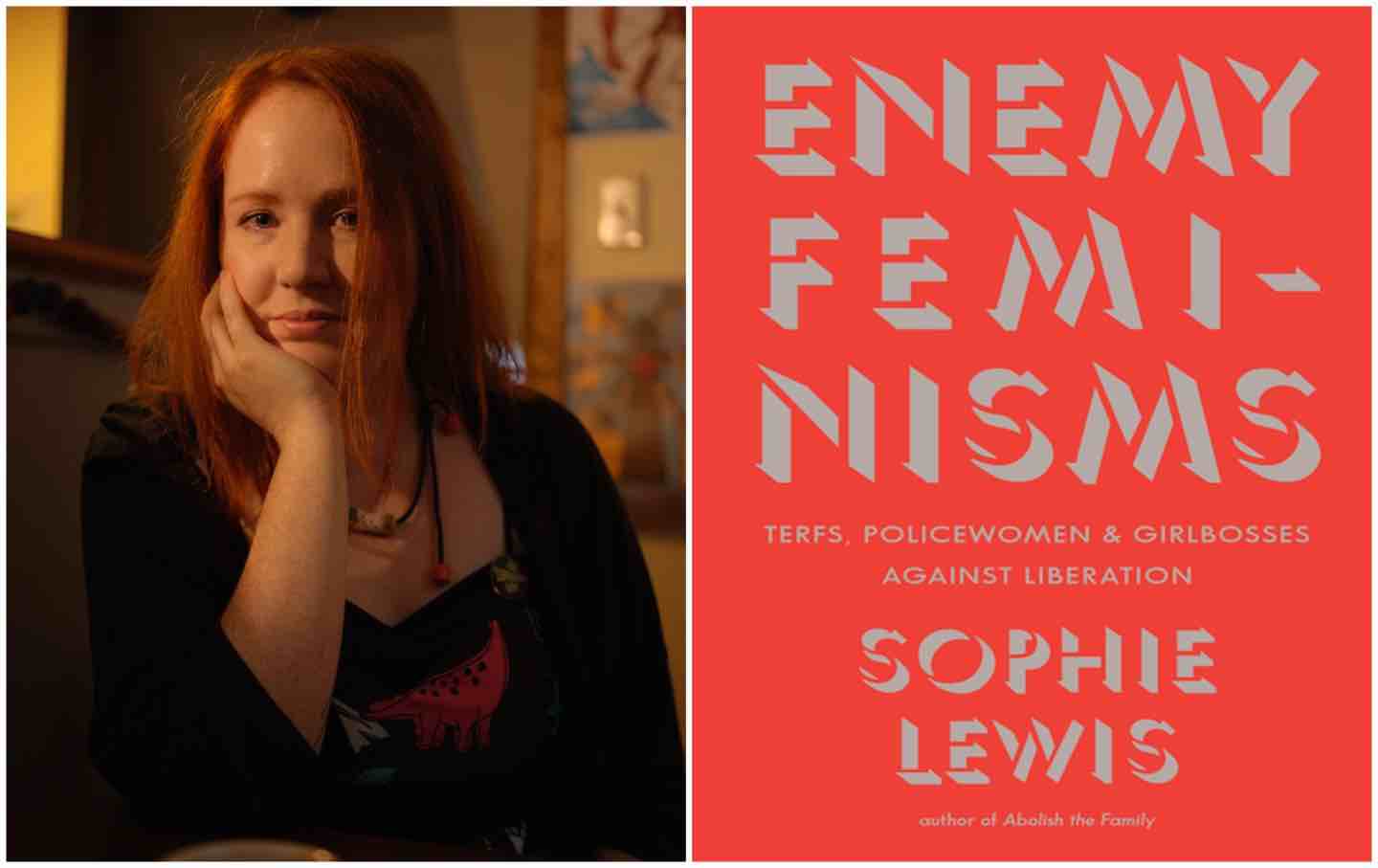

Sophie Lewis grapples with the ways the feminist movement has harbored prejudices and abetted wrongdoing in Enemy Feminisims.

Every institution is prone to rot—even great causes like feminism. It should be no controversy to affirm, Sophie Lewis writes, that often “women are horrible.” So begins the feminist critic’s new book Enemy Feminisms, in which she catalogs a “bestiary” of enemies: girlbosses, TERFs, and imperialists who claim to advance the cause of womankind while actually undermining the cause of liberation. This is the driving question of Enemy Feminisms: Is feminism always inherently good?

Books in review

Enemy Feminisms: Terfs, Policewomen, and Girlbosses Against Liberation

Buy this bookThe problem with that formulation, Lewis argues, is that feminism, as a political category, is inherently contradictory—the movement’s history “has whiteness baked into its very core” and is perfectly capable of accommodating warring camps. Lewis wants to understand the enemies swarming within our ranks because true solidarity requires more than just basic common ground: We need “comrade feminism,” she writes, the ability to link arms through shared goals without reverting to regressive ideas of imperialism, racism, or transphobia. Only then can we kill the girlboss in our minds.

By taking on the pornophobes, Blackshirts, pro-life advocates, Islamophobes, and femonationalists of yesteryear, Lewis aims to expose the gaps in our current understandings of feminism. There’s no point in breaking bread with those who crave your destruction, but a process of reconciliation is crucial for Lewis: “We can forgive a pro-life feminist and still destroy the forced-birth judiciary,” she writes. Such forgiveness does not come without its own ethical quandaries. But understanding what we are against is crucial in crystallizing what we are for.

It’s easy to feel pessimistic about organizing under such a broad banner as feminism when major brands are in the business of co-opting radical ideas for cynical cash-ins, from pussy hats to pithy graphic T-shirts. In a world with so many factions, how do we move forward? Lewis believes we must build an erotics of feminism, one that offers a more seductive vision of solidarity than the far right’s noisy stadium rallies. To create such a compelling community, we must first address what ails feminism. In her “bestiary” of enemy feminisms, Lewis dissects the dystopian paths that many women take, aligning themselves with disparate foes. But by focusing so much on those we’re against, what might we lose? How do we fight for pleasure while so gripped by the intoxicating narratives of our enemy?

Lewis first emerged as a feminist intellectual through works like Full Surrogacy Now and Abolish the Family. The provocatively titled books examined the politics of birth and pregnancy and the uniquely oppressive structure of the nuclear family. Her worldview, as evidenced by both works, is deeply rooted in the fight for pleasure and liberation. In Abolish the Family, Lewis argues that the constraints of the nuclear family act like a straitjacket on the self-determination of children, who deserve the autonomy to choose their own familial structures and networks of care. In Full Surrogacy Now, Lewis examines the debates around pregnancy and surrogacy, proposing that a greater sense of freedom is possible if we look at “gestation” not as a natural or naturalized act, but as a form of labor that has to be reimagined.

The two books, alongside a number of essays she’s penned over the years, have earned Lewis much ire on the right, including from the likes of Julie Bindel, one of England’s leading TERFs, and right-wing pundits such as Tucker Carlson. Both camps found her work’s focus on transness and abortion to be morally reprehensible, and they tarred her as merely a leftist provocateur. Yet Lewis’s writings are not solely polemical; she works to sketch a feminism that can withstand such reactionary attacks. In Enemy Feminisms, she revisits gestation and pregnancy, the primary theme of Full Surrogacy Now. In particular, she returns again to forced gestation—the idea that people should be compelled to bear pregnancies from conception to birth without the option of abortions. This is the stance of the “pro-life feminist,” one who believes we must make conditions for women and those who give birth “better” rather than codify Roe v. Wade into law.

While taking on pro-life feminism in Enemy Feminisms and in her broader work, Lewis also considers the weight of killing another being—whether a bug or a fetus. She admits that abortion is a form of violence, one that brings up crucial ethical considerations concerning agency and mortality, but she also reminds us that forced gestation is its own form of violence. The pro-life movement’s advocacy for the inviolable rights of the fetus ignores the rights of the mother. Lewis is novel in her argument for admitting that abortion can be a form of violence—and that violence should always be carefully considered, even if it is not ultimately something to avoid at all costs. “I actually agree when the proponents of forced gestating argue that giving ethical consideration to fetuses is a worthwhile endeavor in an abstract, futuristic sense,” Lewis writes. “But my anti-violence is not nonviolence, nor can any real opposition to violence be nonviolent.” One must weigh the scales.

Throughout her work, Lewis continually brings up two opposing ideas: pleasure and “cisfeminism.” One is something to fight for, the other against. Cisfeminism is obsessed with defining and protecting normative ideas of gender, safety, and the status quo more broadly. It is antithetical to the unknowable, effervescent idea of pleasure. Politics can only begin when we meet each other outside our own comfort zones. For Lewis, there is a political value in such pleasure. Such open arms welcome the possibility of a wider coalition, a feminism for the many, not just the few.

Lewis quotes fellow critic Sarah Fonseca to ask why “is everyone so obsessed with showcasing and inventorying pain when pleasure is right there, ready to be fought for?” Why is “pleasure for pleasure’s sake” considered so unfeminist? Some victims use their pain as a weapon rather than a door. These are the enemies that Lewis seeks to declaw.

It can be grim to encounter so many women who deny themselves joy, often repressing their own experiences with patriarchy in order to exert some small amount of control over their lives. By aligning themselves with racism, classism, and transphobia, some women are able to feel superior to those they oppress. Misery begets misery. Of course, these traitors are often rewarded by the men in their lives. This chain of supremacy keeps wider solidarity from developing across identities, a coalition that, if formed, could topple the hierarchy outright instead of sowing division and self-deception.

“Rather than air dirty laundry,” Lewis writes, “racist women are often more than willing to prioritize racial over sexed solidarity, and racist men, in turn, are sometimes happy to fight for racist women’s limited equalities.” This is the crux of Enemy Feminisms: the ease with which some women betray their sisters. We must learn from these offensive foremothers lest “our inability to countenance the possibility of elective affinities between feminism and fascism makes us more vulnerable to [their] seductions.”

Lewis details these negative affinities and sects with cheeky names like “The Anti-Antiracist Abolitionist,” “The Pornophobe,” “The Femonationalist,” and “The Adult Human Female.” She begins with the early feminist movement’s misplaced equation of housewifery to chattel slattery. Feminists like Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Sophia Allen were key women’s rights activists in their own eras but also defenders of propriety, empire, and whiteness. While they continue to be important historical figures, their work must be taken with a grain of salt and contextualized alongside their failures. Early feminists championed Black radicals like Sojourner Truth, only to distort their stories. The text of Truth’s iconic speech “Ain’t I a Woman?” was quickly edited by the first-wave feminist activist and abolitionist Francis Gage; the resulting text caricatured Sojourner (the speech was transcribed to give her a halting Southern dialect) and erased many of her more radical claims on gender and racial parity. Rarely did these first white feminists let Black women have any power in the movement that wasn’t symbolic.

Later in Enemy Feminisms, Lewis takes on a more contemporary thinker, the “neo-eugencist luminary” Ayaan Hirsi Ali. The radical anti-Islamic figure was Muslim by birth but fled an arranged marriage for the Netherlands. Once there, Ali served in the Dutch Labor Party before moving to the far right, writing a screenplay about the threat of Islam to the West. After the film came out, its director, Theo van Gogh, was shot and killed by a Muslim man on the streets of Amsterdam. This has served as a touchstone of Ali’s reactionary origin story, one she uses to bat away criticisms. Yet “empathy with her traumatic experience,” Lewis argues, “should not prevent any of us, however, from calling out the craveness of her weaponization of said trauma to bloodthirsty, militaristic ends.” For Lewis, Ali is a vanguard of femonationalism, a term originally minted by Sara Farris—an ideological triangulation that allows a woman-centered politics, which Ali nominally possesses, to advocate for militant and hateful policies like burqa bans under the guise of protecting the polity. Enemy feminists frequently find themselves working with forces on the right to limit certain women’s rights—whether for Muslim women, sex workers, or trans women. These alliances are more likely than we think. “Racism,” Lewis writes, “is a patriarchal form of feminism.” Such vicious collusion can be daunting.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Lewis also addresses the anti-porn feminism of Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon in order to explore how they leveraged state power to displace and marginalize sex workers and suppress lesbian smut. One lesbian writer called living through their crusade a “second McCarthy period.” These were the so-called Sex Wars. In a similar vein to the early suffragettes, Dworkin compared sex work to chattel slavery and equated porn to the trauma of the Holocaust. Such feminists often collapsed the relationship between genocide and misogyny. In such a worldview, penises are gynocidal and porn is everywhere you look. It’s all endless propaganda proliferated by the man—even porn created by women for other women is suspect. “To read MacKinnon,” Lewis writes, “you’d think strings of cum on a tongue were, transhistorically, bullets to the soul.” Instead, she admonishes us, a penis does not necessarily penetrate and “vaginas aren’t ‘sheaths.’” In other words, equating sex with violence—and consigning those in possession of certain sex organs to the role of violator—reduces the complexity of sex writ large. Lewis is skeptical of a worldview that simultaneously manages to sexualize and to chastise women for seeking pleasure. Toward the end of her book, she quotes the feminist musician Beth Elliot, whose words are a fitting response to the Sex Wars: “I personally distrust those who hate men more than they love or do anything positive for women.”

While it certainly seems important to delve into the lore of our enemies, Lewis devotes less of the book to parsing out the comrade feminism that she argues for. Like Lewis, I believe that if we do not deal with our ghosts, they will surely haunt us. But what do we miss in the eternal recurrence of Dworkin, rather than revisiting the work of Susan Stryker, Toni Cade Bambara, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, or Jill Johnston? What if we opened up the dance floor?

Developing a pleasure-based feminism is no easy task. It will require a variety of new strategies. Certainly, feasting on our enemies’ past failures isn’t the only way. Lewis hints at some possible tactics: treasuring bodily autonomy, abolishing the family, not cutting the lady cop some slack. She briefly mentions past precedents, such as STAR, Pat Parker, Alexandra Kollontai, and a variety of other socialists. These organizations and individuals worked to create autonomy outside the confines of the state, building concrete resources for the most vulnerable. Such actions were fruitful because there was no waiting; instead, everyone jumped in together to meet each other’s needs.

If we want to create a better feminism for the future, we’ll have to present more than a defensive posture. By the end of Enemy Feminisms, Lewis asserts that we may well be “in a golden age” of “transgender Marxists.” Perhaps we need to draw them out, to examine their platforms on a wider scale. The reason we must continue to examine our enemies is because the schisms from feminism’s early past are still with us, unreconciled. By exposing the monsters of our past, Lewis hopes we can craft something more durable, something worthy of the name feminism.

More from The Nation

The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…” The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…”

In his celebrated mea culpa, the German pastor Martin Niemöller blamed his failure to speak out against the Nazis on indifference. Was that the whole reason?

“The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy “The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy

The new show from the creators of The Office reminds us that their comedic style does now work in every “workplace in the world.”

John Updike, Letter Writer John Updike, Letter Writer

A brilliant prose stylist, confident, amiable, and wonderfully lucid when talking about other people’s problems, Updike rarely confessed or confronted his own.

The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme” The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme”

Josh Safdie’s first solo effort, an antic sports movie, revels in a darker side of the American dream.

TikTok’s Incomplete Story TikTok’s Incomplete Story

The company has transformed the very nature of social media, and in the process it has mutated as well—from tech unicorn to geopolitical chesspiece.