Søren Mau’s Mute Compulsion offers a unique and relatable entry into the social and economic dimensions of modern Marxist thought.

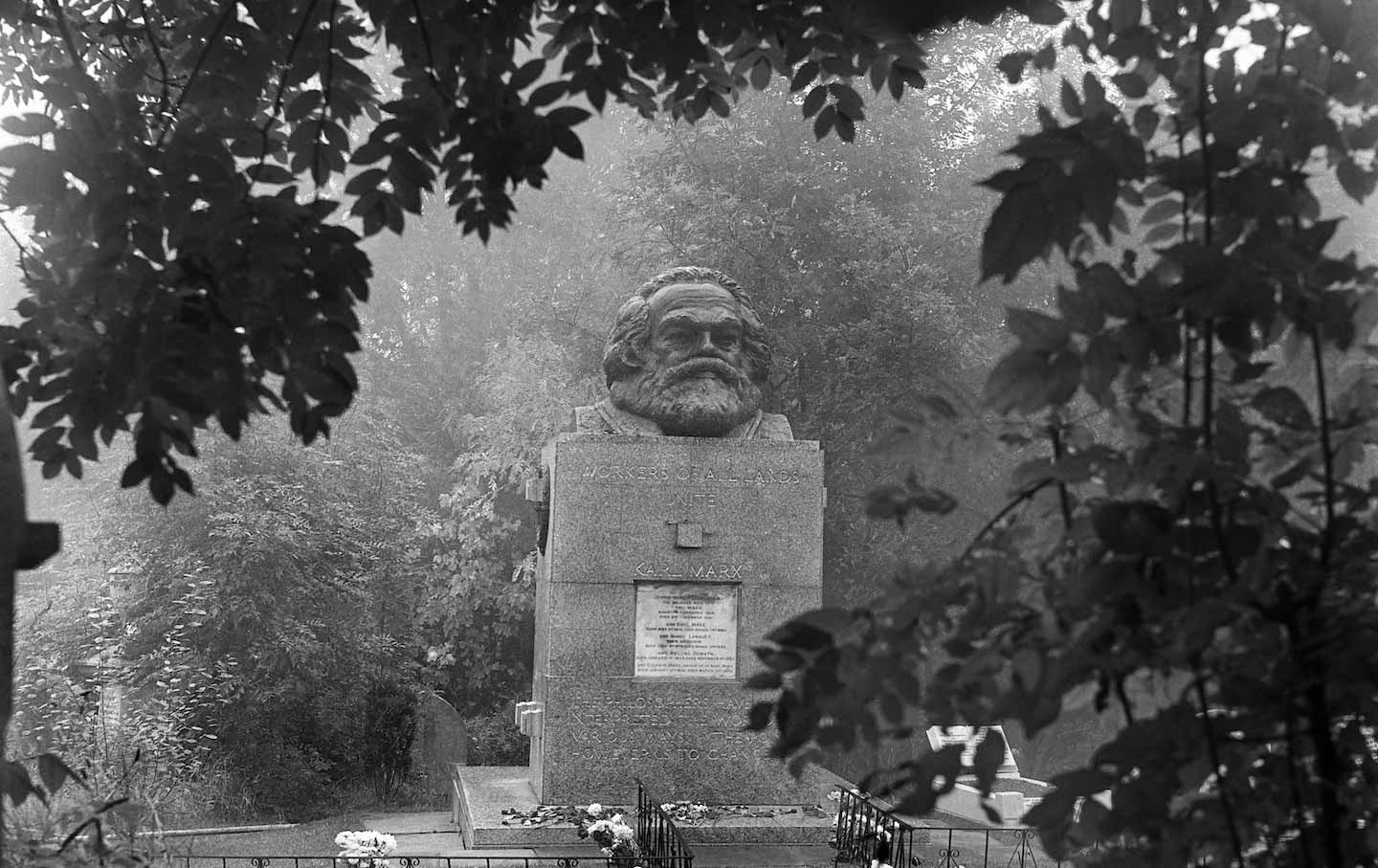

Tomb of Karl Marx at Highgate Cemetery in London, 1954.(Photo by English Heritage / Heritage Images / Getty Images)

Ask any two Marxists to define Marxism, and you will likely get at least three answers—with the added caveat, of course, that every definition must obviously be taken “dialectically.” A certain textualist tradition, one fixated on what Marx “really” thought, can take on puritanical and borderline zealous connotations. Instead, I think, McKenzie Wark is right that it is better to talk about the “Marx-Field” that Marx’s work enables, where various authors will pick up threads in his writing and apply or rework them as needed. Ironically, this irreverent approach always seemed more faithful to the spirit of Marxist dialectics.

Into the “Marx-Field” has stepped Søren Mau, a scholar based in Copenhagen, Denmark, and the editor of the venerable Marxist journal Historical Materialism. Mau’s recently published Mute Compulsion is largely based on his PhD research, which focused on Marx’s theory of power. Marx was perennially concerned with power, from his younger humanist days responding to illiberal authoritarianism in Germany to his mature work discussing capitalist domination. Despite this, he never offered a complete theory of power and domination. Like so many intellectual projects, Marx planned to write big volumes on dialectics, the state, and imperialism but never got round to it. A lot of us can relate.

Mau’s book takes its title from a lesser-known statement in Capital: Volume I that the “mute compulsion of economic relations seals the domination of the capitalist over the worker.” Mau follows Marx in claiming that “once capitalist relations of production have been installed,” one sees that “violence is thus replaced with another form of power: one not immediately visible or audible as such, but just as brutal, unremitting, and ruthless as violence; an impersonal, abstract, and anonymous form of power immediately embedded in the economic processes themselves.” While recognizably Marxist, it’s not hard to see the stamp of more contemporary analyses of power, like Foucault’s, which also take seriously the invisible ubiquity of (economic) power across society and nature. Distinguishing between coercive violence, ideology, and mute compulsion, Mau insists that the concept of mute compulsion plays a major role in the “social reproduction [of] capitalism” by establishing spheres of power where social life is subject to the influence of the economy.

Mau stresses how Marx’s critique of capitalism remained “unfinished” at the time of his death, leaving many important questions on the table. This means there’s a great deal left to do for those of us interested in carrying on his work. Unsurprisingly, Mute Compulsion is a meaty book that hopes to answer a particular question: What did Marx mean in saying that under capitalist conditions, “extra-economic immediate violence is still…used, but only in exceptional cases,” since in the ordinary run of things the worker’s dependence on capital will be enough to keep the system going? This isn’t an easy question to answer, but the most interesting questions rarely are. Over the course of 300 pages, Mau discusses how the Marxist tradition has tried to answer it, develops his own theoretical account, and then applies it to some contemporary issues.

Throughout Mute Compulsion, Mau rejects efforts by critics and defenders alike to reduce Marx’s work to crude economic determinism or even to characterize him as just another classical political economist writing in a critical vein. For Mau, what is distinctive about Marx’s analysis is not that it offers some deterministic “science” of history and society, in the sense of allowing us to make strict predictions about the imminent collapse of capitalism and its replacement by communism. Instead, following the tradition of “Western Marxists such as Korsch, Lukacs, Gramsci, Marcuse, and Adorno,” Mau is largely attracted to a more flexible kind of Marxist theory. This flexibility is apparent throughout Mute Compulsion: Mau stresses how domination by the economic power of capital can sometimes be brutally transparent, as when the state intervenes to break up strikes by actual workers but lovingly embraces legal fictions like “corporate personhood.” But the domination of economic power is generally far more subtle, since so many of the social transactions that make up daily life are defined by it. Indeed, the totality of this use of power seems naturalized, Mau argues, and it requires some demystification to see it in action.

Understanding how this mute compulsion of alienated social relations is exercised over us also helps us grasp why Marx—despite his many acidic comments about the excesses of the capitalist class and all—is not a utopian or a moralist. In the end, capitalists participate in the same totality as the rest of us, and they are often just as subject to the “tyranny of necessity” as the lower orders whose labor they command. In Mau’s terms, the class domination we see in capitalism is “impersonal,” since it isn’t this or that particular capitalist who ultimately dominates workers but rather capital itself. This is why it is so necessary to understand capitalism as an alien totality, rather than condemn it through pointing to notably bad capitalists.

This argument can seem a little bit rarefied when presented in theory-laden language, but it becomes very transparent in daily life. One of my first jobs was working at a grocery store as a cashier and cart boy. The owner of the store was actually a very nice guy, someone who went out of his way to make sure the workers felt respected and listened to. I’ll never forget the day someone came into the store with a bunch of pamphlets telling us to unionize. He was shown the door so fast you could hear the wind racing after him. After they kicked him out, management explained to us how unions might sound nice in theory but would make the store less competitive and lead to layoffs and trouble down the line. They pointed out how all our jobs depended on keeping prices low and sales high. What’s important to stress here is that nothing that management or the owner said was “untrue.” Our store was facing the (evil) new big-box grocery store that had opened up down the street. Allowing unions and increasing wages could very well lead to price increases and make the competition stiffer in exactly the way the powers that be described. But what wasn’t accounted for was the dialectical point that all of us—workers, management, owners, and competition—are dominated by the economic totality we are a part of.

These kinds of issues really come to the fore in the final sections of Mau’s book, where he writes about the influence of economic power and “power hierarchies” in the workplace. This involves being very critical of the “neoclassical economists” who, Mau claims, can “only understand power as a consequence of imperfect competition.” From a vulgar, neoclassical standpoint, there should be no problematic “power hierarchies” in capitalist workplaces, since every labor contract is a voluntary one between legal equals that can be ended at any time. By contrast, Mau argues, Marx described the capitalist as “the factory Lycurgus—a reference to the legendary lawgiver of Sparta—and his use of words like ‘despotism’ and ‘autocracy’ seems to suggest that the power of the capitalist is similar to the power of pre-capitalist rulers.” Anyone who has spent most of their waking life in a bad workplace—asking permission to go to the bathroom, being told how and when to talk to people, having your breaks and travel time for work go unpaid—knows there is plenty of truth to this characterization. The “freedom” available to workers isn’t much more than a choice between different flavors of despotism. The fact that this unfreedom is so frequently hidden by the language of choice is a testament to the mute power of capitalist ideology.

Mau’s book is, of course, a theory-heavy tome that would benefit from more historical and empirical content. This is somewhat ironic given that, in his mature works, Marx rarely wrote in a purely theoretical way, which is one of the reasons his account of power remained “unfinished” (along with dozens of other projects). But Mute Compulsion does succeed expertly in its goal of unpacking the often invisible forms that economic power takes under capitalist conditions.

The crucial question, then, is what would a society free from mute compulsion look like? Mau follows Marx in not having very much to say about this question, at least so far. In Capital: Volume III, the aging Marx talked about being liberated from the “realm of necessity” and entering into a “realm of freedom” by shortening the work day, “rationally regulating” our “interchange with nature” and bringing it under common control, and making the development of human powers an end in itself rather than a means to increase productivity and accumulation. This all sounds wonderful when taken at face value, but as we all know, the devil really is in the details. Nevertheless, Mau doesn’t need to have all the answers to show that contemporary capitalist life is riven by the kind of domination and alienation that belies all the rhetorical appeals to freedom that right-wing liberals and conservatives alike often make. As long as this contradiction persists within capitalist societies, there will always be a place for Marx, its greatest critic, and for new and exciting Marxists like Søren Mau.

Matt McManusMatt McManus is a lecturer in political science at the University of Michigan. He is the author of several books, including The Political Right and Equality and the forthcoming The Political Theory of Liberal Socialism.