The Uses and Misuses of Spinoza

The beguiling Dutch philosopher’s life and work is prone to misunderstandings and misreadings. A recent biography goes so far as to recruit him into the culture war.

Born in Amsterdam in 1632, Baruch Spinoza was the most original thinker of the European Enlightenment. Three and a half centuries later, his philosophy retains a sense of strangeness and novelty long exhausted in Descartes, Locke, or Voltaire. So distinctive was his thought that at a young age, before he had published a word, rumors circulated through the republic of letters about the Jew who was not a Jew but possessed an encyclopedic knowledge of the Bible along with a radical new method for reading it, and who had solved many of the metaphysical problems left behind by Descartes. At Spinoza’s country home in Rijsenburg, just outside of Leiden, and later in The Hague, figures like Christiaan Huygens, Henry Oldenburg, and G.W. Leibniz called on him to discuss his experiments in optics or to try and catch a glimpse of the long-rumored manuscript of his Ethics.

Books in review

Spinoza: Freedom’s Messiah

Buy this bookWith the publication of the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (1670), Spinoza’s quiet fame among scientists and philosophers turned into a vehement, Europe-wide notoriety and near-universal condemnation. A relentless, unprecedented assault on the tenets of the Abrahamic religions and on religious institutions more generally, the Tractatus was universally banned and reviled. Less incendiary but no less widely censored, the posthumous Ethics reimagined God as infinity itself, constructing an immanent univocal ontology (“monism”) in place of Descartes’s increasingly paradigmatic substantial dualism. Declaring that good and evil are nothing but judgments in the mind and that “virtue” is merely each individual’s sustained, rational pursuit of their own well-being, Spinoza espoused an ethical philosophy that was widely but falsely decried as atheistic and hedonistic.

“No philosopher was ever more worthy,” wrote Gilles Deleuze, the 20th century’s foremost exponent and interpreter of Spinoza, “but neither was any philosopher more maligned and hated.” Notorious throughout Europe by the end of his short life, in death the philosopher assumed mythic proportions and his biography became a conundrum, for every report and witness testimony agreed that this man, whose blasphemous ideas brought him an infamy normally reserved for tyrants and heresiarchs, was unimpeachably virtuous, living a modest, frugal, and kindly existence. No other philosopher since Socrates has been so persistently regarded as a paragon of the philosophical life.

For an intellectual of his era and reputation, little is known about Spinoza’s life. He left no diary; only one of his works, the unfinished “Treatise on the Emendation of the Intellect,” contains any biographical information. Like most of his peers, he maintained regular correspondences by letter, but only a fraction have survived; anything the generally circumspect philosopher did not destroy himself was carefully pruned by his literary executors, who preserved only “philosophical” epistles. A few defining events form the core of every account of him: his birth in Amsterdam’s Jewish community and his banishment from it; his retreat to the countryside, where he drafted the Ethics while grinding glass lenses; his extensive association with fringe Dutch Protestant groups. But there are entire years about which we know nothing.

Jonathan Israel’s Radical Enlightenment and its sequels (including a weighty biography of Spinoza published at the end of last year) showed that Spinoza’s books had wide distribution despite being banned, and that a surprising number of European thinkers who were not supposed to have copies of the books engaged quite deeply with their contents: Leibniz, Hume, and Kant are just a few of the major figures who attacked Spinoza while bearing the obvious marks of his influence. For most readers, however, knowledge of Spinoza came secondhand, from vituperative reports written by furious clergy and indignant professors, and from biographies that were popular but significantly unreliable.

Every early account of Spinoza’s life and thought presents the Jewish community he was exiled from as benighted, superstitious, and medieval in comparison with its mostly Dutch Calvinist surroundings, which existed on the cusp of the Enlightenment in a de facto state of “toleration.” The assumption that the encounter with gentile philosophy spurred him on his path of apostasy neatly explains the otherwise difficult problem of Spinoza’s banishment: In this story, it was rationality itself that made the Jews of Amsterdam tremble in fear and loathing as much as any particular dogma Spinoza may have espoused. In Pierre Bayle’s account, “the rabbis” feared Spinoza enough to send hired daggers after him post-banishment—an unlikely story. (My own best guess is that the great philosopher probably just got mugged.) This image of Spinoza, and of his relationships both with Judaism and with his post-exilic Christian environment, remained consistent and dominant well into the 20th century; as late as 1935, Paul Hazard described Spinoza as “a Jew, but a Jew despised by the Ghetto.” The narrative of the philosopher’s banishment proved irresistible to later Protestant thinkers. Spinoza was permitted his place in the canon of the Enlightenment not least because he offered proof that both Catholicism (through the Inquisition) and Judaism (through banishment) would chew up and spit out those who offered the promise of rationality and free thought.

In 1899, Jakob Freudenthal published the first critical biography of Spinoza, collecting every available historical document and initiating a scholarly and archival renaissance. Extensive and previously unknown information about the philosopher’s family, education, and finances, as well as a copy of his writ of banishment, were found in the Amsterdam archives in the following decades. In the 1940s, Israel Revah found previously unknown reports about Spinoza and his circle written by Spanish visitors to Amsterdam shortly after the philosopher’s banishment. Along with a great influx of new research on the history of Spanish and Dutch Judaism, these developments not only gave us valuable new biographical details but also significantly transformed our understanding of the philosopher’s origins and youthful context.

Hardly a “Ghetto,” the Sephardic community of 17th-century Amsterdam was a dynamic and generally prosperous group of recently reconverted Jews who served as a crucial cog in the rapidly expanding economic machinery of the Dutch Golden Age. Spinoza’s milieu was the first generation born in the United Provinces, and like most of his peers he grew up well-educated and multilingual. Neither resistant to new ideas nor trapped in medieval superstition, Spinoza’s community offered advanced Talmudic study for its most promising pupils but also a range of study and discussion groups. Spinoza’s own father probably paid for his Latin tutor.

We also know now that Spinoza acquired significant skill in philosophy before he left the Jewish community, and probably long before he read Descartes. In early accounts and in quite a few today, “Jewish thought” means rabbinical Talmud study (halakha) and sometimes Kabbalah. The existence of a separate Jewish Aristotelian tradition, a tradition often directly hostile to Kabbalah, was largely unknown, and it was easy to assume that Spinoza’s strange and unprecedented system was simply Cartesian philosophy filtered through an unspecified Jewish lens. This position is exemplified by Hegel, who was both obsessed with Spinoza and highly critical of him; in the lecture on Spinoza in his Lectures on the History of Philosophy, Hegel writes that “the dualism present in the Cartesian system is decisively abolished by Spinoza—as a Jew.” The idea that Spinoza was a strange offshoot in an emerging European movement and not the acme of a long and rich pan-Mediterranean tradition goes hand in hand with the centuries-long disavowal on the part of Western scholars of the profound and sustained influence of Muslim and Jewish philosophy on European thought in the medieval and early modern periods.

Carefully and slowly, to a significant degree through the work of Jewish scholars, centuries of myth and prejudice around Spinoza’s life, thought, and environment have been unpeeled. And now comes Ian Buruma’s new biography, Spinoza: Freedom’s Messiah, determined to undo a century of progress in Spinoza studies and rebuild some of the most tired myths around the philosopher and his ideas, valiantly reiterating these retrograde perspectives in the face of much new evidence to the contrary.

“I should come clean about my own interest in this extraordinary thinker,” Buruma writes in the first chapter.

I am not an expert in philosophy and cannot presume to offer fresh insights into Spinoza’s thinking…. But when I was asked to write about Spinoza, my curiosity was piqued first because intellectual freedom has once again become an important issue, even in countries, such as the United States, that pride themselves on being uniquely free. If one thing can be said unequivocally about Spinoza, it is that freedom of thought was his main preoccupation.

As it happens, Spinoza’s main preoccupation was philosophy. His magnum opus was the Ethics, carefully compiled and revised over decades; in a letter to Oldenburg from 1665, he writes that only the exigencies of current events led him to pause work on “my Philosophy” to address political and social questions. Buruma’s book is for the most part a précis of Steven Nadler’s Spinoza: A Life (1999), though he does throw in some invented details from less reliable biographies for good measure. While Nadler, in a recent 2018 edition, incorporates the bulk of the new material discovered in recent decades, he generally downplays Jewish intellectual traditions in favor of Spinoza’s Dutch context. Buruma picks up on that inclination and runs with it. Very briefly touching on a now-massive body of 20th- and 21st-century scholarship, he notes that “more serious attempts have been made to put Spinoza in a specifically Jewish light,” blithely judging that “some of these claims might seem farfetched, even a bit zany.” Later, when Buruma finally mentions possible Jewish sources of Spinoza’s thought, he notes that “Nadler mentions two…Maimonides’ Guide to the Perplexed…and Judah Abrabanel’s Dialogues on Love.” Which Jewish thinkers Spinoza himself cites as forebears Buruma does not seem to know. As it happens, there is at least one significant and unfortunate omission in Nadler’s list.

A great deal of the book is eye-rollingly familiar. There are paeans to the many goyim, like Goethe, whom Spinoza’s unique not-Jewish Jewishness helped guide towards personal enlightenment. There is the popular but unfounded claim that Spinoza was the “nemesis” of the community’s rabbi, Saul Levi Morteira. There’s the assertion that “Spinoza was a good enough student to attend yeshiva…where he acquired sufficient knowledge to become a daring critic of biblical texts.” But among the most surprising discoveries made in the archives of the Amsterdam community in the last century were enrollment lists for Morteira’s “yeshiva-level” classes. Spinoza’s name is not on the list for any of the years he could have enrolled in the classes, strongly suggesting he did not have rabbinical training. It’s easy to understand the enduring appeal of an oedipal drama in which Spinoza was first trained by Morteira and then betrayed him, but there’s little evidence for it.

Spinoza’s philosophy fares even worse in the book than the details of his life. Buruma confidently snarks that “like most Marxists, who have only a glancing knowledge of Das Kapital, Spinozists were not necessarily careful readers of Spinoza’s books.” The people I know who take Marx seriously tend to be pretty diligent readers of his work, but I have discussed and taught the Ethics often enough to know when I’m listening to someone who doesn’t know the text. There is no systematic discussion of Spinoza’s philosophy, and the casual asides that replace it, scattered throughout the text, are not just weak; they are simply wrong. Spinoza does not see “God as the embodiment of nature”; to state that “everything emanates from God” is to fundamentally and completely misunderstand Spinoza’s ontology, which is immanent, not emanationist. (In Spinoza, God is all things, as opposed to God being a higher order of being from which all things emanate.) The repeated insistence that intuition and reason are opposites shows a profound misunderstanding of Spinoza’s epistemology and his concept of truth. For three and a half centuries, great thinkers from Leibniz and Hume to Marx and Nietzsche have found Spinoza’s metaphysics as fascinating as it is nearly unfathomable, but fortunately Buruma can tell you what it all means with enough space left over for a nice long rant.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →A scholarly book’s critical apparatus should do at least two things: It should show expert readers that the author knows what they’re talking about, and it should allow interested novices to follow the trail of citations back to the texts being cited. Buruma’s does neither. Anyone who has ever written or graded a hastily cranked-out term paper will recognize a number of the authorities Buruma cites, among them “some believe,” “many believe,” and “various scholarly opinions.” A sentence like “Spinoza wrote that Jews might one day found their own state once they had rid themselves of their religious prejudices” demands a reference to a passage in Spinoza’s own words. Where did he write that? The reader of a scholarly work simply must be able to track a statement like this back to the source.

None of this really matters, though, because Buruma doesn’t actually care about Spinoza that much. The best available evidence, patiently explained in several books he cites, is incompatible with the story he wants to tell about the transhistorical struggle of rational free thought against religious (or “quasi-religious”) benightedness. It all comes bubbling to the surface in a belated but entirely unsurprising screed that makes up most of the final chapter, “Spinozism,” ostensibly a survey of the philosopher’s postmortem influence. Here, even the thin pretense of sourcing and rigor is abandoned for a spumy explanation of why insisting on “lived experience” as a fundamental factor in your conception of the world is the same as being fascist, basically:

Creating their own reality is what totalitarian states do. They impose what people should think of the past, present, and future. But the right-wing attack on truthfulness echoes views promoted by some critics on the left. That people create their own reality is also the assumption of “progressives” who believe that all truth is but the reflection of relative power.

Buruma quickly follows this up with another brazen statement: “The insistence…on ‘lived experience’ as an essential condition of truth—that truth cannot be objectively acquired, let alone expressed, but is the property of a particular race or gender—is too close to the völkisch ideal for comfort.”

Predictably, Buruma’s other exemplary instance of “creating your own reality” is transness, evidently the most pressing political problem he can think of on which Spinoza’s thought might be brought to bear in the present. “Some people born in a male body feel trapped in the wrong gender and wish to live as women. One can respect this feeling without abandoning the biological truth that there are discernable differences between male and female bodies.” To paraphrase a popular contemporary meme, none of those words are in the Ethics.

It’s certainly possible to borrow arguments, concepts, and frameworks from much older texts to address contemporary questions and issues that those authors never could have imagined in their wildest dreams. This possibility is in fact the implicit condition of our continued collective scholarly engagement with the history of philosophy. But that requires work. What we see here is merely a lazy attempt to drape trite contemporary bigotries over a brilliantly unique 350-year-old corpus. We can give Buruma credit for one thing, though: He tells us early in the book that he won’t provide “fresh insights into Spinoza’s thinking,” and he sticks to his word.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks

The late actor and director leaves behind a roster of classic films—and a much safer and juster California.

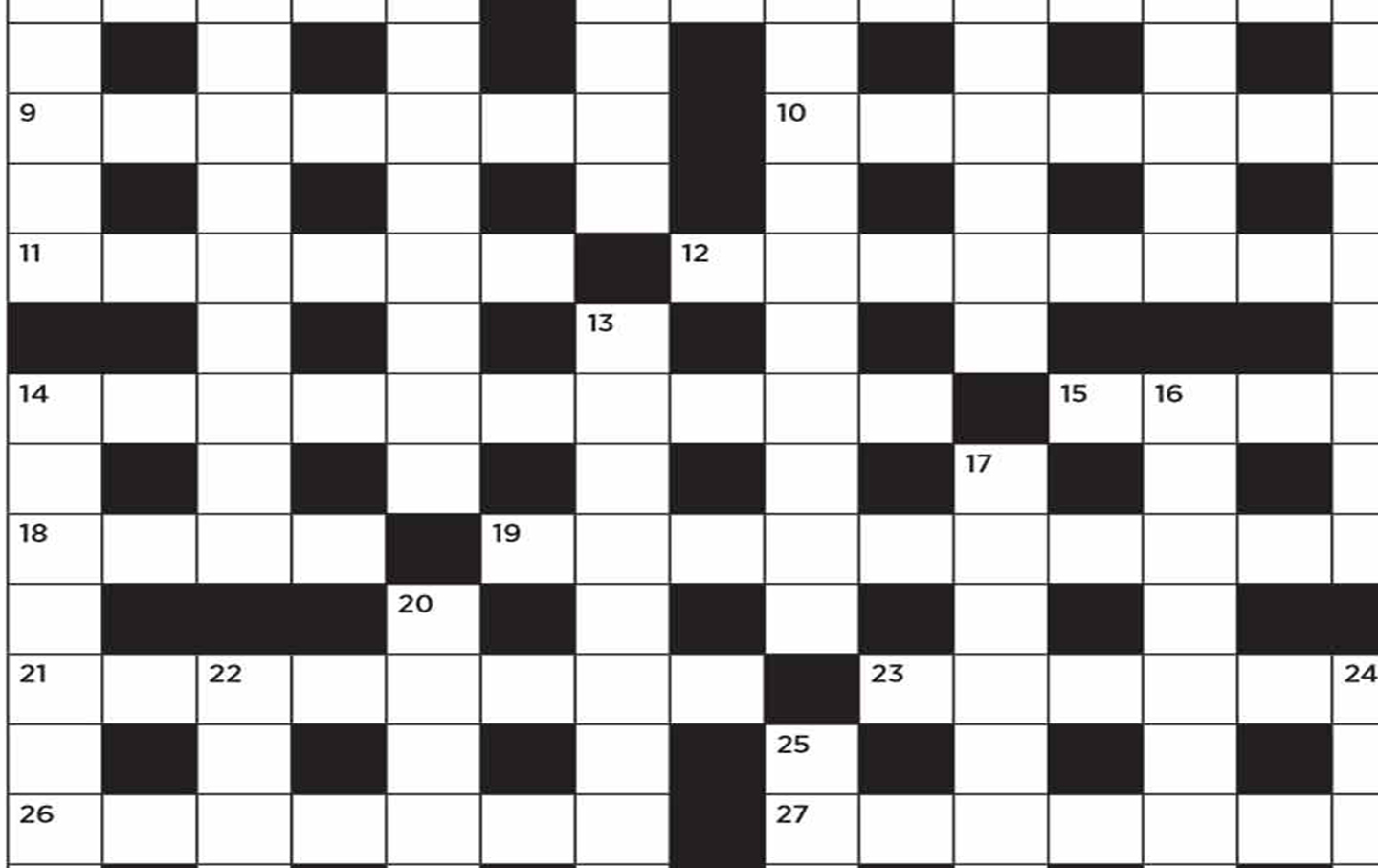

Solution to the “Big Event” Crossword Solution to the “Big Event” Crossword

If questions remain after reading this, please write to sandy @ thenation.com.

Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments

Dev Hynes moves between grief and joy in Essex Honey, his most personal album yet.