In early June, there was an intense outpouring of grief from the many friends of the cartoonist Ian McGinty, known for his work on winsome manga-inflected children’s comics such as Welcome to Sideshow and Adventure Time, who passed away unexpectedly at the age of 38. Private mourning can sometimes explode into public anger when a death is resonant with larger problems. The world of comic books and graphic novels, like Hollywood and television in this era of labor strife, is one of many cultural industries where anger at shoddy working conditions has made nerves raw. As Chris Kindred reported in The Daily Beast, an angry tweet by fellow cartoonist Shivana Sookdeo provoked debate that “soon took on a life of its own as industry novices and veterans alike began commiserating over the labor conditions that colleagues have speculated contributed to McGinty’s passing. Their stories of long hours, frequent burnout, and chronic illness were filed under the hashtag #ComicsBrokeMe, illuminating for the wider public how dangerous the comics industry has become.”

Writers as distinguished as Neil Gaiman—the mastermind behind the Sandman series—joined the fray and agreed with the consensus that comics is an exploitative industry marked by multiple forms of precarity: declining incomes, pervasive use of freelancers instead of paid staff, and little health care. “How anyone survives on current page rates leaves me chilled,” Gaiman reflected.

But if comics are breaking people now, they have been doing so for a long time. The American comic book industry was created in the 1930s by figures like Harry Donenfeld and Jack Leibowitz, early powerhouses at DC Comics, who were one degree away from being gangsters. With a background in bootlegging and “racy” semi-pornographic pulp magazines, the foundational comic book publishers ran low-rent, fly-by-night operations, with little scruple about granting any more rights to cartoonists than they had to.

Multiple participants in #ComicsBrokeMe cited the long litany of victims of publishing predation: Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel, who sold Superman for a song to Donenfeld and Leibowitz, ending up in penury for much of their adult lives, until DC Comics was shamed into giving them a modest pension; Bill Finger, the cocreator of Batman, who sank into alcoholic bitterness because he received neither credit nor royalties for the character; and Steve Ditko, the cocreator (with Marvel editor Stan Lee) of Spider-Man and Dr. Strange. Ditko died in 2018 and his estate is currently suing Disney (the owner of Marvel) to recover claims on those characters.

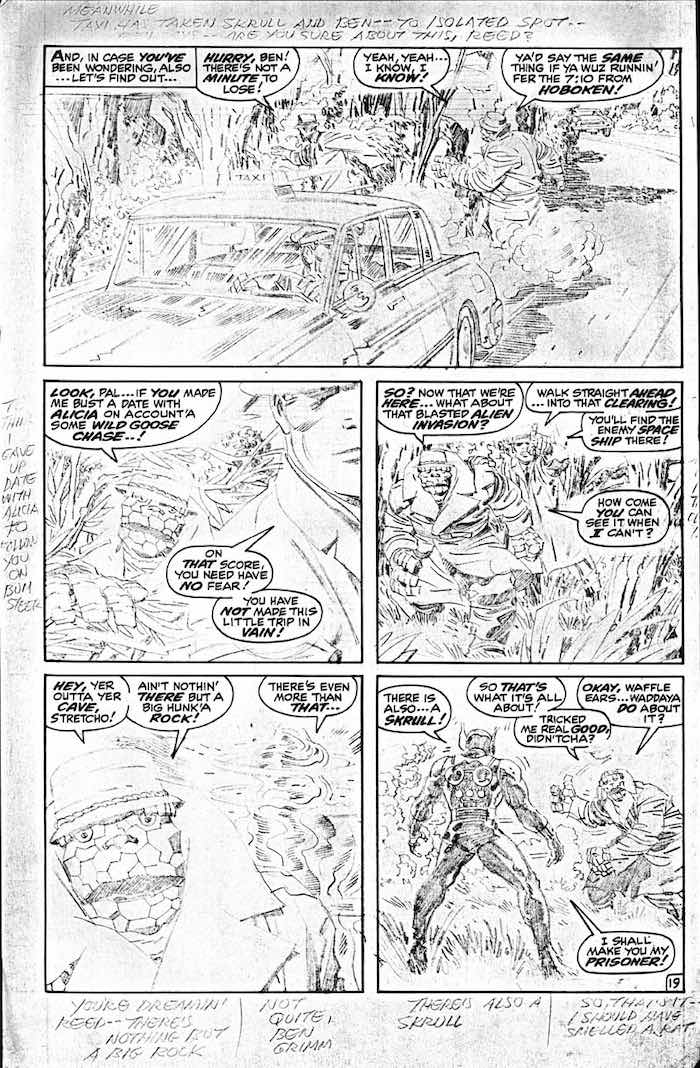

Above them all stands the Promethean figure of Jack Kirby, one of the most fertile and imaginative artists of the last century. Kirby died in 1994. In 2014, Kirby’s estate settled with Disney, so Marvel now acknowledges that he was cocreator (with Joe Simon) of Captain America and (with Stan Lee) of the Fantastic Four, the Hulk, Thor, the X-Men, Black Panther, and many more. As Kirby’s son, Neal Kirby, recently recalled, “My father worked at home in his Long Island basement studio we referred to as ‘The Dungeon,’ usually 14–16 hours a day, seven days a week…. Through middle and high school, I was able to stand at my father’s left shoulder, peer through a cloud of cigar smoke, and witness the Marvel Universe being created.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Out of Kirby’s labors in the 1960s in the Dungeon emerged characters that would gain global fame—and make billions in profit for Marvel and Disney. Kirby only ever earned a freelancer’s middle-class income for his trouble; he never got royalties. Thanks to the 2014 settlement with Disney, his children have a better deal. But even as the lawsuits of Ditko and other colleagues make their way through the courts, the struggle over Kirby’s legacy isn’t over. Despite the 2014 settlement, Disney and Marvel are backtracking on their acknowledgement of his contributions.

On June 16, just as the fury of the #ComicsBrokeMe conversation was reaching a crescendo, Disney released the documentary Stan Lee. Directed by David Gelb, this is a work of corporate propaganda designed to promulgate the idea that the Marvel superheroes were primarily the creation of Lee in his capacity as editor, with artists like Ditko and Kirby merely carrying out his vision.

This claim is false. It has been proven false not just through interviews and essays by artists like Kirby and Ditko (along with other figures like Wally Wood and Gil Kane). It is also belied by a mountain of research into the comics archives, particularly the original art, which shows how the artists came up with storylines and preliminary dialogue—to which Lee added a layer of polishing and rewriting. Over the last few years, the Lee version of history has been debunked by journalists and scholars such as Abraham Josephine Reisman, Sean Howe, and Michael Vassallo. Yet Disney still pretends that the old legends are true.

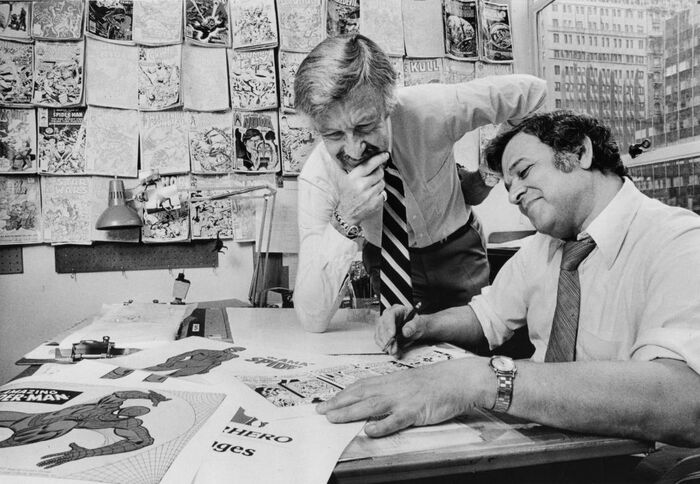

Lee’s self-promotion often gets chalked up to egotism. But there is an economic motive that is perhaps more important than his undeniable tendency to peacock. Lee joined Marvel Comics (then known as Timely) in 1939 at the tender age of 17. Starting as an office boy, he was elevated in less than two years to being an editor. The fact that he was related to publisher Martin Goodman (whose wife was Lee’s cousin) helped. But, beyond nepotism, Lee proved supremely useful to Goodman and future owners of Marvel because he stood as a shield against claims by freelancers. If Marvel could claim that Lee, as editor, was the creator of their work, then freelancers had no rights. Aside from a few bumpy years later in life, Lee maintained ties with Marvel till the end. When Marvel was fighting Kirby in court, they had Lee as their prize witness.

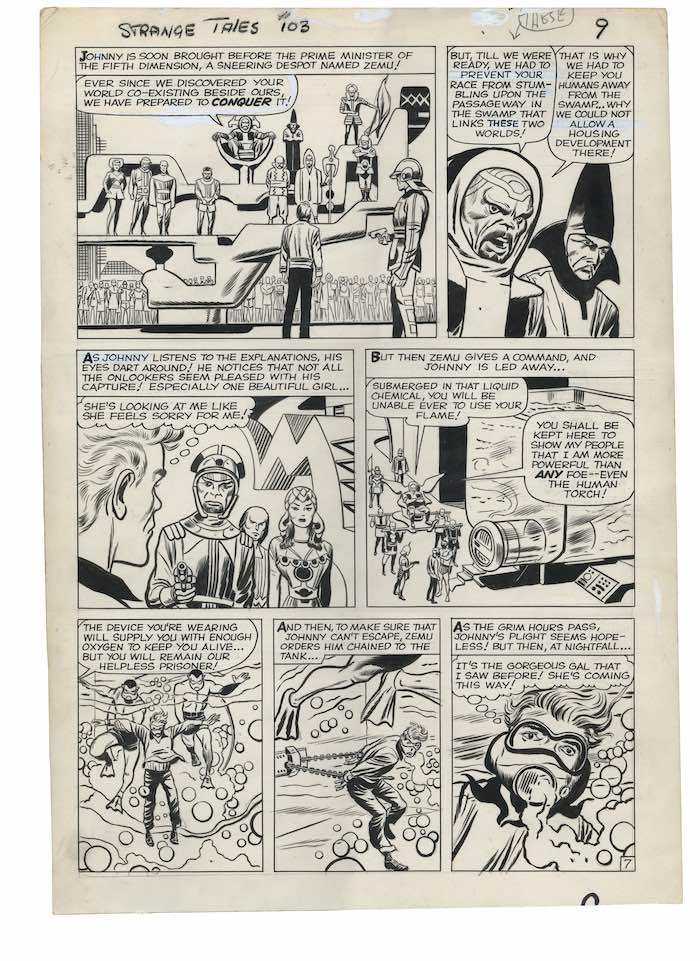

But Lee’s version of history is a pack of lies. Consider two famous creations: the Fantastic Four and Spider-Man.

In a 1998 interview with Comic Book Artist, Lee offered this story: Goodman came to him and said, “I’ve been playing golf with Jack Leibowitz. Jack was telling me the Justice League is selling very well, and why don’t we do a book about a group of super-heroes?” Lee added, “That’s how we happened to do the Fantastic Four.”

In a recent article in TheNew Yorker, critic Michael Schulman credulously recirculated this fabulation as fact. According to Schulman: “In 1961, [Martin] Goodman was playing golf with DC’s publisher and learned that its heroes would soon appear together in The Justice League of America. Goodman told [Stan] Lee to copy the supergroup concept, and Lee and the artist Jack Kirby issued Fantastic Four No. 1.”

Les Daniels, who interviewed Liebowitz for his 1995 book DC Comics: Sixty Years of the World’s Favorite Comic Book Heroes, says the golf story is “industry legend.” Daniels quotes Liebowitz as saying, “I’m sure I didn’t discuss anything with him about that.”

DC publisher Irwin Donenfeld, son of company founder Harry Donenfeld, has also weighed in. In 2001, Donenfeld took part in a panel discussion at the San Diego Comics Convention. A member of the audience asked about the golf story. Donenfeld responded, “I read that in one of the books. Never happened.”

In 1999, Mark Evanier, a former Jack Kirby assistant who has written a book on Kirby, wrote that he had seen a deposition by Goodman denying the golf story. (Evanier is a frequent expert witness on lawsuits over intellectual property between Marvel artists and the publisher.) The golf story and other Lee tall tales are investigated in depth in Michael Hill’s book Kirby at Marvel.

Everyone who is a position to have gone to the golf game denies that either the game or the conversation Lee describes took place.

The golf game is not just a colorful fib; it’s also a convenient fiction designed to challenge a counternarrative that would be costly to Marvel.

Jack Kirby has a very different version of the Fantastic Four origin story. He claims that the idea for the comic was one of many he took to the publisher as a freelance writer/artist. Kirby’s claim has credibility—especially given his early career. From the late 1930s onwards, he was a pioneer who created many new characters and concepts, often with his partner, Joe Simon. Simon and Kirby created Captain America, The Boy Commandos (a bestseller during World War II), and the pace-setting Young Romance (another bestseller that created the romance comics genre).

In particular, Kirby had a record of creating teams of adventurers, usually numbering four or five. These teams would often have two characters that were polar opposites: a roughneck urban brawler and an egghead intellectual—the pattern replicated in the Fantastic Four with the Thing and Mr. Fantastic. In 1956, Kirby created a popular series for DC Comics known as Challengers of the Unknown, which is a particularly close prototype for The Fantastic Four: Both series feature space-age adventurers united by a shared trauma (a near-death plane crash for the Challengers, a near-death radiation-tinged rocket crash for the Fantastic Four). Both series have a sci-fi bent, with stories of rocketry, time travel, and aliens. Both series feature the dichotomy between the egghead and the roughneck. The plots of both series are strikingly similar—because one man, Jack Kirby, created both.

In fact, Kirby created many prototypes for the Fantastic Four. There was no golf game. But in 1961 Kirby went to Marvel with a new variation of an idea he had worked on before.

In the documentary, Lee claims that he created Spider-Man after seeing a fly on the wall. Explaining his dispute with Ditko, Lee said, “Steve had complained to me a number of times when there were articles written about Spider-Man which called me the creator of Spider-Man, and I had always thought I was, because I’m the guy who said, ‘I have an idea for a strip called Spider-Man.’”

Again, conflicting testimony by cartoonists and the historical record belies these claims. Simon and Kirby toyed around with insect-themed superheroes in the 1950s, creating a proto-Spider-Man and also a character called The Fly, which was published by Archie comics in 1959. Kirby claims that in the early 1960s he took a version of this idea (then called Spiderman) to Lee, who in turn showed it to Ditko. Ditko suggested major modifications to both the costume and characterization.

In 2007 in a small-press publication called The Avenging Mind, Ditko dryly noted that Lee was a master of “creative crediting,” which allowed him to “unfairly upgrade him and downgrade others in what they did.”

Aside from individual acts of creation, the production method at Marvel argues against Lee as primary creator. When working with artists like Kirby, Ditko, or John Romita (who took over Spider-Man after Ditko), Lee would offer minimal plot suggestions. The artists would then plot the story and fill the margins of their drawings with dialogue suggestions (or write dialogue suggestions on a separate page).

None of this is deny that Lee played a significant role at Marvel. He was a gifted editor and talent scout, and the dialogue and captions he added had a distinctive hip and jocular voice that helped to knit the Marvel Universe together. But he was never the sole creator, which is the lie the Disney documentary insists is history. It’s a useful lie for Disney. If one staffer created everything, the IP remains secure. As such, the exploitation by Marvel in the 1960s remains a model for Hollywood today.

The fact that Disney is regurgitating this mythology in 2023 shows how deeply rooted historical exploitation in the comic book industry still is. Comics remains a predatory industry, and Stan Lee—even after his death in 2018—remains the avatar of corporate mistreatment of workers.