Taylor Swift, Poet

Country singer, globetrotting pop star, and now melancholic poet—Taylor Swift has offered her listeners almost everything.

By any reasonable metric, Taylor Swift has done everything any listener, critic, or fan could ask, and not just once but over and over and over again. Since she first became famous as a country star in her teens, Swift has evolved musically and lyrically; has shown that she can work on her own and with various collaborators; has given us bops and dance hits and introspective numbers—breakup songs and love songs, get-well songs and good-advice songs. Swift has learned from R&B artists and producers without trying to duplicate their glories, and from stripped-down 2000s indie without trying to copy its edge.

She has written (and cowritten) phrases that have traveled the world and given new life to former clichés.

Swift has also found ways to carve her own path, both economically and creatively, and to make or keep her work hers, at junctures where other artists have lost control. She has kept her fans close, stoked their curiosity, and taken control of her business as well as her creative life. She has learned choreography, costumes, and set design, and worked brilliantly with people who do those things; from an uncertain start as a live performer, she has become a dynamic figure onstage, singing and dancing for three-plus hours straight. And along the way, she has dominated the pop charts so thoroughly that other artists get locked out, unless they appear in her songs. She has even, in the Kansas City Chiefs’ superstar tight end Travis Kelce, found an apparently supportive, devoted partner.

So then why does Swift feel so bad? What kind of frustration or grief has placed her among the “tortured poets” on her latest album, or given her the right to critique them? It’s not a fair question: Money can’t buy happiness (though poverty may preclude it). But it is one that shadows The Tortured Poets Department, which is certainly her saddest record. Of the 31 tracks, I count only three about connections that do not come apart or fail. The first one, “Robin,” addresses her cowriter Aaron Dessner’s young son. The other two could be addressed to Kelce: “The Alchemy” piles up flirtatious football puns, while “So High School” sets its enthusiastic declarations over rapt shoegaze guitar: “I feel so high school every time I look at you—but look at you!” Swift repeats that last phrase while switching its meaning; literary critics (like me) call that device syllepsis. Swifties (also like me) call it fun. And yet the rest of the songs on the album address pain and hurt. Men betray her. Fame feels hollow. Obscurity beckons. Spotlights demand escape. Promises crumble like cities besieged. And Swift struggles to find a way to save herself.

Swift has called Red (2012) her only “true breakup album.” Her new one tells breakup stories—long, sad stories—too, but it has no single kind of story; instead, it feels more like three braided together. One—call it the A-plot—unravels a years-long romance with a boyfriend whose chronic depression Swift (or someone much like her) cannot assuage. Regretfully, eventually, she walks away. “So Long, London” anchors this plot, with its wary, twitchy, continuous triplets slicing a standard pop 4/4 into 12 equal low notes (aka 12/8 time): “I stopped trying to make him laugh, stopped trying to drill the safe… / And I’m pissed off you let me give you all that youth for free / For so long, London.” The song’s bridge (a London bridge?) adds, emphasizing the singer’s American-style r’s: “It isn’t right to be scared / Every day of a love affair… / When you’re not sure if he wants to be there.” Swift-watchers can associate this material with her real-life boyfriend of six years, the camera-shy British actor Joe Alwyn.

Another story—call it the B-plot—begins in the aftermath of that long romance. What to do once you’ve fled a life so grimly and insistently domestic? You look, if you can, for its opposite: an irrepressible drama king, a ball of energy, even a tortured poet. Swift appears to have found that guy in Matty Healy, who leads the pop group the 1975; she and Healy appeared together for a month or so in early 2023. Something like their relationship animates the album’s B-plot, which encompasses head-over-heels devotion (“But Daddy I Love Him”), grinding desolation (“Down Bad”), and the harshest, most dismissive, most condemnatory song that Swift has ever written about anyone, “The Smallest Man Who Ever Lived.” It’s easy to imagine Alwyn going out in London after this album sinks in; it’s harder to see Healy showing his face anywhere in public again.

Yet a third story—the album’s C-plot, and the one on which the others rest—follows no single romance, or hookup, or breakup: It’s about pressure and fame and Swift’s own need to perform. “Beauty is a beast that roars, down on all fours, / Demanding more,” she purrs in “Clara Bow,” over stark bass, and Swift—“a pathological people pleaser,” as she sang on “You’re Losing Me”—shares that hunger, cannot stop feeding that beast. The Taylor Swift we meet on The Tortured Poets Department needs to be seen, fears vanishing under the water or below the ice (see “The Bolter”) if she’s not heard and admired, and yet she knows that the strain of constant performance could destroy anyone, even her. “But Daddy I Love Him,” up-tempo and sweet and sour, treats her chaotic romance (evidently with Healy) as a poke in the eye to judgmental fake fans, “Sarahs and Hannahs in their Sunday best”: “I’m having his baby! No I’m not, but you should see your faces.” Rhetoricians call that sudden turn toward the audience apostrophe; Swifties, called out for our prurience, may turn red.

Yet the secret to this story comes in “But Daddy I Love Him” too: “Growing up precocious,” Swift admits, “sometimes means not growing up at all.” How does it feel to receive, from such a young age, such great rewards for being and doing what other people expect? (Swift was born in 1989; her first album came out in 2006.) How does it feel to become a public symbol of pop success or romantic distress (see “The Prophecy”)? Can she ever stop? But how can she go on?

This C-plot emerges through songs that take place after a romance ends. It’s the story of “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?” and the story of “I Hate It Here,” a melancholy, self-accusing number whose offhand observation about historical racism obscures its real point: “Nostalgia is a mind’s trick,” and there’s no time like the present for facing your demons. The same story animates “Florida!!!,” a high-tension tune about swampy imagined escapes: “Your home’s really only a town you’re just a guest in.” The phrase rhymes with “Destin,” the beach town near Pensacola; it also points to the rough parts of life on the road.

The Swift who chairs The Tortured Poets Department, and who showered social media with clues about its content, needs our attention, if not our approval. And it’s not easy to write, let alone perform, the kind of art that Swift seems driven to make: confessional and exposed, intimate and serious, and yet fully aware of its global audience, of the girls and women and even men watching and listening. This precocious (she uses that word twice on the new album) child grew up to depend on her talent, and not just for money (she could retire tomorrow) but as a way to inhabit her life.

That life demands its own kind of acting—and, Swift declares, “I can do it with a broken heart.” The song by that title offers a dance track nearly worthy of Dua Lipa or Erasure, equal to anything on Swift’s 1989. Its glittery, arpeggiated chorus tells us what we cannot see from the audience, no matter how close we get to the stage: “I’m so depressed, I act like it’s my birthday… every day.” Each declaration overspills its measure, in what poets call enjambment. “I cry a lot, but I am so productive… it’s an art. / You know you’re good when you can even do it… with a broken heart.” Who hasn’t had to perform on a bad day at work? But who else has had to do it on Taylor’s scale? It’s a song so exhilarating, and exhausting, that after two verses it just stops: “I’m miserable,” Swift exclaims, not singing, just speaking. “And no one even knows! Try and come for my job.” Live on the Eras tour, she delivers those last six syllables differently: not an aside, but an emphatic, on-the-beat rebuke.

As much as The Tortured Poets Department can split up into three plots—depressed boy, chaotic boy, precocious girl—it also can also cleave sonically in two: synth-heavy songs, like “Broken Heart” and the title track, most cowritten with Jack Antonoff, and songs driven by acoustic guitar or piano, most cowritten with Dessner. The majority of these songs (though not “Clara Bow” or “So High School”) resemble in texture and instrumental timbre some slice of Swift’s earlier work. These reprises amount to features, not faults; they let Swift vary, elaborate, and experiment with her words and her voice, which reaches almost screechy soprano levels in “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?” and scrapes the bottom of her already low alto—while keeping up with a 7/4 time signature!—in “The Smallest Man Who Ever Lived.”

More than merely testing her vocal range, though, Swift stretches out and reaches new heights as a writer: not as a print-based poet like Dylan Thomas (whom the title track name-checks), but as a writer as good as anyone alive at placing inventive, evocative language into pop melodies designed to be sung. Besides syllepsis and apostrophe, there’s adianoeta, hyperbole, epitrope, even zeugma (one verb used two ways): “You crashed my party and your rental car.” And, constantly, there’s the vowel rhyme that works in songwriting but rarely in books of poems, deployed for variety and for surprise. Near the end of “Peter” (one of five songs without a cowriter), Wendy tells Peter Pan, “Please know that I tried to hold on to the days when you were mine / But the woman who sits by the window has turned out…” What would you expect to follow “turned out” and rhyme with “mine”? Maybe Wendy turned out “just fine”? But no: “The woman who sits by the window has turned out the light.”

Swift’s confident extravagance with words fits a figure who cannot get enough: not enough reassurance, not enough support, not enough applause or praise or positive feedback, to hold back permanently the sense that she’s worthless, or hollow, or doomed to be unlovable (see, again, “The Prophecy”). Each award, each No. 1 album, helps—but then the void returns. After all, it was the Taylor of several months ago who entertained a dying child in Sydney (look up “Scarlett Oliver”), and the Taylor of 12 years ago who got us all dancing to “22” and helped us dump no-goodniks with “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together.” What has she done lately? What if she’s done all she can, all she will ever do?

Some of us know this feeling as impostor syndrome. Others—including the Taylor Swift who sang “Nothing New” with a younger Phoebe Bridgers—might hear in it a fear of growing old. Readers of this magazine may see in it an aspect of capitalism, with its insatiable demand for new and greater returns. (“I Can Do It With a Broken Heart” even includes a literal crowd shouting “More!”) The economist Joseph Schumpeter wrote of the “fundamental impulse that keeps the capitalist engine in motion,” the need to create new stuff to meet new demands: Such a way of life, he concluded, “not only never is but never can be stationary.”

In this sense, Swift —who famously induces fans to buy more and more records—comes across as an engine of capitalism, its creation but also its victim. Her participation in the world economy, her ability to give us product, to produce the feelings we demand, becomes part of her identity. And yet the songs themselves—“I Can Do It With a Broken Heart,” “Florida!!!,” “Cassandra”—depict a neediness less systemic than characterological and existential, what the 18th-century critic Samuel Johnson, in his novel Rasselas, called “that hunger of imagination which preys incessantly upon life, and must be always appeased by some employment.” Johnson was describing the Egyptian pyramids, though he could also have been thinking about his own incessant drive to talk, and write, and not be alone. His depression, too, worked the graveyard shift.

The Tortured Poets Department offers heartbreak and recovery, acidity and sweetness, toughness and fragility, foreknowledge (“Cassandra” again) and naïveté. But its A, B, and C plots, its glossy, radio-ready hits and stark piano songs, together depict a scary need for more, both on the part of the artist and on the part of an audience that does not want her to step into the same spotlight twice. That’s who she is, that once-precocious child; it is who (this album says) she cannot help but be.

Too few people notice—except for the most hard-core of Swifties—how many first-rate songs she has written on topics apart from romance: tributes to family, capsule biographies, diss tracks, hymns to friends. And even Swifties often fail to notice the message that links so many of these songs to the ones about romantic love: chase a great love, if you like, even a heterosexual, cisgender love. Follow your romantic, erotic heart. But do not give up the rest of your life for love; do not hang your happiness or your future on a particular boy. Putting someone first (as Swift sang on “Bejeweled”) only works when you’re in their top five and you can do bigger things (as she sang on “Fifteen”) than dating the boy on the football team, even if that boy ends up with you. Staying home because your guy wants you there only works for so long, as in “So Long, London.” Chasing is thrilling until it isn’t, and then it is just lousy. With luck, you might find, as Swift apparently has, a guy who can take you and love you for who you are. But do not make that person your goal.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Swift tends to end her albums on an optimistic note. She could have ended this one with the fun, hope, and patience she found in “The Alchemy.” Instead, she closes disc one with “Clara Bow” and disc two with “The Manuscript,” a slow, pensive song about closure (“the story isn’t mine any more”). Before that comes “Robin” and before that “The Bolter,” a heady acoustic ode to the real-life socialite Idina Sackville, who earned that nickname by running away from five marriages. Each time “she just knows she must bolt,” she’s proving that she can still live her own life, a proof reinforced by cascading vowel rhymes: “It feels like the time / She fell through the ice / Then came out alive.” It’s a tribute to an independence from men—hot men, needy men, charismatic men— and it’s an almost gleeful apology for a claim that should require none: You do not have to do what your society expects. Swift’s stories of heartbreak are stories of resilience, too. They show her finding a way to survive even in the midst of everything. She can even do it with a broken heart.

Support independent journalism that exposes oligarchs and profiteers

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Concrete Poetics of Mary Ellen Solt The Concrete Poetics of Mary Ellen Solt

Her writing toed the line between fine art and poetry, asking readers to think of language as a multidimensional tool of communication and politics.

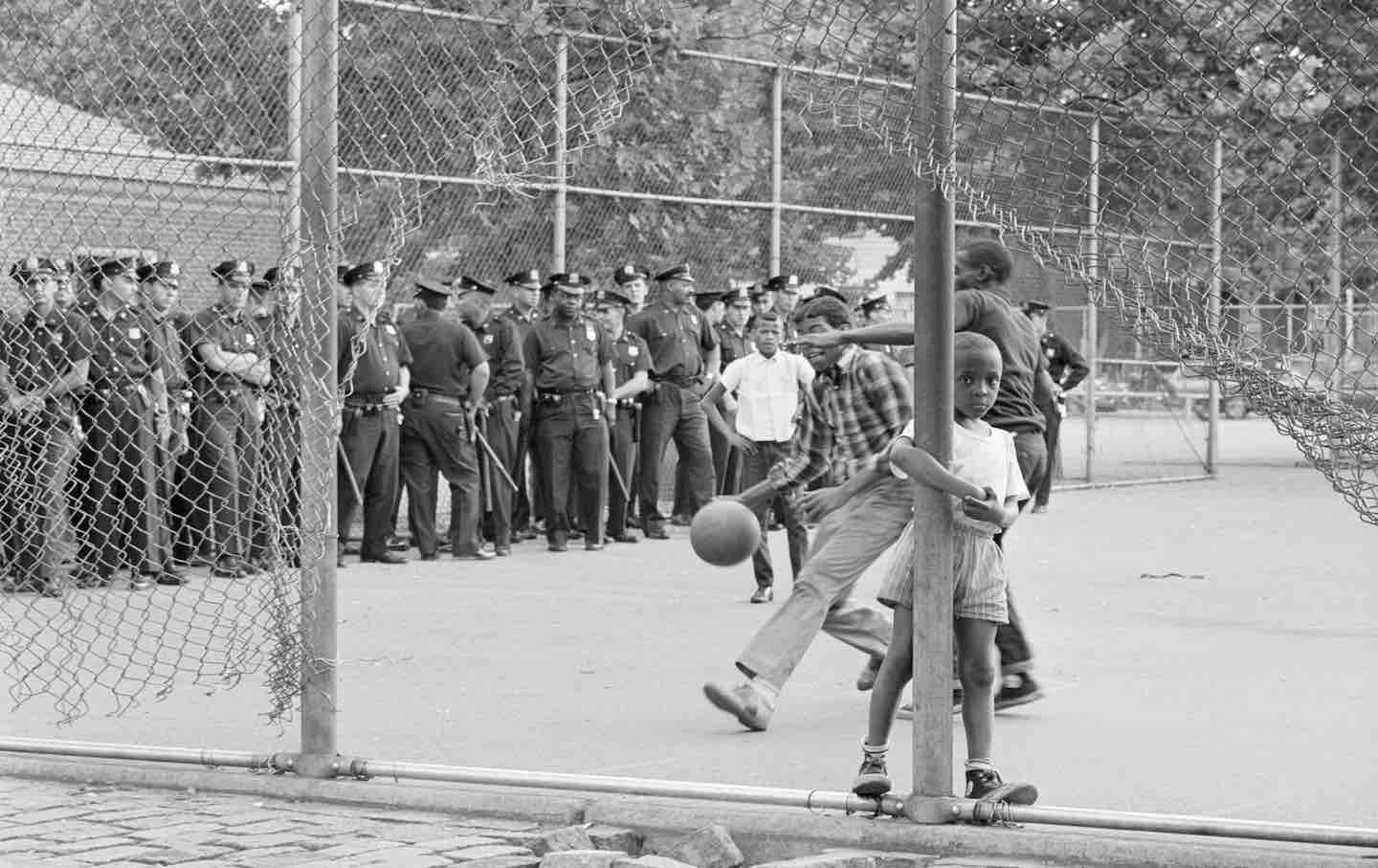

Brooklyn Dodger 1, Draft Dodger 0 Brooklyn Dodger 1, Draft Dodger 0

Donald Trump picked on the wrong athlete. Even though Jackie Robinson died in 1972, last week he bested Trump in a contest about the role of racism and the civil rights movement.

The Art of Separating: A Conversation With Haley Mlotek The Art of Separating: A Conversation With Haley Mlotek

The Nation spoke with the author No Fault, a genre-bending examination of marriage and divorce that is one-part cultural history and one-part memoir.

The Not-So-Golden Age of MAGA Troll Comedy The Not-So-Golden Age of MAGA Troll Comedy

In a blind rush to appease a phantom Trump demographic, media executives and billionaire owners are granting influential platforms to bigots, hacks, and panderers.

How White-Collar Criminals Plundered a Brooklyn Neighborhood How White-Collar Criminals Plundered a Brooklyn Neighborhood

Stacy Horn’s Killing Fields documents how East New York was ransacked by the real estate industry and abandoned by the city in the process.

When They Came for Columbia University When They Came for Columbia University

The university has become the Trump administration’s test case for the largest assault on higher education since the McCarthy era. Sadly, it has notably failed to defend itself.