Bayley fights IYO SKY for the WWE Women’s Championship during Night Two at Lincoln Financial Field on April 7, 2024, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

(Tim Nwachukwu / Getty Images)It was just after 3 am on a Saturday night in South Philadelphia, and I was watching an angry inflatable chicken fight a Japanese otter mascot in the middle of a hastily assembled wrestling ring. Around me, several hundred other spectators chanted, “Holy shit! Holy shit!”

I was two cheap whiskies deep and had become incredibly invested in the drama unfolding before me. As the moments ticked by, the chicken was vanquished, and the otter (not just any otter but Chiitan, a disgraced former mascot from the Japanese city of Susaki) faced off against a trio of fresh challengers—Double Unicorn Dark, Dr. Cube, and Silver Potato. During the fracas, Japanese women’s wrestling legend Aja Kong made a surprise appearance, drawing roars from the audience and briefly dominating the ring before her quick elimination.

My friend Hank—a lifelong wrestling fanatic with a two-and-a-half-foot-long rat tail and sweet Southern drawl—had smuggled me into Joey Janela’s Spring Break: Clusterfuck Forever, and the 87-competitor battle royal had more than lived up to its title. It was one of a litany of independent events timed to coincide with Wrestlemania 40, the biggest pro wrestling event of the year, which was being held in Philadelphia at the same time.

Some of tonight’s participants had already made it through half a dozen other independent matches throughout the city before taking their turn in the ring. Others, like Kong, were scheduled to appear at other events the next day. Wrestlemania itself sold out months ago, with 90,000 fans snapping up passes in record time, but the entire week had been flush with other indie wrestling events, from an all-Caribbean wrestlers matchup to a free punk show slash death match at a skatepark to an afternoon street wrestling block party on South Street.

As a confirmed night owl, I was delighted to find myself at this late-night shindig. It was light on production values but more than made up for it in grit, comedy, and sheer chaos. Most people were either sporting merch from their favorite wrestler or promotion or rocking their own spandex, leather, rhinestones, or otherwise festive duds. The overall atmosphere was deeply familiar; with a few programmatic tweaks (and a much better sound system), it may as well have been a heavy metal festival.

That wasn’t the only similarity. When I asked Hank about the financial particulars of these kinds of shows, especially for foreign wrestlers who have to factor in extra travel and visa costs, he laid it out in a parallel that any touring underground punk and metal band would recognize: They do it because they love it, not because they expect it to pay off someday. It’s about art, not glory.

Of course, some pro wrestlers do make it big, but signing a contract with a corporate behemoth like WWE doesn’t guarantee fame and fortune. Even the biggest names work as independent contractors and find themselves perpetually subject to the whims of their employers. Professional wrestling’s entire economic model hinges on worker exploitation, and a championship belt can end up as a golden millstone around a performer’s neck. As Dan O’Sullivan wrote for Jacobin, “Pro wrestlers have been largely unable to bargain for their compensation or type of work; with no guaranteed income, of the sort generated by an equitable contract or official employment, most wrestlers have been happy to take what they can get.”

Efforts to unionize the industry have failed, over and over again. In 1986, Hulk Hogan thwarted a union drive led by Jesse “The Body” Ventura by ratting out his coworkers to the boss. “Hogan made more money than all of us combined,” Ventura told Steve Austin in 2016. “So naturally, he didn’t want a union.” Ventura, himself a member of the Screen Actors Guild, has long spoken out about how the independent contractor model hurts wrestlers, and that parallel reaches far beyond the music and entertainment worlds and into the gig economy. Pro wrestlers are workers, and most of them are getting screwed over.

In a bittersweet moment, I realized we were just a few blocks up from the Sheet Metal Workers union hall. Union labor had built the hall we occupied, yet the workers performing in the ring that night were wholly on their own. Other professional athletes are represented by their own powerful unions, and benefit mightily from that collective power. Meanwhile, their bedazzled counterparts in this fundamentally working-class sport are left out in the cold, abandoned by labor laws, and exploited by greedy big-wig promoters. That’s probably why the pro wrestling community is so tightly knit—it really is them against the world.

As the Clusterfuck unfolded, I watched in awe as the wrestlers practiced their art in front of a cheering crowd. I saw a 398-lb Beastman hurl himself off the top rope and fly through the air with the greatest of ease. Pollo Del Mar, a beloved local drag queen, lost her wig but not her glamor. An inflatable sex doll named Yoshiko triumphed over multiple humans. World Famous CB, aka Cheeseburger, a charismatic local favorite who runs a well-respected wrestling school, chased a gleefully naked man around the ring. Edith Surreal, who trained with CB and credits wrestling with giving her the confidence she needed to transition, came out to an especially loud roar. A man dressed as an accountant, tight blue Dockers and all, represented New Jersey alongside a mountain of a man named (of course) Big Vin. Japanese phenom Rina Yamashita, whipping her braids in a hurricane halo, coolly decimated all comers as the crowd sang out, “Rina’s gonna kill you! Rina’s gonna kill you!”

Modern pro wrestling branches off from vaudeville, loops back through the circus, launches off a theater balcony, and takes a detour past Muscle Beach before hammering together a space all its own. It’s held onto its malleability and perennial status as a home for misfits and weirdos who don’t quite fit in anywhere else. As an accessible working-class art form, it’s become a magnet for generations of performers who came into wrestling with little more than a dream and a high pain threshold. It’s not a coincidence that pro wrestling is one of the few theatrical arts in which a performer can still succeed wholly on their own merits. You don’t need rich parents or a degree from a prestigious institution to don the tights and become a star; it’ll still cost you and the view from backstage isn’t always pretty, but the barrier to entry is far lower. How do you get to Wrestlemania? Practice.

Despite all of that, pro wrestling still doesn’t get the kind of respect it deserves as a unique global art form. Wrestling is a demonstration of physical skill, but it is so much more than that, too (without even getting into bloody death match–style violence).

Yes, it can be silly, and cringey, and problematic. Racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and xenophobia are far from things of the past; for example, just last year, former WWE writer Britney Abrahams sued the company over its discriminatory storylines. The world of independent wrestling is not without its problems either, but things are changing. I can say that the broad diversity of both the performers and the audience at the Clusterfuck was a joy to behold, and made the event a hundred times better than if it had merely been an endless parade of hulking peach-colored men with bulging muscles.

Besides, can any artistic medium claim to be free of such flaws? Wrestling may be an interactive theater of the absurd, but its stories are Shakespearean in their vast span of emotional textures—love stories, revenge stories, comedy, tragedy, raunchiness and ribaldry and plenty of gender-bending, family feuds, and illicit affairs. What is kayfabe if not an inverted Greek chorus, in which the audience obscures its true knowledge of the tale’s complexities?

The storylines are ancient. A favored artist marries his patron’s daughter, winning himself a place among the aristocracy; a young woman’s talents are downplayed or ignored until she seizes power for herself; countless young men brutalize their bodies for a chance at reward and redemption, only to fall apart after the fog of war clears. When God sings with his creations, will a heel not be part of the choir?

To sneer that wrestling is “fake” is to sneer at the theater itself; lest we forget, every play has a storyline and an ending, and every Hamlet dies. At least in wrestling, there’s the whisper of anticipation that someone might get hit over the head with a steel chair at some point. It is a proletarian theater, in which everyone in the metaphorical cheap seats is welcomed down into the front row and encouraged to get as rowdy as they deem necessary. The players shine with sweat, holding their belts aloft like the gods of Olympus. The spectacle is the point. You—yes, you—are welcome here, exactly as you are. Hell yeah, brother.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Though I am a novice in the ways of pro wrestling, I do know a little bit about the social space it occupies. I grew up in a NASCAR family. My dad makes moonshine and my cousin drag races out in the woods somewhere. A Juggalo took me to prom. I love monster truck rallies and heavy metal and swimming in abandoned quarries. I would sooner swear at my grandma than go to a literary salon.

Those are all perfectly reasonable preferences to hold, and yet there is an unspoken negative valuation to them. Low culture—popular culture whose mass appeal speaks predominantly to the poor and working class—has come a good way down the long road to the mainstream, but that won’t stop some folks from judging you for partaking in its charms. Its products are enjoyed by working-class people from a variety of backgrounds who have enough time and resources to invest in their respective passions. There is inherent artistic value to these cultural artifacts and social practices, and they require a high level of dedication, talent, and skill from their creators.

Yet to openly acknowledge these facts opens one up to criticism from those who have saddled themselves with exclusively “highbrow” and “elite” tastes. I refuse to entertain the notion that pro wrestling fans are any less discerning than anyone else when some of the dumbest motherfuckers alive hold political office and write opinion columns for The New York Times. There’s nothing wrong with genuinely enjoying art museums, opera, and The New Yorker, but using that as an excuse to look down upon someone else who’d rather spend a few evenings of their one wild life chugging a few beers and cheering for their favorite babyface is a real dick move. (Or, to phrase it slightly more elegantly, that strain of close-minded, priggish pomposity so endemic within the chattering class has seldom endeared them to many outside of its self-consciously rumpled circles).

The most moving five and a half minutes of the entire Clusterfuck came near the middle, when nobody was wrestling at all. Throughout the evening, each wrestler had come out to their own theme music and been greeted warmly by the crowd. But when Wheatus’s mega-one-hit “Teenage Dirtbag” began playing around 2 am in the midst of a several-man melee, everyone simultaneously lost their collective shit.

As wrestlers danced and clapped alongside their fans, Spyder Nate Webb, resplendent in a bandana and denim patch vest, strutted out. Arms held high like a conductor’s baton, he led the crowd in song as Philly Mike, anxious to begin, looked on from inside the ring; it was clear that the only action anyone was interested in at that moment was nailing the quiet part. It was a spine-tingling moment of shared humanity, of recognition and sheer delight at being in that specific room with those specific people at that specific moment in time. For a few golden minutes, we were all dirtbags, together. As the song reached its crescendo and faded out, Nick took a bow—then out from the crowd came a Delco-inflected cry, “Play it again! Play it again!”

The chant built up speed and the wrestlers looked around, powerless to resist the people’s voice. As an exasperated Philly Mike sank to his spandexed knees, the opening chords of “Teenage Dirtbag” rattled through the speakers once more—then stopped. Philly being Philly, the crowd then turned en masse and began booing the DJ. It worked. That night, Broad Street bullied its way to nirvana, and Wheatus rode again. This time, the crowd sang even harder. An airhorn kept time. The walls shook as we moved as one animal to belt out the immortal chorus. It was electric. It was everything. It was pro wrestling, and it was ours.

More from The Nation

The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…” The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…”

In his celebrated mea culpa, the German pastor Martin Niemöller blamed his failure to speak out against the Nazis on indifference. Was that the whole reason?

“The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy “The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy

The new show from the creators of The Office reminds us that their comedic style does now work in every “workplace in the world.”

John Updike, Letter Writer John Updike, Letter Writer

A brilliant prose stylist, confident, amiable, and wonderfully lucid when talking about other people’s problems, Updike rarely confessed or confronted his own.

The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme” The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme”

Josh Safdie’s first solo effort, an antic sports movie, revels in a darker side of the American dream.

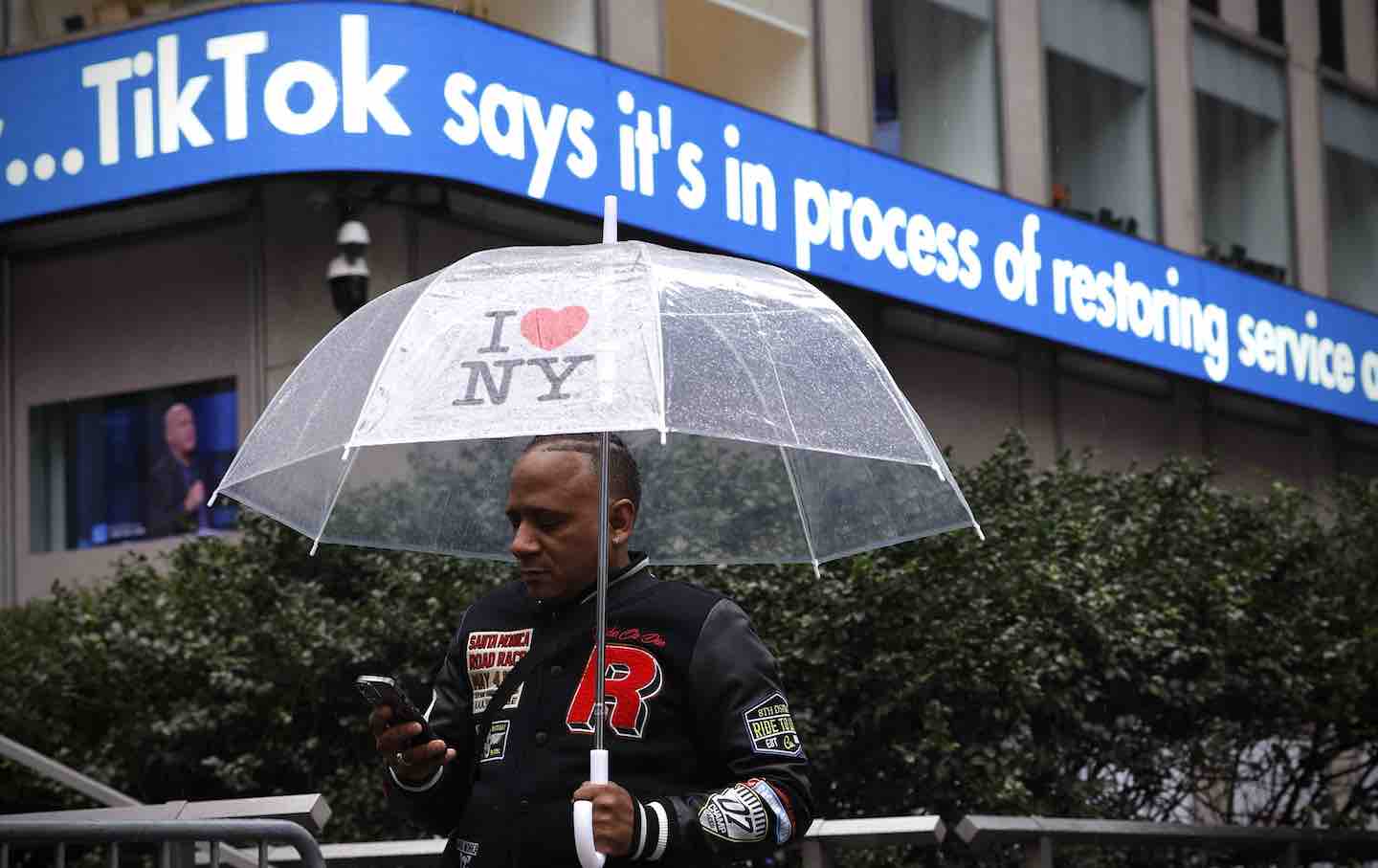

TikTok’s Incomplete Story TikTok’s Incomplete Story

The company has transformed the very nature of social media, and in the process it has mutated as well—from tech unicorn to geopolitical chesspiece.