The Haunting of the Publishing House

The racism and prejudice of the industry has been the subject of recent novels. In R.F. Kuang’s Yellowface, that plot becomes a horror story.

In January 1971, Publishers Weekly asked its readers—for the first time, but certainly not the last—a provocative question: “Publishing: A Racist Club?” Bradford Chambers, the director of the Council on Interracial Books for Children, wrote the piece in response to two high-profile awards controversies. Four years prior, in 1967, William Styron’s Confessions of Nat Turner won the Pulitzer Prize, despite staunch criticism from many Black writers. Three years later, William H. Armstrong’s Sounder, a young adult novel about a boy, his dog, his imprisoned father, and their sharecropping family, won the Newbery Medal, even though it was, like Confessions, written by a white man and roundly criticized for perpetuating offensive caricatures of Black life. As Chambers wrote in Publishers Weekly, “If we give our highest awards to books that try to delineate the minority experience yet, upon further re-examination, turn out to be inherently racist, what does this say about the publishing industry?” This question would be asked countless times over the next 50 years.

Books in review

Yellowface

Buy this bookChambers details the creation of the Office of Minority Manpower in 1969—by his estimation, the first “industry-wide effort to recruit minority talent.” Among the initiatives that the group pursued, but ultimately abandoned due to a lack of funds and interest, was a coordinated financial investment in Black-owned bookstores, the creation of new imprints to produce books by and about people of color, and high-profile editorial hires to staff them. Chambers asked, “Do these steps add up to a commitment, to a sincere desire to change the structure of publishing? Or are they tokenism only?” By 1971, the Office of Minority Manpower had already fizzled, receiving no support from the publishing executives who once championed its creation, leading Chambers to conclude that the “industry has acted mainly to counter publicity adverse to its image.”

With only a few small changes—a name here, a euphemism there—the article could have been one of many that ran in the last few years, examining the publishing industry’s response to George Floyd’s murder and the national uprisings it triggered. The pattern was recognizable: a recommitment to DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion); committees formed and promises made; staff hired, “books about race” acquired. The initial enthusiastic commitment was followed up by a lack of support, amounting to no lasting structural change.

Yet, recently, instead of simply forming a task force or two to appease detractors, publishers have opted not to counter the negative publicity or bad image; instead, they have published books about their misdeeds, recasting the industry not as beleaguered protagonist but as racist antihero: The Other Black Girl, by Zakiya Delila Harris, and Luster, by Raven Leilani, are two prominent examples. The latest entrant into this genre of institutional critique, Yellowface by R.F. Kuang, offers a scathing portrayal, satirizing the publishing industry’s fetishization of racial identity and skewering its so-called commitment to diversity.

The book’s narrator, June Hayward, is an insecure and unsuccessful novelist who published a flop of a debut and is struggling with writer’s block. Athena, her friend, is everything June is not: an MFA from “the one writer’s workshop everyone has heard of,” a successful first-time novelist published by a Big Five imprint, feted and celebrated. After Athena dies in a freak accident, June steals her manuscript and passes it off as her own. June is white; Athena was Chinese American and wrote a sweeping historical epic about the experience of the Chinese Labor Corps in World War I. June cynically cultivates her “ethnic ambiguity” and publishes to great acclaim—and, later, significant backlash when her theft is discovered. Her attempts to explain and justify herself only make matters worse; she is subject to not one, not two, but multiple cancellations.

As a satire, Yellowface is fine. It makes its point, if rather didactically. June is less an “unreliable” narrator than she is a very confused and defensive one, eager to explain herself and justify her (maybe-probably-racist-but-not-on-purpose) actions. The situations that Kuang dramatizes have all been too well-documented to be particularly shocking. Seen in this light, Yellowface might be better seen as a ghost story—an allegory for an industry haunted by its misdeeds.

In the gothic tradition, the ghost story is a sort of morality tale, populated by characters who double as walking metaphors and set in a foreboding landscape that reflects internal, psychological, or social problems. The ghost is a physical embodiment of an unresolved past, like the imposing, crumbling architecture after which the literary movement was named. Though Kuang swaps the castle for the publishing house and the misty moors for Twitter, Yellowface is no less moralistic in its exploration of the problem of racism in publishing, its characters no less cardboard. Yet even a searing critique of publishing can’t avoid being caught up in—and even benefiting from—the system it sets out to skewer. More publicity, however negative, won’t fix what is ailing the industry.

Kuang’s meticulous world-building, honed over a career as a writer of fantasy novels, is put to good use in Yellowface, rendering a publishing industry full of opaque politics and elaborate customs. It is filled with jargon that quickly divides the insiders from the outsiders: ARCs and WIPs, Kirkus and Goodreads, Book Riot and LARB. In this way, Yellowface pays respect to the industry that produced it, enfolding its primary audience—book people—into the narrative. Its juicy story of online cancellation aside, the novel may strike outsiders as self-involved, its sense of the industry’s significance overinflated and, frankly, kind of silly. But novels for and by book people can rely on enthusiastic support from publishers (book people), interest from the critical community (book people), and a base of avid readers (also, book people). The novel’s self-involvement is its chief selling point.

Yet, unlike the bookish novels that have arisen in other commercial genres—Emily Henry’s romances, for example—Yellowface does not entertain a rosy vision of publishing. Rather, Kuang presents an industry not entirely different from the one that Chambers described in 1971. As soon as June submits the manuscript that she stole from Athena as her own, she encounters an industry with whiteness at its very center. The entire editorial staff of her fictional publisher, Eden Press, is white, save for one lowly assistant who is quickly sidelined when she suggests hiring a sensitivity reader for the novel. This is hardly satire; according to the most recent Diversity Baseline Survey, conducted in 2019 by Lee & Low, an independent publisher of multicultural children’s literature, 76 percent of industry professionals self-identify as white, 85 percent in editorial. Instead of hiring and mentoring more people of color, publishers call on (freelance, precarious, expendable) readers from minority communities to do due diligence, ensuring their white writers aren’t being overtly racist but rather “sensitive” in their fictional renderings of people of color.

June rejects the very idea of a sensitivity read as preposterous, claiming that she has done her own careful research. The rest of the Eden editorial team isn’t terribly concerned; they presume the novel’s reading audience will also be white. Again, this is not exactly satire, but a well-documented phenomenon: Researchers in the UK have found this to be a common assumption among editors. And so white editors edit the manuscript with these white readers in mind. June is told that the “original draft is unbearably sanctimonious” and that it may alienate her target audience: book clubs. June “soften[s] the language,” making her white characters less “cartoonishly racist,” more open-minded toward the Chinese laborers; at least one Chinese character is rewritten as a white ally. And the editors also prevail on her to change the ending. Instead of reflecting on anti-Asian racism, the book, titled The Last Front, now ends on a hopeful note. The result: “a universally relatable story, a story that anyone can see themselves in.” But not any anyone, of course. June knows that the book club audience, that most sought-after commercial reading bloc, is composed of “largely Republican white women.”

The Last Front, then, is like countless novels that purportedly address themes of racial inequality and inclusion, yet are designed to appeal exclusively to the political and economic sensibilities of white, upper-middle-class readers. There are the obvious commercial examples, of course: The Help, American Dirt. But even June’s description of The Last Front (at least as Athena initially wrote it) sounds a good deal like the sort of novels that have been increasingly awarded the nation’s top literary prizes: historical fiction, written by a person of color, that exhumes a forgotten, if traumatic, racial or ethnic past. The sort of novel that, before writing one of his own, Colson Whitehead satirized as “the Southern novel of Black misery.” The sort of novel that Edie (of Raven Leilani’s Luster) finds on the “Diversity Giveaway” table at her publishing house: “a slave narrative about a runaway’s friendship with the white schoolteacher…and a book about a Cantonese restaurant, which may or may not have been written by a white lady in Utah, whose descriptions of her characters rely primarily on rice-based foods.” The sort of novel that Percival Everett’s Thelonious “Monk” Ellison writes as a hoax in Erasure, only to find it winning the (fictionalized) National Book Award.

There is, of course, a literal ghost that haunts these pages as well. From the moment she steals Athena’s manuscript, June is consumed with a guilt that only intensifies as she becomes the target of social media ire. Then she begins to see the ghost of Athena everywhere: at a reading, in a coffee shop window, and walking down the street. Athena’s ghost appears in coordinated social media accounts and in death threats and hateful messages online. Athena is the problem that won’t go away. Every time June thinks that she has made penance for her misdeeds—donating to a scholarship fund for AAPI writers, speaking to an Asian American book club—Athena returns, reminding June of her original sin.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Like Athena’s ghost, June finds that the scandal that surrounds her simply will not die. Neither will her book’s sales. Though she prepares for her publisher to drop her and for the invitations to cease, the opposite happens: June has become a cause célèbre among right-wing commentators hungry for a culture war. “Probably not people you really want to associate with,” her agent admits. But June’s sales nearly double. “At the end of the day all that really matters is cash flow,” her agent says. Her publisher may perform its embarrassment, may issue statements of apology or launch an in-house listening tour, but it certainly will not yank her book: “You’re pulling in too much money for them to back out now.” June shifts from being the beneficiary of the much–celebrated “push to diversify” the publishing industry after 2020, to a hero of the cynical backlash. (Or as The New York Times detailed this phenomena, “In Backlash to Racial Reckoning, Conservative Publishers See Gold.”) Race is a lucrative commodity, whether in the form of anti-racist historical narratives or hate-filled, right-wing vitriol. In publishing, even the problem becomes profitable.

Like much else in Yellowface, this critique is delivered rather heavy-handedly, with June’s agent and editor performing the literary equivalent of dastardly mustache-twirling. Yet Athena’s ghost is, perhaps unintentionally, the most damning criticism of an industry that has long been aware of its mistreatment of people of color but has yet to make the structural changes necessary to create an equitable working—or reading—environment. Just as June is haunted by Athena, so too have these critiques of publishing returned periodically, jarring the industry into momentary action before fading away. Fifty years after Bradford Chambers asked the question, we are still haunted by it: “Is the publishing industry a racist club?”

Chambers was not the first writer to call the publishing industry racist. He was simply the first to do so in Publishers Weekly, the leading trade magazine for an overwhelmingly white industry. Writers of color had long been making this critique, which was ignored by the white power brokers. In 1950, for instance, Zora Neale Hurston published “What White Publishers Won’t Print.” Hurston, unlike Kuang and others, looks upstream to identify the source of the racism she encounters. She allows that “various publishers and producers” are “edging forward a little” in their willingness to publish work by and about Black people, but they are not activists; they are in business, and they feel that these books will not sell: “Public lack of interest is the nut of the matter.” In 2022, Hurston’s essay was republished in Lit Hub to announce the release of a book of her essays; in 1950, it was initially published in Negro Digest, a magazine unlikely to have been read by the subjects of her critique, those publishers controlling commercial interests. As the title of the essay claims, it certainly would never have been published by them.

So how did a book like Yellowface, which pulls no punches, get published by a Big Five imprint? This question has been lingering in the minds of many who have read the novel, including those who worked on it. The New York Times recently published a story, “R.F. Kuang Wrote a Blistering Satire About Publishing. And Publishing Loves It,” that detailed both the reluctance and the enthusiasm the book generated behind the scenes. “There are things in here that I am afraid could offend people you work with,” Kuang’s agent, Hannah Bowman, reportedly told her before submitting the manuscript. Kuang’s editor at William Morrow, May Chen, shared this concern, describing her reaction as: “Oh my God, she’s writing this takedown of publishing, is it going to be a problem for Harper?” Evidently, it has not been a problem. Yellowface enjoyed a fate similar to the fictional The Last Front: It is a bestseller. Amazon Books installed a giant billboard outside of Penn Station. And despite its light mockery of book clubs and their members, Yellowface was selected as the July pick for Reese’s Book Club.

As Yellowface so painstakingly details, literary successes do not simply happen spontaneously; they are the result of the labor of countless hours and countless hands—and not a small amount of luck. In other words, Yellowface’s critique was not merely tolerated by the publishing industry but embraced enthusiastically and promoted energetically—not unlike The Other Black Girl before it. “Doesn’t it scan as odd,” Tajja Isen asked about The Other Black Girl in 2021, “that the collective book industry reply to ‘your working conditions are so racist they’re a form of psychological horror’ was an ecstatic yes, drag me?” Are these novels demonstrations of atonement, or mere theatrical self-flagellation?

As June continues to unravel, the extent of her plagiarism now uncovered, she begins to consider her redemption: autofiction. “I won’t dodge the controversy anymore,” she vows. “That mindset has been holding me back—until now.” June will write about watching her friend die, about stealing her manuscript; she will control the narrative. She will venture into the heady world of critical theory, asking probing questions about creativity and originality and the death of the author—catnip for academics, she speculates, imagining the studies they will write about her. “And once this scandal has been transformed and preserved in novel form, once all the ugly, unconfirmed rumors about me have been relegated safely to the realm of fiction, I’ll be free.” June incorporates even the harshest critiques directed at her into this new project, thereby neutralizing them. Not absolution, then, but aestheticization and, with it, critical distance.

The publication of books like Yellowface, The Other Black Girl, and the similar novels that will certainly follow is not an admission of culpability or genuine evidence of change. Celebrated and promoted, Kuang’s critique can’t hurt anymore. Its success only underscores this irony: Publishing will capitalize on racial identity and overt racism—including its own—when it is profitable. This is racial capitalism at work: a structure of extraction, in which maximum economic and social value is derived from racial identity.

In the end, June’s haunting turns on her own racism as much as her guilt or creative faculties (and excuses): When she finally confronts the ghost, she finds not Athena but another Asian American writer. The implication is clear, even before the non-ghost spells it out for us: June cannot tell one Asian face from another. Athena will, undoubtedly, return to continue haunting June. Again, and again, and again.

The publishing industry, likewise, will continue its cycle of recommitment and neglect—again, and again, and again. There will be more articles resembling those written in 2021, just as they, in turn, resembled the articles written in 1971. But instead of shunting these critiques, like Hurston’s, off to the side, the industry will reward them with pride of place in catalogs, book tours, online promotions, billboards, and spots on the bestseller list. Like June, publishing has learned to live with its ghosts.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks Rob Reiner’s Legacy Can't Be Sullied by Trump’s Shameful Attacks

The late actor and director leaves behind a roster of classic films—and a much safer and juster California.

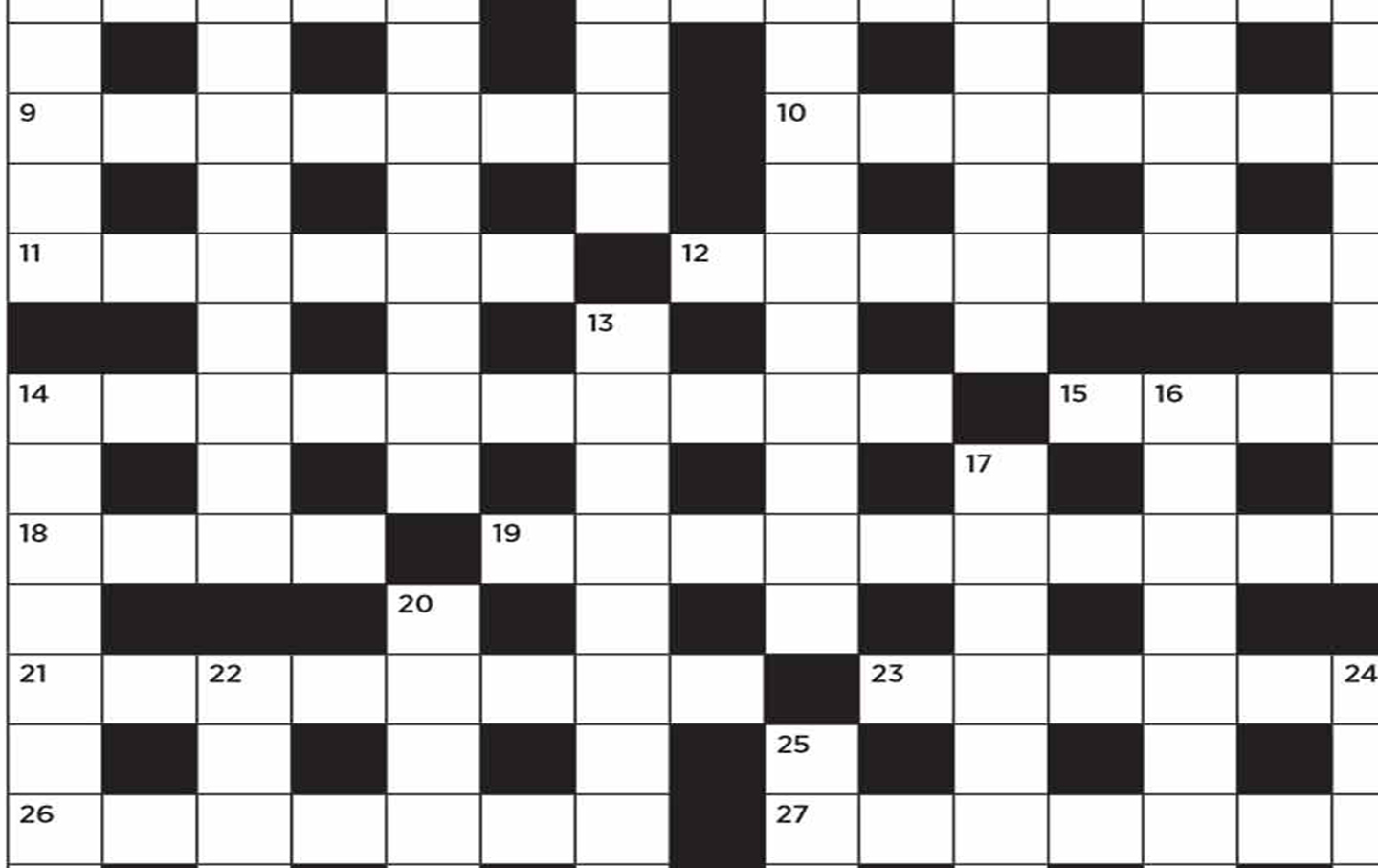

Solution to the “Big Event” Crossword Solution to the “Big Event” Crossword

If questions remain after reading this, please write to sandy @ thenation.com.

Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments Blood Orange’s Sonic Experiments

Dev Hynes moves between grief and joy in Essex Honey, his most personal album yet.