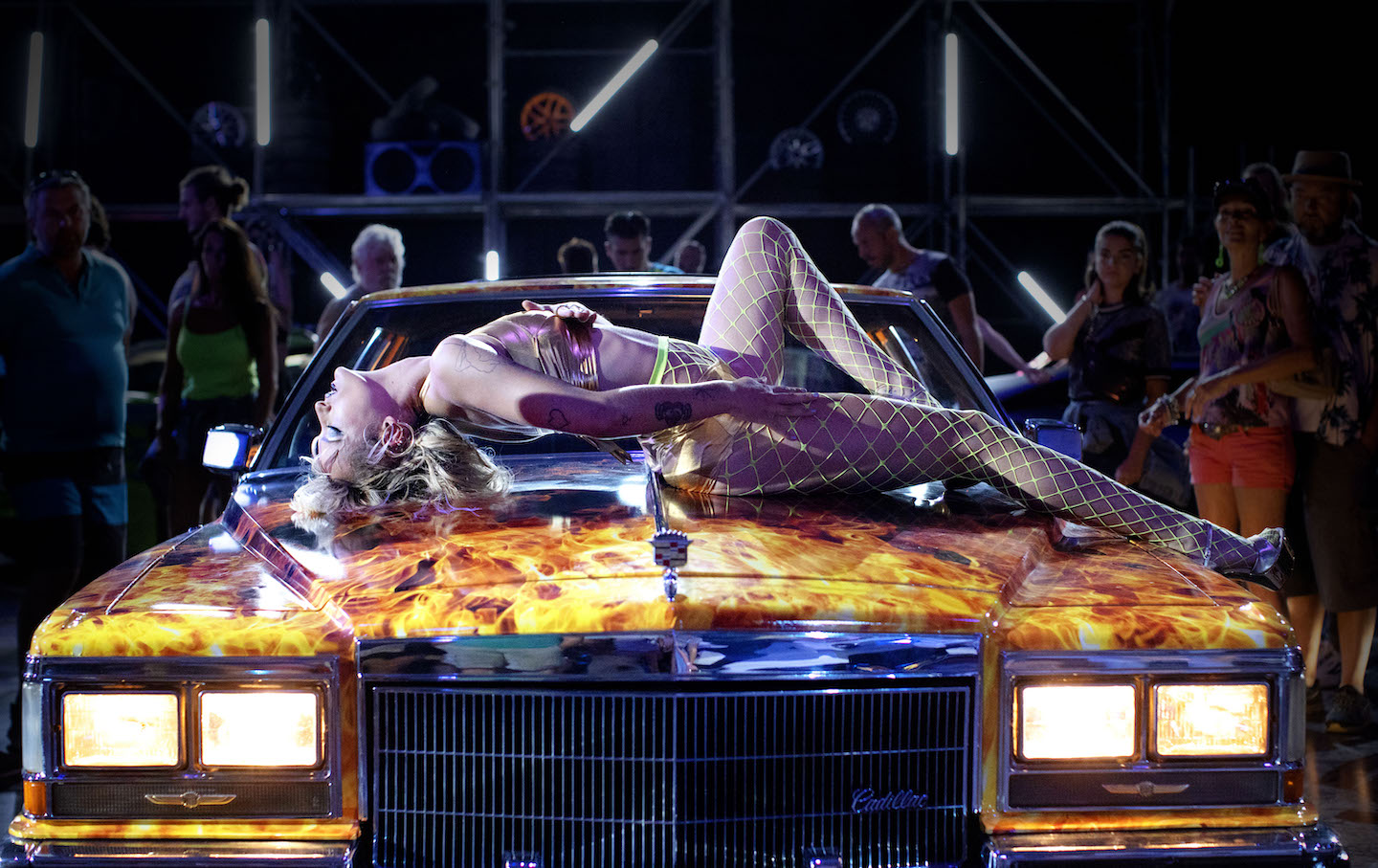

Agathe Rousselle in Titane.(Photo by Carole Bethuel)

Before you could slip the world in your pocket and conjure its sleek apparitions with a thumb on glass, David Cronenberg’s 1983 film Videodrome envisioned the body’s encounter with technology as a grotesque collision: cassette tapes plunged into a yonic gash where the stomach should be; a firearm made literal as mottled flesh grows over a gun, claiming its contours like moss would a stone. Such fears of technological corruption well predate Videodrome, but the film’s ragged suturing of human and machine centers a long-standing anxiety about the body and its boundaries: where it begins, where it ends, and how much of its wants and needs are really its own. These are also the stakes of Julia Ducournau’s Palme d’Or–winning Titane, a film teeming with the kind of carnal metamorphoses that Cronenberg once called “the flesh undergoing revolution.” Bodies leak, tear, and erupt, but in Titane, the flesh’s revolt begins long before the bursting viscera. In the very first scene, an accident inflicts a wound so indelible that the rest of the film leaves us to wonder if there can be a life—or a self—forged apart from its deepest traumas.

We open with close-ups on the inky black innards of a car in motion, its metallic frame glossed with condensation and motor oil, evoking a wet and quivering sentience of its own. In the back seat is our protagonist Alexia as a child, forestalling boredom by mimicking the car’s loud engine, her voice synced in a whirring crescendo. In a split-second tragedy, there is a crash, a bloodied thud, and a frantic cut to an operating table, where a titanium plate is hammered into Alexia’s broken skull. The doctors warn her parents to watch for signs of neurological dysfunction, but comfort them with the promise of stability: Unless there’s a violent impact, the plate will not move. Newly discharged, Alexia approaches a car not with trepidation but sensual fascination, stroking its steel curvature as if the titanium that cups her brain has taken the memory of pain and rewritten it as pleasure. Brief, as prologues are, but this scene is enough to cast the strange alloy of bodily trauma and prosthetic tech as the possible coauthors of a new life, their autograph the deep scar etched into the bald crescent above Alexia’s right ear.

The film promptly cuts to a thirtysomething Alexia (Agathe Rousselle), now a dancer at a car show where she’s but one gyrating attraction in a pageant of fishnets and lamé spandex. Men flock to her sinuous routine, but when a fan assaults her in an empty parking lot after the show, she stabs him in the ear with a metal hairpin. As it turns out, it’s both a defensive reflex and a psychopathic habit—Alexia is a serial killer whose signature flourish is a blunt-force puncture wound. Another habit: She has a sexual preference for cars, and winds up pregnant with the mystery spawn of a flame-lapped Cadillac. After a would-be victim flees by shoving her head into a wall—causing a second bloodied thud—Alexia’s face shows up on wanted posters and the evening news. As her physique bolts through trimesters at light speed, she chances on a missing-persons notice bearing the digitally aged likeness of Adrien Legrand, a boy who vanished some 20 years ago. Alexia slips into hiding disguised as Adrien, the long-lost son of an aging fire chief, Vincent, whose body, too, is straining against time.

Vincent is played by veteran actor Vincent Lindon, whose new shroud of unexpected brawn introduces the curious tempo of an offscreen bodily transformation. It took two years to build this new physique: “Everything is more complicated when you’re 62,” Lindon told an interviewer at Cannes. “The skin is not the same.” Alongside newcomer Rousselle’s mostly mute performance (and whose preexisting tattoos invoke another challenge to interpretation), Lindon’s storied presence confers a familiarity that makes Vincent seem easier to read. His body is tense with years of towing wreckage from infernos and injecting steroids, but loneliness softens him, leaving its trace in Lindon’s downcast eyes. Vincent’s life, like Alexia’s, has grown around a loss that still holds its shape: Here is someone who needs to be needed, whose sense of self has collapsed without fatherhood and family. This is the rhythm of Titane’s central duet—two bodies tested by pain and grief, first drawn to each other by chance, then kept together by the gravity of their mutual transformations.

If the spate of technophilic (and -phobic) genre films after Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979)—body horror sci-fi, tech noir, cyberpunk—have tended to stage this thing called “technology” as some formidable antagonist to organic life, Ducournau returns us to a much older conception in the Greek term tekhnē, which broadly encompasses a notion of technique, craft, or skill. Titane is filled with the kind of sci-fi visuals that cue a reading of technology as an intrusive force, but I suspect the film is more concerned with technology as a mode of creation, recalling the philosopher Bernard Stiegler’s idea that our tools and gadgets are not just extensions of the human sensorium but the sum of all the doing, using, and inventing that makes us human.

Alexia, after all, has procreated with an automobile, though the scene of their copulating is cryptic enough to raise the possibility of self-delusion: Its headlights beaming in a vision both comical and divine, the Cadillac draws her out of a shower, naked and wet, as if dripping in amniotic fluid. There’s something funny in the proximity of “self” to “auto,” which reminds me of the winking nomenclature imposed on car-crash fetishists in Cronenberg’s Crash (and J.G. Ballard’s source novel): autophiles.

But the spectacle of Titane’s vehicular erotica is a red herring. Cars are far less interesting in the context of sexual deviance than in their role as agents of somatic change, responsible for one of the two transformations that wrack Rousselle’s wiry frame. Each pulls her body toward a future on the other end of an obvious gender binary: While her breasts and crotch leak black motor oil in lieu of the usual fluids, she also shears her platinum shag, binds her chest with a medical bandage, and resolutely breaks her nose on the edge of a sink, cramming herself into an Adrien-shaped form just convincing enough for a lonely father to suspend disbelief. When a police officer asks Vincent if he’d like a DNA test done just to be sure, he scoffs: How would he fail to recognize his own son? In tense nocturnal silence, he drives this changeling home and sets her up in the shrine that is Adrien’s untouched room. Alexia strips and collapses, visibly pregnant, on this ghostly boy’s bed, as though tossed into a stranger’s childhood memory. There is an uncanny distortion of time in this image, as though a host of possible futures have erupted in the space of a single life—and body.

Titane’s most obvious conceit is its refusal of tidy binaries—between genders, between human and machine—distilled in the image of Alexia/Adrien’s corporeal form, her ready-made father figure, and her hybrid offspring. As an explicit metaphor, this conceit can feel compelling but overdetermined, almost too obviously signaled on the literal surface of the characters’ bodies: the web of red striations on Alexia’s skin, where her bandage’s horizontal lacerations run contra the vertical stretch marks of her blooming stomach; Vincent’s vicissitudes in the constellation of needle bruises that fleck his ass, and the texture of his aging skin. What is the sum of these inscriptions and all the other changes on a body’s terrain? The easy reading of Titane has an answer to this, offered as some affirmation of identity against the essentialism of biology, but Ducournau has built in far more questions than she can address. Lost in the neon-lit bedlam of Titane’s body horror is the film’s exhilarating sense of a life that could have been otherwise: a childhood—or a body, or a vehicle careening down a highway—that could have taken a soft turn instead of a hard one.

But there’s no real way to check if different turns would have led to different selves, if a violent impact to the head caused a neural misfire or corrected one. This reiteration of the nature-or-nurture cliché is a possible through-line between Titane and Ducournau’s debut feature, Raw (2015), in which a young girl’s cannibalistic impulses are, in the final scene, revealed to be hereditary. There, it seemed to me a grating gesture of containment in a film otherwise delighting in excess, but Ducournau returns to the problems of self-formation in Titane, now coiled into a knot of trauma and identity. Where is it that perversions, sexual or otherwise, take root? Maybe in the intimate sphere of the private family unit, maybe in the threads of a chromosome before there is even a body. After the prologue, there is no return to Alexia’s childhood, nor any attempt to chart the evolution of her desires and compulsions. Nothing, in short, to fuel that beloved metric of critical appraisal in narrative cinema: characterization that is backed by nuanced but legible motions of cause and effect.

Against the seductive propulsion of Titane’s plot, these omissions seem like a facile default to ambiguity. So we search for and pinpoint the moments that should explain who and why, and bristle when they don’t quite work. But this is what Titane resists, despite the sacral bent of its finale: the tempting fiction that pain and loss can always be spun into revelation, that the lucid arrangement of events in a life will always lead to a cohesive self. Maybe suffering and its traces are just incoherent, like the old scar that curls above a woman’s right ear, carved as if a hieroglyph, its meaning lost to flesh and time.

Phoebe ChenTwitterPhoebe Chen is a writer and PhD candidate living in New York.